Key points

- Supervision is an essential component of practice in social work and social care, not just for frontline staff, but at all levels in an organisation

- Effective supervision provides a safe space for workers to reflect on their practice, as well as to develop skills and knowledge

- The delivery of supervision is heavily dependent on the organisational context

- While the evidence base on supervision is limited, the available evidence points to good supervision being associated with job satisfaction, organisational commitment and retention of staff

- The dynamics of supervision can be extremely complex, and delivering effective supervision is a skilled task which requires support and training for supervisors

Introduction

Supervision in social work and social care is a 'key organisational encounter' (Middleman and Rhodes 1980, p52). However, although much has been written about this topic, the evidence base is limited. This review seeks to explore the relevant literature and focus on a number of themes in more detail. It will begin by looking at the key functions of supervision before exploring supervision in two specific contexts: integrated settings and child protection. One model of supervision, the 4 x 4 x 4 model (Wonnacott, 2012) will be explored, because it both promotes reflective supervision and locates it firmly within its organisational context. This review will then turn to two important approaches to supervision: outcomes-focused and reflective supervision. The dynamics of the supervision process will then be explored and effective supervision skills identified. The emphasis in this review is on individual 1-1 supervision, but attention will also be paid to group supervision because of its use in a range of social care settings. Further resources to support supervisors can be found on the SSSC Step into Leadership website.

This Insight was written by Martin Kettle, Glasgow Caledonian University.

What do we mean by supervision?

It is important at the outset to look at the definition of supervision. There are a number of definitions, some of which are lengthy and detailed (see for example, Davys and Beddoe, 2010; Hawkins and Shohet, 2012). Morrison (2006, p32) defines supervision as:

A process by which one worker is given responsibility by the organisation to work with another worker(s) in order to meet certain organisational, professional and personal objectives.

Writing in a social care context, the Care Council for Wales (2012), in a more organisationally focused approach, defines supervision as:

an accountable, two-way process, which supports, motivates and enables the development of good practice for individual social care workers. As a result, this improves the quality of service provided by the organisation. Supervision is a vital part of individual performance management.

This second definition has a much stronger emphasis on the organisational context within which supervision is conducted.

Functions

Whilst there may be broad consensus on what supervision is about, there are differences when it comes to exploration of its key functions. Kadushin (1992) argues that there are three main functions: educational, supportive and administrative. The educational or development function concerns the development of knowledge, skills and, importantly, attitude toward the worker's role. In this function, the goals of supervision are seen to encourage reflection and exploration of the work and to develop new insights, perceptions and ways of working. The supportive function involves supervisors providing support for both the practical and psychological elements of a practitioner's role. Hughes and Pengelly (1997) argue that attending to the emotional response to the work is more important than merely support. In this function, the primary issue can be seen as being the emotional impact of practice and the potential of this to undermine safe practice, as well as the impact on health and wellbeing of the practitioner. Lastly, the administrative or management function concerns the promotion and maintenance of good standards of work and the adherence to organisational policies and those of other key stakeholders, including professional bodies and the Care Inspectorate. This can be viewed as the quality assurance dimension within supervision. Morrison (2006) suggests that supervision has a fourth function of mediation, which involves providing a link between the worker and the broader organisation.

It is recognised that there are tensions between different functions. Peach and Horner (2007) and Beddoe (2010) identify tensions between what they refer to as surveillance on the one hand and support or reflection on the other.This points to the importance of adopting a critical perspective on supervision. In addition, Malahleka (1995) suggests that there is a tension between interface (mediation) and interference (scrutiny).

Context

Supervision is clearly located within its organisational context (Noble and Irwin, 2009). It is contended that supervision takes place at the intersection of four systems: political, service, professional and practice (Baines et al, 2014). The broader political culture within which social work and social care operates has changed considerably in recent years, with a much stronger emphasis on agency accountability (Peach and Horner, 2007). However, it is argued by Jones (2004) that learning is inextricably linked to questions of accountability - 'What is it that practitioners are learning to do, how well are they doing it and to whose benefit?' Further, it is argued that there is an increased emphasis on risk (Beddoe, 2010) and on the organisational aspect of supervision at the expense of attention to practice issues (Hughes and Olney, 2012).

Organisational culture can be a very strong influence on supervision, with Hawkins and Shohet (2012) claiming that the best and worst features of the organisation often accompany participants into supervision. Similarly, Lawlor (2013), in a study of developing a reflective approach to supervision in one agency, stresses the importance of leadership from the very top of the organisation.

The optimum context for effective supervision is within a broader learning and development culture, characterised by the following features:

- Reviews of mistakes and problems provide opportunities for learning, not finding scapegoats

- There is organisational commitment to continuing professional development throughout workers' careers

- Room is found for professional autonomy and discretion, and practice which is not dominated by rule-bound proceduralism

- The emotional impact of the work is recognised with effective processes to mitigate the worst effects

- Individuals and teams make the time to review their effectiveness

(Schon, 1983; Hughes and Pengelly, 1997; Davys and Beddoe, 2010)

Evidence base

There is an apparent paradox in that whilst the importance of supervision has been increasingly recognised in recent years (Hawkins and Shohet, 2012), the evidence base has not reflected this. For example, after reviewing 690 articles about supervision in child welfare, Carpenter and colleagues (2013, p1843) concluded that, 'the evidence base for the effectiveness of supervision in child welfare is surprisingly weak'. They note that there are many models of supervision, but few of them have been subjected to rigorous research. The most obvious gap is in evidence that the implementation of clearly defined models of supervision in an organisation leads to improved outcomes for workers and, in particular, people who access support. As Fleming and Steen (2004) point out, there are a number of causal links and intervening variables that make the task of building an evidence base very challenging.

