Key Points

- There is disagreement and discussion about the definition of spirituality

- Ageing is a journey which includes a spiritual dimension

- The spiritual dimension focuses on meaning of life, hope and purpose, explored through relationships with others, with the natural world and with the transcendent

- The evidence base suggests that genuine and intentional accompaniment of people on their ageing journey; giving time, presence and listening are the core of good spiritual practice

- Reminiscence, life story, creative activities and meaningful rituals all help the process of coming to terms with ageing and change

Introduction

It is predicted that by 2033 there will be a 50% increase in the number of people over 60 in Scotland. This is accompanied by increasing longevity. Living longer brings with it possibilities of enhanced health, happiness and productivity but also increasing frailty, chronic illness and diseases of older age such as dementias, diabetes and heart disease. Scottish health and social care services spend more time and money on this sector of the population than any other (Scottish Government, 2010a). Social and health care policy documents specify person-centred compassionate and dignified care (NHS Education for Scotland, 2011), yet, examples of poor care of older people continue to emerge. Focusing on the spiritual care of older people is one of the ways in which person-centred care can be achieved (Coleman, 2011; Nolan, 2012).

What is spirituality?

Spirituality is a problematic, disputed and evolving concept. There are two extremes to the definition of spirituality; both approaches acknowledge a search for meaning. For some people, divine presence is central; for others, spirituality is a secular concept involving inner life, personal belief and focussing on self. Five ways of thinking about spirituality include:

- Spirituality as part of a religious belief: A particular spirituality is a specific system, or schema of beliefs, virtues, ideals and principles which form a particular way to approach God, and therefore, all life in general (Franciscan spirituality).

- Spirituality as a secular concept: Spiritualties are those ideas, practices and commitments that nurture, sustain and shape the fabric of human lives, whether as individuals or communities (King, 2011: p21).

- Spirituality as a metaphor for absence: Spirituality in all of its diverse forms and meanings names particular inadequacies that have been perceived or sensed within health care and it is these inadequacies that people wish to resist. By raising the importance of meaning, purpose, hope, love, God or relatedness issues that often come to prominence during the experience of being ill, the language of spirituality points towards the gap between experience and current practices and becomes a point of resistance and protest against the absence of some kinds of care (Swinton and Pattison, 2010: p232).

- Spirituality as a search for meaning with or without God: Spirituality recognises the human need for ultimate meaning in life, whether this is fulfilled through a relationship with God or some sense of another, or whether some other sense of meaning becomes the guiding force within the individual's life. Human spirituality can also involve relationships with other people.

- 'Spirituality encompasses wide ranging attitudes and practices which focus on the search for meaning in human lives, particularly in terms of relationships, values and the arts. It is concerned with quality of life, especially in areas that have not been closed off by technology and science. Spirituality may, or may not, be open to ideas of transcendence and to the possibility of the divine' (Ferguson, 2011: xxix)

- The contemporary use of the word 'spirituality': Spirituality refers to the deepest values and meanings by which people seek to live... it implies some kind of vision of the human spirit and of what will assist it to achieve full potential (Sheldrake, 2007: p2).

Spirituality as separate from religion

Paley (2006) notes that it is only recently that spirituality has become separated from religion. He suggests that the growing interest in spirituality amongst nurses is part of the professionalisation of nursing and a 'claim to jurisdiction over a newly invented sphere of work' (p175) that can be seen as part of nursing practice. Nolan (2011), writing as a nurse and healthcare chaplain, has pointed out that there is at the same time a decline in religion and an increase in interest in spirituality. Taylor (2007) offers a detailed account of the rise of the secular age and its implications for society. He traces the change from 'a society in which it was virtually impossible not to believe in God, to one in which faith, even for the staunchest believer, is one human possibility among others' (p3). Heelas and Woodhead (2005) noted the 'massive subjective turn of modern culture' (p2). The turn is away from the focus on life lived as one of God's creatures to life lived subjectively. Based on these accounts, Nolan (2011) suggests that spirituality has become uncoupled from religion.

