Key points

- Non-offending carers (NOCs) experience high levels of distress and increased isolation following discovery of their child’s victimisation.

- The correlation between positive mental wellbeing for NOCs and positive outcomes for children is demonstrated throughout the literature. The existing literature evidences that NOCs who are well supported can in turn support their children well.

- Social workers should work alongside NOCs to increase knowledge around child sexual abuse (CSA), its impact on families, and develop a plan to support the child in their recovery that also considers the needs of the family as a whole.

- Recovery from CSA is challenging for all involved: Social workers must develop high levels of reflexivity and emotional intelligence in order to work effectively with families, whilst avoiding burnout. This must be supported through effective supervision and access to professional support where necessary.

Introduction

The reporting rates of child sexual abuse [CSA] in the United Kingdom increase with each passing year, with the most recent statistics from the Lucy Faithfull Foundation (2023) estimating that one out of six children in UK will be victimised by sexual abuse by age 18. As a result, social work services are receiving increasing referrals to work with families affected by CSA. What constitutes CSA and the subsequent legal consequences of offending as enshrined in UK legislation can be found within the Sexual Offences Act (2003). However, each devolved nation has its own definition of activities that are considered CSA within its own respective child protection guidelines (Stop it Now, 2023). In 2016, the Scottish Government launched its Child Protection Improvement Programme (CPIP) that sought to make improvements in all areas of child protection including addressing various different forms of CSA such as trafficking, child sexual exploitation and internet-based offending.

Both recent and historical research indicates that children who have survived CSA have better outcomes and increased resilience when they are well supported by their parents or caregivers following disclosure (Tolledo and Seymour, 2013). However, this support often requires far more from carers than what parental instinct or good intentions can offer particularly when carers too, are adversely impacted by the abuse of their child(ren). They often experience post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression and intense feelings of helplessness and shame in the months and years following disclosure. These adverse psychological repercussions are often exacerbated when the perpetrator of abuse is known to the family (Azzopardi, 2022; Fuller, 2016; Hernandez and colleagues, 2009).

Empirical evidence indicates that to proactively and effectively support their children, non-offending carers [NOCs] need to increase their knowledge about CSA and need support to develop skills to manage the potential impact on their child(ren)’s behaviour, development and wellbeing. For recovery, a child requires high levels of emotional literacy and intensive emotional labour from their non-offending parent(s) (Pretorius and colleagues, 2011). It is therefore imperative that any plan created around a child at risk of, or whom has been a victim of CSA, includes supporting the non-offending carer(s).

This insight aims to provide a thematic overview of the existing studies that explore the experiences of NOCs in the immediate aftermath of discovery and identifies the support needs of carers, concluding with some resources for social workers in working with families impacted by child sexual abuse. It is not able to cover all nuances and complexities practitioners face when working with families impacted by child sexual abuse in the longer-term, but signposts the reader to further resources at the end of this document.

The writer of this Insight is a doctoral student undertaking social work research with non-offending carers and has third sector practice experience working with children and families impacted by child sexual abuse and exploitation.

Legislative context

The refreshed National Practice Model (2022) requires any child’s plan to consider the family unit as holistically as possible, taking into account the needs of those around the child to inform delivery of support from various agencies. The National Principles of Holistic Whole Family Support (2022) further enshrines this approach to practice and encourages a non-stigmatising, collaborative approach to engaging with families in need. Ensuring that parents and carers are included and involved in decision-making is a key theme in the existing literature pertaining to responding well to families impacted by CSA. The 10 principles referenced in the Holistic Whole Family Support routemap (2022) include commitments to whole family, needs-based support that accounts for the family’s voice at every level of decision-making.

Supporting the non-offending carer – a summary of identified needs from the literature

