Key Points

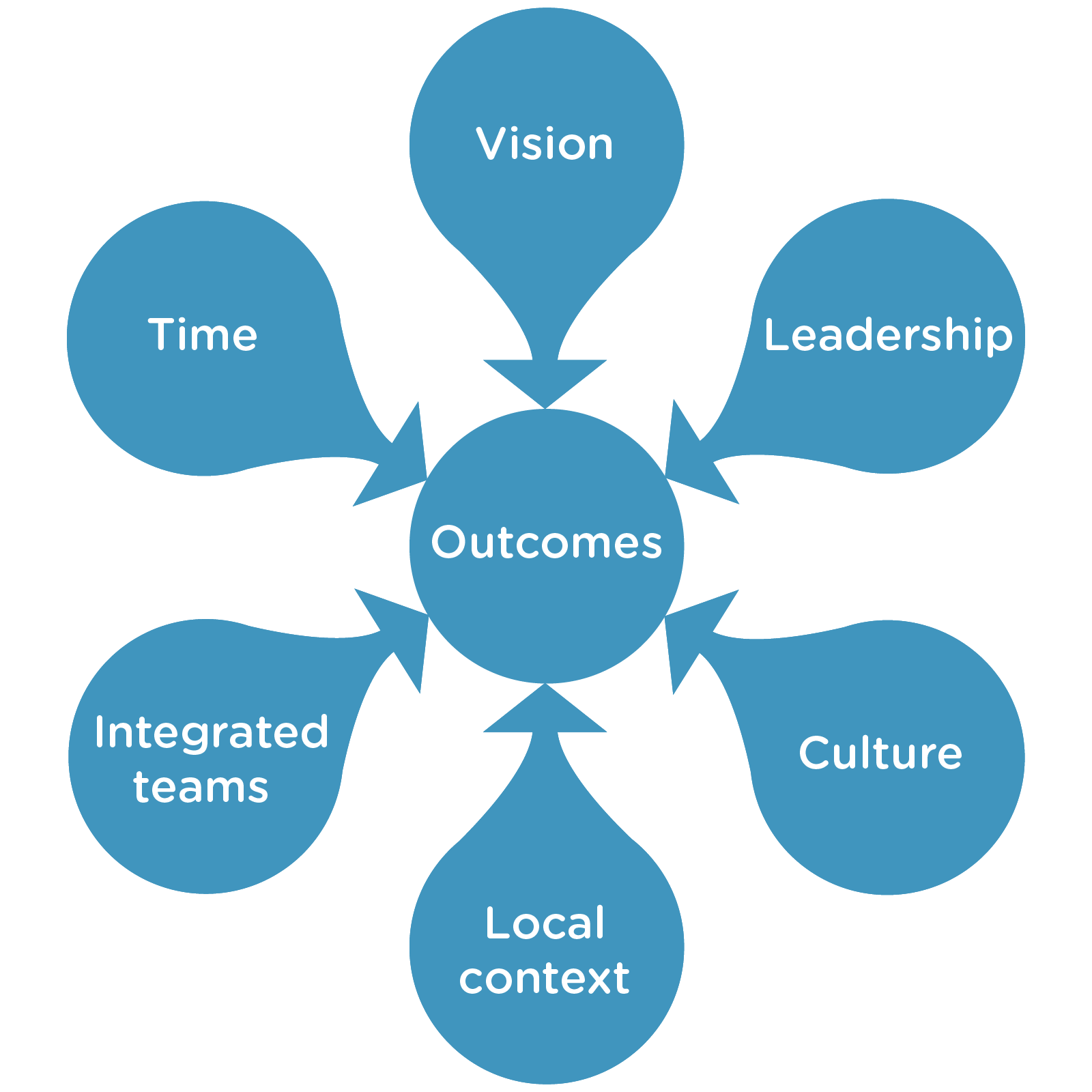

- The achievement of personal outcomes for individuals should be the focus of integrated care and support.

- Six dimensions are key to the delivery of integrated care and support: vision; leadership; culture; local context; integrated teams; and time. Factors that facilitate delivery of each of these dimensions are highlighted.

