Key points

- Hoarding Disorder (HD) exemplifies a ‘wicked problem’ as a complex condition, rooted in psychological, social, and biological causes, that has no single or simple solution.

- Lack of national guidelines or corresponding care pathway for HD in Scotland or the UK leads to implementation of reactive and harmful low-value care (LVC) interventions.

- Multidisciplinary practitioners need to work ‘as one’ and move beyond traditional roles and disciplines to de-implement ineffective and coercive measures and create a new unified transdisciplinary framework.

- Specialist skills and knowledge are required for practitioners involved in managing hoarding situations to enhance their confidence and understanding of the multifaceted nature of HD.

- Commissioners need to think differently and consider the substantial evidence base when commissioning services for HD and mental health.

- This Insight explores how transdisciplinary collaboration across health, social work, social care, housing, environmental health, emergency services, third sector support and other related professionals can transform practice and reduce low-value interventions for people with hoarding disorder.

Introduction

Drawing on a comprehensive review of literature on HD, this Insight examines care for people with lived expertise of hoarding, evidence-based practice and interventions, and explores some of the challenges faced by frontline practitioners involved in hoarding-related situations. HD is a complex mental health condition that stems from a combination of genetic, neurobiological, cognitive, and environmental factors. This complexity makes it difficult to treat with conventional methods and requires multi-agency involvement. However, evidence-based practice and practice-based evidence highlight the need to progress beyond multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary models towards a unified transdisciplinary approach (see p.19) to create an integrated framework ensuring more effective and sustainable hoarding interventions – comprising person-centred, harm reduction, and trauma-informed principles. Transdisciplinarity fosters a high level of collaboration between all stakeholders (e.g. people with lived expertise, clinicians, housing professionals, social workers, hoarding specialist practitioners, third sector support providers, environmental health, fire and safety) and calls for a common conceptual framework and methodology that is based on scientific evidence, shared objectives, terminology, best practice resources, and provision of adequate training and supervision.

The Insight begins with a definition of HD and how the condition overlaps with, or is distinct from, chronic disorganisation and self-neglect. Thereafter, the authors consider theoretical frameworks for HD and evidence-based interventions before looking at the complex policy landscape and areas relevant to HD – specifically health and social care (H&SC) and housing. Finally, implications for practice are discussed, which are then followed by recommendations for improvement in the provision of care and support as well as the ethical commissioning of services.

About hoarding

Hoarding Disorder

Hoarding disorder (HD) is classified as a mental disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 5th Edition (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) (World Health Organisation, 2022), which came into effect in the UK on 1st January 2022. Once seen as a subtype of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), HD is now recognised as a distinct condition (Tolin and colleagues, 2025).

HD is characterised by excessive acquisition and difficulty discarding due to a perceived need to save items regardless of use or value. Clutter is a defining feature of HD, and to be considered clinically significant, evidence must be present of distress and impairment caused by living spaces so severely cluttered that they cannot be used for important daily living functions such as sleeping, food preparation and washing or bathing (Frost and Hartl, 1996). This is an important distinction, since, if the volume of clutter does not impair a person’s daily living activities it is not considered problematic and any intervention should be focused specifically on implementing preventative measures. For example, change strategies that focus on substantiated hoarding behaviours (excessive acquisition and difficulty discarding) using evidence-based behaviour change methods and techniques.

HD affects personal and social relationships, education, and employment, (Kim and colleagues, 2021; Tolin and colleagues, 2008) and can pose serious safety risks, including falls, food contamination, infestations, and fires (Steketee and Frost, 2014). Cognitive functions that result in specific behaviours associated with problematic clutter are acquiring and saving, decision-making, memory and perfectionism (Frost and Hartl, 1996; Frost and colleagues, 1990). The disorder's effects are far-reaching – beyond the individual – impacting loved ones and wider communities.

It is difficult to ascertain exactly how many people are affected by HD, but a comprehensive systematic review reported a global prevalence of around 2.5% (Postlethwaite and colleagues, 2019). However, poor insight, self-criticism, (Gibson and colleagues, 2010) stigma (both societal and among professionals) and high levels of shame (Chou, 2018) associated with HD may discourage people from participating in research (and hinder help-seeking) (Huang and colleagues, 1998), leading researchers to conclude that 2.5% is a conservative base estimate and likely understates the true scope of the problem. The prevalence of provisional HD (the number of people who would potentially meet the diagnostic criteria) does not differ between males and females and increases linearly by 20% with every five years of age – primarily driven by difficulties with discarding leading to symptom severity (extreme clutter, distress and impairment) that results in populations over 55 experiencing higher rates of clinically significant HD at over 6% (Cath and colleagues, 2017). Retrospective studies of adults with lived expertise of HD report that most participants’ symptomatic behaviours started to emerge in early adolescence before the age of 20, usually around 11 to 15 years of age (Tolin and colleagues, 2010).