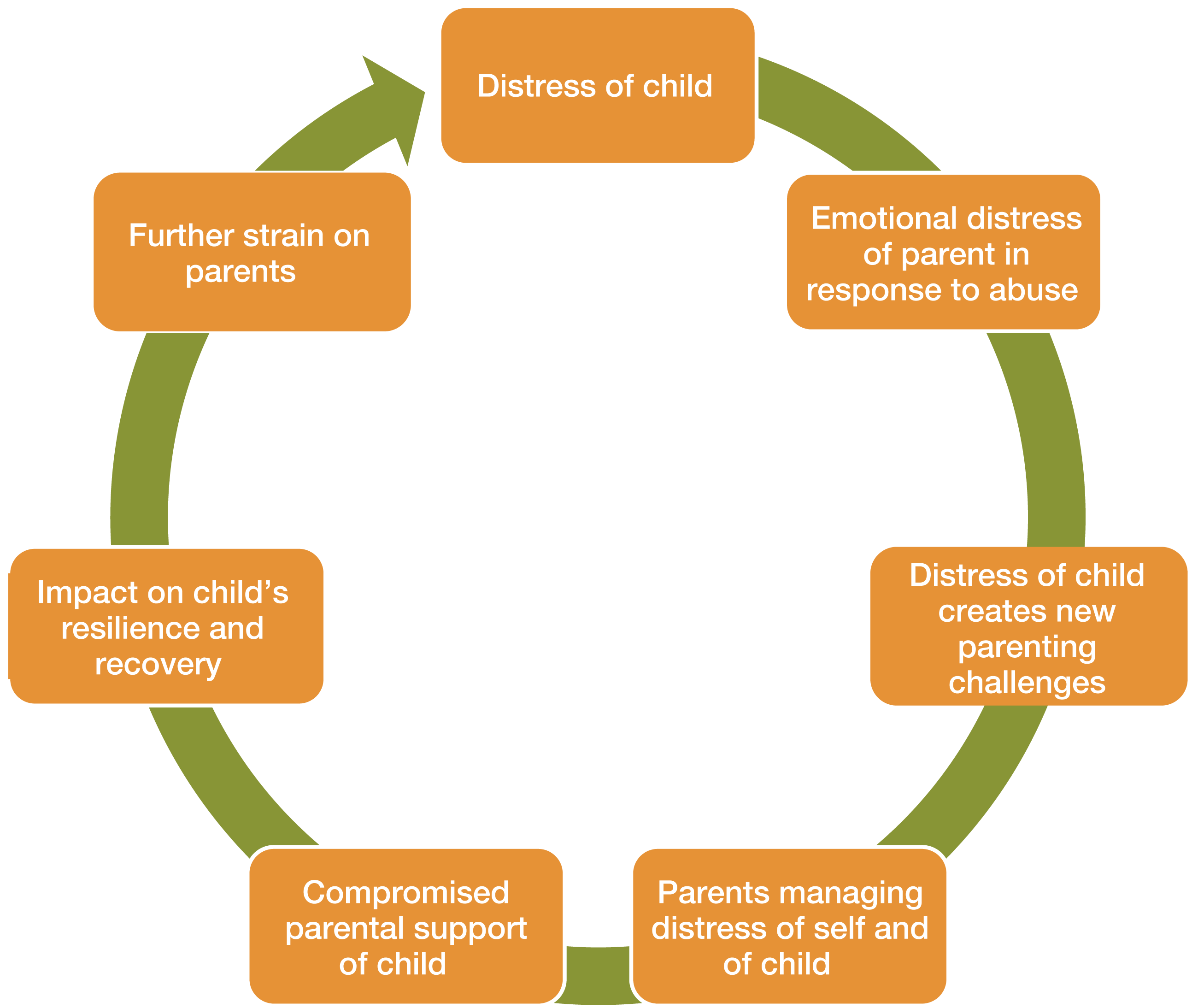

Parenting a child who has survived CSA can be incredibly challenging. The impact of learning of their child’s abuse is often traumatic and NOCs very often need their own psychological support following the abuse coming to light. Notwithstanding their own trauma and distress following discovery, NOCs have to navigate new systems (such as child protection procedures, police investigations etc) and challenging family dynamics (such as relationship breakdowns, relocations, issues with siblings) – all whilst caring for their child and protecting them from further harm. NOCs must also quickly learn how to help their child recover on a long term basis which requires knowledge on how to address potential problematic sexual behaviour, potential changes in living arrangements and feelings their child may experience of loss, self-blame and shame. Fisher and colleagues (2017) demonstrate the cyclical and interconnected nature of these challenges in Figure 1 below.

The challenges involved in parenting a distressed child following CSA

Due to the nuanced and challenging nature of recovery and the need for NOCs to adapt their parenting and balance their own emotional wellbeing, it is imperative that social workers seek to enhance their understanding of what NOCs experience. Building a trusting, supportive relationship with NOCs can aid in rebuilding confidence in parenting and forging relationships in a time where that trust and confidence is often jeopardised.