- Transformational and distributed leadership led by a vision that is shared and maintained is essential.

- Individuals working as 'boundary spanners' are valuable for reaching across organisational boundaries.

- The drive to deliver integrated care and support should lead to the emergence of new cultural identities rather than forcing together the old.

- The delivery of integrated care and support must be responsive to local assets and partnerships.

- There is no single prescription for an integrated team structure or management but clear lines of accountability are essential.

- Timescales of several years are required to develop and embrace integration.

This Insight was written by Alison Petch (Iriss)

Introduction

This document is based on a report prepared for ADSW at the time of the Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Bill (Petch, 2013) and seeks to distill key evidence to assist health and social care partnerships in Scotland in their delivery of integrated care and support. It works from the premise that structural change by itself does not deliver the improved outcomes sought for service users and communities, unless equal or greater attention is paid to a range of other key factors (Ham and Walsh, 2013; Ham et al, 2013).

These other factors can be grouped using the categories in the diagram below which summarises the conclusions from an earlier evidence review (Petch, 2011; Iriss 2012a).

Many of the dimensions are inter-related; those seeking to deliver successful integration have to chart a path which both draws on successful examples from elsewhere and adapts to the specific local context. Given the lack of structural determinism, the directives should be equally applicable whether the approach adopted be the 'body corporate' or lead agency model.

Outcomes

Discussion of outcomes and of outcomes-focused approaches has come to the fore over the last decade. As with the term 'integration' in the past, however, there is the tendency to compound different meanings and the potential therefore for people to be talking at cross purposes. Most particularly there is the need to distinguish individual (personal) outcomes from service or organisational outcomes, and local from national outcomes (Iriss, 2013b).

The suite of outcome measures proposed for Health and Social Care Integration (REF) shows a significant shift from the past tendency to see outputs and performance measures masquerading as outcomes. The focus should not be on delayed discharge or bed occupancy figures per se but on delivering positive experiences for the individual and ensuring quality of life.

The Scottish Government's consultation paper stressed (3.2) that 'The underlying principle of these proposals is to provide national leadership in relation to what is required - the outcomes that must be delivered - and to leave to local determination how best to achieve those outcomes - the delivery mechanisms that will best suit different local needs'. From the perspective of the evidence this is to be welcomed; the challenge for partnerships is to maintain this focus rather than be dragged into preoccupation with the detail of governance and structures.

Both Beresford and Branfield (2006) and National Voices (2011) argue the case for integrated working to deliver the outcomes that are important to individuals. This recognises that much of earlier discussion of partnership working has focused on the process of working together rather than on the impact on individuals accessing support (Dowling et al, 2004). In Scotland the development of Talking Points has generated considerable discussion and exploration of outcomes at the individual level (Miller, 2011; Cook and Miller, 2012; Iriss, 2012b; Miller and Daly, 2013). To date this discussion tends to have been led by social care; the challenge of leading a personal outcomes approach in integrated working is explored in Iriss (2013). The cycle needs to move from outcomes-focused assessment, planning and review with the individual, to aggregation of outcomes across individuals, to outcomes-based commissioning.

There is particularly close interaction between the dimensions of vision, outcomes and leadership. Outcomes should form a major component of the vision; likewise strong leadership is required to transform the focus from one on inputs and outputs to the more challenging outcomes. The evidence suggests that there is a direct correlation between leadership and positive outcomes (Bogg, 2011).

Delivery on the dimension of outcomes requires:

- Commitment to the achievement of personal outcomes

- Understanding of the different layers of outcomes

- Adoption of a holistic perspective embracing health social care, and housing outcomes

- Ability to identify outcomes of different types and to distinguish them from outputs

- Willingness to negotiate across different professional priorities in respect of outcomes

- Demonstration of the differences that have been made in terms of outcomes

Vision

Those who embark on the delivery of integrated care and support need to be led by a vision; there needs to be a sense of purpose and a logic for required action and change. Integration cannot be an end in itself; it must be for a purpose. Successful delivery of integrated care and support requires a commitment to and a belief in a goal to be achieved. Those working to a vision need to be proactive rather than reactive and, as detailed below, leadership is required to achieve the vision. The vision needs to be communicated, shared, reinforced and embedded. The experience of Torbay as an early adopter of integrated working has been widely reported (Thistlethwaite, 2011); their driver of 'getting it right for Mrs Smith' provided the enduring vision placed at the heart of the transformation.

