Part two of the report highlights key themes explored in workshops, before going on to outline the six key principles for great recording. The themes arose from practitioner ideas about what they wanted to focus on within their tests of change as well as from Iriss-led activities. The three overarching themes we cover are:

- Connecting with the person and personal experience

- Making information in case notes clearer and more accessible

- Improved evidencing of decision-making

In each theme we look at main points raised in the workshops, emerging outcomes from practitioners’ tests of change and their reflections on the testing process.

Connecting with the person and personal experience

A core thread running through the workshops was making recordings more inclusive and accessible — thinking of the future reader — the person who might access and read their records at a later stage in life. This section gives highlights of how we approached this and what we found.

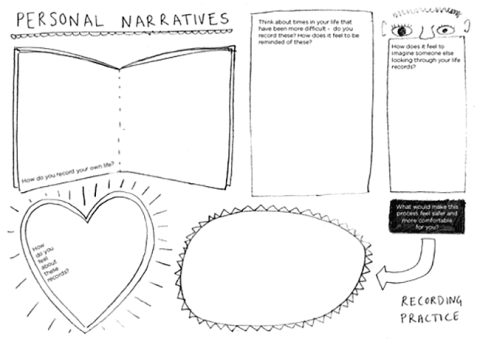

We started exploring the topic in Workshop One by reconnecting with the personal experience and values behind recording. What do we record in our own lives when it comes to both the happy and the hard times? What does it, or would it, feel like when other people see what is recorded about us? What role does the element of choice play in what we share or don’t share with others? We then followed on to reflect on making recordings with the person at the centre — how do practitioners do that? What works well? What’s difficult?

Reflections on the content of case notes

- Think about using language that isn’t stigmatising or traumatising

- What is it like to read all those things about your life (a collection of your case records) sitting on your own? Be present to look at recordings together rather than alone, where someone can help to explain about how services work or answer questions.

- “It’s not our (practitioners) data, it’s other people's information. Practitioners should do more to promote data and records access and ownership. Explain what is recorded and why to people”.

- The chronology is the place for documenting significant events, however it’s not always straightforward where the most suitable place for recording certain details will be. E.g. Some people felt strongly that it was important to record somewhere that multiple attempts to visit a family had been made by an agency to show that someone was trying to provide support. This could be really important for someone reading their case record in later life and understanding more about their childhood.

- Writing from a risk management perspective and using jargon and acronyms can be barriers to making a case note that shows the person at the centre.

What works well already for practitioners

- Record what’s gone well not only what's negative — e.g. in Children’s Houses the ‘My Day’ format supports a more holistic record of the day. It was recognised this format is not suitable for shorter meetings or other interventions but that guiding principle can be applied to any recording.

- Be descriptive but not judgemental

- “While tools are important, the relationship is essential. Listening, taking time, 1 to 1, and having more regular contact helps to establish the relationship”.

- See people in different settings if possible

- Using Getting It Right For Every Child policy (GIRFEC) and associated Wellbeing indicators (SHANARRI: Safe, Healthy, Achieving, Healthy, Nurtured, Active, Respected, Responsible, Included)

- Naming the person rather than calling them a service user. Using names is now more common practice across agencies and services rather than 10 or 20 years ago. Records need to be personal.

Case notes are more person centred: tests of change

Tests of change showed signs of shifting the balance in case notes towards writing in a way that prioritises the voice of the person being worked with and finding ways to emphasise that the case note is first and foremost about, and for, them, rather than the worker. Emerging outcomes suggest a positive ripple effect for some practitioners of increasing reflexivity about the content that went into the case note and how that was generated and then written up. The table below presents actions and emerging outcomes from group members who tested out ways to make their case notes more person-centred. This includes focusing on:

- Naming

- Changing the style of writing

- Reflecting before writing

- Including the young person’s point of view

A number of people tested out the same idea so their actions and observations were summarised collectively.