Taking a broader approach than child welfare, Davys and Beddoe (2010) point out that there remains little agreement as to what constitutes 'good' supervision and that much evaluative research into effectiveness has focused on supervision of students. In particular, the impact of supervision on outcomes for service users and carers has rarely been investigated (Carpenter et al, 2012), although there is some evidence which suggests that supervision may promote empowerment, fewer complaints and more positive feedback (Local Government Association, 2014). Two recent and large-scale studies of the views and experiences of newly qualified social workers in Scotland (Grant et al, 2014) and England (Manthorpe et al, 2015) both paint very mixed pictures of the experience of receiving supervision, with those who do receive regular supervision finding it very helpful in terms of their professional development, and others finding supervision to be infrequent and focused purely on its administrative function.

However, whilst there is limited robust research, what evidence there is points to good supervision being associated with job satisfaction, organisational commitment and retention of staff (SCIE, 2012). There is also an apparent link between employees' perceptions of the support they receive from the organisation and perceptions of their own effectiveness. In short, good supervision does appear to have a positive impact on practice, although more rigorous research is needed. This Insight will now turn to a brief exploration of supervision in two specific, but significant contexts, namely integrated settings and child protection. These areas have been chosen because of the currency of the integration agenda and the volume of literature that relates to child protection. In selecting these areas to highlight in this brief review, it is important to stress that supervision is just as important in other areas of social work and social care practice.

Integration

Evidence on supervision in integrated settings is limited, and of particular importance as integration of health and social care gathers pace in Scotland in particular. One recent exception (SCIE, 2013) explored the delivery of supervision in a range of joint and integrated team settings within adult care in England. Leadership was found to be particularly important in establishing a learning culture as well as supporting innovation. This piece of research explicitly sought to address the perspectives of people who use services on supervision, an aspect that is significantly under-represented in the literature. People who use services were unclear about the purpose of supervision, and concerns were expressed about decisions being made without their input into the process. The lack of research highlights the importance of paying attention to this area as the integration agenda develops.

Child protection

Supervision of child protection work is an area that has come under particular scrutiny. The emotional impact of child protection work is well documented (Harvey and Henderson, 2014). In her review of child protection in England, Munro (2010, 2011) identifies that there can be a high personal cost to being exposed to powerful and often negative emotions involved in this area of work. A lack of effective supervision increases the risk of burnout, which can be defined as emotional exhaustion, cynicism and reduced personal accomplishment.

Evidence from Serious Case Reviews where children have died or been seriously harmed at the hands of parents or carers (Brandon et al, 2008; Vincent and Petch, 2012) indicates that inadequate supervision, or supervision that is overly focused on administrative aspects, risks losing the focus on the child, with the potential for fatal consequences. This theme is explored by Laming (2009, p32) who identified a concern that, 'the tradition of deliberate, reflective social work practice is being put in danger because of an overemphasis on process and targets, resulting in a loss of confidence amongst social workers'.

Brandon and colleagues (2008) stress the importance of effective and accessible supervision. This helps staff put into practice the critical thinking required to understand cases holistically, complete analytical assessments, and weigh up interacting risk and protective factors. This underlines the importance of reflective supervision, an area that will be explored in more detail below.