Distress and gender differences

Despite the paucity of research exploring the experience of NOCs, interview studies with NOCs both in the UK (see Scott and McNeish, 2018; Stitt, 2007; Wells, 2019) and internationally (see Daignault and colleagues, 2017; Deblinger and colleagues, 2010; Thompson, 2017; Spaulding, 2020; Sufredini and colleagues, 2020; Fuller, 2016) studies report similar findings relating to participants’ experiences of discovery of abuse and their subsequent interactions with child protection services. A significant commonality is the sense of intense distress and trauma felt about what their children have experienced, often compounded when the perpetrator is somebody known to or in the family (which is the most common form of CSA). NOCs report feeling grieved about what their child has suffered as well as conflicting feelings of loss and betrayal when the perpetrator is known to them (Elliot and Carnes, 2001; Kilroy and colleagues, 2014).

Whilst most studies focus on female carers, Daignault (2017) and her colleagues conducted interviews with female and male NOCs and found that whilst female carers reported the highest levels of distress in the immediate aftermath of disclosure, male carers reported their levels of distress increased over time. This increase over time was also found in Vladmir and Robertson’s (2020) study with non-offending fathers. Jenny Still (2016) highlights that fathers – particularly those who are not living in the family home – are often overlooked when creating family support plans and that their involvement and engagement in discussions around safety planning and whole family support should be sought by practitioners.

Participants of all genders reported feeling anger – at themselves, the perpetrator or the child – upon initial discovery as well as grappling with disbelief, disorientation and shock (Fuller, 2016; Philpott, 2008). These feelings often changed over time with men reporting more long-term feelings of anger and anxiety (Daignault and colleagues, 2017; Fuller, 2016; Vladmir and Robertson, 2020) and women reporting long-term depression and isolation (Scott and McNeish, 2018; Philpott, 2008; Wells, 2019). The existing literature offers little explanation for these gender differences and it would be premature to base recommendations on these findings without further investigation. However, these findings may increase awareness of potentially differing parental responses as practitioners begin to engage with families.

Isolation and loss

Following the CSA disclosure and subsequent investigations NOCs reported significant isolation and loss both emotionally and physically as a result of the abuse. Most NOCs describe taking significant measures to provide safety and healing for their child(ren) post-disclosure. These measures (which can include physical relocation, rebuilding the family unit, disassociation with the offender and those who may not believe the child, changing or leaving employment where necessary) often result in increased levels of isolation for NOCs and their children (Deblinger and colleagues, 2010; Thompson, 2017; Fuller, 2016; Philpott, 2008). Decrease in trust or complete familial/community breakdown heightens the sense of loss and isolation experienced by NOCs. This loss is heightened when the perpetrator of the abuse is a family member or partner and NOCs can experience grief at the breakdown of these relationships. This grief is described in the literature as disenfranchised grief as the sense of loss experienced by the NOC is often not validated or recognised as appropriate by those around them (Armitage and colleagues, 2023; Philpott, 2008). Familial isolation and relocation negatively impact the recovery of children who have experienced CSA due to increased levels of upheaval, change and feelings of self-blame (Fuller, 2016). However, Scott and McNeish (2018) argue that effective and knowledgeable social work practitioners can act as key agents to mitigate these adverse outcomes. A positive working relationship between a practitioner and a non-offending carer has been shown to improve outcomes for the affected child and overall family functioning (Forbes and colleagues, 2003; Hill, 2005; Hill, 2012; Scott and McNeish, 2018). However, many of the studies listed throughout this insight detail experiences with social work that compound feelings of distress and isolation for NOCs. Non-offending carers across several studies reported feeling blamed by social workers for the abuse against their child, judged as failing to protect their child, or feeling shame as a result of the perceived stigma of having social work involvement in their lives.

In 2007, Seán Stitt interviewed four organisations in the UK that supported non-offending mothers and several of the women using these services. Stitt found there to be a general lack of support across the country for women attempting to support their children after CSA as well as a lack of trust in statutory child protection services. This lack of trust was partially due to both service users’ and third sector workers’ beliefs that social workers attribute a large portion of blame toward non-offending mothers and do not offer meaningful support or intervention to assist the family (Stitt, 2007). These findings were similar to other studies that found mistrust between social workers and NOCs could be eased by adopting a more strengths-focussed, support based approach to practice. Studies found this mitigated against feelings of judgement and blame that hinder working relationships between NOCs and practitioners (see Glinkski, 2020; Hanisch and Moulding, 2011: Pike and colleagues, 2019; Plummer and Eastin, 2007).

