This Insight is based on the key findings of a review conducted for ADSW (Petch, 2011), which considered the evidence base for health and social care integration. Written by Alison Petch (Iriss)

Key points

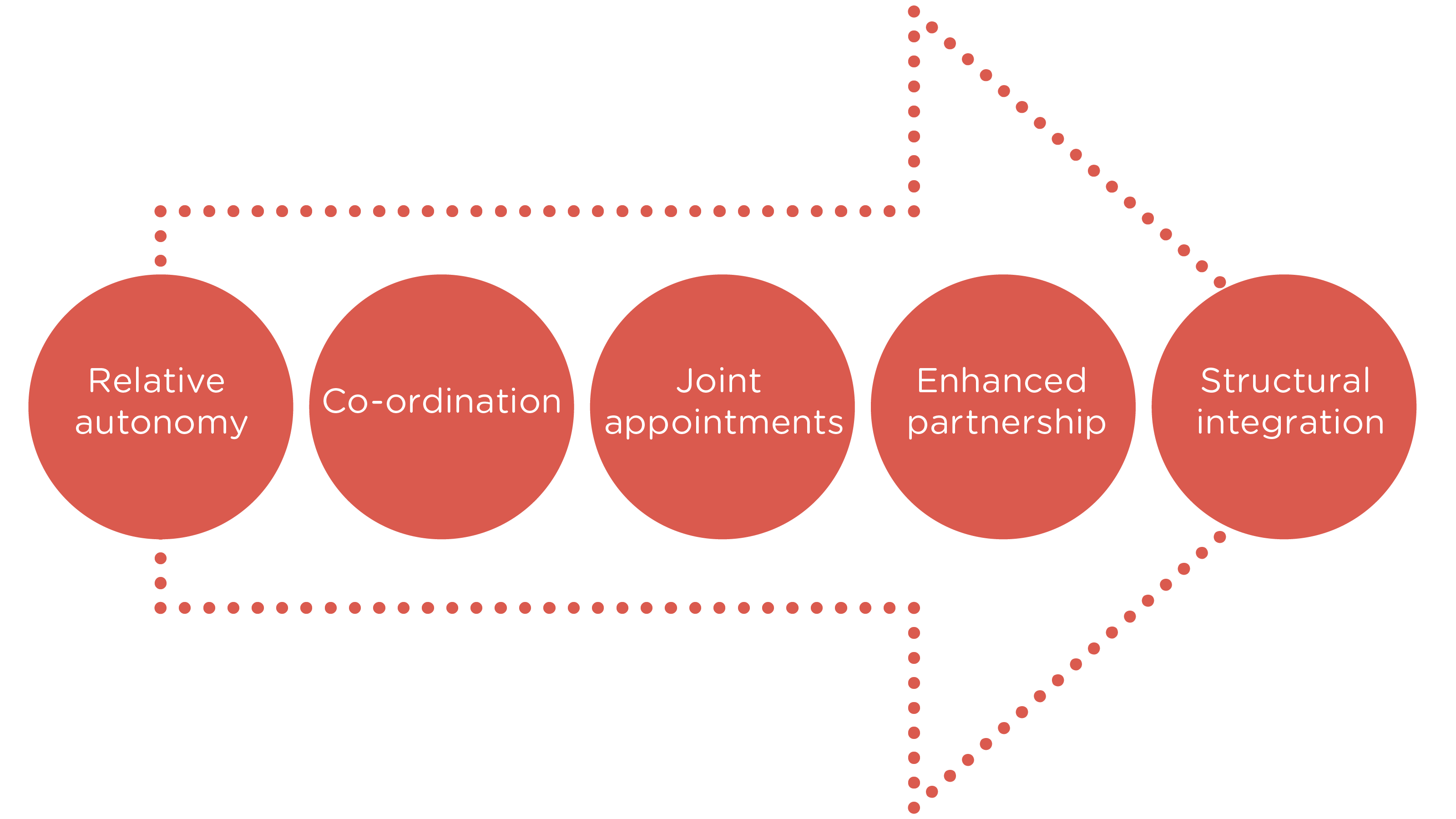

- Any discussion of integration requires careful definition to ensure common understanding. A helpful characterisation is of a continuum extending from relative autonomy to structural integration.