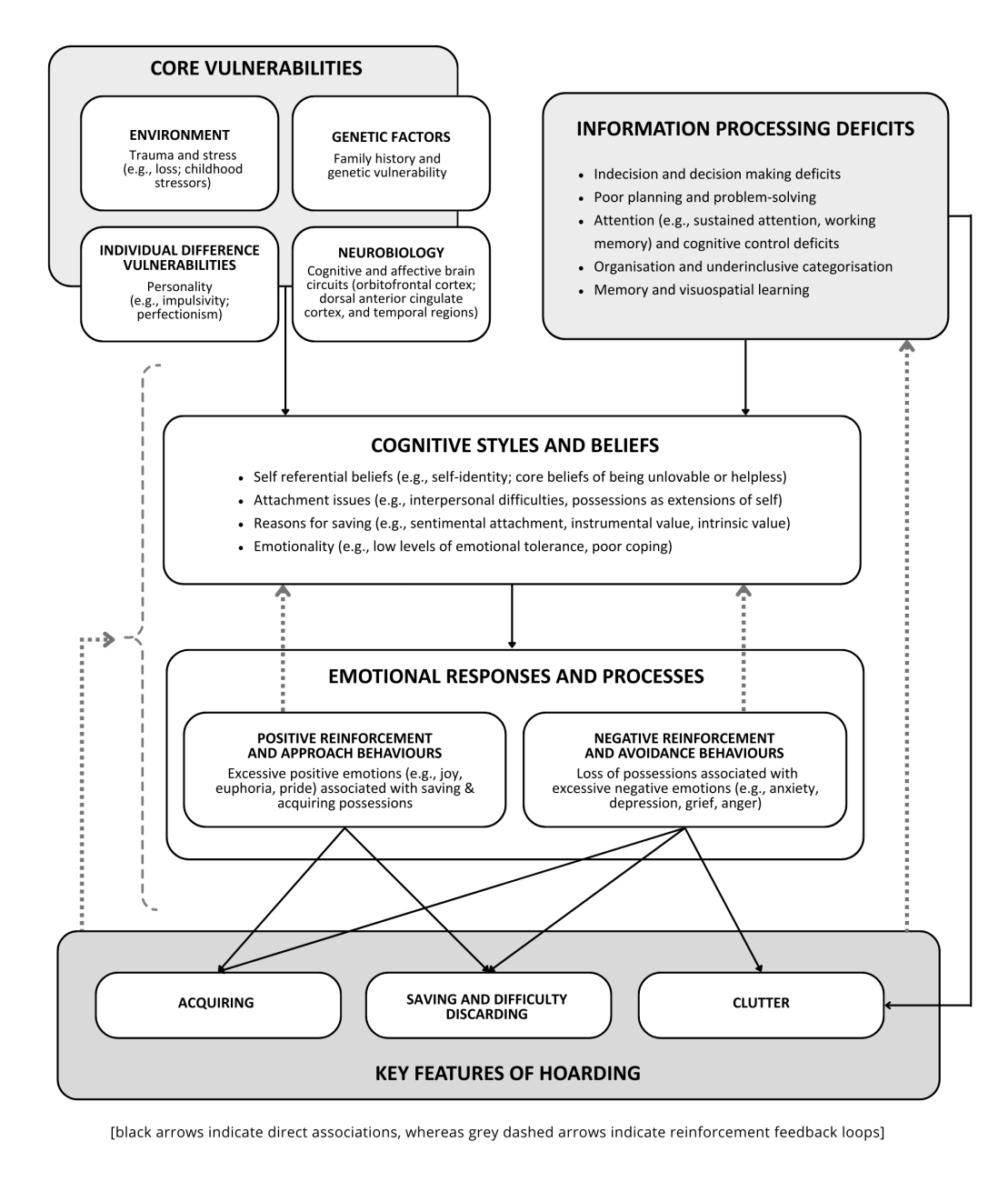

The aetiological model of HD (Timpano and colleagues, 2016) (fig.1) – outlining the causes or contributory factors to HD – shows the interplay of thoughts, emotions, and behaviours in its development and continuation. It provides a framework for understanding this multifaceted condition and the development of effective health and care strategies. Hoarding behaviours are rarely reducible to a single cause and, as shown in the model, they involve overlapping psychological, neurological, and environmental factors, including vulnerabilities such as traumatic life events (Sanchez, 2023). Saving is a key feature of HD, but there are other reasons for cluttered living spaces – HD being only one of them. For example, a person experiencing severe depression could have a cluttered home because they lack the energy and motivation to clean, but this is not the same thing as being unwilling to let go of possessions (Tolin and colleagues, 2025). HD is a highly comorbid condition, with up to 92% of those with lived expertise having received at least one other mental health diagnosis (Archer and colleagues, 2019; Harrison and colleagues, 2021). Some of the most frequent co-existing conditions include major depressive disorder (MDD), generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), and social phobia (Frost and colleagues, 2011). Common co-occurrence with neurodivergent conditions like autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) demonstrates that HD often manifests as part of broader neuropsychological vulnerabilities rather than as a discrete condition (Worden and Tolin, 2022).

Psychopathological and neurological conditions

Clutter alone is not diagnostic for HD. Multiple psychopathological or neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD and ADHD, traumatic brain injury (TBI) and hydrocephalus can result in extreme clutter and chronic disorganisation (CD). CD is ‘a quality – of-life issue, not a medical condition’ (Kolberg, 2007) and ‘is the result of the bad fit between people who organise unconventionally and the very conventional organising methods which exist for them to use’ (Kolberg, 2008). Evidence indicates, in these groups, clutter accumulation may arise from distinct cognitive and emotional mechanisms rather than the fears or beliefs typically seen in HD (Stuart and colleagues, 2021). Research relating to hoarding and neurodivergence, particularly in older adults, is limited, but a study by Goldfarb (2021) found that autistic adults aged 18–55 with hoarding behaviours were motivated by a need for emotional aids, and that they collected items related to special interests and had difficulties discarding. Other research found that approximately 34% of children aged 7–13 with ASD were reported to have moderate to severe levels of hoarding behaviours (La Buissonnière-Ariza, 2018). In autism, rigidity of thinking and perfectionism can similarly result in decision paralysis and discomfort with change (Halstead and colleagues, 2018). Emotional and sensory factors also contribute. For autistic individuals, possessions often hold strong sensory or associative value, providing predictability and comfort in the face of uncertainty (Halstead and colleagues, 2018). Individuals with ADHD may struggle with inattention and task avoidance, leading to loss of control over accumulation, and may experience comparable attachment to objects that symbolise potential or unfinished intentions, reinforcing saving behaviours (Stuart and colleagues, 2021).

While hoarding behaviours in ADHD and ASD may resemble HD phenomenologically, they stem primarily from executive dysfunction, cognitive rigidity, and emotional regulation differences rather than obsessive compulsive mechanisms per se (Halstead and colleagues, 2018; Stuart and colleagues, 2021). Intolerance of uncertainty and avoidance of distress can further perpetuate clutter, as can sensory sensitivities that make the physical process of sorting or cleaning overwhelming. Meaning that whilst symptoms present similarly (ie clutter) the causes differ and therefore require tailored person-centred interventions to ensure effectiveness.