Working with NOCs

The literature surrounding social work and NOCs is sparse, especially within a UK context, but the necessity of social work involvement in cases of CSA is clear. Social workers should seek to work alongside NOCs with the mutual goal of protecting the child from further harm and supporting their recovery. This presents many challenges, as practitioners must balance assessing parental protectiveness and supporting parents to build their confidence, resilience and existing strengths (Still, 2016; McGillvery and colleagues, 2017).

One of the most important goals for social workers in the immediate aftermath of CSA investigations is ensuring the physical safety of the child and reducing the risk of re-victimisation. As such, current risk should be assessed and appropriate safeguarding measures put into place to reduce the likelihood of further harm to the child (Still, 2016). In my own preliminary research findings, NOCs have stressed that this main priority is one that is shared and that they desire clear, concise direction for social workers around how to achieve this. A transparent, well-communicated safety plan requires a comprehensive assessment that ensures all parts of the child’s routine, and relationships are considered. As such, a large part of ensuring the safety of the child is assessing the protective capacity of the non-offending carer (Rigby and Callan, 2011; Still, 2016). In Scotland, Rigby and Callan (2011) developed the Non Offending Carer Risk Assessment (NOCRA) that aids social workers in assessing the protectiveness of NOCs after CSA over 10 in-depth sessions. The Lucy Faithfull Foundation (2023) have also developed a risk assessment for practitioners. However, the awareness and subsequent uptake of these assessment tools within general social work practice is low and there is little other guidance given to social workers as to ascertaining levels of protectiveness in a consistent, evidence-based manner (Plummer and Eastin, 2007). In her guide to professionals working with NOCs, Parkinson (2022, p33) summarises the key elements of working supportively alongside parents in the immediate aftermath of discovery whilst assessing parental capacity to safeguard the child from any further victimisation:

‘Key elements in an effective approach to working with parents therefore include:

- Including and involving parents

- Being non-judgmental

- Being sensitive to parents’ trauma

- Using respectful language

- Providing continuity

- Showing compassion and humanity

- Recognising parents’ strengths

- Being direct and open’

Practitioners may also wish to consider referring or signposting carers to organisations or services that can support them in their own recovery and rebuilding of their mental health. This aspect can be overlooked by NOCs as they seek to do everything to support their child without acknowledging the impact the abuse has had on them. Organisations like We Stand and Parents Against Child Exploitation can provide NOCs with essential counselling services that give them the opportunity to work through their own trauma and responses.

Belief and working with denial

Parental belief, both immediately post-disclosure and in the long term, is widely recognised as an integral factor in positive outcomes for children (Forbes and colleagues 2003; Knott and Fabre, 2014; Philpott, 2008; Scott and McNeish, 2018). Understanding the complexities of belief in their child for non-offending carers is a key part of a practitioner’s role in supporting families in the aftermath of CSA. It is necessary for practitioners to work alongside carers to cultivate and develop this belief in order to best support the child and move the family toward healing. Education is a key tool in this process as the literature demonstrates that the more informed carers are about the behaviours of offenders and the impact CSA has on children, the more likely they are to believe and continue to believe their child about the abuse (Mearnes and Thorne, 2013). The word ‘believe’ itself is a transitional verb; meaning that it is an active concept that is fluid and requires action to be fully realised. Understanding belief or believing as active processes as opposed to a singular event or conversation may assist social workers in partnering with carers to work towards fully believing and supporting their child.

Often, in cases where the perpetrator is biologically related to the NOC or in an intimate relationship with them, the NOC may find it difficult to believe or come to terms with the abuse their child has experienced. This denial is a common initial reaction to any traumatic or upsetting discovery, which should be taken into consideration when assessing parental capacity, especially in the immediate aftermath of discovery (Thompson, 2017; Parkinson, 2021). To anticipate that non-offending carers would immediately believe their children in these circumstances is arguably unrealistic and such an assumption may cause disconnect and/or conflict between the practitioner and the parent from the offset.

