Summary

This summary focuses on evidence of the indirect impact on children from living with the effect of adult to adult coercive control. Overall there is very little research into coercive control without violence, and even less specific research into how children experience coercive controlling behaviours only, when living with domestic violence perpetrated by one caregiver to another. However, we have identified some key publications and sources of knowledge that seek to identify and explain the impact of coercive control on young people, where these effects are described specifically. Children who witness severe and ongoing parental conflict can have significant negative outcomes for children. Children who witness severe and ongoing parental conflict can display: externalising problems (such as behavioural difficulties, antisocial behaviour, conduct disorder); Internalising problems (such as low self-esteem, depression and anxiety); academic problems; physical health problems; and social and interpersonal relationship problems. It is important for people working in social services to understand the impact of coercive control and develop relevant assessment skills. This Outline provides contextual information and recommendations for reading and development.

Introduction

This evidence summary seeks to address the following questions relating to coercive and controlling behaviours:

- What is the impact on children of living in a household where adults evidence coercive and controlling behaviours?

- What are the effective methods of intervention for the child?

The summary focuses on evidence of the indirect impact on children from living with the effects of interparental/adult to adult coercive control.

About the evidence presented below

We drew on a wide range of evidence, including academic research in the fields of social work, healthcare, psychology and child protection in relevant databases (e.g. ASSIA, ProQuest Public Health, SCIE Social Care Online, Social Services Abstracts) health and social care guidelines (e.g. NICE, Campbell Collaboration and NHS) and recommendations from specialist organisations (e.g. NSPCC, CAFCASS, CELCIS, CRFR, Child Protection Scotland).

We searched using relevant key terms and variations of specific terminology to retrieve relevant results, including domestic abuse and domestic violence, child abuse, child adjustment problems, child behaviour problems, child witnesses, coercive control, emotional abuse, family violence, interparental conflict, intimate partner violence, marital aggression, and neglect.

Overall there is very little research into coercive control without violence (Crossman et al. 2016), and even less specific research into how children experience coercive controlling behaviours only, when living with domestic violence perpetrated by one caregiver to another (usually their father/father-figure against their mother). To illustrate, Callaghan et al. (2015) state:

[T]here is limited research that engages either with children’s lived experience of violence, or more specifically with their experience of psychological abuse and coercive control in family relationships affected by domestic violence.

The majority of research on children and domestic violence tends to focus on children’s exposure to physical violence (Katz 2016), and in the majority of cases emotional abuse co-occurs with physical abuse. Additionally, very few studies of the impact of domestic violence on children control for the effect of co-occurring child abuse (Wolfe et al. 2003), so in many cases it is not possible to identify the effects of a specific form of domestic violence, for example to measure the impact of coercive control specifically. Where studies do not differentiate between emotional and physical abuse, we have not been able to include these studies as they do not isolate the effect of witnessing and experiencing non-physical violence/abuse.

Where research has been conducted into the impact of coercive and controlling behaviour, the methods for analysing and understanding instances and examples of experiences are often not classified using a theoretical framework (for example Johnson's (2008) framework of intimate partner violence). This means that there is no standard approach to operationalising or measuring coercive control, which limits comparisons and generalisability across studies (Hardesty et al. 2015). This means it can be challenging for practitioners to use evidence to inform their assessments.

However, we have identified some key publications and sources of knowledge that seek to identify and explain the impact of coercive control on young people, where these effects are described specifically. This is in response to the specific information need relating to this Outline.

In terms of research into the effectiveness of interventions to support young people around witnessing or experiencing coercion and control, Howarth et al. (2015) suggest that many studies are limited by their conceptualisation of outcomes as narrow health-focused changes in children's symptoms and disorders. A focus on outcomes as broader concepts would enable the more effective capture of positive outcomes of interventions, but this would require a consensus on wellbeing outcomes that does not currently exist (Davies 2014). Where we have provided resources relating to effective interventions, much of the evidence is limited in this way.