Emerging outcomes from tests of change

|

Anticipated outcome: Case notes are more person-centred |

Action tested out |

Practitioner observations and emerging outcomes |

|---|---|---|

|

Naming |

Using given names instead of ‘mum’, ‘baby’ or ‘service user’ |

Actions and outcomes are more clearly linked to the person — individualised Shows that the practitioner knows who the person in the case note is — not just an anonymous client |

|

Style of writing |

Writing a ‘letter to’ |

Feels like analysis is stronger than before because it is weaved into the account of what happened. Feels like it’s honest and shows relationship between worker and young person Needs to be shared with young person for feedback as a next step |

|

Reflecting before writing |

Taking time to pause and picture the child being written about before starting to write |

Case note was more focused on the child rather than parents or siblings Feels more aware of what I was recording and how Found this encouraged more reflective conversations with peers |

|

Including young person’s point of view |

Making time to discuss this with the young person |

Notes feel more co-produced but isn’t always easy to do |

Reflections from practitioners testing changes to make case notes more person-centred

What helped you to test these changes?

- Thinking more about language and content

- Taking time

- Getting other colleagues on board

What will help you to continue doing this?

- Inspiration in our culture to do so

- Permission to take time to improve

- Focus on involving people (colleagues) who are prepared to change

- Being brave

Recommendations for other practitioners trying this out:

