Key points

- The PREVENT policy raises questions about the changing nature of the social work role, with evidence highlighting ways in which social work is being drawn into policing, surveillance and pre-crime work.

- Referral data shows that it is disproportionately young Muslim men who are being referred to PREVENT. Such referrals reinforce and perpetuate stereotypes about the association of Islam with terrorism.

- Encouraging social workers to explore and question the underlying assumptions made within the PREVENT policy, particularly in relation to race and religion, can help social workers to challenge discriminatory practice and resist the co-option of social work into potentially oppressive policies.

- Understanding and recognising whiteness as at the core of social work histories, knowledge and practice is crucial in decentring it. Incorporating an intersectional approach (Crenshaw, 1989) can help practitioners to reclaim a social justice-oriented social work practice and uphold anti-oppressive and anti-racist values.

Introduction

Addressing and understanding the risks of radicalisation and extremism has been an important and continually evolving area within social work practice. Knowledge and awareness of the types of radicalisation has increased over time, with shifts from predominantly Islamist concerns to inclusion of extreme right-wing or mixed, unstable and unclear ideologies. Equally the space where radicalisation occurs has changed: from more typical social work intervention within the family towards online forums that require Contextual Safeguarding approaches (Firmin, 2020). Social work in this area operates in a ‘pre-criminal’ space, identifying those vulnerable to radicalisation and offering them preventative support.

Awareness of radicalisation and extremism was brought into the remit of social work through the PREVENT policy, part of the counter-terrorism strategies which were designed by the Home Office following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York and the 7/7 bombings in London. However, it was not until 2015 that PREVENT was placed on a statutory footing, requiring social workers to be involved in its implementation.

Significant research has been undertaken on what makes people more likely to be susceptible to radicalisation (Clemmow and Colleagues, 2021; Bhui and Colleagues, 2014) and how this is currently being addressed within social care (Department for Education, 2021). However, there has not been much exploration of the impact that counter-terrorism work has had on the social work role or analysis of how the racial and religious dynamics associated with radicalisation affect practice. This Insight, mindful of the Scottish Association of Social Work’s recent assertion (2022) on the importance of raising consciousness of racism, intends to promote discussion and reflection. In engaging with the underlying racist assumptions within radicalisation policy it is possible to understand their influence upon practice, and help practitioners consider ways to uphold anti-oppressive and anti-racist social work values.

The background

The policy context

In 2003, the UK Government produced its official counter-terrorism strategy known as CONTEST, which is divided into four areas: Prevent, Pursue, Protect and Prepare. At this time the PREVENT strand was aimed at stopping people from supporting violent extremism, with a focus on the threat from Islamist armed groups such as al-Qaeda. The policy has subsequently moved through various iterations. In 2011, after significant criticism, the strategy’s scope was widened to include threats from all forms of armed groups, including right-wing groups. It has also incorporated non-violent extremism into its remit.

In 2015 the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act placed statutory duties on a range of public institutions to actively promote ‘British Values’ and to ‘have due regard to people being drawn into terrorism’ (Section 26 of the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act, 2015). To meet this PREVENT duty, practitioners in specified authorities, including librarians, teachers, doctors, prison officers and social workers must ‘help prevent the risk of people becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism’ (HM Government, 2023 p7). Having ‘due regard’ is typically seen as another safeguarding responsibility that requires making a referral to the PREVENT team. Social workers in both Children and Families teams and Adult Services may have an additional role after referral in assessing the risk of radicalisation as well as being part of ongoing casework. This could include attending and contributing to multi-agency meetings known as Channel panels, that provide specialist support to those considered to be at risk of radicalisation.

Similarities and differences across the UK

With the notable exception of Northern Ireland, PREVENT applies across the UK. However, many policies are specific to England and Wales, and do not apply to Scotland. For example, there are no PREVENT priority areas in Scotland – local authority areas where risk of radicalisation or extremism is deemed higher – or a requirement to teach ‘fundamental British values’ within schools (HM Government, 2015 p41). Additionally, Channel panels in England and Wales are called PREVENT Multi-Agency Panels in Scotland, albeit they carry out the same role.

That said, one of the recommendations within the Independent Review (2019) of PREVENT is that the Scottish Government should restructure Scottish PREVENT in line with the regionalisation model for England and Wales. This recommendation has been accepted by the Home Secretary, and is likely to impact upon social work practice in Scotland.