Maintaining fidelity is essential to avoid drift. Generally, a vision works best when it is developed in partnership with the range of stakeholders in the local community and can be articulated both at strategic level and to frontline staff.

Delivery on the dimension of vision requires:

- A vision that can be operationalised in a set of aspirational but achievable goals

- A vision that has at its core the delivery of outcomes for the individual

- Consistent communication of the vision to a wide range of stakeholders

- Demonstration of 'quick wins' to maintain buy-in

Leadership

It has become commonplace to emphasise the importance of leadership for the delivery of integrated care and support: 'in times of organizational transition... transformational leadership takes a central role in setting the vision and the outline of the organization for the future' (Dickinson et al, 2007). Leadership is more than management; it suggests a capacity to inspire, motivate and engage, to challenge embedded preconceptions and power dynamics and to negotiate competing understandings and agendas.

Traditional notions of 'heroic leadership' as dynamic, decisive, authoritarian and competitive are not well suited to the environment of integrated care and support. Increasingly it has been recognised that the complex world of integrated working requires a different approach. This requires sophisticated skills of negotiation and consultation to enable collaborative agreement on the direction to be taken and to foster collective decision-making. Leaders need to be supportive of innovation, have an awareness and understanding of the complexity of integrated working, and need to be alert to the perspectives of all the different stakeholders involved. These new models of leadership have moved away from a focus on the 'heroic individual' to a more inclusive and organic approach. This has led to models of leadership based not only on the individual qualities of the leader but on how they enable the whole system to support innovation and work together as a team.

Transformational or dispersed leadership is characterised by a desire to create a sense of collective identity and ownership. Through acting as a role model, leaders seek to enhance people's motivation, morale and performance. Such an approach to leadership is designed to steer the development and delivery of a vision, to empower users and staff, to foster a strengths-based approach, to support positive risk taking, to encourage staff to reflect and challenge, and to encourage creativity. It requires a clear accountability framework, transparent governance, robust supervision, acknowledgement of the range of skills and experience in the workforce, and targeted professional development (Bogg, 2011).

Effective leaders are usually characterised by their sustained long-term commitment, enthusiasm and involvement in integrated care locally, and trust and respect given by their peers that has built up over time Leaders for integrated care and support need to embrace change and take the initiative rather than adopting a fortress mentality focusing on their own organisations. Leaders need the skills and strategies necessary to understand, influence and lead the local agenda in the design, commissioning and delivery of integrated care and support. A recent case study by Williams (2012) highlights four components of leadership considered key to facilitating integrated delivery: promoting common purpose, developing a collaborative culture, facilitating multi-disciplinary teamwork, and developing learning and knowledge management strategies.

An important role in the context of integrated working is what has been termed the 'boundary spanner' (Williams, 2011), key individuals who have a pivotal role across organisational boundaries. A range of different elements of this role can be distinguished:

- the leader, using skills such as brokerage, facilitation, negotiation, co-ordinated project management and cross-fertilisation

- the entrepreneur and innovator, making things happen through creative thinking

- the interpreter/communicator, able to understand the perspectives of multiple partners and developing trust between them.

- the 'reticulist' making connections, skilled in bringing people together across boundaries and using interpersonal skills and effective networking in negotiation

It is generally acknowledged that certain personality types and personal attributes are prerequisite for the role - 'personable, respectful, reliable, tolerant, diplomatic, caring and committed'. Moreover the challenges inherent in the role are acknowledged, with the need to manage ambiguity and tension.