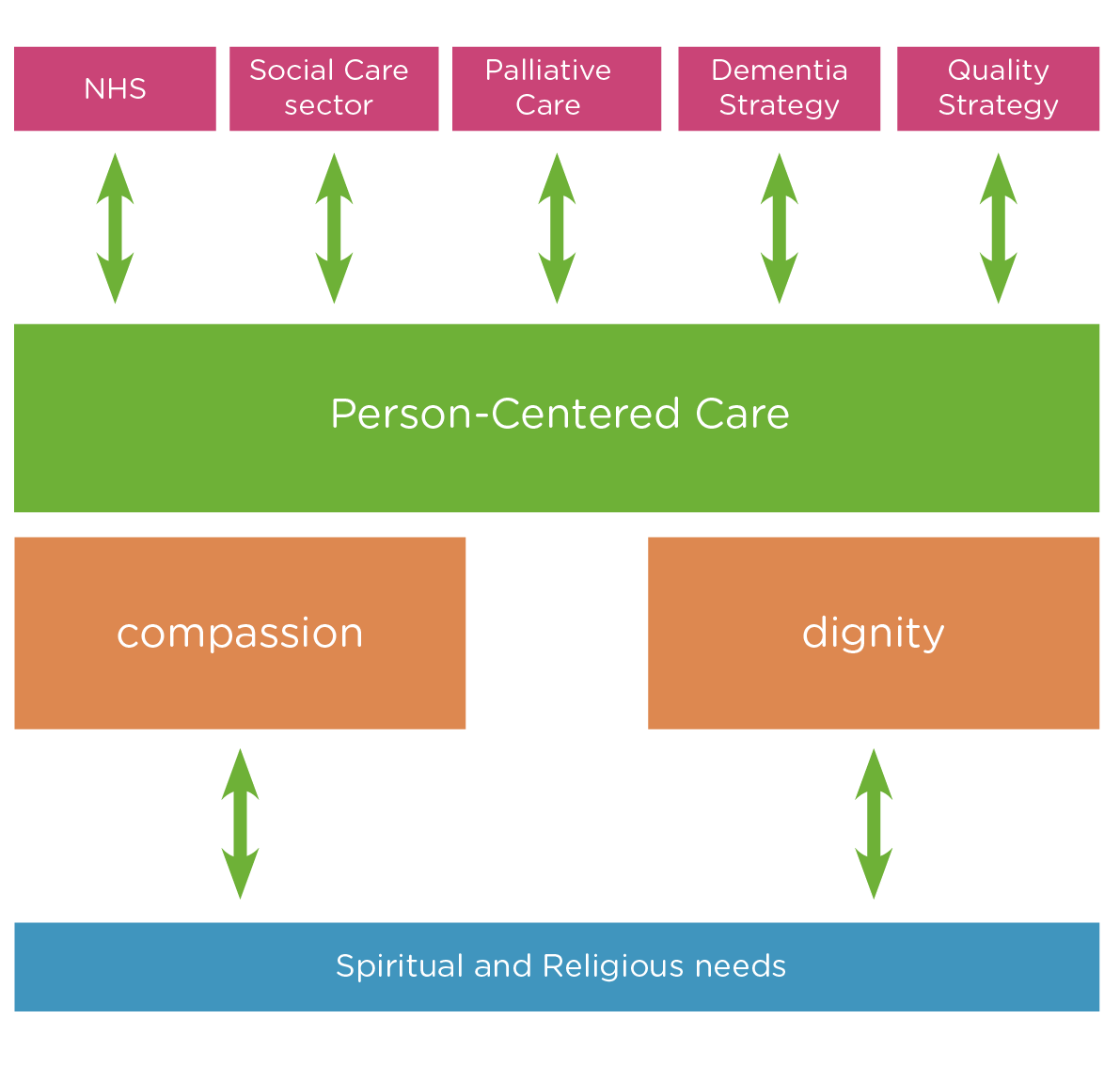

Spiritual care in health and social care policy

There are a variety of health and social care policy drivers for incorporating spiritual care into practice.