Accessing resources

We have provided links to the materials referenced in the summary. Some of these materials are published in academic journals and are only available with a subscription through the The Knowledge Network with a NHSScotland OpenAthens username. The Knowledge Network offers accounts to everyone who helps provide health and social care in Scotland in conjunction with the NHS and Scottish Local Authorities, including many in the third and independent sectors. You can register here.

Background

Domestic violence and abuse

In 2016-17 there were 58,810 incidents of domestic abuse recorded by the police in Scotland. A higher proportion of women than men experienced partner abuse, at 3.4% and 2.4% respectively (Scottish Government 2017). Recognising children’s experiences of domestic abuse is an important concern in working effectively with them as victims and survivors (Callaghan 2015).

A UK study from 2013 suggests about 29.5% of children less than 18 have been exposed to domestic violence during their lifetime and approximately 5.7% of children and young people will experience domestic violence in a year (Radford et al. 2013). There are no clear figures for the extent of coercive control either with or without physical violence.

In the Scottish context, the Equally Safe national strategy focuses on gender based violence against women and girls which includes physical, sexual and psychological violence occurring in the family which is informed by the UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women (1993). The Declaration states:

Gender based violence is a function of gender inequality, and an abuse of male power and privilege. It takes the form of actions that result in physical, sexual and psychological harm or suffering to women and children, or affront to their human dignity, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life. It is men who predominantly carry out such violence, and women who are predominantly the victims of such violence. By referring to violence as "gender based" this definition highlights the need to understand violence within the context of women's and girl's subordinate status in society. Such violence cannot be understood, therefore, in isolation from the norms, social structure and gender roles within the community, which greatly influence women's vulnerability to violence.

Informed by this approach to conceptualising domestic abuse, in Scotland, the term is used to acknowledge that abuse is ongoing and encompasses physical and emotional violence (Scottish Government 2000):

Domestic abuse (as gender-based abuse), can be perpetrated by partners or ex partners and can include physical abuse (assault and physical attack involving a range of behaviour), sexual abuse (acts which degrade and humiliate women and are perpetrated against their will, including rape) and mental and emotional abuse (such as threats, verbal abuse, racial abuse, withholding money and other types of controlling behaviour such as isolation from family or friends).

A reflection of the Scottish Government’s approach to domestic abuse is the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Bill (2017), which recognises domestic abuse as a specific offence and seeks to “criminalise the complex coercive and controlling behaviour that for many victims is their experience of domestic abuse” (Scottish Government 2016).

Research evidence suggests that the psychosocial impact on young people of witnessing domestic violence and abuse can be severe:

- Higher risk of mental health difficulties throughout their lives

- Increased risk of physical health difficulties

- Risk of educational drop out and other educational challenges

- Risk of involvement in criminal behavior

- Interpersonal difficulties in their own future intimate relationships and friendships

- More likely to be bullied and to engage in bullying themselves

- More vulnerable to sexual abuse and sexual exploitation and to becoming involved in violent relationships themselves

- Lasting neurological impacts that can have far reaching implications for children’s lifelong well-being

(Callaghan et al. 2015)

Research indicates that children witnessing domestic violence is at least as impactful as being directly physically abused (Moylan et al., 2010; Sousa et al., 2011), and the NSPCC considers witnessing domestic abuse to be child abuse in itself. They state that long term effects of abuse and neglect include:

- Emotional difficulties such as anger, anxiety, sadness or low self-esteem

- Mental health problems such as depression, eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), self harm, suicidal thoughts

- Problems with drugs or alcohol

- Disturbing thoughts, emotions and memories that cause distress or confusion

- Poor physical health such as obesity, aches and pains

- Struggling with parenting or relationships

- Worrying that their abuser is still a threat to themselves or others

- Learning difficulties, lower educational attainment, difficulties in communicating

- Behavioural problems including anti-social behaviour, and criminal behaviour (NSPCC 2018)

However, due to the complex nature of the problem, there is a lack of clarity about what forms of violence and abuse lead to what specific negative outcomes. Fowler and Chanmugam’s (2007) critical review of five quantitative meta- and mega-analyses on the effects of childhood exposure to domestic violence concludes that there are many methodological flaws in the body of literature and areas with inconclusive results, as a result of design flaws, issues around definitions, and the heterogeneity and complexity of the population. Problems of defining psychological and emotional abuse have posed particular challenges (Allen 2013; Hamberger et al. 2017). These limitations within research that has been conducted so far mean that although there is wide consensus that childhood exposure to domestic violence is associated with negative emotional and behavioural outcomes, it is not possible to clearly identify the specific mechanisms through which exposure influences outcomes.