Delivery on the dimension of leadership requires:

- commitment and belief in a shared vision

- a focus on delivery on individual and organisational outcomes

- an ability to look outward and to transcend professional identities

- an ability to inspire and engage followers across the partnership

- support for creativity and positive risk-taking

- promotion of leadership at different levels across the partnership

- identification and nurturing of boundary spanners

Culture

Much of the achievement of integrated care and support is dependent on successful culture change. Both professions and organisations are likely to have developed particular cultures which help to shape their identity and foster allegiance. Over time, as an individual settles into their role, they are likely to acquire tacit knowledge and implicit ways of working that both derive from and help to bolster this cultural identity. The strengths of such identity can become problematic when individuals and organisations are seeking to work more closely together. A new cultural identity needs to be fostered which transcends the traits of particular professions or individuals and provides the most effective basis for the delivery of integrated provision and the achievement of organisational and individual outcomes. 'You know you've cracked it when there's only one kettle in the kitchen' (Sullivan and Williams, 2012). Williams (2012) argues that the transfer of tacit knowledge between professional groups - which should be interpreted as all staff groups - is key to integration.

Reference to 'culture' is a common feature of discussion of integrated working. It reflects a sense of shared values, beliefs and assumptions, the essence of 'how we do things around here' (Iriss, 2012c). Schein suggested that there are three sources of culture. These are: the beliefs, values and assumptions of the founders of the organisation; the learning experiences of group members as the organisation evolves; and the fresh beliefs, values and assumptions brought in by new members (Dickinson et al, 2007). Moreover Schein identified culture as having three layers - cultural artefacts eg dress codes; espoused values eg mission statements; and basic assumptions eg ways to behave. All three of these dimensions are relevant to the cultural change necessary for effective health and social care integration, with a particular need not to overlook the detail of the everyday encounter in the workplace.

The development of integrated care and support requires an acknowledgement of the need for cultural change. Seeking to retain existing cultures inevitably leads to a fight for dominance and a concern that the culture of one or other of the partners in the collaboration will win out. The drive to deliver integrated care and support should lead to the emergence of a new cultural identity, one committed to the integrated working agenda. The notion of organisational 'sense making' is introduced by Dickinson et al (2007) in their discussion of the ways in which culture can be both an aspiration and a barrier for partnership working. This suggests that people create their understandings of organisations from their interpretations of what they see and experience rather than from structures or systems. Organisational goals and strategies, for example, are not 'things' out there but reflect people's ways of thinking; during transition and change this understanding needs to be challenged and a new narrative created.

From their case study of the establishment of a Care Trust, Dickinson and her colleagues suggest that in the attempt to keep the best of both existing cultures, to maintain familiarity and avoid 'rocking the boat', the opportunity for innovation may have been stifled. Consensus was seen as important and an element of 'collaborative inertia' ensued. The opportunity to engage with wider partners, for example the third sector, was also missed.

Peck and his colleagues (2001) highlight a question critical to the discussion of culture change and the development of integrated care and support:

'Is the desired result one entirely new culture, albeit comprised of elements taken from all the current professional cultures - the melting pot approach to culture? Or is the desired result the enhancement of the current professional cultures by the addition of mutual understanding and respect - the orange juice with added vitamin 'c' approach to culture?' (p325)

They also illustrate the extent to which culture is maintained and revealed through language, images and themes, through the pattern of interactions, and in the rituals of daily routines.

Culture change is the focus of Iriss Insight 17 (Iriss, 2012c) and the associated storyboard1. As part of a useful summary of culture change, this highlights a number of features that enable culture change: a clear vision; identifying stories; effectively communicating the vision; development of a strategy; identifying quick wins; measuring indicators of success; and developing leadership. Elements to be avoided include short-term budgets, the risk averseness associated with hierarchical control, and a lack of operational leadership skills. This emphasises again the essential linkages across the different dimensions presented here.

Delivery on the dimension of culture requires:

- acknowledgement of the differing cultures of different organisations, professions and individuals

- awareness of the need to facilitate, promote and foster the development of a fresh emerging culture

- effective communication of the emerging cultural identity

- leadership that encourages positive risk-taking and rewards innovation and engagement with unfamiliar activities or approaches

- addressing issues for front-line staff

- navigating and overcoming barriers of communication and perception

Integrated teams and other ways of working

The delivery of integrated care and support at the local level is achieved through a variety of teams and other structures. This section will explore the features that are more likely to facilitate the delivery of integrated support. As with other dimensions there cannot be a single prescription and the model for delivery will need to be configured to local circumstances: 'Despite the volume of research dedicated to teams, there is no single prescription for an effective team' (Jelphs and Dickinson, 2008:32).