1. NHS

Spiritual care is usually given in one-to-one relationship, is completely person centred and makes no assumptions about personal conviction or life orientation.

Religious care is given in the context of shared religious beliefs, values, liturgies and lifestyle of a faith community.

Spiritual care is not necessarily religious. Religious care should always be spiritual. Spiritual care might be said to be the umbrella term of which religious care is a part. It is the intention of religious care to meet spiritual need. (Spiritual Care Matters, 2009)

2. Care sector

'You do not have to alter your values and beliefs in order to receive a service. The principle of valuing diversity means that you are accepted and valued for who you are. The legislation which outlaws discrimination has influenced all the care standards, and the standards in this section make it clear that you can continue to live your life in keeping with your own social, cultural or religious beliefs or faith when you are in the care home.' (Care Inspectorate, The National Care Standards 2007: Standard 12)

3. Palliative care

Meeting the end of life care needs of residents which 'should take into consideration their cultural, spiritual and religious needs and other life circumstances'. (Scottish Government, Living and Dying Well, 2008: Action 15)

4. Dementia care

'Non-discrimination and equality, including rights to be free from discrimination-based age, disability, gender, race, sexual orientation, religious beliefs, social or other status.'

The strategy has a strong focus on 'person-centred care' which incorporates the spiritual element which has been the focus of statements from the World Health Organisation. (Scottish Government, Scotland's National Dementia Strategy, 2010b)

5. World Health Organisation

'Health professions have largely followed a medical model which seeks to treat patients by focussing on medicines and surgery and gives less importance to beliefs and to faith. This reductionist or mechanistic view of patients as being only a material body is no longer satisfactory. Patients and physicians have begun to realise the value of elements such as faith, hope and compassion in the healing process. The value of such 'spiritual elements in health and quality of life has led to research in this field in an attempt to move towards a more holistic view of health that includes a non-material dimension, emphasising the seamless connections between mind and body'.

(WHO, Consultation on Spirituality, Religion and Personal Beliefs, 1998)

The links between person-centred care, dignity and spiritual care

Person-centred care is currently the preferred method of providing care 'that is responsive to individual personal preferences, needs and values and assuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions' (NHS Scotland, 2010: p22). Alongside this strategy is the concept of dignity, developed as a response to poor care (for instance see A Dignified Revolution (ADR)). The Codes of Practice for Social Services Workers identify the importance of respect, trust and upholding confidence (Scottish Social Services Council, 2009). The idea of dignity therapy for older and dying patients developed by Chochinov and colleagues (2005) and Hall and colleagues (2009) is linked to spiritual care. These different discourses point towards the same theme, that the inner person and their values should be the starting point for caring practice.

The theoretical basis for research on spirituality and ageing

Research into ageing and spirituality is based on assumptions of ageing as a journey, as a search for meaning, balance, integration and reconciliation (Mowat, 2004). There are a number of key theorists who have influenced those looking for a theory of ageing and spirituality. These theorists do not directly associate the search for meaning with spirituality; their work has been used by others to build a foundation for particular understandings of spirituality.

- Victor Frankl (1984) posits man's search for meaning as a dominant conscious and unconscious driver. His incarceration in Auschwitz concentration camp during the second world war offered him the opportunity to develop his theories as part of his own survival strategy. His very powerful ideas of the capacity of man to be stripped of all the 'trappings' of life and to still find ultimate meaning underpins much of the work subsequently produced on ageing and spirituality (Kimble, 2000; Mackinlay, 2001).

- Erik and Joan Erikson (1997) theorised stages of life. In each stage, the individual tries to achieve balance between two 'states' with associated virtues. In the later part of life, the balance to be struck is between integration and despair, and the virtue attached to this is wisdom (Capps, 2008). The idea of journey and progression is built into this theory.