- Think of your future reader

- Accept there will be different writing styles

- Aim to get a balance of focusing on the person and analysis

Making information in case notes clearer and more accessible

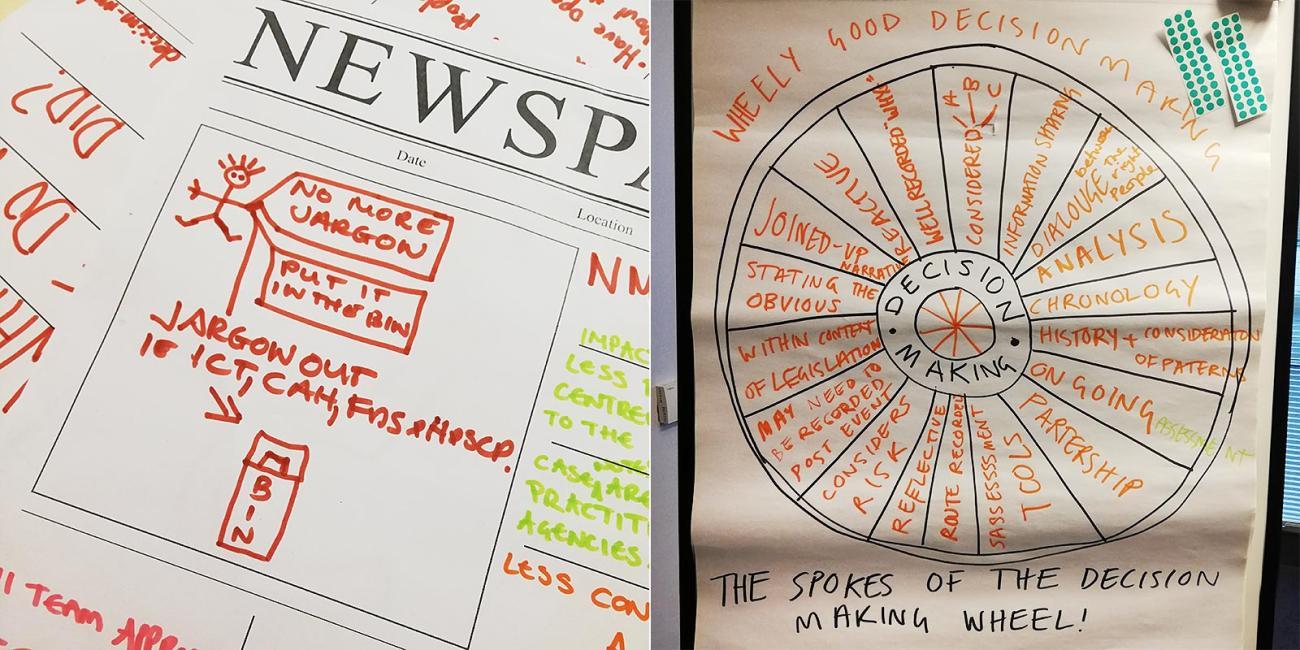

This topic was interwoven with discussions about the experience of someone reading their case records in the future and ‘writing forward’ with that experience in mind. However, it was also relevant for the present day in relation to making records more accessible for other practitioners to read and use. What we found in discussion of the tests of change is that when some practices make key information harder to find within a recording, they can effectively be ‘reset’ by taking a team approach to change. Changes to practice that people tested out include:

- Addressing how acronyms or jargon are used

- Ways to make content more succinct

- Improving use of chronologies

The table below gives more details about what people tested out and the emerging outcomes. Some people chose to focus on their approach to producing chronologies as a starting point to examine how and what they record, and in what format, while others looked more closely at language use and evaluating where information could usefully be removed from a case note. These tests of change highlighted that almost immediately there were visible impacts on improved information sharing and clarity of what was being communicated between colleagues in teams and, in some cases, across services.

Emerging outcomes from tests of change

|

Anticipated outcome: Information is clearer and more accessible |

Action tested out |

Practitioner observations and emerging outcomes |

|---|---|---|

|

Addressing how acronyms or jargon are used |

Remove acronyms, or if using an acronym explain in full the first time used in the case note. Avoid jargon — but give an explanation in Plain English if it is unavoidable. |

Colleagues found the notes easier to understand Support needs for the individual are clearer to see Questions from partner agencies related to the case note have reduced Feels like there’s less risk when the notes are clearer to understand for all. Should be clearer for the future reader to understand |

|

Content is more succinct |

Not repeating information in the case note about referrals already provided elsewhere in the record Removing ‘cut and paste’ parts of emails chains |

Colleagues say the note is clearer and more relevant |

|

Improved use of chronologies (from Health Services perspective) |

|

Practitioner feels that information provided is more focused on relevant details and clearer definition between case note and chronology Safer for families and Child Protection if all the information is updated promptly Better multi agency information sharing |

Another support for improved clarity was discussed more widely in connection to a change to a new Social Work electronic case management system (Liquid Logic). Having the facility to finalise a note at a later time allows for crucial information to be inputted very shortly after a contact, but then other details and analysis can be reviewed and refined when the practitioner has had time for their thoughts to settle and reflect.

The additional reflections below suggest that successful upscaling and embedding of these ideas would require buy-in and agreement within and across service groups alongside smaller scale team-based approaches.

Reflections from participants testing ideas to make information in case notes clearer and more accessible

What helped?

- Full team approach

- Support from colleagues

- Making a more conscious effort

- Being allowed more time to write

- New systems allow for finalising the case note later after the first input

- Chronology reminders at team meetings, post it on computer

- AYRShare [1] — for sharing with partner agencies

What will help you to continue doing this?

- Teamwork

- Continuing to revisit and reflect — it can be hard to break habits

- Getting partner agencies on board

- Completing chronologies as soon as possible

Recommendations for other practitioners trying this out:

- Keep hold of why it’s important to do this and allow time

- There’s a risk of reverting back to old ways in light of increased pressures if you don’t have enough resources to maintain this approach

- Remember professional codes and requirements

- Be mindful of confidentiality — e.g. talking about siblings in each other’s notes

Evidencing decision-making

The way in which decision-making is evidenced and included in a case note emerged as a priority for a variety of reasons:

- Managers observed that team members often speak clearly about the purpose and rationale behind their decisions but this can be less well articulated in a case note.

- The details behind complex decisions made during crisis are not always written up in a way that provides useful background information for someone reading their records later in life. This is not to say that decisions are not well articulated in records, but that some of the details that provide deeper context for a person’s life story may not be included. For example, explaining in detail why alternative options were not viable.