Self-neglect

Also known as ‘domestic squalor’ or ‘Diogenes syndrome’, self-neglect and hoarding often get conflated, and although they can be related – especially syllogomania (the hoarding of rubbish) they do not always co-exist and are two separate conditions. There is no universally adopted definition for self-neglect, but it is commonly described as someone who demonstrates a lack of care for themselves and their living environment, and who is less likely to accept help or assistance from health, care or community services. An early clinical study of neglect in older adults found that many had conducted successful careers and had a good family upbringing. The study also suggested that self-neglect may be a reaction late in life to stress in a person with certain types of characteristics, such as aloofness, reality distortion and rapid and exaggerated mood changes (Clark and colleagues, 1975). A report by Braye, Orr and Preston-Shoot (Braye and colleagues, 2011) found no conclusive evidence on causation, or on the effectiveness of particular interventions but highlighted that, as with HD, clearing interventions alone are ineffective and assistance with daily living is likely to be more effective, particularly where self-neglect is linked to poor physical functioning. The report also acknowledged tensions between respect for autonomy and a perceived duty to preserve health and wellbeing and stated that building good relationships is vital to establishing and maintaining interventions to enable decision-making capacity to be monitored.

Theoretical frameworks

Several theoretical models and frameworks have been proposed to support understanding of HD and to inform intervention design. Frost and colleagues (1996) developed the foundational cognitive-behavioural model, highlighting five key features: difficulty discarding, excessive acquiring, problems with organisation and decision-making, emotional attachment to possessions, and avoidance of distressing behaviours like discarding. This seminal paper remains important today because it established a coherent, empirically grounded framework that still underpins how HD is conceptualised, assessed, and translated into intervention design across clinical and applied settings.

Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT)

It is perhaps unsurprising therefore that cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is the most studied and most empirically supported treatment for HD. CBT is a talking therapy that helps an individual to identify negative or unhelpful thinking with the aim of changing thoughts and behaviours. Previous studies report substantial post-symptom reduction after individual CBT (Tolin and colleagues, 2015; Bodryzlova and colleagues, 2019; Rodgers and colleagues, 2021). However, a new comprehensive meta-analysis by O’Brien and Law (2025) of 41 studies for psychological interventions for HD in randomised and non-randomised trials extending beyond CBT provides a more nuanced picture. This first of its kind, analysis found that ‘there are no discernible distinctions between CBT and alternative psychological interventions’ and that ‘despite most trials documenting positive outcomes, few achieve an average clinically significant improvement in HD symptoms, emphasising the need for more effective interventions or a multifaceted approach’ (p749) with improved study design and greater participant diversity in HD research. O’Brien and Law (2025) also report dropout rates at around 20%, emphasising the importance of addressing motivational challenges in HD treatment. When a person with HD lacks motivation and avoids dealing with risks and issues, adopting a harm reduction attitude is the best approach. Poor insight often results in a lack of awareness about the implications of their accumulated possessions and rejecting offers of help (Bratiotis and colleagues, 2021). Meta-analyses show that motivational interviewing is equivalent to or better than other treatments such as CBT (Hall, 2012), which is important to recognise since we know that ‘people start to work on their hoarding problem when the reasons for change outweigh the reasons for not changing, and not a minute sooner’ (Tolin, and colleagues, 2014, p36).

Like most cognitive-behavioural treatments, better outcomes tend to be positively correlated with higher motivation and readiness for change (Crane and colleagues, 2024). Tolin and colleagues (2025) highlight that ‘determining readiness and ability for CBT is critical’ (p670), and presumes that the [person] desires assistance, as it is unethical to force intervention if the [person] is cognitively competent, does not want treatment, and there are no acute risks to self or others. Tolin and colleagues (2025) also stated that the cross-cultural efficacy of CBT for HD is unclear, as are the effects of cultural modifications to the treatment.

Tolin and colleagues (2025) clinical trial results demonstrate that (CBT) treatment gains are particularly modest amongst older than younger adults. However, there is a dearth of research on cultural adaptations to both HD treatment and CBT and how current interventions can be tailored to diverse populations. Most studies conducted are in Western nations with a majority (90%) of White participants – leading a recent review paper, ‘Considering Culturally Responsive CBT for Ethnically Diverse Populations’, to conclude that meeting the needs of all will require the same time, effort and funding to studying culturally competent CBT as that which has been afforded to studying CBT (Huey and colleagues, 2023).

As O’Brien and Law (2025) conclude: ‘Given that therapy linked differences do not appear to impact efficacy, patient preference emerges as a critical consideration, indicating scope for more personalised treatment plans that align with individual preferences… whether in group or individual format, with or without home visits, delivered face-to-face or virtually and so on.’ (p749).

Attachment-based models

Mathes and colleagues (2020) proposed an attachment-based model, suggesting that unmet emotional needs, such as fear of abandonment or mistrust of others, lead people to form emotional bonds with objects.

Object-affect fusion (OAF) (Kellett, 2004) refers to the central psychological process that helps to explain our thoughts, feelings and behaviours, and when applied to HD, individuals with lived experience seem to meld the emotions they associate with objects to the objects themselves. These concocted emotions take root and make decisions about discarding difficult.

For example, an individual who has experienced repeated interpersonal loss or unreliable caregiving may develop a fear of abandonment and mistrust of others. In response, they may begin to form strong emotional bonds with possessions that feel stable, predictable, and non-judgemental. A seemingly low-value object, such as a broken chair or a stack of old newspapers, may become imbued with feelings of safety, continuity, or identity. Through object-affect fusion, the emotions associated with comfort or security are no longer simply evoked by the object but are experienced as intrinsic properties of the object itself. Consequently, discarding the item is perceived not as a neutral act of disposal but as a distressing loss, akin to severing an attachment relationship, triggering intense anxiety, grief, or a sense of threat.