- Carl Jung (1960) was particularly interested in the second half of life and the importance of life review to find meaning. He wrote:

one cannot live the afternoon of life according to the program of life's morning: for what was great in the morning will be of little importance in the evening, and what in the morning was true will at evening have become a lie

(Jung, 1970, p399). - Antonovsky (1987) was interested in what psychological processes allow people to maintain themselves in a state of good health. His work on a sense of coherence develops a model and an empirically validated questionnaire which provides clinicians with a tool by which to assess a sense of coherence. A strong sense of internal coherence helps support good health. The work on spirituality and ageing is multidisciplinary, offering fact-based opinion, empirically based research, theory building and philosophical insights.

The research about spirituality, health and ageing

Empirical research into spirituality, health and ageing is dominated by discussions about measurement and method associated with the complications over definition. The early work comes from the United States. There is a much stronger connection in the US between spirituality and religion and so the research tends to focus on the effect of religious practice and belief on health. Observable religious practice is obviously easier to research than 'spirituality'.

Vandeecreek (1995) has gathered key quantitative studies that relate to the work of the health care chaplain as professional spiritual care giver. This specifically excluded qualitative and theory building work. Byrd (1988) conducted a randomised controlled trial investigating the power of intercessory prayer to patients admitted to the Coronary Care Unit in a US hospital. Three hundred and ninety three patients were randomised to an intercessory prayer group or to a control group. While in hospital, the experimental group were prayed for by a group of Christians specifically designated for the task. The control patients (those not prayed for specifically) required ventilation assistance, antibiotics and diuretics more frequently than patients in the prayer group. The conclusion was that prayer has a beneficial affect on patients admitted to a CCU. However, Benson et al (2006) found that prayer does not work in a medical context and further indicates that it can be harmful for some patients.

Distillation of research evidence from over 1,200 empirical studies and 400 reviews by Koenig and colleagues (1994; 2001) has shown an association between faith and religious practice and health benefits, including protection from illness, coping with illness and faster recovery. Koenig (1994) identified 14 spiritual needs of older people based on prior research both at a theoretical and empirical level. Koenig here is specifically talking about religion and the various practices that emerge from participation in religion. He has done no work on the more generic understandings of spirituality that are highlighted earlier. This distinction is important as the word 'spirituality' is multi-vocal and is required to be used with clarity and caution if an argument is to be made for its use. However, this list below does provide a starting point as many of the concepts are understandable in a non-religious context.

- Need for support in dealing with loss

- Need to transcend circumstances

- Need to be forgiven and to forgive

- Need to find meaning, purpose and hope

- Need to love and serve others

- Need for unconditional love

- Need to feel that God is on their side

- Need to be thankful

- Need to prepare for death and dying

- Need for continuity

- Need for validation and support of religious behaviours

- Need to engage in religious behaviours

- Need for personal dignity and sense of worthiness

- Need to express anger and doubt

The practice of spiritual care for older people

The practice of spiritual care with older people is less contentious than the definitions of spirituality. There is a growing shared understanding that 'meaning making' and 'life review' are important spiritual processes which can manifest themselves in a variety of ways. Some of the activities to support spiritual care are explored below.

1. Spiritual reminiscence

Talking about previous religious and spiritual events gives both carers and older people a chance to review spiritual needs and develop new friendships with, and knowledge of, each other. Mackinlay and Trevitt (2010) allocated 113 people with dementia to groups for periods between six weeks and six months. Qualitative and quantitative data was collected which showed that life story work with an emphasis on spirituality helped develop stronger relationships between staff and residents and allowed for discussions about meaning to take place.

2. Spiritual history

Spiritual history taking involves asking about the importance of faith and beliefs to the person. Pulchalski's (2006) model was developed for physicians in the USA. It focuses on asking about faith, the importance of faith to the patient, the community of the patient and the action, if any, that the patient would like regarding their faith in their current context. Pulchalski (2006) found that this trigger discussion can be referred to later as the patient becomes less well and signposts future caring practice. Atchley (2009:160) offers a spirituality inventory.

3. Life review / life story

Birren and Schroots (2006) researched the value of life review and set up the Guided Autobiographical Group (GAB). His findings showed that GAB provided increased sense of personal power and importance and enhanced adaptive capacities, drawing on forgotten or dormant skills. This allowed people to face end of life matters with confidence.