The impact on young people of witnessing non-physical domestic abuse such as coercive control is even less clear. One complicating issue is that it is not only the severity or frequency of abuse that influences impact (and the complexity of measuring these when coercive control does not occur in isolated incidents at individual times) but it is also related to children’s perceptions of conflict and the degree to which it is seen as threatening (Jouriles and McDonald 2014).

The Early Intervention Foundation (2018) reports that children who witness severe and ongoing parental conflict can have significant negative outcomes for children:

When the conflict between parents is frequent, intense and poorly resolved, it puts children’s mental health and long-term outcomes at risk. Children of all ages can be affected by destructive interparental conflict, from infancy to adulthood, but they may be affected in different ways. Children as young as six months show symptoms of distress when exposed to interparental conflict, infants up to the age of five display symptoms such as crying or acting out, and children in middle childhood (six to 12 years) and adolescents show emotional and behavioural distress. Children who witness or are aware of the conflict between parents, or who blame themselves, are affected to a greater extent.

Children who witness severe and ongoing parental conflict can display:

- Externalising problems (such as behavioural difficulties, antisocial behavior, conduct disorder)

- Internalising problems (such as low self-esteem, depression and anxiety)

- Academic problems

- Physical health problems

- Social and interpersonal relationship problems

In the long term, the above poor child outcomes are associated with: mental health difficulties, poorer academic outcomes, negative peer relationships, substance misuse, poor future relationship chances, low employability, and heightened interpersonal violence. The impact of interparental conflict on children can, therefore, be varied and long-lasting, as well as the risk that relationship behaviours and problems are repeated across the generations, as evidence suggests these children can go on to experience destructive conflict in their own future relationships. (EIF 2017)

Humphreys and Horton (2008) highlight the potential inadequacy of the division between direct child abuse and witnessing domestic abuse, and emphasise the importance of understanding witnessing and experiencing domestic abuse as being part of a holistic issue in which children may be more involved than observing from a distance:

[T]here are problems which arise from drawing ‘false’ distinctions between exposure to or witnessing domestic abuse and direct abuse, rather than responding holistically to the child’s experience (Edleson et al., 2003; Mullender et al., 2002). Research is now showing that children are involved in a myriad of ways when they live with domestic abuse. For instance, they may be used as hostages (Ganley and Schechter, 1996); they may be in their mother’s arms when an assault occurs (Mullender et al., 2002); they may be involved in defending their mothers (Edleson et al., 2003). Stanley and Goddard (1993) and Kotch (2006) also refer to violence within the community of people surrounding the family which may also instil fear and may contribute directly to the abuse of the child and the impact on well-being. Irwin et al., (2006) point out that describing this range of violent experiences as ‘witnessing’ fails to capture the extent to which children may become embroiled in domestic abuse.

Coercive and controlling behaviour

Domestic violence and abuse is:

Any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive or threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are or have been intimate partners or family members regardless of gender or sexual orientation. This can encompass, but is not limited to, the following types of psychological, physical, sexual, financial and emotional abuse.

Controlling behaviour is: a range of acts designed to make a person subordinate and/or dependent by isolating them from sources of support, exploiting their resources and capacities for personal gain, depriving them of the means needed for independence, resistance and escape and regulating their everyday behaviour.