Trauma-informed therapy

People with HD often report more early life stress and traumatic events, such as loss or abandonment, than those without HD, and greater trauma is linked to increased severity (Sanchez, 2023). Evidence-based trauma-informed therapy focuses on a compassionate, person-centred approach that involves exploring and processing the emotional triggers that lead to hoarding behaviour, developing coping mechanisms, and helping individuals regain a sense of control while promoting their overall well-being. Highlights from a review of international evidence on enablers and barriers to trauma-informed approaches found that for people with lived experience of psychological trauma, trauma-informed approaches can improve wellbeing, reduce emotional difficulties and have a positive impact on families and relationships. An expected outcome of the trauma-informed approaches outlined in Scotland’s National Trauma Transformation Programme (see Principles and approaches in policy, p.[11]) is that people with experience of trauma will have improved access to specialist treatment or services where required and increased completion rates of treatment (Scottish Government, 2023).

Interventions

Psychology led model

Due to the complex nature and multifaceted problems associated with HD, it is recognised as a difficult condition to treat and requires long-term, consistent support from practitioners who have an appropriate level of skills, knowledge and expertise. Haighton and colleagues (2023) at Northumbria University recommend a psychology led model that would allow for diagnosis of HD as well as coordinated care based on each [person]’s mental stability to cope with intervention. However, a psychology-led model could make some people with lived experience of HD feel stigmatised, which can lead to a decrease in help-seeking behaviour and intention to use psychological services (Vogel and Wade, 2009). Stigma around mental illness is especially an issue in some diverse racial and ethnic communities and can act as a barrier to people from those cultures accessing mental health services (Adade and colleagues, 2025).

Clearouts

Clearouts are the removal of a large amount of ‘clutter’ (belongings) from a client’s home – usually in a matter of days, and the client is unlikely to be involved in every decision made about which items are kept or discarded. Clearouts as an intervention for HD can without doubt be identified as low value in accordance with the typology of LVC developed by Verkerk and colleagues (Verkerk and colleagues, 2018) that comprises three categorised reasons for care being low value: ineffective care, inefficient care and unwanted care. It is unlikely to be of benefit to an individual given the harm, costs, available alternatives, or preferences of the individual (Patey and Soong, 2023). Despite the growing evidence base on the harmful effects of clearouts, they are still used prolifically as a solution to hoarding (Kysow and colleagues, 2024).

Research into evidence and best practice in primary care reaffirmed that clearouts cause significant distress and anxiety – exacerbating mental ill health (Haighton and colleagues, 2023; Morein-Zamir and Ahluwalia, 2023), and without any behavioural therapy, almost 100% of people who experience a clearout will regress to hoarding behaviours more rapidly (Bratiotis and colleagues, 2011). Coerced or enforced clearouts raise ethical dilemmas and create tension between autonomy and protection. For example, clearance of a person’s belongings may reduce environmental risks but can be traumatising, lead to recidivism, and damage trust (Noyes and colleagues, 2024). Unsolicited interventions involving decluttering can be a traumatic experience, creating distress over parting with possessions and intensifying the severity of HD (Hanson and Porter 2021).

Relatedly, the overarching principle underlying Part 1 of the Adult Support and Protection (Scotland) Act 2007 states that any intervention in an individual’s affairs should provide benefit to the individual and should be the least restrictive option of those that are available, which will meet the purpose of the intervention (Scottish Government, 2022). Currently, however, unregulated clearouts remain a persistent practice, especially within social housing and local authority-led interventions. Despite policy shifts towards person-centred approaches, studies from large housing providers show that clearouts often proceed based on fire and safety concerns – sometimes unwarranted if risks in the home are neither imminent nor in serious breach of tenancy agreements – with minimal regard for the individual's autonomy or underlying mental health needs (Porter and Hanson, 2022).

Research seeking to understand the reasons for HD clearouts (Kysow, 2024) found that the people commissioning them frequently used modified terms such as ‘therapeutic clearouts’ and ‘trauma-informed cleans’, or when talking to people with lived experience of HD, used euphemisms like ‘downsizing’ or ‘decluttering’ – believing more ambiguous language was less upsetting for people. Although clearouts are driven by a desire to mitigate risks in the home, the lack of regulation, clinical oversight, and practice guidelines means people with HD are subject to invasive, non-consensual interventions that fundamentally breach ethical standards, undermine autonomy and trust, and are harmful – sometimes fatal when consideration is given to the level of suicidal ideation that is reported amongst people who have been threatened with or have experienced an enforced clearout (Fay, 2024, p36; Koenig and colleagues, 2013; Large and colleagues, 2014; Ward-Ciesielski and Rizvi, 2021).

Components for successful intervention

Recommended interventions for HD span a range of psychological, medical, and community-based approaches designed to address both the symptoms and underlying causes – for example, talking therapy and peer-led support groups. Trust and compassion are essential, as is a consistent and long-term relationship (Morein-Zamir and Ahluwalia, 2023). HD is a difficult condition to treat and even among other severe mental disorders HD is unique in requiring multidisciplinary skills and expertise to address both the behaviours and the symptoms. The DESIRE method (Fay, 2024) incorporates research, evidence-based models (ie transtheoretical model of behaviour change (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1982), strategies and therapeutic techniques (ie harm reduction (Tompkins, 2015), and motivational interviewing (Miller and Rollnick, 2013), with skills, knowledge and experience to help practitioners assess and manage hoarding situations with compassion and without judgement.

Home assessment tools

The Clutter Image Rating Scale (CIRS) (Steketee and Frost, 2014) is the most widely used tool for HD – perhaps due to (a) its simplicity of use, (b) empirical use, and/or (c) lack of alternative options, but it is vital to recognise that volume of clutter is only one factor to be considered when assessing hoarding-related risks and issues. The CIRS can be a blunt instrument as it focuses solely on the volume of stuff in a home, but it tells us nothing about the person(s) living in the home and can be interpreted differently by users based on their personal standards or risk threshold. Currently, most existing hoarding protocols reference the CIRS and make intervention decisions based on the ratings identified. However, we strongly advise against making policy or practice decisions based solely on the CIRS and encourage using it along with another assessment tool such as HEATH© (see below) or others that can be accessed via Hoarding Academy.