Supervision processes - a model and processes

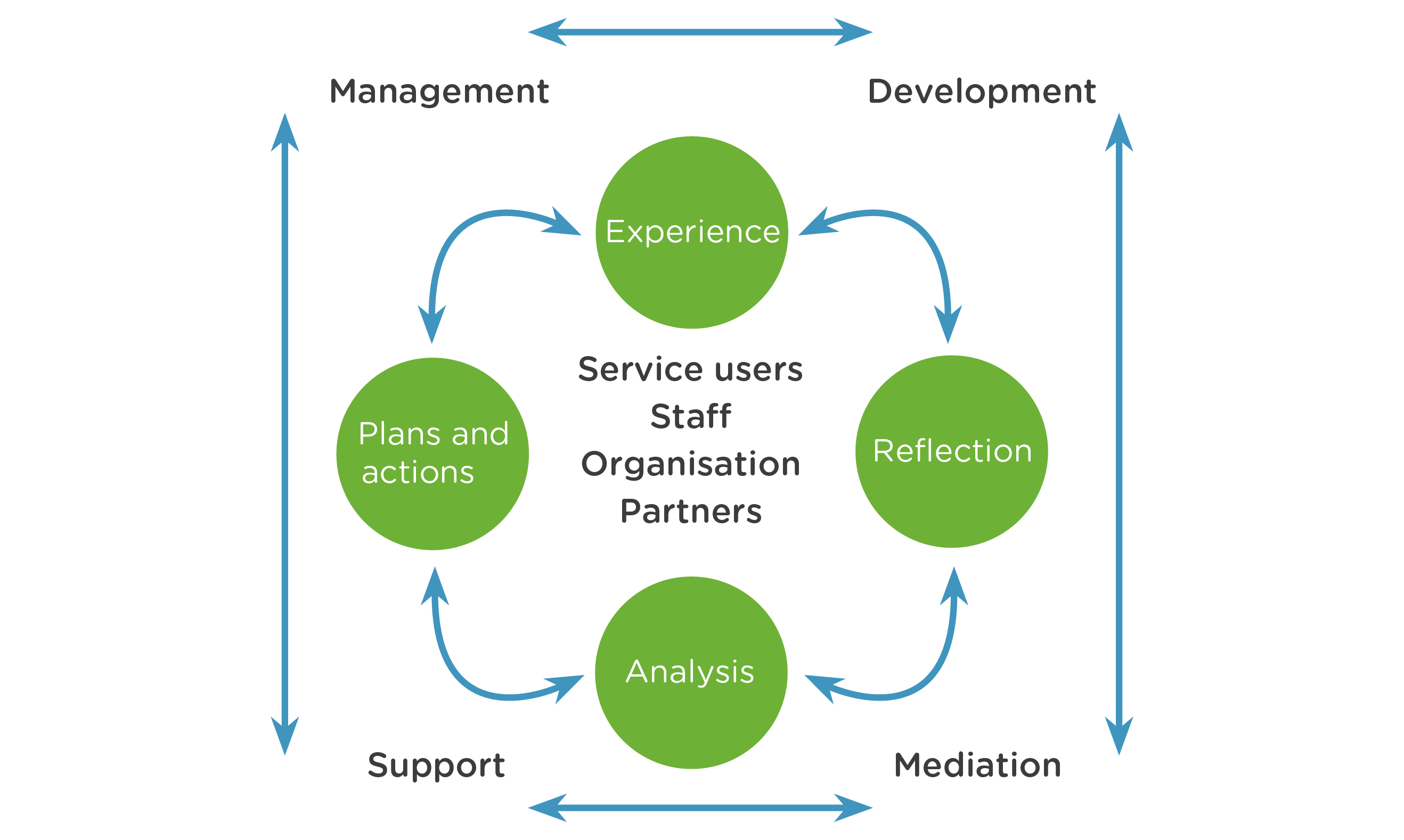

There are many models of supervision, but one that seeks to both promote reflective supervision and to locate it firmly within its organisational context is the 4 x 4 x 4 model.

The model seeks to bring together:

The four stakeholders in supervision

- Service users

- Staff

- The organisation

- Partner organisations

The four functions of supervision

- Management

- Development

- Support

- Mediation

The four elements of the supervisory cycle

- Experience

- Reflection

- Analysis

- Action

As Wonnacott explains, this model moves away from a static, function-based model, and instead promotes a dynamic style of supervision that uses the reflective supervision cycle at the heart of the process. The supervision cycle, 'could be described as the glue that holds the model together' (Wonnacott, 2012, p54) and was developed by Morrison (2005) from earlier work by Kolb (1984) on adult learning theory. According to Kolb, learning involves transferring experience into feelings, knowledge, attitudes, values, behaviours and skills. Morrison (2005) contends that if the cycle is short-circuited in any way there is a danger of getting stuck in unhelpful traps, for example, the 'navel-gazing theorist' who never risks putting their theories to the test or 'paralysis by analysis' where learning is limited by the fear of getting it wrong. Whilst the 4 x 4 x 4 model can perhaps be criticised for underplaying the complexity of the supervisory relationship, in particular the power dynamics involved, it can provide a useful framework for approaching supervision for both the supervisor and supervisee.

Reflective supervision

This section draws heavily on work undertaken by Davys and Beddoe (2010). As has already been identified, the development of a managerialist culture, combined with a tendency to risk aversion, has tended to drive supervision towards a more technical, administrative process, with a desire for 'clean' solutions, which may tend to sideline reflection. According to Schön (1983, p83), many practitioners, 'have become too skilful at techniques of selective inattention, junk categories, and situational control... for them uncertainty is a threat, its admission a sign of weakness'. The reflective learning model (Davys and Beddoe, 2010) turns this on its head, and has a working assumption that supervision is, first and foremost a learning process. Building on Kolb's learning cycle, Davys and Beddoe's (2010) approach follows the: event - exploration - experimentation - event sequence.

Event

The cycle begins with identification of the goal for the issue which the supervisee has placed at the top of the agenda. Through their 'telling' of the event, this stage aims to reconnect with the event without becoming overly immersed to the point of losing focus. Keeping a tight focus clarifies the real issues without the narrative swamping reflection with detail.

Exploration

With a clear goal established, the supervisee can move on to the next stage of the cycle, exploration of the issue. This stage clearly recognises the place of the supervisor's practice wisdom and experience, but also that sharing this prematurely may prevent the supervisee from finding their own solutions (Kadushin, 1992; Cousins, 2010). The task of the supervisor is to create a space for the supervisee to explore possibilities associated with both their own behaviour and the behaviour of others.

Experimentation

Once a decision or understanding has been reached, it is then important that this is tested to establish whether it is possible or realistic. The importance of this stage of the process is that the 'solution' can be examined to ensure that it is sufficiently robust and also that the supervisee has the requisite skills and knowledge in order for any plan to be implemented.

Evaluation

The evaluation stage of the cycle marks the completion of the work and allows for reflection on the process, and in particular whether the supervisee has got what was required with respect to this issue. In short, this model provides the basis for supporting and developing critical practice.

Summary

This model might be criticised for not taking sufficient account of the context within which supervision operates, or for being unrealistic in busy working environments. However, if located within the 4 x 4 x 4 model it allows for supervision to be seen within its organisational context, and a clear theoretical model can be helpful: 'The lack of a clear theoretical model about the nature, influence, and critical elements of effective supervision undermines the ability to drive up standards, training, support, and monitoring of supervisory practice. 'Too often we settle for 'having supervision' rather than having good supervision - a crucial difference' (Supervision: Now or Never, Wonnacott and Morrison, 2010.