Divergent reviews

An Independent Review of PREVENT was commissioned in 2019 and published in 2023. A group of 17 major human rights organisations and over 500 mainly Muslim civil society organisations and experts boycotted this review, creating their own submission of evidence and collating a People’s Review of PREVENT (2022). The reports drew significantly different conclusions, and while neither directly focused on the social work role, both have relevance to its practice. For example, the Independent Review reported that emphasis on vulnerability should be reduced; that attention should be refocused on countering non-violent Islamic extremism. In contrast, the People’s Review suggested that the PREVENT policy is discriminatory and undermines safeguarding responsibilities.

The key terms used within the aforementioned policies namely terrorism, extremism and radicalisation are important and have been criticised for lacking clear definition (Faure Walker, 2021). The UK defines extremism as ‘vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs [as well as] calls for the death of members of our armed forces’ (HM Government, 2011 p107). The subjective notion of ‘British values’, has the potential to bring a wide variety of behaviours into the PREVENT remit. Equally radicalisation is also defined vaguely, as ‘the process by which a person comes to support terrorism and forms of extremism leading to terrorism’ (HM Government, 2011 p108). These definitions also emphasise the pre-criminal role of PREVENT.

Referrals to PREVENT – what the data tells us

The Home Office releases data each year on the number of referrals received, the sectors making the referrals and how many are adopted at a Channel panel. They also release demographic data such as the age, gender and type of concern for those referred to and supported through the PREVENT programme. In the year ending 31st March 2022, the statistics for England and Wales (HM Government, 2023) revealed that there were 6,406 referrals to PREVENT in England and Wales, a 30% increase on the year before. 89% of referrals were for males and of the referrals where the age of the individual was known, those aged 15 to 20 accounted for 30%, the largest proportion. However, those under 15 years of age saw the most significant increase: 29% compared to 20% the year before. These findings have had significant impact on the analysis undertaken in the People’s Review of PREVENT (2023) and in a report by the Child Rights International Network [CRIN] (2022) it states that this focus on children puts policing priorities above their rights.