Home environment assessment tool for hoarding (HEATH©) (Woody and Bratiotis, 2024) was created to assess only the most important health and safety risks in the home, to help people who have severe clutter to be safer in their home. The HEATH covers five domains of risks (safe pathways, fire safety, structural integrity, health and wellness, and sanitation) that can occur with a high volume of clutter in a home. Each domain includes assessment areas that were carefully selected and rigorously field tested by multidisciplinary stakeholders for their importance in home safety. Risk assessment in hoarded homes is not easy. Different disciplines often have different priorities, as well as different understandings of what risk means. The Centre for Collaborative Research on Hoarding at the University of British Columbia (UBC) collaborated with community partners including fire and safety services, social workers and housing providers to create this universal tool designed for professionals in any discipline or area of community practice working with hoarding. It enables service providers from diverse disciplines to communicate more effectively, and plan hoarding interventions based on shared goals and priorities.

HATCH is the UK's first child-specific hoarding risk assessment tool, developed by Amy Coulson, Holistic Hoarding (2025). This pioneering resource puts children at the heart of safeguarding and is freely accessible to all practitioners who support children and families in hoarded homes.

A complex policy landscape

Pathways to support

Currently, there is no established care pathway for HD in Scotland or across the UK. There are no Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidelines and the existing National Institute for Care and Health Excellence (NICE) guidelines classify HD under obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), which is somewhat outdated and there appears to be no appetite to bring them up to date anytime soon. That said, in 2025, during a BBC interview with Paulette Hamilton, MP, Heather Matuozzo (Clouds End CIC) urged the MP to request a discussion in the Houses of Parliament about the pressing need for national guidelines on HD. This was followed up with an open letter sent from the UK Hoarding Partnership to Members of Parliament reinforcing the need for strategic guidelines, integration of services, increased resources and improved data collection. In October 2025, almost 30 years after the seminal research paper on HD was published (Frost and Hartl, 1996), history was made when HD and mental health was discussed for the first time on the Floor in the House of Commons. As a result, a meeting will be held in January 2026 at Portcullis House in Westminster to discuss the matter further.

Although the NHS recognise HD as a mental health condition (NHS inform only reference HD in relation to OCD), receiving a clinical diagnosis is exceedingly rare, and without a care pathway people with HD are being excluded from much-needed psychological support in a time where demand for mental health services far outstrips supply. This situation places additional responsibility on local authorities and housing providers who often intervene at crisis points when there is a health or safety concern. Furthermore, many frontline professionals lack specialised training to address HD as a mental health issue (Kaminskiy and colleagues, 2025). Since no discipline is singularly mandated or equipped to take responsibility for managing hoarding-related situations, what ensues is duplication of effort, variable responses to risk, neglect of safeguarding responsibilities and the implementation of LVC interventions – such as enforced clearouts. However, it is worth stating that low-value does not mean low-cost. The UK average cost of clearing a hoarded home is between £3,500 and £4,000 with more extreme cases being as high as £25,000 (Clean Team Scotland, 2024).

In Scotland, HD is most often referred for intervention under Adult Support and Protection (ASP) when there is a safeguarding concern, and/or where HD is categorised as a form of self-neglect. The Adult Support and Protection (Scotland) Act 2007 places a duty on councils to make inquiries to assess if a person meets the three-point criteria of the Act, that they are:

- Unable to safeguard their own well-being, property, rights or other interests

- At risk of harm

- Affected by disability, mental disorder, illness or physical or mental infirmity

The Act does not absolve local authorities of responsibility for adults at risk who do not meet its three-point criteria. Councils have responsibility to consider other interventions under other legislation, including the general welfare provisions in Section 12 of the Social Work (Scotland Act 1968, or where a person’s mental capacity is in question, under the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003, or Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000.

The Self-directed Support (Scotland) Act 2013 also makes legislative provision where there are assessed care needs, providing other routes to support. Yet, it is reported anecdotally, that self-directed support (SDS) is under-utilised for the purposes of HD help and support interventions. While SDS Option 1 (Direct Payments) can provide the flexibility that is often needed, they are not for everyone since they come with the responsibility of managing funds and potentially becoming an employer. Furthermore, shrinking budgets have led to a reduction in, or removal of support packages in a challenging financial climate. Audit Scotland’s ‘Local government in Scotland’ (2018) report identifies growing pressures on budgets for social care, including SDS, if current trends continue. Plus an ALLIANCE (2025) briefing, whilst recognising the limited scale of their survey, identifies significant proportions of SDS care packages being reassessed, reviewed and cut. Research commissioned by Social Work Scotland on people's experiences of SDS, is expected to confirm these trends and provide additional insights (forthcoming – early 2026).

Public sector funding to Scotland’s voluntary sector dropped in real terms by around £177 million between 2021 and 2023 – a 5 % reduction – meaning third sector organisations delivering critical support services are being asked to do more with less resource and face increased financial insecurity (SCVO, 2025). The voluntary sector sometimes provides support to people with HD in a range of ways – as community connectors, in providing peer support, or via specialist teams that offer holistic support e.g. helping people de-clutter or addressing tensions with landlords or tackling debt as the result of accrual. It is recognised, however, that in many localities these services either do not exist or there is variability between areas with third sector organisations also facing funding uncertainty.

Principles and approaches in policy

Across the policy landscape in H&SC, both person-centred and trauma-informed care is advocated. Person-centred care should be considerate of what matters to an individual, providing personalised and co-ordinated support around them, that also enables people to make choices, manage their own health and live independent lives, where possible, and where professionals work in partnership with individuals and their families.

Scotland has also invested in a National Trauma Transformation Programme to create a workforce capable of recognising where people are affected by trauma and adversity, and able to respond in ways that prevent further harm, support recovery, help address inequalities and improve life chances. The Scottish Government (2021) trauma informed model is underpinned by five principles: safety, trustworthiness, choice, collaboration, and empowerment. It recognises the importance of relationships and seeks to prevent re-traumatisation. Research shows that traumatic life events can make people more susceptible to HD and reported that 55% of a sample of adults with hoarding behaviours had experienced trauma before the onset of their symptoms (Grisham, 2006).