Processes in supervision

Supervision does not occur in a vacuum, and is susceptible to a range of external influences. The supervision literature, particularly the strand informed by psychodynamic approaches, explores how the supervisory relationship is influenced by what is going on at other levels of the system. One example of this is mirroring, which Morrison (2005) describes as the unconscious process by which the dynamics of one situation (such as the relationship between the worker and the service user) are reproduced in another relationship (such as that between the worker and supervisor). This process can work in both directions.

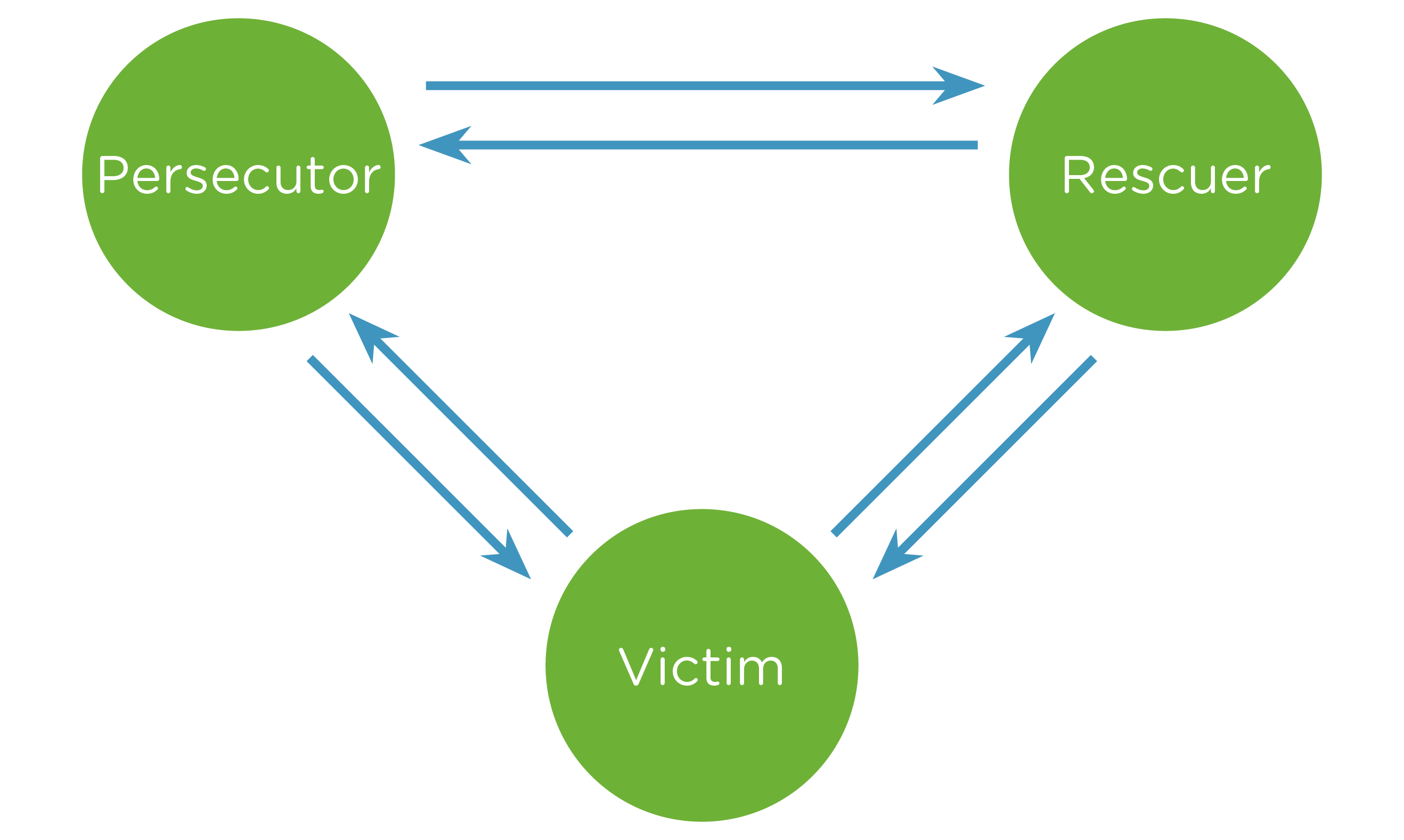

The drama triangle

One of the explanatory devices that is frequently used (Hughes and Pengelly, 1997; Morrison, 2005; Hawkins and Shohet, 2012) is Karpman's (1968) drama triangle, which can seen as playing out in direct practice as well as in supervision.

The terms persecutor, victim and rescuer in this context signify not only what individuals do or have done to them, but more importantly the roles they take up with respect to each other. The persecutor cannot bear to experience their vulnerability, and therefore, seeks to project it onto a victim. In turn a victim cannot tolerate their own hostility and seeks to find someone onto whom this can be projected, namely the persecutor. The victim also abdicates any sense of responsibility, seeking a rescuer onto whom any competence can be projected. A rescuer can bear neither vulnerability nor hostility and sets out to 'save' the victim, a project which is doomed to fail. Davys and Beddoe (2010) argue that the very nature of health and social care leaves practitioners susceptible to an enactment of the drama triangle. Hughes and Pengelly (1997) stress that in caring professions it is particularly the rescuer tendency, with its failure to acknowledge angry feelings that may lead to unsafe practice, and also the risk of creating dependence on supervisees.