There is a fairly well-developed evidence base on what makes for effective integrated team working (Maslin-Prothero and Bennion, 2010). The work of Ovretveit and colleagues (1993; 1997) has endured over many years. The continuum identified at organisational level, from relative autonomy through partnership to structural integration, has a parallel in terms of different degrees of integration at the team level. At one end there may be a network of associated professionals; at the other a fully managed multi-disciplinary and multi-agency team. Ovretveit suggests interprofessional teams can be described in terms of four key dimensions: the degree of integration, team membership, team process issues (who does what during the user journey), and team management.

In terms of team process six models were identified by Ovretveit and can still commonly be found:

- Parallel-pathway team: the pattern of most network teams where each profession has their own care pathway for service users

- Allocation or 'post-box' team: referrals are allocated at a team meeting and then worked with by the single professional

- Reception-and-allocation team: there is a short-term response at the reception stage prior to the team meeting allocation

- Reception-assessment-allocation team: this includes two allocation stages, one for assessment and one for longer-term work

- Reception-assessment-allocation-review team: a review stage is built in at which the team member reports on progress to the team

- Hybrid-parallel-pathway team: a mix of different elements from the above

With respect to multidisciplinary team management there are five broad types of management structure for formal teams:

- Profession-managed: practitioners are managed by managers from their own profession, most common in network teams

- Single-manager: all team members, regardless of profession, managed by a single manager

- Joint management: a mix of team co-ordinator and professional superior who agree a division of roles

- Team manager-contracted: a model whereby a team manager with a budget contracts in team members who retain their profession managers

- Hybrid management: a mixed management structure with the team manager managing core staff, co-ordinating others under a joint management agreement and contracting-in others

There is no evidence to suggest one form of team management is inherently superior; however it is essential that there is a structure and process for team accountability. Excessive dependence on management by individual professions can lead to a lack of cohesion and an absence of team identity. Teams need to be more than the sum of the individual members. Successful teams require the development of a shared team ethos for working with people, professional respect for other members of the team, and opportunities for team learning. There also needs to be an understanding amongst individual members of each professional group as to what are their own unique professional skills and where there can be flexibility around common skills.

The challenge of maintaining essential aspects of professional identity whilst at the same time relaxing into more inclusive identities is a key issue that has to be navigated in the delivery of integrated care and support. In arguing the need for a 'fundamental change in thinking', Hubbard and Themessl-Huber (2005) highlight the constraints that can be imposed by individuals' allegiances to traditional roles and boundaries - 'old habits die hard'. Access routes for services can also constrain integrated working. Ideally the delivery of integrated care and support needs to become the core focus of an individual's professional identity.

The Integrated Care Network (2008) concludes that multi-disciplinary teams or managed networks should: have a single manager (or co-ordinator); include a mix of staff appropriate to the role of the team; have a single point of access, single assessment process, record system, administration; have access to a pooled, delegated budget; support individuals in commissioning individual care programmes; and link easily and coherently to universal services such as GPs and schools and to secondary care such as hospitals.

Co-location is an important factor in facilitating effective joint working (Freeman and Peck, 2006; Hudson, 2007). Staff tend to have better working relationships including greater mutual understanding and better communication. It should be noted however that co-location alone is not necessarily sufficient; commitment to work towards shared objectives can be key (Warne et al, 2007). This was underlined by the experience in several of the Care Trusts where social work, although co-located, remained a separate division, a barrier to the perception of integration.

Delivery on the dimension of integrated teams and other ways of working requires:

- clarity of team or network structure

- clear lines of management responsibility

- a manager with final accountability

- work to develop a common identity and sense of purpose

- mechanisms for resolving areas of uncertainty and/or conflict

Local context

As demonstrated by the 'early adopters' of integrated working in England, there is no 'one size fits all' design. Development of integrated care and support needs to be sensitive and responsive to the particular geographic, financial, policy and professional features of the particular locality. At the same time, however, there needs to be a considered judgement that reaches an appropriate balance between excessive fragmentation at the local level and standardisation which is insufficiently responsive to local characteristics (Hubbard and Themessl-Huber, 2005).