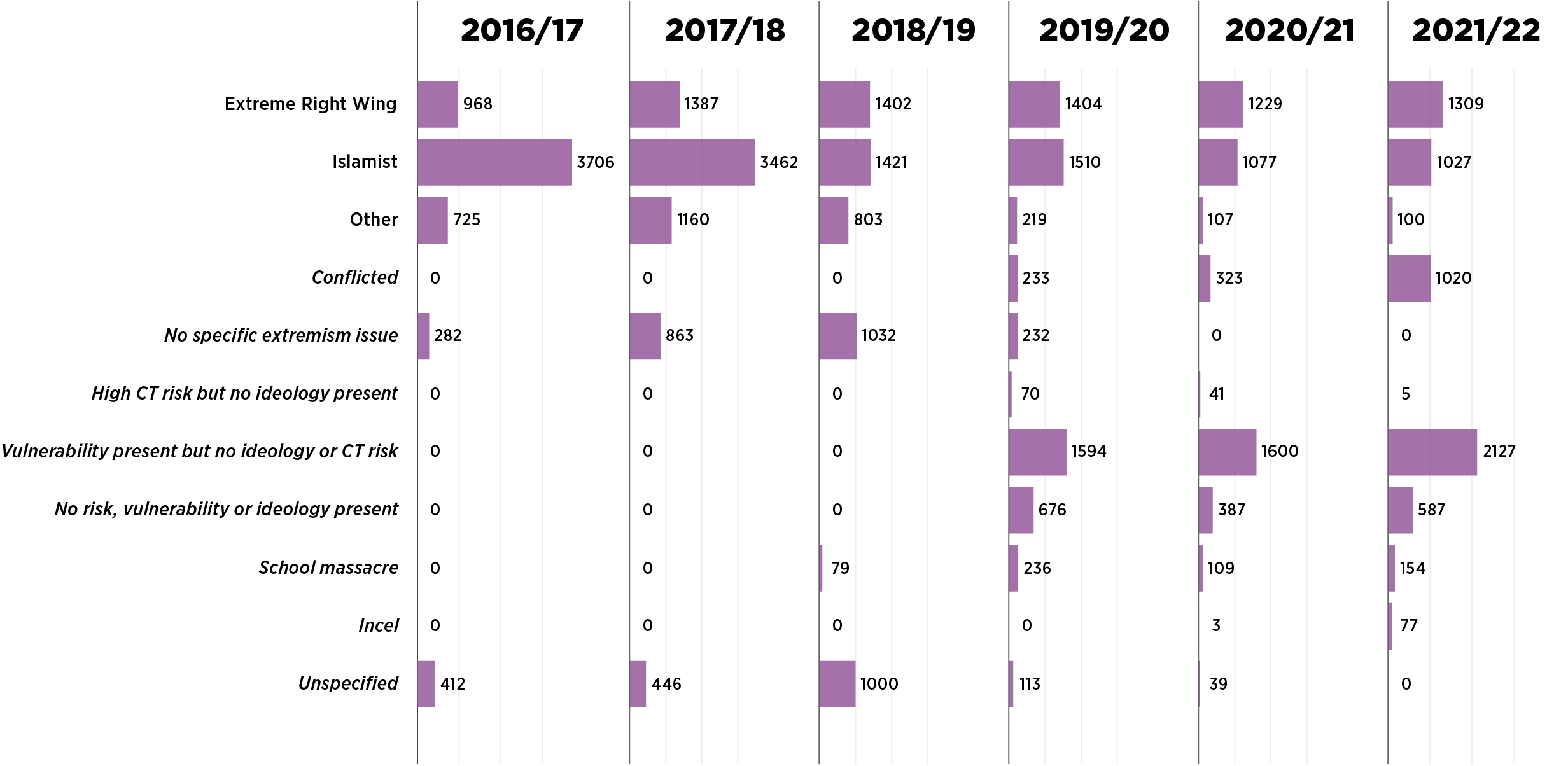

The Home Office PREVENT statistics do not address religion, ethnicity or class, however they do indicate the type of concern which gives some suggestion of religious beliefs, particularly with regards to Islamist extremism concerns. Figure 1 shows how the type of concern has changed over time, with higher numbers for those associated with the extreme right wing than Islamism since 2020/21. This has been used to dispute claims that the policy is discriminatory towards Muslim communities (Policy Exchange, 2022), suggesting that everyone is susceptible to radicalisation and discounting the racialised effects of power (Winter and Colleagues, 2021). However, according to the Office for National Statistics (2021), only 6.5% of the population in England and Wales identify as Muslim, yet Islamist concerns account for 16% of concerns. As such, it would seem that young Muslim men experience PREVENT disproportionately and more intensively than their white counterparts.

However, the Independent Review (2023 p7) refutes this interpretation of the data or the suggestion that PREVENT is ‘out of kilter with the rest of the counter-terrorism system… [because] Islamist extremism represents the primary terrorist threat to this country.’ This represents the argument that the targeting of Muslim communities is a ‘measured response’ and thus proportionate to the threat (Patel, 2017a p3). The statistics, and the response to them, both challenge and highlight the assumptions that underlie the PREVENT policy.