There is also the new Scottish Government (2025) Health and social care service renewal framework (SRF) that includes the Prevention principle (focused on prevention and proactive early intervention; reducing inequalities and stigma), and the People principle (focused on being responsive and respecting individual needs; delivering outcomes that matter to people and are person-centred; shared decision-making where services are equitable and trust (the person’s) choices. Early intervention will avoid crisis responses such as enforced clearouts and will enable more humane, practical help and therapeutic support interventions to be put into place. The Prevention principle was reinforced by Dr Zubir Ahmed, MP for Glasgow South West and Parliamentary Under-Secretary (Department of H&SC) during the aforementioned House of Commons discussion when they said, ‘Through our 10-year health plan, we have set long-term reforms to make mental health a core priority of the NHS and to move from crisis care to prevention and early intervention.’ Research on early intervention and children with HD is scarce. However, a review of what we know about hoarding behaviours among care-experienced children stated there is ‘growing anecdotal evidence to suggest that care-experienced people are more likely to develop hoarding behaviours in childhood in comparison to peers, which may continue into and be exacerbated in adulthood’ (Close and colleagues, 2024).

Child Protection and Adult Support and Protection also form part of a wider Public Protection approach currently being fostered in Scotland. The formation of a National Public Protection Leadership Group in June 2024 encourages multi-agency and whole systems approaches that promote greater interconnectivity, prevention and early intervention, along with greater coherence and simplification of public protection policy . It aims to provide a supportive environment to share best practice and develop national initiatives.

Scotland's housing and tenancy sustainment policies in line with the Housing (Scotland) Act 2001 are implemented at a local level by housing providers and local authorities, and often advocate collaboration with other agencies, such as H&SC. Tenancy agreements typically state that properties must be kept in a ‘reasonable state of cleanliness’ and landlords can initiate legal action (such as eviction proceedings) if the condition of a property deteriorates. However, enforcement action is rarely pursued as most housing professionals agree that a holistic and person-centred approach involving working alongside tenants to provide the support needed leads to better results (Gardelli, 2022).

Adults who hoard may need support under Section 53 of the Adult Support and Protection Act (Scotland) 2007 and must meet the aforementioned three-point criteria for support that includes 'being affected by disability, mental disorder, illness or physical or mental infirmity.' Since HD often involves safety concerns and long-term mental impairment affecting normal activities, it could be classed as a disability. Section 6(1) of the Equality Act 2010 states that a person (P) has a disability if: (a) P has a physical or mental impairment, and (b) the impairment has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on P's ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities.

Social landlords and housing authorities therefore should be referring tenants in cases that feature HD to ASP where it is a safeguarding issue, and in cases where housing is provided by local authorities, there is a legal duty to refer and cooperate with ASP under Section 5 of the Act.

Discussion and implications for policy and practice

HD exemplifies a ‘wicked problem’ (Rittel and Webber, 1973): a multifaceted condition that resists simple solutions because its causes and consequences intersect biological, psychological, social, and environmental systems. As such, traditional service structures – divided by professional boundaries and statutory responsibilities – struggle to provide adequate and consistent responses. The lack of a national care pathway perpetuates fragmented, reactive, and often coercive practices, such as enforced clearouts that do more harm than good.

At present, most intervention occurs at crisis point when risk escalates to health or safety concerns and there is a statutory duty to intervene through ASP. The ethical dilemmas faced by frontline staff – balancing autonomy with safeguarding duties – are significant and contribute to moral distress and require good supervision, mentoring and managerial oversight.

Adopting trauma-informed and harm-reduction approaches can mitigate these tensions. Research repeatedly demonstrates that forced decluttering and clearouts are not only ineffective but can retraumatise individuals, erode trust, and increase the likelihood of recurrence (Haighton and colleagues, 2023; Noyes and colleagues, 2024). Instead, evidence indicates that sustainable change emerges through long-term, relationship-based support that emphasises collaboration, emotional safety, and gradual behavioural progress.

Transdisciplinary working

While multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches have made progress, they remain limited by siloed structures. A transdisciplinary model – where boundaries between disciplines are intentionally dissolved – offers the most promising route forward. This approach reframes HD not as an issue belonging to one sector but as a shared responsibility requiring an integrated conceptual framework, shared language, and coordinated interventions.

Transdisciplinarity is underpinned by three principles:

- Shared ownership: practitioners, commissioners, and people with lived experience co-produce goals and solutions.

- Unified methodology: assessment, terminology, and outcome measurement are standardised across sectors.

- Continuous learning: practice is informed by evidence, reflection, and supervision, with opportunities for specialist training.

When implemented well, transdisciplinary practice can reduce duplication, align safeguarding and tenancy sustainment goals, whilst fostering earlier, preventative support. A study (Gibb, 2009) relating to transdisciplinary working in the development of health and social care provision in mental health, reported ‘evident benefits for team members, management and service users’ (p339) and feedback from study participants, who formed a collaborative working group, identified the following positive outcomes of working together (p347):

- A sense of common purpose

- More efficient inter-agency communication pathways

- A more efficient and flexible service, increasing the responsiveness of the service to clients, allowing team members to manage ‘red tape’ more effectively

- An increase in staff morale resulting from a decrease in isolation

- A good level of team support through the availability and willingness of team members to share with and listen to each other

- Joint training opportunities

Recommendations for improvement

Building on the insights above, the following recommendations outline the system-level changes needed to embed ethical, effective, and sustainable responses:

- Develop national guidance and care pathways

A dedicated national framework for HD should be established, integrating mental health, housing, social work, social care and environmental health. This would provide consistency in assessment, intervention, and referral processes across Scotland. - Invest in specialist training and supervision

All frontline practitioners should receive training on HD as a mental health condition, incorporating trauma-informed practice and harm reduction principles. - Commission services differently

Commissioners should prioritise early intervention and prevention rather than crisis response, funding community-based, psychologically informed services capable of supporting long-term behavioural change. - Promote ethical and evidence-based practice

Clearouts and similar coercive interventions should be recognised as low-value care and replaced with relational, person-centred approaches supported by evidence-based resources such as HEATH© and the DESIRE method. - Embed lived experience in service design

Co-production with people who have lived expertise of HD should guide all policy, training, and commissioning decisions to ensure interventions are compassionate, relevant, and effective. - Foster transdisciplinary networks

Local authorities and health boards should establish formal transdisciplinary forums to share learning, align risk assessment protocols, and coordinate support pathways across agencies on hoarding, and feed into national forums to drive improvement for sustained commitment and focus.