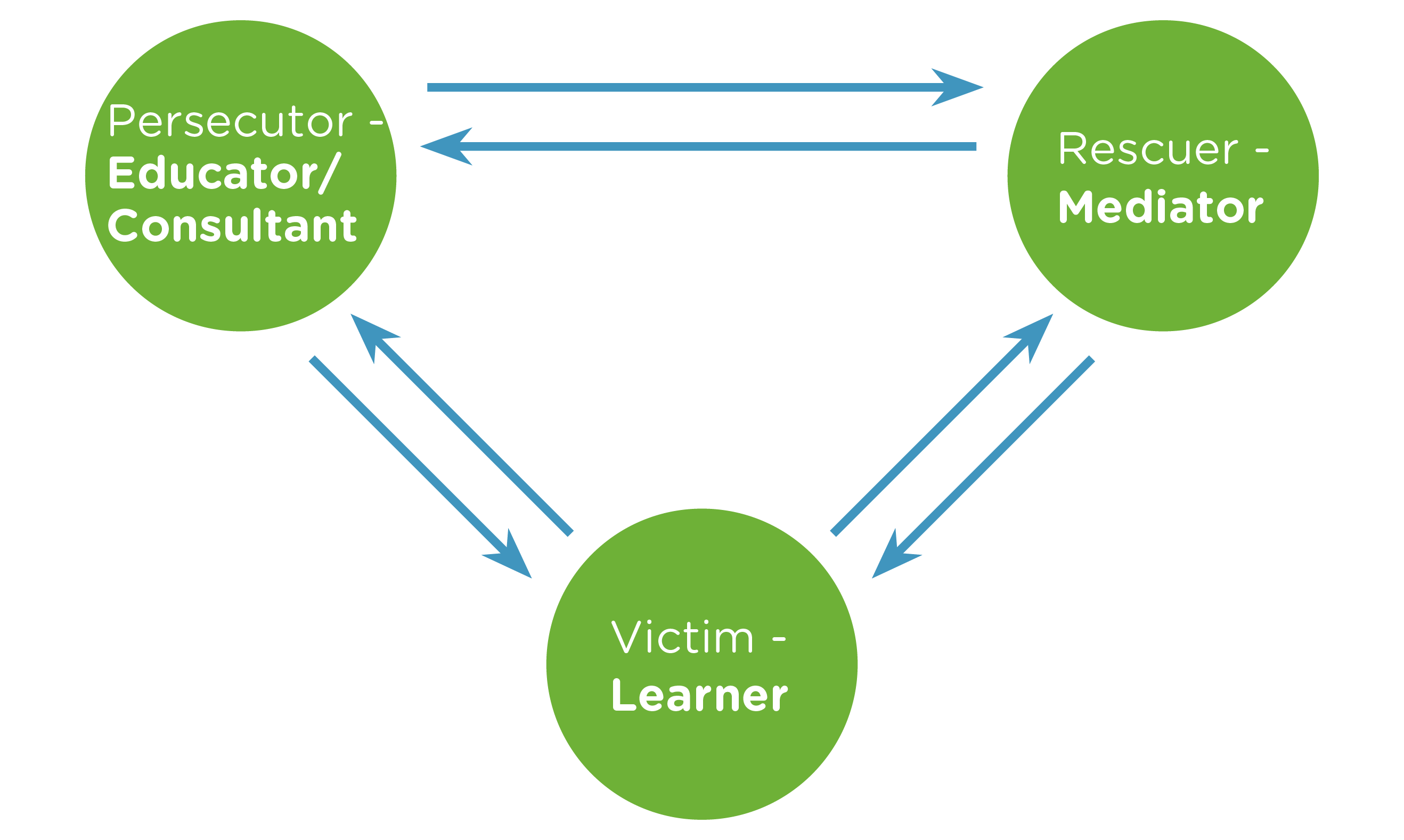

A number of variations have been applied to the drama triangle in recent years. In particular, the empowerment triangle (Cornelius and Faire, 2006, cited in Davys and Beddoe, 2010, p174) identifies alternative roles which can be employed to break the repetitive cycle. For example, if a supervisor finds themself in a persecutor role, the challenge is to become an educator or consultant, for a rescuer the challenge is to become a mediator, and for the victim the challenge is to redefine themselves as a learner.

Supervision games

The complexity of the supervisory relationship may also lead to games being played (Cousins, 2010). Kadushin (1992) outlines a number of games that can be played by both supervisor and supervisee. Examples include the following, with quotes that illustrate the game being played.

Manipulating demand levels

- 'We both know how stupid that procedure is, don't we?'

- 'I know it's my session but you look terrible today'

Redefining the relationship

- 'Let's sort this out over a pint'

- 'Treat me don't beat me'

Reducing the power disparity

- 'Have you ever worked with the elderly?'

- 'So what do you know about it?'

Controlling the situation

- 'I have a little list'

- 'Yes, but...'

Morrison (2005) contends that the greater workload pressures, external insecurity and change, the more likely it is that these defensive processes will arise. Further, that in his words, 'it takes two to tango' in that, even if the supervisor or supervisee has not initiated the game, both parties carry an element of responsibility for its continuance. The way of dealing with games being played is firstly to be able to recognise or name what is happening (Hawkins and Shohet, 2012) and secondly to simply stop playing. This discussion of the dynamics of the supervisory relationship leads into a discussion of the skills involved in supervision.

Skills for supervision

At best, the supervisory task is like a balancing act, managing the tension between.... ensuring agency policies are followed and attending to workers' emotional responses to the work. It can leave a good supervisor feeling pulled in all directions, struggling to manage the balance between feeling stimulated and feeling chronically frustrated and unsupervised (Hughes and Pengelly, 1997, p31).