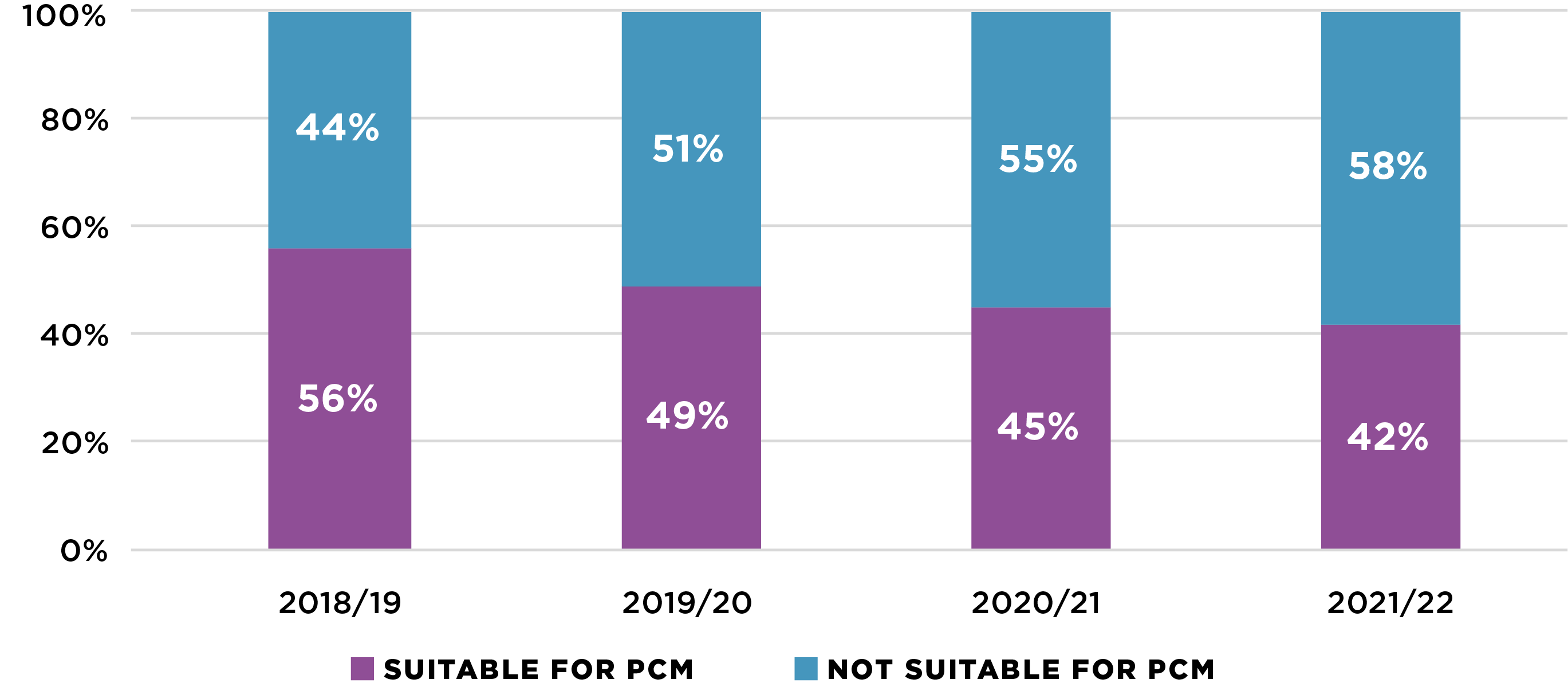

In Scotland, there are a significantly lower number of referrals than in England and Wales. There were 91 referrals in 2021/22, which was an increase of 65% on the previous year (Police Scotland, 2023). Akin to England and Wales the majority of referrals are for males aged 15-20. However not all of these referrals are suitable for PREVENT case management. In England, Wales and Scotland there is a wide disparity between the number of people referred to PREVENT versus the number that are accepted as part of Channel or PREVENT Multi-Agency Panels. Medact (2020) terms these ‘false positives’, which represent the extension of services into people’s lives without proportionality (HM Government, 2023). This can be seen within Figure 2, providing Scottish data, but also indicative of the disparities across the UK.

The evidence suggests that in Scotland the most common type of concern relates to mixed, unstable or unclear ideology, followed by right-wing radicalisation. Regardless of the few referrals relating to Islamist extremism in Scotland, the UK-wide PREVENT duty contributes to the construction of Muslim populations as ‘suspected communities’ (Pantazis and Pemberton, 2009 p646), and impacts upon how Muslims are viewed across the world. While there are also classist undertones to who is drawn into the remit of PREVENT, this Insight focuses predominantly on the significant impact upon Muslim communities.

The role of race and religion

The intersection of race and religion are important to any discussion of the PREVENT policy. Counter-terrorism policies, justified on the grounds of national security, connect race and culture with national identity and community cohesion (Patel, 2017b). In this way, categories of ‘us’ and ‘them’, ‘victim’ and ‘suspect’ are defined along racial and religious lines (El Enany, 2020).