The TSAO foundation for successful ageing in Singapore suggested that there are three stages to GAB:

- A general group discussion around a specific theme to trigger the process of self awareness and life review

- Small group work that discusses a specific theme at a deeper level

- Individual work, either in writing or by audio recording on a specific theme

4. Music / song

The positive effects of music and singing on wellbeing are noted in Lipe's (2002) review. Robertson-Gillam (2008) carried out a pilot study to test the potential for choir work to reduce depression and increase quality of life in people with dementia, and to look at the extent to which it met their spiritual needs. Twenty nine participants were assigned to one of three groups: choir, reminiscence and control. Results indicated increased levels of motivation and engagement. Learning the lyrics evoked long-term memory with religious and spiritual meanings for choir members. Both the choir and the reminiscence group showed improved levels of purpose and wellbeing using the Spirituality Index of Wellbeing (Daaleman and Frey, 2004).

5. Worship / prayer / ritual

Providing continuity for older people in terms of their familiar rituals and routines sustains memory and wellbeing. Atchley's (2009) longitudinal study of 1300 people over 20 years from 1975 showed that continuity of activities occurred most commonly for reading, being with friends, being with family, attending church and gardening. Goldsmith (2004) identifies the importance of continuity of worship and using familiar signs and symbols as part of that, as well as the capacity to create forms of worship that tap into spiritual memory.

6. Presence / being there

The reflective self as a presence for others helps the spiritual journeys of others. Kelly (2012) discusses the use of the person themself as the resource by which spiritual care can be delivered. This follows on from Speck's (1988) work which shows that the calm and unpressured presence of the chaplain can provide support in times of difficulty and when in search for meaning.

7. Listening

Careful listening is a spiritual practice. Recent research into community chaplaincy listening (Mowat et al, 2012) shows that in intentionally listening to another, the gift of time and attention is offered, as well as support for the spiritual work of hope, meaning and purpose.

Conclusion

The ageing population requires person-centred care and developmental support in order to maximise its chances of ageing well. Spirituality, although a contested concept, is evolving and developing and can be defined as a search for meaning with or without religious adherence. Person-centred care involves spiritual care - the time, attention and listening to support individuals to find meaning and purpose in their lives. It has been established that there are a range of activities and practices which can support these dimensions of spiritual care.

References

- Antonovsky A (1987) Unraveling the mystery of health: how people manage stress and stay well, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

- Atchley R (2009) Spirituality and ageing, Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press

- Benson H, Dusek J, Sherwood J et al (2006) Study of the therapeutic effects of intercessory prayer (STEP) in cardiac bypass patients: A multicenter randomized trial of uncertainty and certainty of receiving intercessory prayer, American Heart Journal, 151, 934-42

- Birren J and Schroots J (2006) Autobiographical memory and the narrative self over the life span, in J Birren and K Schaie (eds) Handbook of the psychology of aging, San Diego: Academic Press

- Byrd R (1988) Positive therapeutic effects of intercessory prayer in a coronary care unit population, Southern Medical Journal, 81, 826-829

- Capps D (2008) The decades of life: a guide to human development, London: Westminster John Knox Press

- Chochinov H, Hack T and Hassard T et al (2005) Dignity therapy: A novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life, Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23, 5520-5

- Coleman P G (2011) Belief and Ageing: spiritual pathways in later life, Bristol: Policy Press

- Daaleman T and Frey B (2004) The spirituality Index of Well Being: A new instrument for health related quality of life research, Annals of Family Medicine, 2, 5

- Erikson E and Erikson J (1997) The life cycle completed: extended version, New York: Norton and Co

- Ferguson R (2011) George Mackay Brown: the wound and the gift, Edinburgh: St Andrew Press

- Frankl V (1984) Man's search for meaning, New York: Washington Square Press

- Goldsmith M (2004) A strange land: People with dementia in the local church, Southwell: 4M Publications

- Hall S, Longhurst S and Higginson I (2009) Living and dying with dignity: A qualitative study of the views of older people in nursing homes, Age and Ageing, 38, 411-416