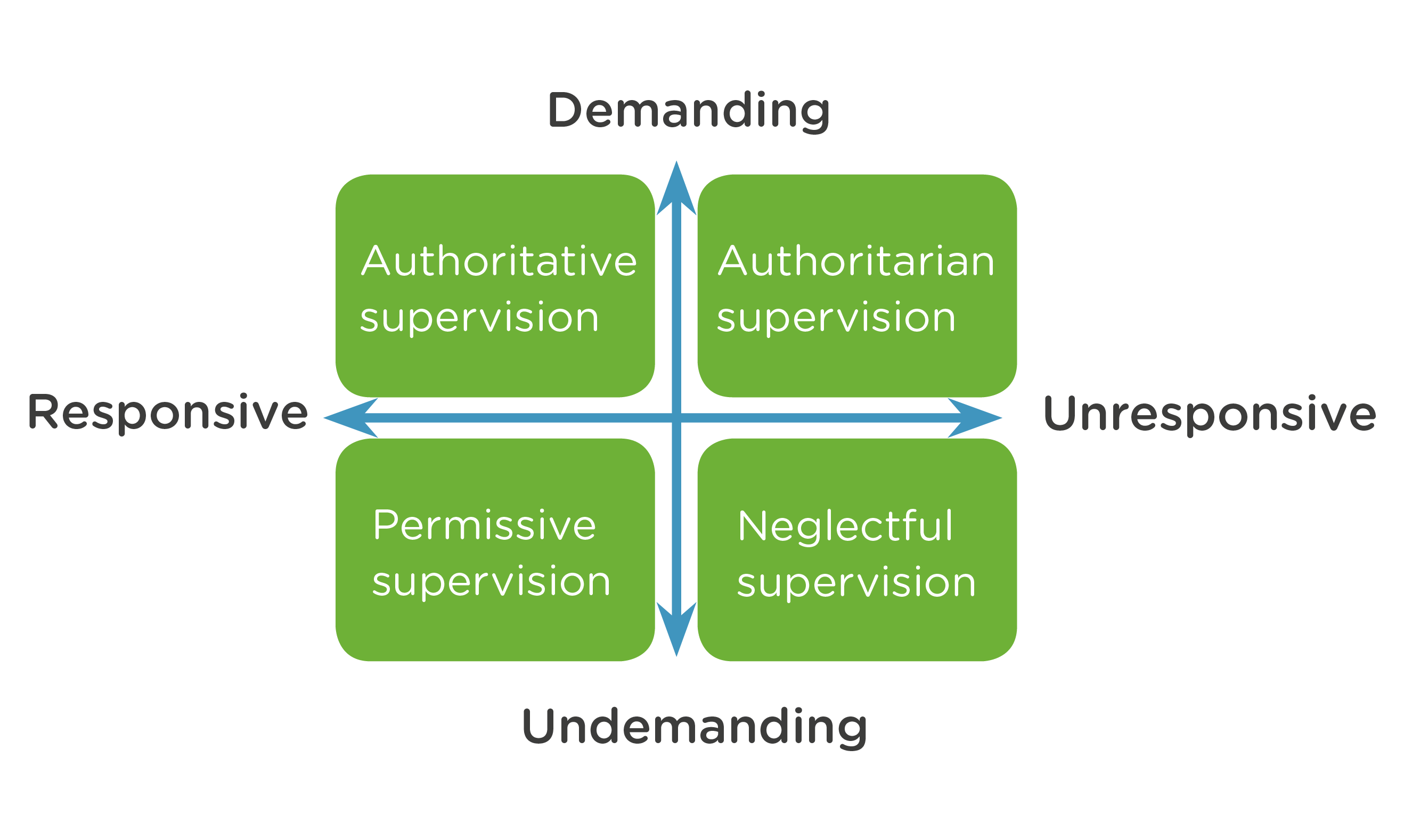

Wonnacott (2012), drawing on previous work on parenting, and criticisms of social work practice for being insufficiently authoritative, for example in the Peter Connelly Serious Case Review (Haringey LCSB, 2009), takes this into the supervision agenda and argues that what is required is a style of supervision that is both demanding and responsive. This is a style that she labels as authoritative, where the supervisor is clear about expected standards and provides a safe environment for supervision, based upon an agreement which makes clear both the negotiable and non-negotiable aspects of supervision. Wonnacott develops this argument, suggesting that failure to remain in the authoritative zone may result in increased worker anxiety and dependence or a lack of focus.

Supervision interventions can be categorized into facilitative, catalytic, conceptual, confrontative and prescriptive (Davys and Beddoe, 2010). Facilitative interventions establish the container within which supervision operates (Isaacs, 1999). Listening is a key skill for the supervisor, 'Just as the professional needs to actively listen to the person they are supporting, the supervisor needs to listen to staff with and provide constructive feedback, listening for positive aspects of practice and identifying things that are going well' (Johnstone and Miller, 2010, p4).

Catalytic interventions aim to promote growth, development and learning. Skills required include the ability to ask open questions, and give feedback, which is a skill in its own right. To be effective, feedback must be clear, owned, regular and balanced (see Davys and Beddoe, 2010 for a more detailed exploration).

Conceptual interventions provide the supervisee with information and knowledge. Caution should be exercised in using these interventions if over-dependence is to be avoided. Bond and Holland (1998, cited in Davys and Beddoe, 2010) offer a useful suggestion in that the more technical the problem the more relevant it is to offer information and advice.

Confrontative interventions, despite the name, are not intended to be adversarial, but are aimed at promoting change and movement. By facing supervisees with previously unrecognised aspects of themselves, discomfort may be created, although when handled well this can be exciting and open up new possibilities for the supervisee.