Sufredini (2020) and Thompson (2017) found that most parents have no idea that the abuse is taking place and that despite initial disbelief; NOCs would still put in place appropriate safeguarding measures for their children and uphold them. Only in very rare cases would parents choose to completely disregard safeguarding measures. Most of the studies that discussed denial in relation to NOCs found that carers would still seek to protect the child despite any reservations they may have and that the denial of abuse was often short-lived. (see Thompson, 2017, McGillivray and colleagues, 2017; Sufredini, 2020). However, practitioners should be aware that when a child is aware of continuing parental disbelief, they are more likely to retract any disclosure made in favour of preserving the relationship (Stolow and Snyder, 2011).

Working with denial is undoubtedly challenging for practitioners who are rightly concerned about further risk to the child. However, supporting NOCs to process discovery, whilst maintaining safeguarding measures, is more likely to result in service users trusting social workers in the long term and feeling empowered to make decisions around protecting their families (Still, 2016; Rigby and Callan, 2012). A practitioner should be able to demonstrate high levels of emotional literacy and practice continuous reflexivity when working with families affected by CSA. This must be supported by effective supervision from senior management as well as engagement with external mental health services when necessary. The impact of secondary traumatisation (sometimes referred to as vicarious trauma) for practitioners working with those who have been affected by sexual violence is well documented (see Jackson and colleagues, 2013; Gill and Weinberg, 2015). It is imperative that social workers are not isolated and are encouraged to access external resources and supports whilst also being empowered to develop internal systems needed to work with impacted families.

‘Parents as partners’

Scott and McNeish (2018) coined the term ‘parents as partners’ within their review of English statutory service provision for families affected by CSA. They found social work intervention with NOCs was more likely to be successful with the adoption of a strengths-based approach, with this supporting the parent’s relationship with their child, engagement with services and improving the family’s resilience in the longer term. This also provides for a more empowering and anti-oppressive practice model approach, rather than deficit focused and paternalistic models of care. The necessity of a partnership-based approach to practice was explicitly recommended in existing literature (see Daignault and colleagues, 2017; Forbes and colleagues, 2003; Gibney and Jones, 2014; Hill, 2005; Hill, 2012; Still, 2016; Parkinson, 2022). This approach is also consistent with the National Principles of Holistic Whole Family Support (2022).

To allow any service user to be a mutual partner involves a sharing of knowledge. In the context of working with NOCs, this involves social workers intentionally sharing their expertise in child sexual abuse with the non-offending carer. The importance of education and of educating carers is a theme recurrent in most of the literature. NOCs in a number of the identified studies reported that the lack of information sharing by practitioners during their engagement with services made them feel disempowered, stigmatised and ignorant to their child’s ongoing needs. This compounded existing feelings of helplessness and naivety brought to the fore from the abuse of their child. These studies recommend practitioners include an educational element in any support plan designed to support families. This should cover the behavioural patterns of child sex offenders, grooming awareness, the signs of child sexual abuse taking place as well as the emotional and behavioural impact the discovery of abuse and the abuse itself can have on children and their families (Daignault and colleagues, 2017; Fuller, 2016; Scott and McNeish, 2018; Thompson, 2017; Tolledo and Seymour, 2008).

Inclusion of education as part of a support plan enhances parental resilience as well as equipping them with the knowledge and skills needed to provide the appropriate care for their child, ultimately resulting in outcomes that are more positive for the child. Parents and carers who have received some form of education or have felt included in knowledge sharing with their respective practitioners within these studies all reported feeling less self-blame, reduced feelings of depression and isolation and increased confidence in their parenting skills (see Daignault and colleagues, 2017; Fuller, 2016; Hill, 2012; McGillivray, 2017; Philpot, 2008; Scott and McNeish, 2018; Thompson, 2017). Practitioners should also consider carers to be experts in their own children and family dynamics and that this knowledge is invaluable in creating a plan for the family going forward. Engaging with ‘parents as partners’ then, should also include recognising where social workers may learn from NOCs and ensuring that their voices, experiences and opinions are valued.

Implications for social work

Supporting and safeguarding families devastated by CSA is one of the most challenging roles undertaken by practitioners in any field of work. It can be intimidating to broach and the fear of saying or doing the wrong thing looms large. Ultimately, social workers need to ensure the safety of the child and assess the NOC’s ability to do this – but the way an investigation and subsequent plan is implemented can drastically impact upon the family’s ability to rebuild and move beyond the abuse. The first step for practitioners then must be to build upon their own knowledge with respect to preventing and responding to CSA and developing emotional literacy and reflexive skills. This will allow practitioners to work empathetically and effectively with non-offending carers to preserve and improve upon their own mental health as well as protecting their child from further harm and move beyond the abuse as a family.