Conclusion

Hoarding Disorder demands a paradigm shift in how services conceptualise and respond to complex needs. Without a unified national approach, people with lived experience of HD continue to face inconsistent, and at times harmful, interventions. Building a transdisciplinary framework rooted in compassion, evidence, and collaboration would enable practitioners to move from crisis management to prevention, and from coercion to care.

Commissioners, policymakers, and practitioners alike are called to think differently: to invest in training, coordination, and ethical service design that truly honours autonomy, promotes wellbeing, and upholds the rights and dignity of people affected by HD.

References

- Adade AE, Agyei DN, Nyarko E KS et al (2025) Does stigma influence intentions to seek mental health care? A study among adults attending University in Ghana. PLOS Mental Health, 2(8), e0000378.

- Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000

- Adult Support and Protection (Scotland) Act 2007

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed).

- Archer CA, Kyara M, Garza K et al (2019) Relationship between symptom severity, psychiatric comorbidity, social/occupational impairment, and suicidality in hoarding disorder. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 21, 158-164

- Bodryzlova , Audet JS, Bergeron K et al (2019) Group cognitive‐behavioural therapy for hoarding disorder: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. Health and Social Care in the Community, 27(3), 517-530

- Bratiotis C, Schmalisch C and Steketee G (2011) The hoarding handbook. Oxford University Press, Inc.

- Braye S, Orr DO and Preston-Shoot M (2011) Self-neglect and adult safeguarding.

- Cath DC, Nizar K, Boomsma D et al (2017) Age-specific prevalence of hoarding and obsessive compulsive disorder: a population-based study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(3), 245-255

- Chou C-Y, Tsoh J, Vigil O et al (2018) Contributions of self-criticism and shame to hoarding. Psychiatry Research, 242, 488-493

- Clark ANG, Mankikar GD and Gray I (1975) Diogenes syndrome: a clinical study of gross neglect In old age. The Lancet, 305(7903)

- Clean Team Scotland (2024) What is the average cost to clean a hoarder house

- Close H, Vincent S, Alderson H et al (2024) What do we know about hoarding behaviours among care-experienced children (CEC)? A systematic review. Cogent Psychology, 11(1).

- Crane C, Hotton M, Shelemy L et al (2024) The association between individual differences in motivational readiness at entry to treatment and treatment attendance and outcome in cognitive behaviour therapy: a systematic review. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 48(6), 1066-1089

- Equality Act 2010

- Fay L (2024) A pragmatic approach to chronic disorganisation and hoarding - using the DESIRE method. Jessica Kingsley Publishers

- Frost RO and Hartl TL (1996) A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(4), 341-350

- Frost RO, Marten P, Lahart C et al (1990) The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 449–468

- Frost RO, Steketee G and Tolin DF (2011) Comorbidity in hoarding disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 28(10), 876-884.

- Gardelli S (2022) Social housing tenants and hoarding behaviour: a landlords’ perspective (in collaboration with Housing Options Scotland, Issue)

- Gibb C, Morrow M, Clarke CL et al (2002) Transdisciplinary working: evaluating the development of health and social care provision in mental health. Journal of Mental Health, 11(3), 339–350.

- Gibson AK, Rasmussen J, Steketee G et al (2010) Ethical considerations in the treatment of compulsive hoarding. Cognitive and behavioural Practice, 426-438

- Goldfarb Y, Zafrani O, Hedley D et al (2021) Autistic adults’ subjective experiences of hoarding and self-injurious behaviors. Autism, 25(5), 1457–1468

- Grisham JR, Frost RO, Steketee G et al (2006) Age of onset of compulsive hoarding. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 20(5), 675-686

- Haighton C, Caiazza R and Neave N (2023) In an ideal world that would be a multiagency service because you need everybody’s expertise. Managing hoarding disorder: A qualitative investigation of existing procedures and practices. PLOS ONE, 18(3), e0282365.

- Hall K (2012) Motivational interviewing techniques: Facilitating behaviour change in the general practice setting. Australian Family Physician, 41(9), 660–667

- Halstead EJ, Dittner AJ, Ferrero M et al (2018) I find it difficult to discard things. Hoarding behaviours in adults with autism spectrum condition. Autism, 22(6), 733-744

- Harrison C, Fortin M, van den Akker M et al (2021) Comorbidity versus multimorbidity: Why it matters. Journal of Multimorbidity and Comorbidity, 11

- Housing (Scotland) Act 2001

- Huang C-Y, Liao H-Y and Chang S-H (1998) Social desirability and the clinical self-report inventory: Methodological reconsideration. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54(4), 517-528

- Huey SJ, Park A, Galán CA et al (2023) Culturally responsive cognitive behavioral therapy for ethnically diverse populations. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 19, 51–78.