- Three levels of integration can also be identified: macro (strategic); meso (service level); and micro (individual user).

- Much of the evaluation of partnership working has focused on the process, rather than on whether it has an impact on individual outcomes. More recent evidence, particularly from a number of international projects, is promising.

- There is as yet no robust evidence for positive financial benefits from integration.

- Structural integration fails to deliver the aspirations set for it.

- The examples of 'early adopters' cited from England embrace a diversity of approaches.

- The appropriate focus is on the dimensions that contribute to effective delivery across health and social care at the local level. These include culture, leadership, and a focus on outcomes for individuals.

Introduction

This Insight is based on the key findings of a review conducted for ADSW (Petch, 2011), which considered the evidence base for health and social care integration. Following discussion on the importance of clear definitions, the main conclusions from this review are highlighted. The experiences of early adopters of different forms of health and social care integration are discussed. A further Insight will address the evidence relating to the most effective ways of achieving integrated team working.

Defining partnership working and integration

It is essential in any discussion of health and social care integration that people define what they are talking about. Otherwise there is a real danger that people are either referring to a similar arrangement using different terms or using the same term to refer to different configurations. This confusion has been widely acknowledged: a 'slippery concept'; 'methodological anarchy and definitional chaos'; and a 'terminological quagmire'.

From the range of attempts to define a continuum across this field, two can be selected as particularly useful. Edwards (2010) addresses the different degrees of collaboration across organisational boundaries:

- Autonomy is when agencies act without reference to each other, although their actions may affect one another.

- Co-operation is when parties show a willingness to work together with an emphasis on communication.

- Co-ordination is when considerable effort is put into harmonising the activities of agencies so that duplication is minimised. This is often characterised by the activity of a third party to coordinate and the existence of agreed protocols.

- Integration is when the boundaries begin to dissolve and new work units emerge.

A second analysis, presented diagrammatically below, was developed for a survey conducted by the NHS Confederation and the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS) in England in 2010 (NHS Confederation 2010).

The characteristics for each of these categories were:

- Relative autonomy: the local authority and NHS meet statutory requirements for formal partnership working, but most co-ordination is largely informal

- Co-ordination: there is a reasonable level of formal commitment to joint working, with co-ordination around some areas of strategy and/or commissioning, depending on circumstances

- Joint appointments: health and the local authority have some key joint appointments and the teams collaborate but are not integrated/combined

- Enhanced partnership: a system-wide commitment, shared vision and integration across most strategic and commissioning functions, senior and middle-tier joint appointments, formal high-level backing, but separate entities remain

- Structural integration: health and local authority care services have formed a single integrated legal entity (a care trust in England) or a combined service (joint PCT and social care department in England).

This survey also asked respondents to identify the factors that they considered had helped or hindered integrated working locally. The findings are important. The top five factors enhancing integrated working were all local and within the control of the partnership organisations:

- Friendly relationships

- Leadership

- Commitment from the top

- Joint strategy

- Joint vision

Conversely, all those seen to hinder integrated working were external, the majority nationally determined: performance regimes; financial pressures; organisational complexity; changing leadership; and financial complexity.

It is also important to distinguish integrated organisations from integrated care. In a review of integrated care for older people, Reed et al (2005:2) offer a useful typology. They identify integration:

- Between service sectors (ie health and social care)

- Between professions (ie nurses, social workers, doctors, physiotherapists)

- Between settings (ie institutions and community, primary and secondary care)

- Between organisation types (statutory, private and voluntary)

- Between types of care (ie acute and long-term care)

...and suggest a distinction between macro strategies (taking place at the societal level), mezzo strategies (at a service system level), and micro strategies (occurring at an individual service user level).

A similar three-fold distinction is also drawn by Curry and Ham (2010) in their discussion of clinical and service integration. They review examples of integration at three levels. At the macro level, providers, either together or with commissioners, seek to deliver integrated care to the populations they serve. At the meso level, providers seek to deliver integrated care for a particular care group or population with the same disease or conditions. Finally, at the micro level, the focus is on the delivery of integrated care for individual service users and their carers.