Racism and its associated discriminations are not individual biases but are, rather, built into our social relationships and structural practices, linked to the cultural legacy of colonialism and imperialism. In Scotland, the inquiry undertaken by the Cross-Party Group on Tackling Islamophobia reported that it ‘recognises Islamophobia as a form of anti-Muslim racism that targets Muslims and those who are misrecognised as Muslims’ (Hopkins, 2021 p10). Sayyid (2014:14-19) emphasises the intersection between race and religion by suggesting that Islamophobia involves the regulation of Muslims in relation to Western norms and standards. It is necessary, therefore, to understand Islamophobia in the context of whiteness, which Cancelmo and Mueller (2019) describe as a social phenomenon that is maintained through various institutions, ideologies and everyday practices.

We know from research by the Scottish Association of Social Work (2021) that racism exists within social work in Scotland. This can be exemplified starkly in a PREVENT context by the promotion of ‘British Values’ which acts as a synonym for whiteness. And while social work interventions focus on the causes of radicalisation and the effectiveness of intervention, racialised assumptions that shape the PREVENT policy go unquestioned (Yassine and Briskman, 2019). Further, understanding how the institution works to disadvantage those from non-Western racial and religious backgrounds is clearly important if we want to recognise and address the racism inherent within the profession.

What are social workers being asked to do and what are the implications of this?

Radicalisation is a complex and continually evolving area with practitioners tasked with translating this high-level counter-terrorism policy into practice and what this means for intervention with specific service users. Importantly, this Insight does not reflect upon individual practice but rather focuses on PREVENT as a political practice, with the potential to change the social work role.

Securitisation

The duty for specified authorities to ‘have due regard’ aligns with the process of securitisation. This describes something deemed a concern being constituted as a security issue, requiring use of extraordinary measures to monitor and contain the risk (Buzan and Colleagues, 1998). PREVENT operates in a ‘pre-crime’ space, allowing imagined future risk to produce particular forms of intervention, such as increased levels of surveillance through extra multi-agency meetings or an additional intervention provider. Within this structure social workers move from more collective notions of welfare towards more risk-averse, personalised and individualistic approaches (Finch and McKendrick, 2019). A result of the pre-criminal nature of PREVENT is that the assumptions that underlie the policy – which link being Muslim with being a terrorist – have justified extension of surveillance into every part of Muslim’s life from clothing to prayer (Yassine and Briskman, 2019). This is reinforced by the CRIN report (2022) which states that ‘PREVENT’s monitoring of children’s lawful behaviour for signs of ‘extremism’ and ‘radicalisation’ interferes with their rights to privacy and to freedom of expression, religion and assembly.’ This is a direct contravention of the Equality Act 2010.

Social workers or police?

Racialised surveillance of ethnic minority groups has long been part of policing practices (Browne, 2015) and has been described as a technology of social control. The CRIN report (2022) suggests that PREVENT, encouraging such surveillance, violates children’s rights by putting policing before children’s welfare. Thus, relationships of care and trust, on which social work depends, are being surpassed by relationships of surveillance (Wroe and Lloyd, 2022). This suggests that the boundaries between the role of the social worker and the role of the police are being blurred.

The language of safeguarding is used to embed radicalisation within practice (Kaleem, 2022) and to separate it from national security. This depoliticises counter-terrorism work and encourages a focus on individual actions and beliefs, without addressing the ‘underlying conditions conducive to children’s exploitation’ (CRIN, 2022 p22). Whilst using the language of safeguarding, rights appear to be overridden and vulnerable people are drawn into contact with social care and the police. In this way social workers are part of the processes that maintain ‘law and order’ (Savage, 2010 p171) – something typically associated with the police.

From vulnerable person to risky individual

The PREVENT space requires social workers to address tensions between safeguarding individuals vulnerable to radicalisation and safeguarding the general public by identifying risky people. This is emblematic of a wider debate in social work between care and control (Hardy, 2015). Practice within this area tends to be risk-averse. For example, the People’s Review of PREVENT (2022 p47) details a case where a school was worried about a Muslim young person’s views after he wrote ‘Muslims are better than Christians’ on a drawing of a mosque. The case was referred to a social worker to assess the risk of radicalisation, who asked questions about a protest that the parent and child had attended. This questioning then led to a referral to the PREVENT team, which would likely have meant further involvement for this family and reinforcement of the view that Muslim communities are threatening.

