Innovation is not a practice reserved for ‘the creative’ or ‘the experts’. You innovate all the time…

Hello innovator!

Innovation has got quite a reputation. It is fresh, bold and awe-inspiring. It is also daunting, difficult and prone to failure. To many it appears elitist, reserved for those who are brave, creative and can afford to make mistakes. Innovation's place in social services is often questioned. How can you take chances with anything that directly impacts on people's lives?

However, innovation is not a practice reserved for 'the creative' or 'the experts'. You innovate all the time. On a daily basis you find ways to overcome challenges and work around problems. You use your experience and borrow ideas from other people or approaches; you combine these into a new configuration, within a new context, so that something is changed for the better. You create new ideas and make them real. You might need expert advice on scaling up a new initiative and creative assistance on how to present it, but being the inventor of an original idea is everybody's business.

For the last 50,000 years the human brain has been capable of 'blending': combining notions, whether compatible or incompatible in their original states, to create new things and concepts (Turner, 2014). For generations people have achieved breakthrough inventions because of a unique and inherent collection of human traits:

- Curiosity

- Interest

- Ability to learn

- Ability to teach

Our experiences of the world continuously affect our decisions and actions. What we can conceptualise, and try out, may improve or amend our approach. Voila! - that's innovation and advancement.

Blending

New ideas come from unlimited sources and opportunities. Often a change in environment or parameters can lead to a change in how we engage with and within our surroundings. Adapting to these new rules allows our minds to make new sense of what we do and what we make use of.

Combining existing ideas to create a new idea often mimics natural selection: it results in a hybrid, which, when it is successful, is stronger and more resistant.

The power of combining ideas has been excellently demonstrated by Kirby Ferguson in his series of videos 'Everything is a remix'. He shows that creativity 'happens by applying ordinary tools and thought to existing materials' and that 'everything we make is a remake of existing creations, our lives, and the lives of others' (Ferguson, 2012).

Everything is a Remix Part 1 from Kirby Ferguson on Vimeo.

Geoff Mulgan of Nesta also argues that drawing on a range of inputs external to your usual area of work helps generate ideas. The process of creating ideas (ideation) can be made easier by using social design tools that specify easily taken steps which will help generate more radical ideas (Mulgan, 2014).

"All mankind is of one author, and is one volume; when one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language; and every chapter must be so translated."

- John Donne

We all have a hand in the advancement of the world. On an individual level we may never know what our inputs are; nevertheless, we are each other's inspiration. No one really owns an idea. A person can have their name attributed to an idea but, with time, this will be reduced to an iteration of a newer, stronger hybrid.

In the Innovation and Improvement team at Iriss we encourage people to take on others' ideas. 'Take it! Steal with pride!', we say. What we mean is: make it your own and change something for the better. Of course it is important to acknowledge where an idea comes from, but doing so should not hold you back from using the idea. If you see a potential benefit in someone else's idea, go ahead and try it out.

"You put together two things that have not been put together before. And the world is changed. People may not notice it at the time, but that doesn't matter. The world is changed nonetheless."

- Julian Barnes

Seth Godin has taught us that 'ideas can't be stolen, because ideas don't get smaller when they are shared, they get bigger' (Godin, 2014). To maximise the possibility of discovering the ideas of others you need to be open to influence and:

- Learn from what has already been learned, used and implemented

- Learn from both successes and failures

- Look at other sectors / industries

- Look outside of work

- Look outside of your comfort zone

It can be difficult to share ideas within a competitive market where the protection of intellectual property is high on the agenda, but it is possible to keep an openness within parameters that call for less competitive measures. Can you be more open with colleagues internally or with partner organisations? Or would you be happy to mentor people from outside your sector who can learn from your approach? All sharing is good sharing, and everyone reaps benefits of both giving and receiving.

"If you have an apple and I have an apple and we exchange these apples then you and I will still each have one apple. But if you have an idea and I have an idea and we exchange these ideas, then each of us will have two ideas."

- George Bernard Shaw

Environment

Where can you be exposed to lots of new ideas to build on? Steven Johnson argues that the best environment for new ideas is created when people interact. Situations where you can learn from others, and share both successes and failures, will bring about the most inspiration. In turn, this will maximise your own arsenal of ideas and lead to innovation.

Expose yourself to people who have different interests, or work in a different field. With them come different understandings of how the world is arranged and how it operates. The more connected you are, the more likely it is that you will pick up ideas that you can make into something which has never existed before.

Don't forget about your own unique understanding of things, and share what you know as liberally as you take up the ideas of others.

Evidence suggests that creating distance between you and a problem you are trying to solve will help you be a better creative thinker (Jia and colleagues, 2009). The physical distance helps remove the psychological inhibitors that being close to a problem can create. Taking yourself away from the details of the problem opens up your thinking and lets you consider the issue from 'outside of the box'. If you cannot remove yourself from the problem, anything you can do to put yourself in a different mental space will also help you create distance, and therefore, a more creative approach to the problem.

The right combination

On the pages that follow are four examples of how ideas have been combined to create something new and innovative from something that already existed.