It is important to note that much of the discussion of integration from a health perspective refers to integration within health rather than between health and social care (for example managed clinical networks, virtual wards). A useful distinction which informs such debate is between vertical and horizontal integration. Horizontal integration refers to services or organisations coming together to deliver care and support at the same level (eg mergers of acute hospitals, formation of care trusts); vertical integration occurs when services (again single or multi-agency) come together to deliver care and support at different levels (eg secondary and tertiary care).

The evidence base for partnership and integrated working

Although clarity of definition is an essential prerequisite, the critical consideration must be the impact of different forms of partnership working - what difference, if any, does working in partnership make (Hudson and Hardy, 2002; Glendinning, 2002; Glendinning et al, 2005). An early systematic review of the factors promoting and obstacles hindering joint working by Cameron et al (2000) concluded that there was a 'dearth of research evidence to support the notion that joint working between health and social care services is effective' (p23). However, El Ansari et al (2001) have highlighted the complexities of establishing the evidence base for partnership working: micro versus macro scale; short term versus long term; the challenge of capturing an evolving process; the uncertainties of attribution in the complex mix of factors that contributes to partnership working.

A key distinction was crystallised by Dowling et al (2004) who highlighted that much of the research had focused on the process of partnership working - how individuals and partners worked together, the extent of common agreement as to purpose, levels of trust and reciprocity. Few had considered partnership working from the perspective of whether it made a difference to those on the receiving end, on the outcomes of partnership working for individuals. This is a critical distinction and must be central to any discussion of the effectiveness of partnership working.

Early studies did not provide the definitive evidence that might be expected. A number of international studies, however, have had somewhat more promising results, leading to a (modest) number of projects which are often cited (Ham et al, 2008; Glasby and Dickinson, 2009; Curry and Ham, 2010). In North America these include the OnLok demonstration project which became PACE in the USA; the Quebec-based SIPA; and the Canadian PRISMA. High profile programmes in Europe include CARMEN; PROCARE and the Vittorio Veneto and Rovereto projects in Italy. Evaluations of the OnLok, Vittorio Veneto and Rovereto initiatives all suggested that integrated working reduced the cumulative number of days older people stayed in institutional care. Common features of these projects are case management, geriatric assessment and a multi-disciplinary team; a single entry-point; and financial levers. The challenge, however, is to translate these features from the demonstration project to the mainstream.

The somewhat contradictory nature of the research messages on individual outcomes has led in recent years to arguments for a more nuanced approach. The focus it is suggested should be on 'what sort of partnerships can produce what kinds of outcomes for which groups of people who use services, when and how' (Dickinson, 2006).

The financial evidence

Any discussion of partnership working, whether focusing on outcomes or more broadly, needs to acknowledge the centrality of the financial context. In the context of the development of the Integrated Resource Framework, Weatherly et al (2010) were commissioned by Scottish Government to conduct a rapid review on the evidence on financial integration across health and social care. The authors concluded that there was 'tentative evidence that financial integration can be beneficial. However, robust evidence for improved health outcomes or cost savings is lacking' (p3). In particular, 'there is no robust evidence on whether improved outcomes can be achieved in the longer term' (p31). Moreover, 'the cost of integration can be substantial and costs may increase in the short term' (p31).

The review identified two factors that it considered critical for any success in this area. Firstly, there needs to be a clear, joined-up vision. Different perspectives need to be acknowledged if any partnership is to flourish. Secondly, a one-size-fits-all approach should be avoided: 'the type and degree of integration should reflect programme goals and local circumstances' (p30).