Coercive behaviour is: an act or a pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim. (Home Office 2015)

A non-exhaustive list of coercive and controlling behaviours from the Home Office (2015) includes:

- Isolating a person from their friends and family;

- Depriving them of their basic needs;

- Monitoring their time;

- Monitoring a person via online communication tools or using spyware;

- Taking control over aspects of their everyday life, such as where they can go, who they can see, what to wear and when they can sleep;

- Depriving them of access to support services, such as specialist support or medical services;

- Repeatedly putting them down such as telling them they are worthless;

- Enforcing rules and activity which humiliate, degrade or dehumanise the victim;

- Forcing the victim to take part in criminal activity such as shoplifting, neglect or abuse of children to encourage self-blame and prevent disclosure to authorities;

- Financial abuse including control of finances, such as only allowing a person a punitive allowance;

- Threats to hurt or kill;

- Threats to a child;

- Threats to reveal or publish private information (e.g. threatening to ‘out’ someone).

- Assault;

- Criminal damage (such as destruction of household goods);

- Rape;

- Preventing a person from having access to transport or from working.

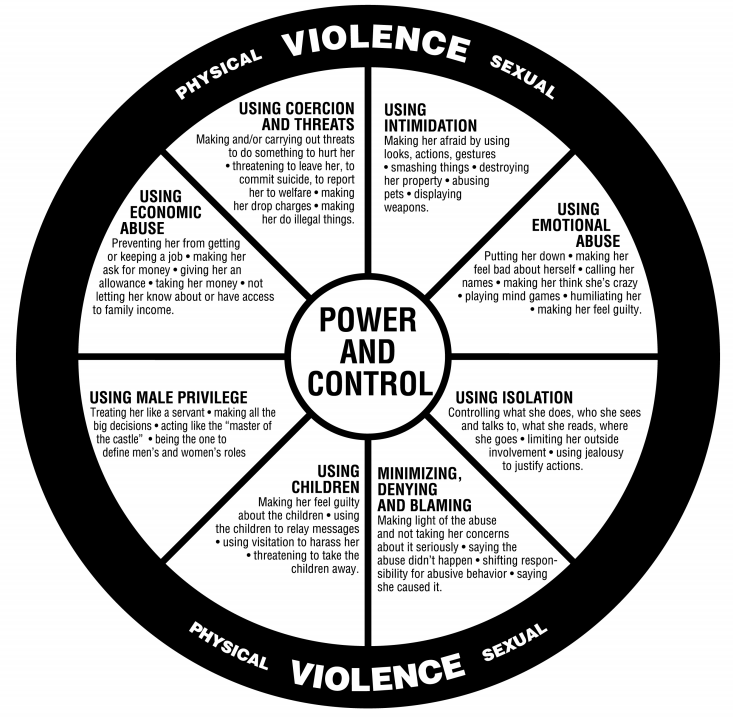

The diagram below was produced by the Duluth domestic abuse intervention program to illustrate the various manifestations of power and control in domestic abuse:

Jeffries (2016) discusses how non-physical coercive and controlling domestic violence, which she argues is common, can have extremely negative impact on victims:

In reality many perpetrators never use physical violence. Some may use what is best described as minor assaultive violence such as pushing, grabbing and/or getting “up in a victim’s face”. Others may threaten physical violence. Some may follow through on these threats, but only when they are losing control over the victim. The largest predictors of intimate partner homicide, for example, are, in fact, emotionally abusive and controlling behaviours and victim-instigated relationship separation (Stark 2007, pp. 276–77). Universally, victims of domestic violence report that it is the non-physical elements of abuse that causes them the most pain and trauma both in the short and long-term.

Citing Hart’s (2011) analysis of family court judgements in Australia, and other research, Jeffries (2016) discusses how there may be a lack of adequate consideration of domestic violence, and coercive control in particular, when making judgements on family cases. She describes the difference between framings of ‘parental conflict’ and the realities of coercive control:

Coercive control was frequently reconstituted as mutual parental “conflict”, and it was this, rather than exposure to what was often extreme acts of domestic violence by fathers against mothers, which impacted adversely on the children. While it is the case that children from high-conflict families can experience adverse effects, their experiences and needs are different from those living within environments characterised by coercive control. High conflict relationships are characterised by mutual distrust and disagreement. This is fundamentally different from contexts where a perpetrator’s intent is to wield power and control over their victim/s via numerous tactics aimed to intimidate and incite fear (Hart 2011, p.37; Meier 2003, p.191; Stark 2009, pp. 294–95).