These examples illustrate different approaches to innovation that suit the context and environment of the respective ideas:

Turning parameters on their heads - reconceptualising established ideas Innovation from a position of need - meeting demand with free resources Putting context first - making use of locally available resources

Knowledge and collaboration - combining expertise to create a new approach

Ziferblat

Free coffee + free cake + responsibility + pay per minute = cafe

The Ziferblat in London is the first cafe in Great Britain to redistribute the monetary values of the elements that make a cafe. Where an ordinary cafe would charge for food and drink, Ziferblat charges for the time you spend on the premises. It costs 3p per minute to be in the cafe, during which time you have joint responsibility for the space, its use and upkeep. Everything else is free. The cafe actively encourages people to use the space to work, create and socialise. It wants to be defined by the people who use it, not by its bricks and mortar.

Clearly Ziferblat's innovative approach is meant to question not only the makings of a public social space and the idea of community, but to continuously question the value of what we choose to give and take, and the impact that this has on our environment. If time is literally money, but nothing else requires payment, what do you attribute value to and how do you nurture it?

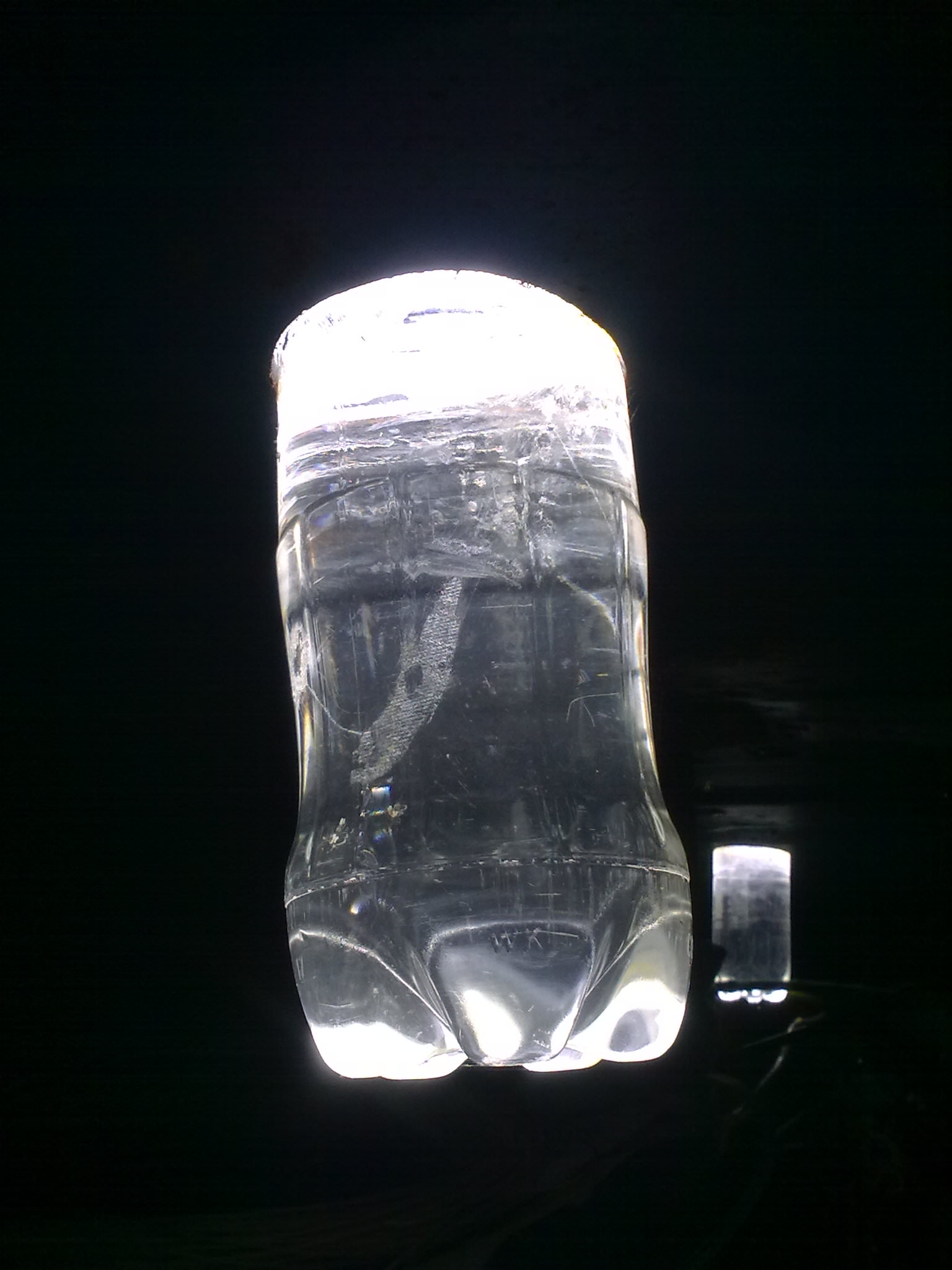

A litre of light

One clear PET bottle + purified water + bleach = free internal light source during daytime

In 2002, Brazilian mechanic Alfred Moser invented a new light source from materials that are easy to come by and free or relatively cheap. Seeking a solution to the lack of light in his house during electricity blackouts, he was reminded of how water refracts light, and one thought led to the next. The Moser light is now installed in millions of homes throughout areas of the world where electricity is expensive and difficult to come by.