The limits of structural change

The evidence base in some of the areas discussed above is tentative. It is more definitive, however, in respect of major structural change failing to deliver. This is demonstrated by Northern Ireland, 'one of the most structurally integrated and comprehensive models of health and personal social services in Europe' (Heenan and Birrell, 2006:48). Heenan and Birrell (2009) suggest that despite a number of achievements, there have been a number of significant limitations. Importantly, a hegemony of health appears to persist, with health continuing to dominate the agenda. Social care values and priorities appear to be subsumed by a dominant health system. Likewise, the resource focus is on the acute sector, with evidence of funding being diverted to this agenda with its higher public and media profile. The new structures are large bodies with their membership dominated by health. A second concern is the priority attached to health agendas and targets, for example the focus on the prevention and control of hospital infection. A further concern is the limited focus of the integrated approach, with an apparent reluctance to innovate. There is little evidence, for example, of progressive development of direct payments and individual budgets, of personalisation, and of children's services. Finally, integration has not realised its full potential. There has been little interest in strategic review and little attention paid to the potential opportunities offered by an integrated structure. The experience of Northern Ireland highlights the critical importance of a 'culture of integration':

This culture must permeate all levels of service planning and provision in order to provide an integrated mindset. What was apparent form this study was that the integrated structure itself had not automatically led to integrated practices... Integration was not really about structures or patterns of working; it was fundamentally a way of thinking. It required a shared vision and a mutual willingness to change and compromise.

(Heenan and Birrell, 2006:63)

Field and Peck (2003) have made an interesting contribution to the debate on health and social care structures through their analysis of mergers and acquisitions in the private sector. They suggest that these do not paint an optimistic picture. Mergers are potentially very disruptive to managers, staff and people who use services and can give a false impression of change. They can stall positive service development and productivity for at least eighteen months and typically do not save money.

Early Adopters

There are a number of examples of 'early adopters' of various forms of integrated working in England which are often highlighted (Ham and Oldham, 2009). It is important to recognise that these examples embrace a diversity of approaches.

Torbay

The experience of Torbay illustrates both the significance of local history and context and the lengthy development time. Initial discussions on increased collaboration in the wake of poorly performing social services led to a number of joint appointments and to piloting of an integrated, co-located team of community health and social care staff, centred on three local GP practices. A locality general manager (from social services) and subsequently a merged post of PCT chief executive and director of social services was created, and the decision made to become a Care Trust. Key to this period of change was a focus throughout on the 'getting it right for Mrs Smith', a persona for an 80-year-old user of a fragmented range of services. Discussions with staff explored the challenges for Mrs Smith in navigating the local health and social care system, including multiple assessments, lack of shared information and the complexity of the system.

Knowsley

The Knowsley Health and Wellbeing Partnership has adopted a different approach, established through the s31 flexibilities of the 1999 Health Act and working through a joint post of PCT Chief Executive and Council Executive Director and through a jointly chaired Partnership Board. The vision behind partnership working in Knowsley is of 'working together for a better, healthier life for everyone in Knowsley', with the initiative more recently extended to embrace leisure and cultural services. The most significant feature of the Knowsley model is that through local leadership and long-term commitment it has achieved service integration without structural integration.

North East Lincolnshire

As in Torbay, the story in North East Lincolnshire is of an evolving response over a number of years in an area characterised by poor local authority leadership. In 2007, the North East Lincolnshire Care Trust Plus was established. Responsibility for adult social care commissioning and provision was transferred from the local authority to the PCT; responsibility for public health was transferred to the local authority. Four localities provide the basis for commissioning, each around 40,000 in population.

Somerset

The detailed evaluation of the Somerset Partnerships Health and Social Care NHS Trust, established in 1999 as the first integrated provider for mental health, highlights the key role of culture (Peck et al, 2001). Fundamental was the 'culture' to be adopted by the partnership - whether it should be a new and different culture or an enhancement of the cultures already in place in the merging bodies.

Is the desired result one entirely new culture, albeit comprised of elements taken from all the current professional cultures - the melting pot approach to culture? Or is the desired result the enhancement of the current professional cultures by the addition of mutual understanding and respect - the orange juice with added vitamin 'c' approach to culture (p325).

Sedgefield

The final example is at a more local level: the integration of social workers, district nurses and housing officers on a locality basis in Sedgefield, County Durham, establishing five co-located front-line teams to serve the area. Resources were pooled, the joint operational teams were under single management, and a local partnership board was created to oversee the arrangements. Evaluation provided evidence to support the integrative nature of a focus on the whole person, nurtured by the mutual understanding emerging from the co-location. This, Hudson (2006) argues, can generate the 'holy grail of integration: acceptance of collective responsibility for a problem, as opposed to the pursuit of narrow professional concerns' (p16). The critical factor in the Sedgefield experience is the focus on the development of effective teams rather than on structure.