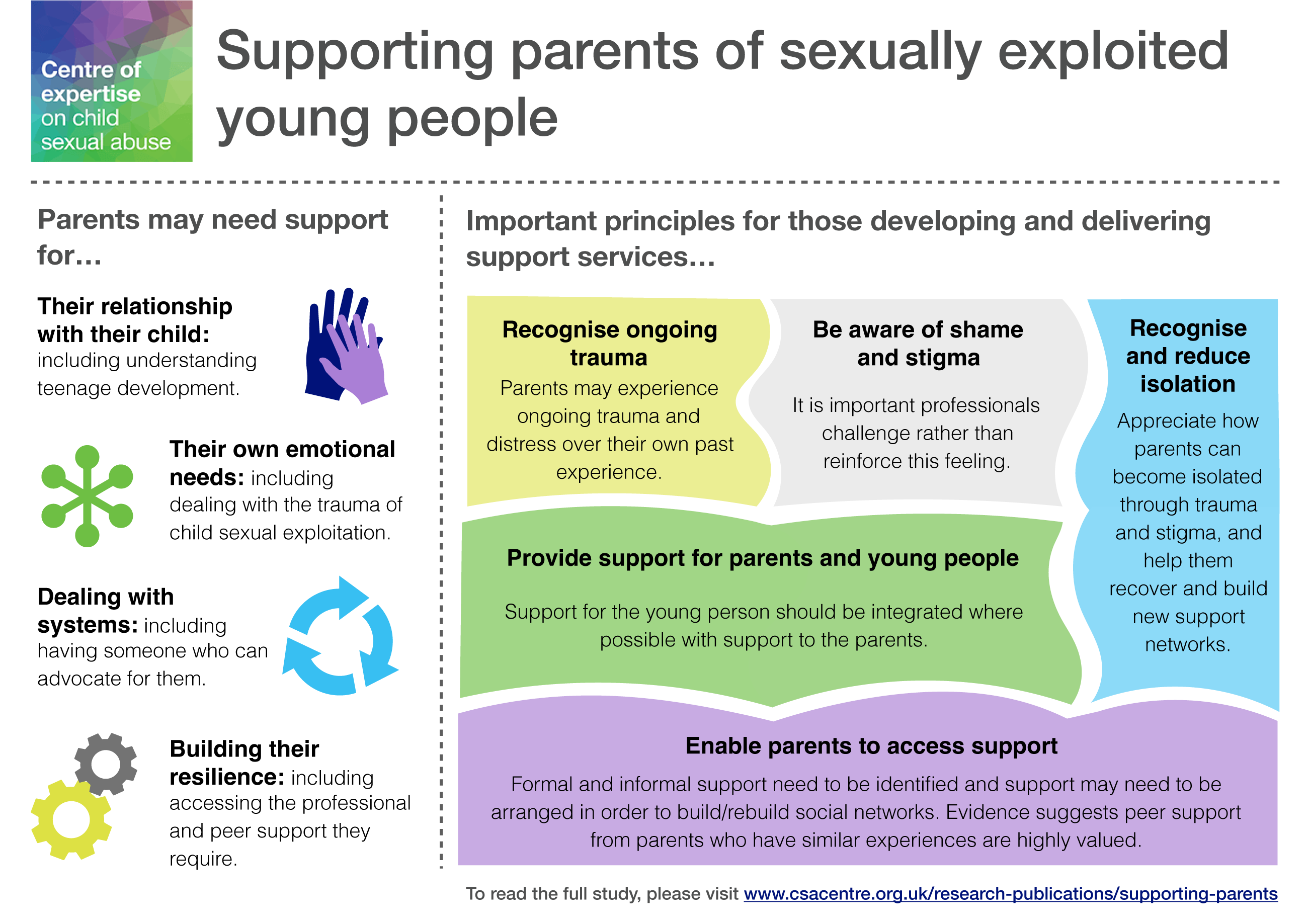

Figure 2 (over) is a useful graphic from the Centre of expertise on child sexual abuse (CSA Centre) that gives an overview of the main support needs for NOCs as well as important principles for practitioners.

This Insight intends to give practitioners an overview of the immediate support needs of non-offending carers after a disclosure of child sexual abuse by introducing recurrent themes in the literature and suggesting areas for development in practice. It is not possible to cover comprehensively all of the nuances and complexities practitioners face when working with families impacted by child sexual abuse. For a more comprehensive guide(s) specifically aimed at developing social worker skill, please engage with the listed resources.