- Heelas P and Woodhead L (2005) The spiritual revolution: why religion is giving way to spirituality, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

- Jung C G (1970) Collected works (Volume 8), New Jersey: Princeton University Press

- Kelly E (2012) Personhood and presence: self as a resource for spiritual and pastoral care, London: T and T Clark International

- Kimble M (2000) Victor Frankl's contribution to spirituality and ageing, New York: Haworth Press

- King U (2011) Can spirituality transform our world, The Journal for the Study of Spirituality, 1, 17-34

- Koenig H (1994) Ageing and God: spiritual pathways to mental health in midlife and later years, New York: The Haworth Pastoral Press

- Koenig H, McCullough M and Larson D (2001) Handbook of religion and health, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Lipe A (2002) Beyond therapy: music, spirituality, and health in human experience - a review of the literature, Journal of Music Therapy, 39, 209-240

- Mackinlay E (2001) The spiritual dimension of ageing, London: Jessica Kingsley Publications

- Mackinlay E and Trevitt C (2010) Living in aged care: Using spiritual reminiscence to enhance meaning in life for those with dementia, International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 19, 394-401

- Mowat H (2004) Successful ageing and the spiritual journey, in A Jewell (ed) Ageing spirituality and wellbeing, London: Jessica Kingsley

- Mowat H (2008) The potential for efficacy of healthcare chaplaincy and spiritual care provision in the NHS (UK). Report available from NHS Education Scotland, Health care chaplaincy department

- Mowat H (2011) Voicing the spiritual: Working with people with dementia, in A Jewell (ed) Spirituality and personhood in dementia, London: Jessica Kingsley Publications

- Mowat H, Bunniss S and Kelly E (2012) Community chaplaincy listening: Working with general practitioners to support patient wellbeing, Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 15 (1), 21-26

- NHS Education for Scotland (2011) Bridging the gap: A health inequalities learning resource

- NHS Scotland (2010) The Healthcare Quality Strategy for NHS Scotland, Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- Nolan S (2011) Psychospiritual care: New content for old concepts - towards a new paradigm for non religious spiritual care, Journal for the Study of Spirituality, 1 (1), 50-64

- Nolan S (2012) Spiritual care at the end of life: the chaplain as "hopeful" presence, London: Jessica Kingsley

- Paley J (2006) Spirituality and secularisation: Nursing and the sociology of religion, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17, 175-186

- Pulchalski C (2006) A time for listening and caring: spirituality and the care of the chronically ill and dying, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Robertson-Gillam K (2008) Hearing the voice of the elderly: The potential for choir work to reduce depression and meet spiritual needs, in E Mackinlay (ed) Ageing, Disability and Spirituality: addressing the challenge of disability in later life, London: Jessica Kingsley

- Scottish Government (2010a) Demographic Change in Scotland, Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- Scottish Government (2010b) Scotland's national dementia strategy, Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- Scottish Social Services Council (2009) Codes of practice for social service workers and employers, Dundee: Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC)

- Sheldrake P (2007) A brief history of spirituality, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

- Speck P (1988) Being there, London: SCM Press

- Spiritual Care Matters (2009) An introductory resource for all NHS Scotland staff

- Swinton J and Pattison S (2010) Moving beyond clarity: Towards a thin, vague and useful understanding of spirituality in nursing care, Nursing Philosophy, 11, 226-237

- Taylor C (2007) A secular age, London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Thane P (ed) (2005) The long history of old age, London: Thames and Hudson

- Vandecreek L (ed) (1995) Research in pastoral care and counseling: readings in research, Journal of Pastoral Care Publications

- World Health Organisation (1998) Quality of life report: Social change and mental health cluster - consultation on spirituality, religion and personal beliefs

Acknowledgements

This Insight was written by Harriet Mowat and Maureen O'Neill (Faith in Older People) and has been reviewed by Elizabeth MacKinlay (Charles Sturt University), Neil Macleod (SSSC), John Swinton (University of Aberdeen) and Gordon Watt (Scottish Government). Iriss is very grateful to them for their input.