Conclusion

There is clear evidence that structural integration does not deliver effective service improvement. The emphasis should be on service integration rather than on organisational integration. Moreover the focus should be on the specific aspects of individual partnerships which deliver particular outcomes for identified groups. There are a number of key dimensions which contribute at the local level to effective service delivery across health and social care. These include the importance of culture; the role of leadership; the place of local history and context; time; policy coherence; the need to start with a focus on those who access support; a clear vision; and the role of integrated teams.

The journey towards integration needs to start from a focus on service users and from different agencies agreeing a shared vision for the future, rather than from structures and organisational solutions.

(Ham, 2009:9)

Acknowledgements

This insight has been reviewed by Karl Stern (Perth and Kinross Council). We are very grateful to Karl for his input.

References

- Cameron A, Lart R, Harrison L, Macdonald G and Smith R (2000) Factors promoting and obstacles hindering joint working: a systematic review, Bristol: Policy Press

- Curry N and Ham C (2010) Clinical and service integration: the route to improved outcomes, London: King's Fund

- Dickinson H (2006) The evaluation of health and social care partnerships: An analysis of approaches and synthesis for the future, Health and Social Care in the Community, 14, 375-383

- Dowling B, Powell M and Glendinning C (2004) Conceptualising successful partnerships, Health and Social Care in the Community, 12, 309-317

- Edwards A (2010) Working across the health and social care boundary, in J Glasby and H Dickinson (eds) International perspectives on health and social care, Oxford: Wiley Blackwell

- El Ansari W, Phillips C and Hammick M (2001) Collaboration and partnerships: Developing the evidence base, Health and Social Care in the Community, 9, 215-227

- Field J and Peck E (2003) Mergers and acquisitions in the private sector: What are the lessons for health and social services? Social Policy and Administration, 37, 742-755

- Glasby J and Dickinson H (eds) (2009) International perspectives on health and social care, Oxford: Wiley Blackwell

- Glendinning C (2002) Partnerships between health and social services: Developing a framework for evaluation, Policy and Politics, 30, 115-127

- Glendinning C, Dowling B and Powell M (2005) Partnerships between health and social care under 'New Labour': Smoke without fire? A review of policy and evidence, Evidence and Policy, 1, 365-381

- Ham C (2009) Only connect: Policy options for integrating health and social care, London: The Nuffield Trust

- Ham C, Glasby J, Parker H and Smith J (2008) Altogether now? Policy options for integrating care, University of Birmingham: Health Services Management Centre

- Ham C and Oldham J (2009) Integrating health and social care in England: Lessons from early adopters and implications for policy, Journal of Integrated Care, 17, 6, 3-9

- Heenan D and Birrell D (2006) The integration of health and social care - the lessons from Northern Ireland, Social Policy and Administration, 40, 47-66

- Heenan D and Birrell D (2009) Organisational integration in health and social care: Some reflections on the Northern Ireland experience, Journal of Integrated Care, 17, 5, 3-12

- Hudson B (2006) Integrated team working: you can get it if you really want it - Part I, Journal of Integrated Care, 14 (1), 13-21

- Hudson B and Hardy B (2002) What is a 'successful' partnership and how can it be measured?, in C Glendinning, M Powell and K Rummery (eds) Partnerships, New Labour and the `Governance of Welfare, Bristol: Policy Press

- Peck E, Towell D and Gulliver P (2001) The meaning of 'culture' in health and social care: A case study of the combined trust in Somerset, Journal of Interprofessional Care, 15, 319-327

- Petch A (2011) An evidence base for the delivery of adult services, Edinburgh: Association of Directors of Social Work

- Reed J, Cook G, Childs S and McCormack B (2005) A literature review to explore integrated care for older people, International Journal of Integrated Care, 5, www.ijic.org

- Weatherly H, Mason A, Goddard M and Wright K (2010) Financial integration across health and social care: evidence review, Edinburgh: Scottish Government Social Research