Resources for practitioners

Centre of Expertise on Child Sexual Abuse

The team at the CSA Centre are a multi-disciplinary team who working alongside researchers, policy makers and practitioners to ensure an evidence-informed approach is applied to better understanding and responding to child sexual abuse at both an operational and strategic level. They do not offer frontline services but are a useful resource for enhancing practitioner development. The following resources are particularly useful:

- Practitioner guide (2022)

- Free e-learning course

- Managing risk and trauma after online sexual offending: a whole family safeguarding guide (2023)

The following three organisations also offer training and development opportunities for practitioners working with children and parents impacted by CSA as well as providing specialist support for service users in the form of support groups, advocacy, counselling and free helplines.

Stop it Now!

Stop it Now! Is part of the Lucy Faithfull Foundation and offers a confidential, anonymous helpline to anyone concerned about child sexual abuse including those worried about their own thoughts or behaviour; those worried about the sexual behaviour of another adult, child or young person; or adults concerned about child sexual abuse including survivors and professionals.

Helpline number: 0808 1000 900

Monday to Thursday: 9:00am – 9:00pm

Friday: 9:00am – 5:00pm

We Stand (formally known as MOSAC)

We Stand helps all non-abusing parents and carers whose children have been sexually abused and provides a range of support services and information for parents, carers and professionals dealing with child sex abuse. For more information see westand.org.uk or contact the free, confidential helpline.

Helpline number: 0800 980 1958

Monday, Thursday, Friday: 10:00am – 2:00pm

Tuesday and Wednesday: 10:00am – 6:00pm

Parents Against Child Exploitation (Pace UK)

‘Pace is a national charity working to keep children safe from exploitation by supporting their parents, disrupting the offenders and working in partnership with police and family services.’ [excerpt from PACE website]

Pace also train professionals and have a vast library of resources that can be accessed for free on their website.

References

- Azzopardi C (2022) Gendered Attributions of Blame and Failure to Protect in Child Welfare Responses to Sexual Abuse: A Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis. Violence Against Women, 28(6–7), 1631–1658

- Daignault I, Cyr M and Hébert M (2017) Working with Non-Offending Parents in Cases of Child Sexual Abuse. In L Dixon, DF Perkins, C Hamilton-Giachritsis and LA Craig (eds) The Wiley Handbook of What Works in Child Maltreatment

- Deblinger E et al (2010) Caregivers’ efforts to educate children about sexual abuse: A replication study. Child Maltreatment. 15, 91-100

- Elliott A and Carnes C (2001) Reactions of nonoffending parents to the sexual abuse of their child: A review of the literature. Child Maltreatment, 6, 4

- Fisher C et al (2017) The impacts of child sexual abuse: A rapid evidence assessment. London, UK: Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse.

- Forbes F, Duffy JC, Mok J et al (2003) Early intervention service for non-abusing parents of victims of child sexual abuse: Pilot study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 183, 66-72

- Fuller G (2016) Non-offending parents as secondary victims of child sexual assault. Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice no. 500. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology

- Gil S and Weinberg M (2015) Secondary trauma among social workers treating trauma clients: The role of coping strategies and internal resources. International Social Work, 58(4), 551–561

- Glinski (2020) "But they must have known!" Effectively working with non-abusing parents. London, UK: The Centre of expertise on child sexual abuse

- Hanisch D and Moulding N (2011) Power, Gender, and Social Work Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. Affilia. 26(3), pp.278-290

- Hernandez A, Ruble C, Rockmore L et al (2009) An Integrated Approach to Treating Non-Offending Parents Affected by Sexual Abuse. Social Work in Mental Health 7, 533-555

- Hill A (2012) Help for children after child sexual abuse: Using a qualitative approach to design and test therapeutic interventions that may include non-offending parents. Qualitative Social Work. 11, 4, 362-378

- Hill S (2005) Partners for protection: a future direction for child protection. Child Abuse Review. 14, 5, 347-364

- Jackson S, Backett-Milburn K and Newall E (2013) 'Researching distressing topics: emotional reflexivity and emotional labor in the secondary analysis of children and young people’s narratives of abuse', SAGE Open. 3, 2, 1-12

- Kilroy SJ et al (2014) “Systemic Trauma”: The impact on parents whose children have experienced sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 23, 481–503