What Moser created from very limited resources is, first and foremost, a solar light bulb which, during daytime, produced light with the same intensity as a 55W electric light bulb. But he also created a revolutionary eco-friendly, sustainable and low cost utility alternative, something that millions of people around the world can make use of. Because the materials are easy to source, and the product is easy to replicate, Moser's idea can be simply implemented by copying, and, given time, will no doubt be improved upon.

The NeoNurture baby incubator

The NeoNurture baby incubator is an example of the coming together of great ideas to create an even greater product that could change the world. It is also an example of how innovation can fail.

A group of MIT product designers collaborated to address the issue of infant mortality in the developing world. They researched and designed an incubator so simple that any part developing a fault could be replaced by a layperson, using standard Toyota car parts which are easy to come by the world over.

The product was celebrated in the media and named one of 'The 50 Best Inventions of the Year' by Time Magazine in 2010. However, it never went into production. The designers had focused their idea solely on meeting a specific need, overlooking the wider context and failed to acknowledge that manufacturing and donation channels influence what is used in the developing world. The team learned a valuable lesson: that it is not enough to want to change the world, you have to 'design outcomes' (Prestero, 2012).

Design that matters - neonurture

Dementia Dog

Dementia specialists + art students + dog trainers = Dementia Dog

The dementia dog project started at Glasgow School of Art where service design students came up with the idea of using trained assistance dogs to help care for people with dementia. Coming together with professionals who have the required specialist knowledge, Alzheimer Scotland, Dogs for the Disabled and Guide Dogs UK, the students' idea was refined and actualised.

This unique combination of ideas is winning hearts and minds on a large scale. It is a perfect example of how taking the very best ideas and repurposing them can make a world of difference for people who access support. The project, currently in its pilot phase, is exploring and testing three types of interventions:

Assistance

the dog helps with routine activities, provides reminders and is a companion

Intervention

the dog works with the person's support team to help reintroduce or maintain routine tasks

Facility

the dog works within a care home setting to enhance emotional and physical well-being

This is innovation at its best, and it is happening in Scotland.

Time

"Good ideas fade into view over a long piece of time."

- Steven Johnson

When you innovate there are always connections to be made and ideas to explore, and it may take considerable time to get to the combination which is right for you.

It is most important to focus on being effective, rather than being original, and to test out whether your idea will work in reality, or whether it needs altering.

Bring heart and determination into your ideas work, and remember that it's OK to fail; it's not OK to not try.

Objects gain their value through the situations in which they are placed, in other words what defines the value of an object is not the material it is made from or the function it serves but is defined by its position in a context. It might be that an originally worthless object becomes invaluable due to its unique status or that a costly mass-produced article is considered worthless almost immediately after being purchased. But it might also be that by reconstructing the settings for an item you change its context and therefore its value, setting it back to zero.

-Michael Johansson

The Swedish artist Michael Johansson, whose work Tetris graces the cover of this On... is a collector of objects which he uses in his creative processes. The above quote illustrates how his innovative approach to creating art has the power to redefine both the value and purpose of an object. When you

transfer this approach to ideas it is clear that only your imagination can limit the possibilities. Enjoy!

References

- Fast Company staff (2008) Innovation: old often becomes new

- Jia L, Hirt E and Karpen S (2009) Lessons from a faraway land: The effect of spatial distance on creative cognition, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 1127-1131

- Johansson M (2010) Objects subjected, Oslo: Norsk Kulturrad

- Johnson S (2010) Where do ideas come from?

- Ottery C (2011) Lindau Nobel meeting the cross-pollination of ideas

- Prestero T (2012) Design for people: Not awards

- Roitblat B (2012) Commonplace genius - borrowing ideas from other industries to solve business challenges

- Ferguson K (2012) Everything is a remix

- Videl F (2013) Cross-fertilisation drives innovation

- Barnes J (2013) Levels of Life, London: Jonathan Cape

- Mulgan G (2014) Design in public and social innovation, what works and what could work better (PDF), London: Nesta

- Godin S (2014) Why I want you to steal my ideas

- Turner M (2014) Our blender brain: How mixing ideas made us human

Written by Rikke Iversholt (Iriss) Reviewed by Dr Joyce Cavaye (Open University), Kathie Coonagh (North Lanarkshire Council) and Clare Bannister-Phillips (Dumfries and Galloway Council)

Layout and design support by Paul Hart.

Image credits

- Tetris by Michael Johansson © 2013 Images appear with permission by the artist.

- Innovation through exploration by @Leenders on Flickr

- Combination lock by @PaulV8 on Flickr

- Ziferblat by @Gilda on Flickr

- Litre of light by @Joimson on Flickr