Counter-terrorism interventions such as PREVENT are overwhelmingly targeted at young Muslim men (Yassine and Briskman, 2019), who are suspected of and need saving from extremism. Coppock and McGovern (2014) explain that the construction of ‘risky’ Muslim identities rests on the longer term pathologisation and imagined threat of Muslim masculinities, where social and cultural problems have become psychological ones. Gillian (2009) observes that social workers are not immune to the pervasiveness of these discourses. The People’s Review of PREVENT (2022 p82) reiterates this by expressing that social workers play a role in taking ‘the signs among young people of ordinary identity development and explorations in belonging as indications of ‘riskiness’, as well as sanctioning their activism’.

In addition to risky individuals, particular local authorities are set apart as PREVENT Priority Areas. There is no readily available information which explains the criteria for becoming a PREVENT Priority Area however the People’s Review of PREVENT (2022) identified that these are home to predominantly Muslim communities. As highlighted, proponents of PREVENT believe that this is a ‘measured response’ (Patel, 2017a), acting as a justification for the focus upon these communities. In this way the underlying assumptions are forgotten, and rather than unpacking the racial understandings behind the PREVENT policy, the focus is placed upon risk with impetus for social workers to act.

The issue of thresholds

An issue brought to light by the Association of Directors of Children’s Services [ADCS] (2015) in England is ‘the difficulties in knowing where exactly the thresholds for intervention lie – when does parenting style, or the holding of particular beliefs, become a child protection issue?’ As radicalisation encompasses a wide range of activities and is seen less frequently than other forms of harm, this can be a challenge. Lavalette (2013) highlights concerns that a lack of knowledge about Islam leads to increased referrals of Muslim people. This includes where practitioners view Muslim values as being in opposition to British values, such as around respect for women and LGBTQIA+ rights. Imprecise definitions of extremism, misunderstanding the Muslim community and their religious and cultural practices and an atmosphere of institutionalised Islamophobia combine to target these communities.

The lack of consistency within thresholds across ideologies and types of radicalisation was something addressed in the Independent Review of PREVENT (2023), which stated that PREVENT has a double standard when dealing with the extreme right-wing and Islamism. The reviewer commented that this should be rebalanced, leading to a higher number of Islamist PREVENT referrals in line with this being the primary terrorist threat. In contrast to this the People’s Review (2022) argues that guidance, training and application of PREVENT are all enforced more aggressively with regards to Islamist extremism and less punitively for far-right extremism. This argument refutes the view that Britain is post-racial and highlights the importance of the racial assumptions underpinning PREVENT. The Scottish Association of Social Work (2021) indicates how the view that Britain is post-racial obscures racism as an issue of fundamental importance. Practitioners are thereby distanced from these forms of discrimination which leads to further normalisation and embedding of white norms (Ali, 2020).

Is social work at risk of aligning itself with injustice, inequality and racism?

Through raising questions about the relationship between the PREVENT policy and the social work role, it is apparent that there are significant tensions between the policy and social work values of anti-oppressive, anti-discriminatory and anti-racist practice. From putting policing priorities over those of welfare to thresholds influenced by the public perception of Muslim people, it is apparent that the basic values in social work, based on ‘respect for the equality, worth and dignity of all people’ (BASW, 2021) are at risk.

The Cross-Party Group on Tacking Islamophobia report (2021 p36) is damning of PREVENT: ‘Given the weight of evidence against PREVENT, schedule 7 and related counter-terrorism legislation, the Scottish Government should take steps to encourage the withdrawal of these and related strategies.’ Such policies through their racialised assumptions and prejudicial practices represent ‘whiteness at work’ (Yassine and Briskman, 2019), prioritising white knowledge and ways of being while perpetuating further discrimination against minoritised racial and religious groups.

Despite these difficulties, understanding tensions within the social work role allows for proposals of how social work can comply with its statutory duties at the same time as locating and overturning discriminatory practices. For example, in accordance with the Medact (2020) report, the Independent Review of PREVENT (2023 p8) indicated that ‘PREVENT is carrying the weight for mental health services. Vulnerable people who do not necessarily pose a terrorism risk are being referred to PREVENT to access other types of much-needed support.’ This indicates that social workers, with awareness of contemporary difficulties within a system affected by austerity and scarcity of resources, are using this policy to advocate for those they are working with, showing a commitment to social justice (Ferguson and Lavalette, 2013).