Research conducted on judicial decision-making in family law matters (Hart and Bagshaw 2008) argues that perpetrator/child relationships can be maintained by invalidating consideration of the perpetration of coercive control through “discourses grounded in normative misconceptions of gender and domestic violence” (Jeffries et al. 2016).

In response to the evidence needs from the Outline request, this review focuses on the impact of non-physically violent coercive and controlling behaviour between adults in a household and the impact it may have on young people within the household, rather than the behaviour of an adult towards a child aged under 16.

In the context of the impact on young people, coercive and controlling behaviour can include intimate partner violence (IPV) that involves use of the victimized partner’s children or the children in their care, and their role as a parent or carer. Some of the tactics that are referenced in the literature on IPV overlap with child maltreatment.

Where IPV involves children, examples of tactics or behaviour include:

[M]aking threats to kidnap, harm, or kill the children; making threats to report the mother to Child Protective Services (CPS) and have the children removed from her care; making threats to leave the children without a mother by deporting or killing her; criticizing, degrading, and humiliating the mother either directly to her when her children are present or as comments to her children when she is not present; requiring the children to keep track of their mother’s activities, relay threatening messages, or harass her; physically abusing, kidnapping, or otherwise putting the children in danger as a means to intimidate, threaten, or punish the mother; limiting or withholding resources so the mother can not meet her children’s needs; expressing jealousy of the mother’s attention toward her children; preventing the mother from comforting and caring for her children; forcing the children to participate in abuse of their mother; and abusing the mother in front of her children or while she is pregnant, thereby undermining her value as a person, her role as a mother, and her ability to protect her children. (Ahlfs-Dunn and Huth-Bocks 2016)

The context of abuse, and of coercive control, is often not understood by practitioners, which Watson (2017) suggests can result in inappropriate demands being placed on women by social workers. Katz (2016) identifies the following as key messages for practitioners:

- Children experiencing domestic violence may be affected by more than the physical violence perpetrated by one parent against the other

- Children may be harmed by non-physical abusive behaviours inherent to coercive control-based domestic violence, including continual monitoring, isolation and verbal/emotional/psychological and financial abuses

- Responsibility for the impacts on children of coercive control-based domestic violence should be placed with the perpetrator (usually fathers/father-figures) and not with the victimised parent (usually mothers)

Evidence

As discussed above, it is important for people working in social services to understand the impact of coercive control and develop relevant assessment skills (Pitman 2017). The resources provided below provide a background to the research around children’s experiences of coercive control and the negative impacts this can have.

Impact on children of witnessing coercion and control at home

Artz, S et al. (2014) A comprehensive review of the literature on the impact of exposure to intimate partner violence for children and youth. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 5(4), pp.493–587 (Open Access)

This comprehensive review on the literature around the impact of witnessing domestic violence on children explores the extent of negative outcomes, including neurological disorders, physical health outcomes, mental health challenges, conduct and behavioural problems, delinquency, crime, and victimization, and academic and employment outcomes. The authors conclude that the individual categories of impacts are closely related and interconnected. They report that the research reviewed shows that children who are exposed to intimate partner violence are at significant risk for lifelong negative outcomes.

Boudreault-Bouchard, A-M et al. (2013) Impact of parental emotional support and coercive control on adolescents' self-esteem and psychological distress: results of a four-year longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence, 36, pp.695-704 (Available with NHSScotland OpenAthens username or author repository copy)

This questionnaire-based study of 605 adolescents in Canada aimed to investigate the impact of parental emotional support and coercive control on adolescents’ self-esteem and psychological distress between the ages of 14 and 18. The authors conclude that adolescents need parents who are supportive, without being intrusive or coercive, to develop individuality and autonomy.