Finally, prescriptive interventions provide the supervisee with a specific plan of action for a particular situation, generally where there is no option, for example crisis situations, or with a new member of staff. As Davys and Beddoe (2010) caution, prescriptive interventions should be used sparingly, and if they become the norm then it is probable that supervision has slid into performance management. Before concluding this Insight, attention will be paid to the issue of outcomes-focused supervision, before briefly exploring group supervision.

Outcomes-focused supervision

A focus on outcomes, defined as, 'the changes, benefits, learning or other effects that result from what the project or organisation makes, offers or provides' (Miller, 2011, p2) has been emphasised in Scottish policy for several years. For example, Changing lives (Scottish Executive, 2006) stated that less time should be spent on measuring what goes into services and how money has been spent, and that more time should be invested in finding out what difference those services have made (See Miller, 2012 for a fuller exploration of the issues).

Johnston and Miller (2010) contend that there are strong parallels between the role of the practitioner working with the individual to identify and work towards the outcomes important to them, and the role of the supervisor working with the practitioner to identify their strengths and skills, and to be outcomes-focused in their work.

'The primary characteristic of outcomes-focused supervision is maintaining a focus on the intended results of the work, and to use this focus as a way of structuring supervision. Associated with the outcomes are activities that the supervisee, [the] person and others carry out as part of the plan' (Bucknell, 2006, p44).

In an outcomes-focused approach, supervision becomes a forum for clarification and for findings ways of achieving outcomes through identifying opportunities for change. Johnstone and Miller (2010) summarise the shift that is required in terms of three key changes. Firstly, the endpoint shifts from the delivery of the service and a focus on the here and now to exploring the impact of the intervention. Supervision involves a future focus. Secondly, the focus shifts from identifying problems and deficits, with supervision being focused on troubleshooting, to a focus on building on capacities and strengths towards achieving creative solutions. Supervision involves identifying previous strategies which have proved successful. Finally, recording of practice shifts from being a mechanistic, 'tick-box' exercise, to building a picture of the person and towards supporting a clear plan for achieving the desired outcomes. Supervision focuses on achieving the desired outcomes.

Group supervision

The focus of this Insight has been on individual, 1-1 supervision, but there may be circumstances when group supervision is being considered. This may be where there are larger staff groups, for example, in residential or domiciliary care settings, and may involve the group setting in some or all of the responsibilities of supervision (Brown and Bourne, 1996). In some contexts, group supervision might be seen as a viable alternative to individual supervision, particularly for the hard-pressed supervisor. Hawkins and Shohet (2012) caution that ideally group supervision should come about as a positive choice, rather than a forced compromise, and Wonnacott (2012) argues that group supervision should supplement, but never replace individual supervision. Further, the issues identified above about the lack of evidence of the effectiveness of individual supervision transfer to a group setting. Morrison (2005) suggests that there are a number of myths in relation to group supervision, not least that it is a cheaper way of providing supervision, or that it is a process in which all supervisors will necessarily be competent.

These reservations notwithstanding, there are a number of strengths within group supervision. The impact of the group process may foster a sense of team cohesion and reduce the risk of dependence upon an individual supervisor. It can expand the skills and knowledge base of group members and may increase the pool of options and ideas. It may also help the development of more innovative practice. However, there are disadvantages. For the facilitator, these can include being more demanding because of the multiple dynamics, it can confuse boundaries of responsibility and structures or require them to focus on individual and group dynamics at the same time. For the group, it can reflect or amplify dysfunctional team processes, be dominated by a few loud voices, allowing others to hide, or can make it seem less relevant to group members who are at different stages of professional development (Morrison, 2005; Davys and Beddoe, 2010).

Brown and Bourne (1996) stress the importance of getting the basics right, including ensuring transparency with respect to the purpose, focus and key tasks of the group, clarifying the mandate and the authority of the group, defining the boundaries of the group and negotiating the role and authority of the facilitator.

Implications for practice

- Supervision should take place within a culture of learning and development, with space for discretion and autonomy

- There needs to be a balance between surveillance and reflection in the supervisory relationship - a move from dependence to empowerment and growth

- The emotional aspects of the work should be transparently recognised, addressed and supported

- Supervision should be linked directly with practice and to those who use services - relationships matter across all of these roles

- Within supervision, there should be an outcomes focus for all, a focus not only on desired outcomes for the person using services, but also for the practitioner

- Group supervision can be used flexibly to complement, but not replace, individual supervision

- Watch out for game playing - it's easy to assume unhelpful supervisor/supervisee roles and get stuck within these

Conclusion

This Insight has explored some of the literature relevant to supervision within social services, identifying its importance and how dependent its quality and effectiveness is on the organisational context. Whilst the limited evidence base for supervision has been acknowledged, the complexity of the process has been explored and the case made for a reflective approach to supervision. In challenging times, there is a risk of the importance of supervision being downplayed, or of the reflective component being seen as less important that its managerial function. On the contrary, it is argued that effective supervision is even more important.

'Supervision can at very least allow, albeit briefly, the doors to be shut, the noise to be reduced and a quiet space for satisfying professional conversation' (Davys and Beddoe, 2010, p87).