Implications for the social service workforce

Through the commitment to social work values and ethics social workers have a responsibility to challenge racism and to be attentive to the lived experience of those they work with. The PREVENT policy represents a real challenge for social workers between understanding the importance of safeguarding vulnerable people from various forms of exploitation and not being co-opted into policies that are discriminatory in nature.

In line with the Scottish Association of Social Work (2022) action plan, recognising that race inequality and racism are central features of the social care system is fundamental to social work being able to take a truly anti-racist stance. Incorporating the concept of ‘intersectionality’ (Crenshaw, 1989) further into the profession may have some purchase, in order to bring attention to forms of power and oppression based on multiple and overlapping identities. Using this concept requires social workers to address their own practice and reflect on the ways in which whiteness is embedded into it (Tascón and Ife, 2020). It could also be used to consider other minoritised communities who are also referred disproportionately to PREVENT including those who have mental health issues or are neurodivergent.

Social work needs to re-harness its history of social justice in order to re-establish itself as a profession of resistance that can challenge racism and Islamophobia. Understanding whiteness as at the core of social work histories, knowledge and practice is fundamental to decentring it (Tascón and Ife, 2020). For PREVENT this could look like challenging the involvement of social workers within the PREVENT duty, in order to reject oppressive practice.

References

- Association of Directors of Children’s Services [ADCS] (2015) ‘A briefing note on the radicalisation of children, young people and families’

- Ali N (2020) ‘Seeing and Unseeing Prevent’s Racialized Borders.’ Security Dialogue 51 (6): 579–596

- Amnesty International (2023) ‘UK: Shawcross review of PREVENT is ‘deeply prejudiced and has no legitimacy’’

- BASW (2021) ‘The Code of Ethics for Social Work’

- Bhui K, Everitt B and Jones E (2014) ‘Might Depression, Psychosocial Adversity, and Limited Social Assets Explain Vulnerability to and Resistance against Violent Radicalisation?’ PLoS ONE 9(9): 1-10

- Browne S (2015) Dark Matters: On the surveillance of Blackness. Durham: Duke University Press

- Buzan B, Waever O and Wilde JD (1998) Security: a new framework for analysis. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers

- Cancelmo C and Mueller J (2019) Whiteness. Oxford Bibliographies

- Clemmow C et al (2023) ‘The Whole is Greater than the Sum of its Parts: Risk and Protective Profiles for Vulnerability to Radicalisation.’ Justice Quarterly 1-27

- Coppock V and McGovern M (2014) ‘Dangerous Minds? Deconstructing Counter-Terrorism Discourse, Radicalisation and the ‘Psychological Vulnerability of Muslim Children and Young People in Britain’ Special Issue: Psychiatrised Children and their Rights: Global Perspectives, 28(3), 242-256

- Crenshaw K (1989) ‘Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics’. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139-167

- Child Rights International Network [CRIN] (2022) ‘Preventing Safeguarding: The Prevent strategy and children’s rights .’

- El Enany N (2020) (B)Ordering Britain: law, race and empire. Manchester: Manchester University Press

- Faure Walker R (2021) The Emergence of ‘Extremism’: Exposing the Violent Discourse and Language of ‘Radicalisation’. Bloomsbury: London

- Ferguson I and Lavalette M (2013) ‘Crisis, austerity and the future(s) of social work in the UK’. Critical and Radical Social Work, 1(1), 95-110

- Finch J and McKendrick D (2019) ‘Securitising social work: Counter terrorism, extremism and radicalisation’ in S. Webb (ed). The Routledge Handbook of Critical Social Work. London: Routledge

- Gilligan C (2009) ‘Highly Vulnerable? Political Violence and the Social Construction of Traumatized Children.’ Journal of Peace Research, 46(1): 119-134

- Gillborn D (2005) ‘Education policy as an act of white supremacy: whiteness, critical race theory and education reform’. Journal of Education Policy 20(4): 485-505

- Goldberg D (2015) Are we all Postracial yet? Cambridge: Policy Press

- Hardy M (2015) Governing Risk: Care and Control in Contemporary Social Work. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

- HM Government (2011) ‘PREVENT strategy’

- HM Government (2015) ‘Counter-Terrorism and Security Act’

- HM Government (2015) ‘Prevent duty guidance: England, Scotland and Wales’

- HM Government (2021) ‘Revised Prevent Duty Guidance: For England and Wales’