- It can be hard to write in depth about the evidence base for a professional judgement or decision in a case note when there is a concurrent demand to make notes succinct.

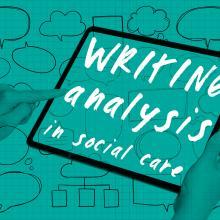

Through activities to identify the key components of decision-making we aimed to uncover some of the tacit processes and practices that are part of this day-to-day work, and explored the question: what and who is involved in decision-making?

Using the visual of a wheel, we created spokes to represent the elements that were identified as part of making and evidencing decisions from a cross-service perspective.

These ‘spokes’ can be further categorised into practices and processes that take place during decision making. Some of these may be a combination of the two

|

Practices |

Processes |

|---|---|

|

|

The group then prioritised some of the aspects that they would value professional development (through further training or other supports like supervision, development days or written guidance):

- Writing up and including analysis in case notes

- Recording the ‘whys’ well

- Stating the obvious (in connection to making notes more accessible and information clear to understand by all readers)

- Showing how options were considered and chosen

- Weighing up and evidencing risk

The elements surfaced in this discussion echoed some of the testing that had been ongoing by some of the participants who had been examining the processes of recording decisions, and can be seen in the table below. These include:

- Analysing how decisions and judgements are written about in the case note

- Showing the alternatives (recording the ‘whys’)

- Case notes and records are more accurate in recording decisions about the behaviours of young people

Emerging outcomes from tests of change

|

Anticipated outcome: The basis for decision making is better evidenced in a case note |

Actions |

Practitioner observations and emerging outcomes |

|---|---|---|

|

Analysing how decisions and judgements are written about in the case note |

Checking back through case notes for fact or opinion and highlighting (creating a visual), to make an analysis of where judgements are well backed up with facts |

It showed the practitioner how professional decisions are not always clearly justified — with the result that they look like opinions. This could be developed as a team activity for critical reflection on how to make the link between facts and judgements stronger. |

|

Showing the alternatives |

Making sure that notes explain what alternatives were considered. e.g. why we went with ‘Plan B’ and why Plan A and C were not possible |

It will give a future reader more understanding why certain things couldn’t be done — children may be told this at the time but they might not remember |

|

Case notes more accurately record decisions |

||

|

Case notes and records are more accurate in recording decisions about the behaviours of young people |

Looking at ways to reduce the frequency of young people in Children’s Homes being recorded as absconders when they are not |

Focus on understanding what is classified as ‘breaking curfew’ and if that is appropriate. Improvements here can lead to more accurate recording in a young person’s record. |

Reflections on testing ideas for evidencing decision-making

What helped?

- Using the question ‘Why did we do what we did?”

- Liquid Logic (electronic case management system) helps by guiding the process

- Put yourself in the shoes of the future reader

What will help you continue doing this?

- Opportunities for feedback e.g. file audits

- Read other people’s work

- Have open conversations

Recommendations for other practitioners trying this out

- Change your perspective — take the long view about what happens now and what it means

- Remember your accountability

Principles for great recording

Bringing our testing and learning to a conclusion in Workshop Three we looked towards our ‘gold standard’ — what does a great case note look like? Building up from paired discussion, to small group and then whole group, we wrote up core elements on sticky notes and mapped these out on the wall. We grouped the stickies as we brought them to the wall before reviewing and identifying key principles for each grouping. These six principles have then been reformulated as questions that can be used as prompts.

Six questions that great case notes answer with a ‘yes’:

- Is the context set out?

- Can it be understood by all?

- Is it person centred?

- Does it ‘show the whys’ behind decision making?

- Is the assessment process clear?

- Is there an action plan?

1 AYRShare is an electronic information sharing system used by the three Ayrshire Councils and NHS Ayrshire & Arran to share information for wellbeing and protection of young people and children among partner agencies.