The influence of local factors can be frustrating for those seeking to replicate what has been successful elsewhere. Direct import of a particular configuration is rarely possible; what is required is an understanding of the local context and adjustment to it. Increasingly, consideration is being given to understanding the strengths (assets) within a locality and to adopting a total place perspective. Such an understanding is closely linked to the development of the vision and to the presence of the leadership detailed above. Effective engagement of the third and community sectors can be key. Co-terminosity is likely to be a facilitating factor, although each local authority area may be divided into two or more localities for locality planning purposes.

>Effective communication and exchange of information at the local level is an essential prerequisite for the delivery of integrated care and support. Mechanisms can include managed care networks, journal clubs, casework meetings, attached practitioners or a range of informal networks. Fundamental however is common access to the records for an individual, in many areas one of the 'wicked issues' that appears to defy an integrated IT solution. Current IT capability for shared electronic databases would suggest this barrier is professional rather than technical. Hubbard and Themessl-Huber suggest, however, that sharing existing knowledge is not sufficient: 'joint working is not simply about health and social care professionals sharing and transferring knowledge about patients and services, it is also about creating new ways of thinking and models of care bespoke to joint working' (2005: 382). At the local level, the primary concern of staff involved in change is to understand their role in the new arrangements and to determine how this fits with their current professional identities and their own professional development.

Delivery on the dimension of local context requires:

- In-depth understanding of the strengths and needs of the locality

- Flexibility

- Co-production

- A 'can-do' approach

- Good communication

- Robust data sharing

- Effective leadership at all levels

Timescales

The timescales for achieving robust change are a key challenge for the delivery of integration. The political imperative is for visible change and a 'solution' to the delays and disjunctures that have driven legislative change. Embedding whole scale cultural change on the other hand is likely to take a minimum of three years and may take much longer (Iriss, 2012c).

Delivering for Mrs Smith in Torbay evolved over a ten year period, based initially in a handful of GP surgeries (Thistlethwaite, 2011). Hultberg et al (2005), in their study of interdisciplinary collaboration in rehabilitation services in Sweden, similarly stress the time that is required for any formal partnership agreement to be translated into changes in attitudes, culture and ways of working amongst front-line staff. From their work with the 16 Integrated Care pilots funded in England by the Department of Health for a two year period, Ling et al (2012) suggest that too much was expected of the pilots within such a timescale. They also conclude that two years of initial development and a year of live working is required for significant change. They also flag that the strategies required for early quick wins may require modification to achieve sustained change.

Delivery on the dimension of timescales requires:

- realistic appraisal of timescales

- communication of timescales to stakeholders including elected members and board members

- recognition of the need for continual revision and modification of implementation strategies

Conclusions

The evidence base which has accumulated over the last decade and more offers a range of robust indications of the most effective ways of achieving integrated care and support (Stewart et al, 2003; Cameron et al, 2012; Glasby, 2012; CfWI, 2013). The current legislation offers an opportunity to draw on this evidence in the course of implementation. Much of the debate has tended to focus on the intricacies of structures and governance arrangements whereas, as reinforced by the evidence reiterated here, the factors likely to have greater impact on the delivery of acceptable outcomes for individuals are those which focus on leadership, on vision, and on context.

References

- Beresford P and Branfield F (2006) Developing inclusive partnerships: user-defined outcomes, networking and knowledge - a case study, Health and Social Care in the Community, 14 (5), 436-444

- Bogg D (2011) Leadership for social care outcomes in mental health provision, International Journal of Leadership in Public Services, 7 (1), 32-47

- Cameron A, Lart R, Bostock L and Coomber C (2012) Factors that promote and hinder joint and integrated working between health and social care services, Research Briefing 41, London: SCIE

- Centre for Workforce Intelligence (CfWI) (2013) Think integration, think workforce: three steps to workforce integration, CfWI/IPC