- HM Government (2023) ‘Official Statistics: Individuals referred to and supported through the Prevent Programme, April 2021 to March 2022’

- HM Government (2023) ‘Prevent duty guidance: Guidance for specified authorities in England and Wales’

- Holmwood J and Aitlhadj L (2022) ‘The People’s Review of PREVENT’

- Hopkins P (2021) Scotland’s Islamophobia: report of the inquiry into Islamophobia in Scotland by the Cross-Party Group on Tackling Islamophobia. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Newcastle University

- Kaleem A (2022) ‘The hegemony of Prevent: turning counter-terrorism policing into common sense’. Critical Studies on Terrorism 15(2): 267-289

- Kundnani A (2014) The Muslims are coming! Islamophobia, extremism and the domestic war on terror. London: Verso

- Langdon-Shreeve S and Nickson H (2021) ‘Safeguarding and radicalisation: learning from children’s social care’. Department for Education

- Lavalette M (2013). ‘Institutionalised Islamophobia and the ‘Prevent’ agenda: ‘winning hearts and minds’ or welfare as surveillance and control?’ In Lavalette, M. and Penketh, L. (Eds.) Race, Racism and Social Work

- Medact (2022) ‘False Positives: the PREVENT counter-extremism policy in healthcare’

- Office for National Statistics (2023) ‘Religion by age and sex, England and Wales: Census 2021’

- Pantazis C and Pemberton S (2009) ‘From the “old” to the “new” suspect community: Examining the impacts of recent UK counter-terrorist legislation’. British Journal of Criminology, 49 (5): 646–66

- Police Scotland (2023) ‘Prevent Referral Data, Scotland, April 2021 to March 2022’Policy Exchange (2022) ‘Delegitimising Counter-Terrorism: The Activist Campaign to Demonise Prevent’

- Patel T (2017a) ‘It’s not about security, it’s about racism: counter-terror strategies, civilizing processes and the post-race fiction’. Palgrave Communications, 3

- Patel T (2017b) Race and Society. Sage: London

- Police Scotland (2020) ‘Prevent Referral Data’

- Police Scotland (2023) ‘Prevent Referral Data’

- Savage S (2010). ‘Tackling tradition: Reform and modernization of the British police’. Contemporary Politics, 9, 171-184

- Sayyid S (2014) ‘A measure of Islamophobia’. Islamophobia Studies Journal, 2(1): 10-25

- Scottish Association of Social Work (2021) ‘Racism in Scottish Social Work: a 2021 snapshot’

- Scottish Association of Social Work (2022) ‘SASW Anti-Racism Plan’

- Shawcross W (2023) ‘Independent Review of Prevent’

- Tascón S and Ife J (2020) Disrupting Whiteness in Social Work. New York: Routledge

- Winter C et al (2022) A moral education? British Values, colour-blindness, and preventing terrorism. Critical Social Policy, 42(1), 85–106

- Wroe L and Lloyd J (2022) ‘Watching over or Working with? Understanding Social Work Innovation in Response to Extra-Familial Harm.’ Social Sciences, 9(4)

- Yassine L and Briskman L (2019) Islamophobia and social work collusion. In D Baines, B Bennett, S Goodwin, & M Rawsthorne (Eds.), Working Across Difference: Social Work, Social Policy and Social Justice (pp. 55-70)

About the author

Sophie Shall is a registered social worker and PhD student at Glasgow Caledonian University. Sophie is undertaking interpretive sociological research exploring the relationship between the Prevent policy and social work. Sophie is particularly interested in the role of power within social work and understanding how interlocking oppressions impact upon service users. Prior to doctoral studies, Sophie worked in Referral and Assessment within the Children and Families service in a London borough.

Acknowledgements

This Insight was reviewed by Jo Finch (University of Suffolk), Kamal Ibrahim (Practitioner), David McKendrick (Glasgow Caledonian University), and Scottish Government colleagues from the Office of the Chief Social Work Adviser and others from Health providing an equalities perspective.

Comments represent the views of reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of their organisations. Iriss would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time to reflect and provide feedback on this publication.

Credits

Series Coordinator: Kerry Musselbrook

Commissioning Editor: Kerry Musselbrook

Copy Editor: Stuart Muirhead

Designer: Ian Phillip