Callaghan J, et al. (2015) Beyond "witnessing": children’s experiences of coercive control in domestic violence and abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence (Available with NHS Scotland OpenAthens username or author repository copy)

This article focuses on children’s lived experiences of domestic violence and

coercive control, and considers whether understanding them as direct victims

might have implications for support services, including social care,

mental health support, and legal protection. Using data from 20 semi-structured individual interviews conducted in the United Kingdom with children aged 8 to 18 years, the study used spatial emotional mapping of the children’s houses and family drawings to support and facilitate children’s accounts of their lived experiences.

The children had experienced both physical violence and patterns of control and abuse in their homes. Reported impacts include the internalisation of violence and abusive control, producing a sense of depression and self-loathing, which in one instance is connected by the participant to their self-harm. Other impacts include as sense of constant fear, embarrassment, shame, disruption and distress. The authors emphasise the impact of witnessing coercive control on children:

“They are immediately involved and affected by coercive and controlling behavior that does not simply target the adult victim but affects the entire family.”

Cedar Network (2018) Impact of domestic abuse on children (website)

The Cedar Network website draws on research to outline the impact of experiencing domestic abuse on children. It identifies three categories - physical; social and emotional; and behavioural:

- Physical: eczema; bed-wetting; nightmares and sleep disturbances; excessive screaming as babies

- Social and emotional: fear; anxiety; guilt; sense of responsibility for siblings, non-abusive parent, and pets; sadness; low self-esteem; depression; difficulty concentrating at school; social isolation; difficulty making and keeping friends.

- Behavioural:

- Internalising: introversion, withdrawal

- Externalising: aggression or ‘acting out’

Ibrahim, J et al. (2018) Childhood maltreatment and its link to borderline personality disorder features in children: a systematic review approach. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 23(1), pp.57–76 (Available with NHS Scotland OpenAthens username)

This systematic review of research into the association between maltreatment and borderline features in childhood. 10 studies making an association of any type of maltreatment (physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal abuse, emotional abuse and neglect) with borderline features in children or children diagnosed with a BPD (12 years or below) are included. Childhood maltreatment is identified as a risk factor for borderline features in childhood. However, the authors state that longitudinal research is required to establish the link between childhood borderline features and adult borderline features.

Although the studies included in the review used a variety of different methods to assess either borderline personality features or BPD and used a range of subscales, including affective instability, interpersonal dysfunction/disturbed relatedness/negative relationships, identity problems, self-harm/suicidal ideation, inappropriate anger, emptiness/boredom, paranoid ideation/psychosis, abandonment and impulsivity, all the studies used a subscale of affective instability and a measure of negative relationships and the authors concluded that all the included studies were considering the same symptoms: affective instability and difficulties in interpersonal functioning.

All 10 studies showed a significant association between BPD/borderline features and childhood maltreatment, with all forms of abuse and neglect being significantly associated with BPD/borderline features. A limitation of the review is that the majority of studies use different definitions and classifications of abuse/neglect, which makes it difficult to find specific associations between one type of abuse or neglect with borderline features. However, as the majority of people experiencing abuse or neglect experience multiple forms, isolation of effects would be extremely difficult to identify. The authors also identify limited research on the impact of different severities of abuse and neglect.

Katz, E (2016) Beyond the physical incident model: how children living with domestic violence are harmed by and resist regimes of coercive control. Child Abuse Review, 25(1), pp.46-59 (Available with NHSScotland Open Athens username or author repository copy)

This paper reports on the findings of 30 semi-structured interviews (15 with mothers and 15 with children; not all paired) using a thematic framework for questions to explore the range of attitudes and experiences of participants relating to domestic violence and coercive controlling behaviour.

The children in this study experienced a range of coercive controlling behaviours which the author links to negative outcomes:

Fathers/father-figures controlled mothers’ time and movements, isolated mothers (and consequently isolated children) from sources of support and produced family environments that narrowed mothers’ and children’s space for action. These behaviours entrapped children (and their mothers) in constrained situations where children’s access to resilience building and developmentally-helpful persons and activities was limited. The impacts of perpetrators/fathers preventing children from spending time with their mother, visiting grandparents or going to other children’s houses may contribute to emotional and behavioural problems in children as much as, or even more than, physical violence perpetrated against their mother.