- Cook A and Miller E (2012) Talking Points Personal Outcomes Approach: Practical guide, Edinburgh: Joint Improvement Team

- Dickinson H, Peck E and Davidson D (2007) Opportunity seized or missed? A case study of leadership and organisational change in the creation of a Care Trust, Journal of Interprofessional Care, 21 (5), 503-513

- Dowling B, Powell M and Glendinning C (2004) Conceptualising successful partnerships, Health and Social Care in the Community, 12 (4), 309-317

- Freeman T and Peck E (2006) Evaluating partnerships: a case study of integrated specialist mental health services, Health and Social Care in the Community, 14 (5), 408-417

- Glasby J (2012) 'We have to stop meeting like this': what works in health and local government partnerships, Policy Paper 13, Birmingham: Health Services Management Centre

- Ham C and Walsh N (2013) Making integrated care happen at scale and pace, London: King's Fund

- Ham C, Heenan D, Longley M and Steel D (2013) Integrated care in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales: Lessons for England, London: King's Fund

- Hubbard G and Themessl-Huber M (2005) Professional perceptions of joint working in primary care and social care services for older people in Scotland, Journal of Interprofessional Care, 14 (3), 8-18

- Hudson B (2007) Pessimism and optimism in inter-professional working: the Sedgefield Integrated Team, Journal of Interprofessional Care, 21 (1), 3-15

- Hultberg E-L, Lonnroth K and Allebeck P (2005) Interdisciplinary collaboration between primary care, social insurance and social services in the rehabilitation of people with muscoskeletal disorder: effects on self-rated health and physical performance, Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19, 115-124

- Integrated Care Network (2008) A practical guide to integrated working, London: Care Services Improvement Partnership

- Iriss (2012a) Measuring personal outcomes: Challenges and strategies, Iriss Insights No 12

- Iriss (2012b) Integration of health and social care, Iriss Insights No 14

- Iriss (2012c) Culture change in the public sector, Iriss Insights No 17

- Iriss (2013) Leading for Outcomes: Integrated Working

- Jelphs K and Dickinson H (2008) Working in Teams, Bristol: Policy Press

- Ling T, Brereton L, Conklin A et al (2012) Barriers and facilitators to integrating care: experiences from the English Integrated Care Pilots, International Journal of Integrated Care, 12, July

- Maslin-Prothero S and Bennion A (2010) Integrated team working: a literature review, International Journal of Integrated Care, April

- Miller E (2011) Good conversations: Assessment and planning as the building blocks of an outcomes approach, Edinburgh: Joint Improvement Team

- Miller E and Daly E (2013) Understanding and Measuring Outcomes: the role of qualitative data

- National Voices (2011) Integrated care: what do patients, service users and carers want? (PDF)

- Øvretveit J (1993) Coordinating Community Care, Buckingham: Open University Press

- Øvretveit J, Mathias P and Thompson T (1997) Interprofessional Working for Health and Social Care, Basingstoke: Macmillan

- Peck E, Towell D and Gulliver P (2001) The meanings of 'culture' in health and social care: a case study of the combined Trust in Somerset, Journal of Interprofessional Care, 15 (4), 319-327

- Petch A (2011) An evidence base for the delivery of adult services, Report commissioned by ADSW

- Stewart A, Petch A and Curtice L (2003) Moving towards integrated working in health and social care in Scotland: from maze to matrix, Journal of Interprofessional Care, 17 (4), 335-350

- Sullivan H and Williams P (2012) Whose kettle? Exploring the role of objects in managing and mediating the boundaries of integration in health and social care, Journal of Health Organization and Management, 26 (6), 697-712

- Thistlethwaite P (2011) Integrating health and social care in Torbay: Improving care for Mrs Smith, London: King's Fund

- Warne T, McAndrew S, King M and Holland K (2007) Learning to listen to the organisational rhetoric of primary health and social care integration, Nurse Education Today, 27, 947-954

- Williams P (2011) The life and times of the boundary spanner, Journal of Integrated Care, 19 (3), 26-33

- Williams P (2012) Integration of health and social care: a case of learning and knowledge, Health and Social Care in the Community, 20 (5), 550-560