- Kaminskiy E, Staras C, Brown S et al (2025) Falling between the cracks: investigating the competing challenges experienced by professionals working with people who hoard. PLOS One, 20(5), e0323389

- Kellett S and Knight K (2004) Does the concept of object-affect fusion refine cognitive-behavioural theories of hoarding? British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies, 31(4), 457-461

- Kim DD, Do LA, Daly AT et al (2021) An evidence review of low-value care recommendations: inconsistency and lack of economic evidence considered. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(11), 3448-3455

- Kolberg J (2007) Conquering Chronic Disorganization. Squall Press

- Kolberg J (2008) What every professional organizer needs to know about chronic disorganization. Squall Press

- Kysow K (2024) Understanding hoarding clean-outs: a public Scholar approach. The University of British Columbia. Vancouver

- Kysow K, Woody S and Bratiotis C (2024) Clean-outs as a strategy for community agencies to address hoarding. University of British Colombia

- La Buissonnière-Ariza V et al (2018) Presentation and correlates of hoarding behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorders and comorbid anxiety or obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 8(12), 4167-4178

- Large M, Ryan C, Walsh G et al (2014) Nosocomial suicide. Australasian Psychiatry, 22(2), 118–121.

- Mathes BM, Timpano KR, Raines AM et al (2020) Attachment theory and hoarding disorder: A review and theoretical integration. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 125, 103549

- Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003

- Mille WR and Rollnick S (2013) Motivational interviewing: helping people change (Third Edition). The Guildford Press

- Morein-Zamir S and Ahluwalia S (2023) Hoarding disorder: evidence and best practice in primary care. British Journal of General Practice, 73(729), 182-183

- Noyes S, Van Houten S and Wilkins E (2024) A ‘friendly visitor’ volunteer intervention for Hoarding Disorder: Participants’ perceptions. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 12(2), 1-10.

- O'Brien E and Laws KR (2025) Decluttering minds: psychological interventions for hoarding disorder-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 181, 738-751

- Porter B and Hanson S (2022) Council tenancies and hoarding behaviours: a study with a large social landlord in England. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(6), 2292-2299

- Postlethwaite A, Kellett S and Mataix-Cols D (2019) Prevalence of hoarding disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 256, 309-316

- Prochaska JQ and DiClemente CC (1982) Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 19(3), 161-173

- Rittel HWJ and Webber MM (1973) Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences (Vol. 4, pp. 155–169). Springer

- Rodgers N, McDonald S and Wootton BM (2021) Cognitive behavioral therapy for hoarding disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 290, 128-135

- Sanchez C, Linkovski O, van Roessel P et al (2023) Early life stress in adults with hoarding disorder: A mixed methods study. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 37, 100785

- SCDC (2025) Sector responds as Edinburgh community organisations face funding cuts. Scottish Community Development Centre

- Scottish Government (2023) Enablers and barriers to trauma-informed systems, organisations and workforces: evidence review

- Scottish Government (2025) Health and social care service renewal framework (SRF)

- SCVO (2025) Scottish voluntary sector dealt £177million real-terms funding cut. Scottish Council for Voluntary Organisations

- Self-directed Support (Scotland) Act 2013

- Social Work (Scotland) Act 1968

- Steketee G and Frost RO (2014) Treatment for hoarding disorder. Workbook. Oxford University Press

- Stuart AL, Le Drew K and Mataix-Cols D (2021) Hoarding in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: clinical correlates and impact on everyday functioning. Journal of Attention Disorders, 25(12), 1643–1654

- Timpano KR, Muroff J and Steketee G (2016) A review of the diagnosis and management of hoarding disorder. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 3, 394–410

- Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G et al (2008) The economic and social burden of compulsive hoarding. Psychiatry Research, 160(2), 200-211

- Tolin DF, Frost RO and Steketee G (2014) Buried in treasures: help for compulsive acquiring, saving, and hoarding (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press, Chicago

- Tolin DF, Worden BL and Levy HC (2025) State of the science: hoarding disorder and Its treatment. Behaviour Therapy, 56(4).

- Tolin DF, Meunier SA, Frost R et al (2010) Course of compulsive hoarding and its relationship to life events. Depression and anxiety, 27(9), 829-838

- Tompkins MA (2015) Clinician's guide to severe hoarding: a harm reduction approach. Springer

- Verkerk EW, Tanke MAC, Kool RB et al (2018) Limit, lean or listen? A typology of low-value care that gives direction in de-implementation. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 30(9), 736-739

- Vogel D and Wade N (2009) Stigma and help-seeking. British Psychological Society.

- Ward-Ciesielski E and Rizvi SL (2021) The potential iatrogenic effects of psychiatric hospitalization for suicidal behavior: a critical review and recommendations for research. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 28(1), 60–71.

- Woody S and Bratiotis C (2024) Home Environment Assessment Tool for Hoarding (HEATH©). University of British Columbia’s Centre for Collaborative Research

- Worden BL and Tolin DF (2022) Co-occurring obsessive-compulsive disorder and hoarding disorder: A review of the current literature. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36(4).

- World Health Organisation (2022) International classification of diseases (11th Revision) (Vol. 2024)

About the authors

Linda Fay, MSc, is the founder of Hoarding Academy and author of ‘A Pragmatic Approach to Chronic Disorganisation and Hoarding – using the DESIRE method’. In 2015, she became the UK’s first practitioner to receive Specialist level certificates in Chronic Disorganisation and Hoarding Disorder. Linda is a steering group member of the UKHD Partnership and the Hoarding Research Group and instigator of Scotland’s Hoarding Taskforce.

Katherine Parsons, PhD, is a Lecturer in Behaviour Change and Implementation Science at Aberystwyth University. Her research focuses on health behaviour change in underserved populations.

Acknowledgements

This Insight was reviewed by Ashley Campbell (Chartered Institute of Housing, Scotland), Kayley Hyman (Holistic Hoarding), Johanna Johnston (North Lanarkshire, Adult Protection), Heather Matuozzo (Clouds End CIC), Prof Nick Neave (Northumbria University), Barbara Potter (Clutter Chat), and Dr Stuart Whomsley (Northamptonshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust) with feedback from colleagues in Scottish Government. Comments represent the views of reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of their organisations.

Iriss would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time to reflect and provide feedback on this publication.

Credits

- Series Coordinator: Kerry Musselbrook

- Commissioning Editor: Kerry Musselbrook

- Copy Editor: Kerry Musselbrook

- Designer: Ian Phillip