- Knott T and Fabre A (2014) Maternal Response to the Disclosure of Child Sexual Abuse: Systematic Review and Critical Analysis of the Literature, Issues in Child Abuse Accusations vol. 20

- Lucy Faithfull Foundation (2023) About | How We Tackle Child Sexual Abuse

- McGillivray C et al (2018) Resilience in Non-Offending Mothers of Children Who Have Reported Experiencing Sexual Abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 27:7, 793-810

- Parents Against Child Exploitation (2023) Training for Practitioners

- Parkinson D (2022) Supporting Parents and Carers: A guide for those working with families affected by child sexual abuse. CSA Centre: Centre of Expertise on Child Sexual Abuse

- Philpott T (2008) Understanding child abuse: the partners of child sex offenders tell their stories. London: Routledge

- Pike N, Langham M and Lloyd S (2019) Parents’ experience of Children’s Social Care System when a child is sexually exploited. Leeds, UK: PACE

- Plummer C and Eastin J (2007) System intervention problems in child sexual abuse investigations: The mothers’ perspectives. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22, 775–787

- Pretorious G, Chauke A P and Morgan B (2011) The lived experiences of mothers whose children were sexually abused by their intimate male partners. Indo - Pacific Journal of Phenomenology 11, 1-14

- Rigby P and Callan T (2012) Non-Offending Carers Risk Assessment. Glasgow City Council

- Scott S and McNeish D (2018) Supporting parents of sexually exploited young people: An evidence review. London, UK: The Centre of expertise on child sexual abuse

- Scottish Government (2023) Routemap and National Principles of Holistic Whole Family Support: Improving outcomes for young people and children in Scotland

- Spaulding T (2020) Non-offending caregivers: The association of caring for sexually abused children, parental distress and self-efficacy, Carlos Albizu University

- Still J (2016) Assessment and intervention with mothers and partners following child sexual abuse: Empowering to protect. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

- Stitt S (2007) Non-offending Mothers of Sexually Abused Children: the Hidden Victims, The ITB Journal 8, 1

- Stolow K, Einhorn L and Snyder S (2011) Working with Non-offending Parents of Sexually abused Children. Dorothy B. Hersh Regional Child Protection Center. New Brunswick, NJ

- Sufredini F et al (2022) Narratives of Mothers Whose Children Had Been Sexually Abused: Maternal Reactions and Comprehension Regarding Child and Adolescent Sexual Abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 3, 3320-3345

- Thompson AJ (2017) The lived experience of non-offending mothers in cases of intrafamilial child sexual abuse: Towards a preliminary model of loss, trauma and recovery. Edith Cowan University Research Online

- Tolledo and Seymour (2013) Interventions for caregivers of children who disclose CSA: a review. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 772-781

- Vladimir M and Robertson D (2020) The Lived Experiences of Non-Offending Fathers with Children Who Survived Sexual Abuse, Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 29, 3, 312-332

- We Stand (2023) Mosac’s guide to impact issues for abused children

- Wells LJ (2019) The Secondary Survivors of Trauma: A Research Portfolio on the Experiences of Non-Offending Caregivers Whose Children Have Disclosed Sexual Abuse. University of Edinburgh, HLS Thesis Collection

About the author

Naomi McGookin is a final year PhD student at Glasgow Caledonian University where she is undertaking research alongside non-offending partners of online offenders in a participatory action research project. Prior to her doctoral studies, Naomi qualified in social work in 2018 and has ten years of experience working with survivors of sexual violence and their families. Naomi is particularly interested in using participatory methodologies and research methods that centre co-production to learn more about child protection in Scotland, the effects of child sexual abuse on the family, professional identity, the role of reflexivity and social work education. Naomi teaches regularly on the Social Work programmes at GCU with a focus on self-compassion, reflexivity, practitioner boundaries and recovery from secondary trauma.

Acknowledgements

This Insight was reviewed by Diana Parkinson (Centre of expertise on child sexual abuse), Ruth Stark (BASW), Nadia Wager (Teeside University) and Scottish Government colleagues from the Directorate for Children and Families.

Comments represent the views of reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of their organisations. Iriss would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time to reflect and provide feedback on this publication.

Credits

- Series Coordinator: Kerry Musselbrook

- Commissioning Editor: Kerry Musselbrook

- Copy Editor: Stuart Muirhead

- Designer: Ian Phillip