References

- Baines D, Charlesworth S, Turner D et al (2014) Lean social care and worker identity: the role of outcomes, supervision and mission, Critical Social Policy, 34 (4), 433-453

- Beddoe L (2010) Surveillance or reflection: professional supervision in 'the risk society', British Journal of Social Work, 40 (4), 1562-1588

- Brandon M, Belderson P, Warren C et al (2008) The preoccupation with thresholds in cases of child death or serious injury through abuse and neglect, Child Abuse Review, 17 (5), 313-330

- Brown A and Bourne I (1996) The social work supervisor, Buckingham: Open University Press

- Bucknell D (2006) Outcome focused supervision, in H Reid and J Westergaard (eds) Providing support and supervision: an introduction for professionals working with young people, Oxford: Routledge

- Care Council for Wales (2012) Supervising and appraising well: A guide to effective supervision and appraisal for those working in social care, Cardiff: Care Council for Wales

- Carpenter J, Webb C, Bostock L et al (2012) SCIE Research Briefing 43: Effective supervision in social work and social care, London: SCIE

- Carpenter J, Webb C and Bostock L (2013) The surprisingly weak evidence base for supervision: Findings from a systematic review of research in child welfare practice (2000-2012), Child and Youth Services Review, 35 (11),1843-1853

- Cornelius H and Fire S (2006) Everyone can win: responding to conflict constructively, Sydney: Simon and Schuster

- Cousins C (2010) 'Treat me don't beat me'....Exploring supervisory games and their effect on poor performance management, Practice: Social Work in Action, 22 (5), 281-292

- Davys A and Beddoe L (2010) Best Practice in Professional Supervision, London: Jessica Kingsley

- Fleming I and Steen L (2004) Introduction in I Fleming and L Steen (eds) Supervision and clinical psychology: theory, practice and perspectives, 2nd edn, London: Routledge

- Grant S, Sheridan L and Webb S (2014) Evaluation study for the Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC), Readiness for practice of newly qualified social workers, Glasgow Caledonian University/SSSC

- Haringey LCSB (2009) Serious Case Review: Baby Peter, Haringey LCSB

- Hawkins P and Shoet R (2012) Supervision in the helping professions, 4th edn, Maidenhead: Open University Press

- Harvey A and Henderson F (2014) Reflective supervision for child protection practice - reaching beneath the surface, Journal of Social work Practice, Psychotherapeutic Approaches in Health, Welfare and the Community, 28 (3), 343-356

- Hughes L and Olney F (2012) Supervision: the interdependence of professionalexperience and organisational accountability, in A Balfour, M Morgan and C Vincent C (eds), How couple relationships shape our world, London: Karnac Books Ltd

- Hughes L and Pengelly P (1997) Staff supervision in a turbulent environment: managing process and task in front-line services, London: Jessica Kingsley

- Johnstone J and Miller E (2010) Staff support and supervision for outcomes-based working, North Lanarkshire Council/Joint Improvement Team

- Jones M (2004) Supervision, learning and transformative practices, in N Gould and M Baldwin (eds) Social work, critical reflection and the learning organisation, Aldershot: Ashgate

- Kadushin A (1992) Supervision in social work, 3rd edn, New York: ColumbiaUniversity Press

- Karpman S (1968) Script drama analysis, Transactional Analysis Bulletin7 (26), 39-43

- Kolb D (1984) Experiential learning, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall

- Laming H (2009) The protection of children in England, London: The Stationery Office

- Lawlor D (2013) A transformation programme for children's social caremanagers using an interactional and reflective supervision model to develop supervision skills, Journal of Social Work Practice: Psychotherapeutic Approaches in Health, Welfare and the Community, 27 (2), 177-189

- Local Government Association (2014) The standards for employers of social workers in England, London: Local Government Association

- Malahleka B (1995) 'Interface or interference?' Professional Social Work, July 1995, 10-11

- Manthorpe J, Moriarty J, Hussein S et al (2015) Content and purpose of supervision in social work practice in England: Views of newly qualified social workers, managers and directors, British Journal of Social Work, 45 (1), 52-68

- Middleman R and Rhodes G (1980) Teaching the practice of supervision, Journal of Education for Social Work, 16 (3), 51-59

- Miller E (2012) Measuring personal outcomes: Challenges and strategies, Glasgow: Iriss

- Morrison T (2005) Staff supervision in social care, 3rd edn, Brighton: Pavilion Publishing

- Morrison T and Wonnacott J (2010) Supervision: Now or never: Reclaiming reflective supervision in social work http://www.in-trac.co.uk/supervision-now-or-never/

- Munro E (2010) The Munro Review of Child Protection: Interim report-The Child's

- Journey, London: Department for Education

- Munro E (2011) The Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report - A child-centred system, London: Department for Education

- Noble C and Irwin J (2009) Social work supervision: An exploration of the current challenges in a rapidly changing social, economic and political environment, Journal of Social Work, 9 (3), 345-358

- Peach J and Horner N (2007) Using supervision: Support or surveillance?, In M Lymbery M and K Postle (eds) Social work: a companion for learning, London: Sage

- Schon D (1983) The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action, New York: Basic Books

- Social Care Institute for Excellence (2013) Practice enquiry into supervision in a variety of adult care settings where there are health and social care practitioners working together, London, SCIE

- Vincent S and Petch A (2012) Audit and analysis of Significant Case Reviews, Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- Wonnacott J (2012) Mastering social work supervision, London: Jessica Kingsley

- Iriss Insights

Acknowledgements

This Insight was reviewed by Helen Allbutt and colleagues from NHS Education for Scotland, colleagues from Scottish Government, Frances Patterson (University of Stirling and Gillian Muir (Clackmannanshire and Stirling Council Social Services), Emma Miller (University of Strathclyde) and Keir McKechnie (Includem). Iriss would like to thank reviewers for taking the time to reflect and comment on this Insight.