Children described feeling “sad, annoyed and angry” by coercive and controlling behaviours exhibited by abusive parents. Non-abusive parents linked coercive controlling behaviours from partners as delaying children’s speech development, restricted children’s social lives, and limited children’s opportunities to build relationships with non-abusive people outside their immediate family.

A limitation of the research is that the connections made to the behavioural problems observed in the children in the study, such as withdrawn or aggressive behaviours, are inferred rather than proven. Additionally, many of the participants had experienced multiple types of abuse (as is the situation in the majority of domestic violence cases), so it is not possible to identify clear relationships between forms of abuse and impacts.

Naughton, CM et al. (2017) Exposure to domestic violence and abuse: evidence of distinct physical and psychological dimensions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, epub ahead of print (Available with NHSScotland Open Athens username or author repository copy)

This study explores whether two separate dimensions, physical and psychological domestic violence and abuse (DVA), were evident in adult children's reports of their exposure to DVA in their family of origin, and whether these dimensions affected psychological well-being and perceived satisfaction with emotional support.

Police and Crime Commissioner for Surrey (2016) Understanding Coercive Control with Professor Evan Stark (YouTube video)

Professor Evan Stark gives a lecture to help improve understanding of coercive control, a new offence in the United Kingdom.

Rhoades, KA (2008) Children’s responses to interparental conflict: A meta-analysis of their associations with child adjustment. Child Development, 79(6) pp.1942-1956 (author manuscript)

This study is a meta-analysis of the relations between children’s adjustment and children’s cognitive, affective, behavioural, and physiological responses to interparental conflict (IPC). Although interparental conflict differs in some ways to coercive control, literature around interparental conflict may provide an insight into the negative impacts of children witnessing coercive control in an abusive situation between caregivers.

This review focuses on the impact of children’s responses to IPC on child adjustment and finds that children’s cognitive, affective, behavioural, and physiological responses to IPC are moderately related to child adjustment.

Sousa, C et al. (2011) Longitudinal study on the effects of child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence, parent-child attachments, and antisocial behavior in adolescence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26, pp.111-136 (Available with NHSScotland Open Athens username or author manuscript)

This study examined the unique and combined effects of child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence on later attachment to parents and antisocial behaviour during adolescence. Analyses also investigated whether the interaction of exposure and low attachment predicted youth outcomes. Findings suggest that, although youth dually exposed to abuse and domestic violence were less attached to parents in adolescence than those who were not exposed, for those who were abused only and those who were exposed only to domestic violence, the relationship between exposure types and youth outcomes did not differ by level of attachment to parents. However, stronger bonds of attachment to parents in adolescence did appear to predict a lower risk of antisocial behaviour independent of exposure status. Preventing child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence could lessen the risk of antisocial behaviour during adolescence, as could strengthening parent—child attachments in adolescence. However, strengthening attachments between parents and children after exposure may not be sufficient to counter the negative impact of earlier violence trauma in children.

Swanston, J et al. (2014) Towards a richer understanding of school-age children’s experiences of domestic violence: the voices of children and their mothers. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19(1), pp.184-201 (Available with NHSScotland Open Athens username and author repository copy)

This study sought to capture the perspectives of school-aged children and their mothers, to develop a richer understanding of children’s experiences of domestic violence, using a community-based sample of five children and three mothers. Key findings include that all of the children spoke about their awareness of many different forms of domestic violence taking place within their home, with a sense of it becoming more frequent, pervasive and severe as time went on, and that their experiences are in line with research suggesting that exposure to domestic violence is not a linear experience and is associated with multiple forms of abuse.

Vu, N et al. (2016) Children's exposure to intimate partner violence: a meta-analysis of longitudinal associations with child adjustment problems. Clinical Psychology Review, 46(1), pp.25-33 (Available with NHSScotland Open Athens username)

This meta-analysis reviewed 74 studies that examined longitudinal associations between children's exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV) and their adjustment problems. Results indicated that children's exposure to IPV is linked prospectively with child externalizing, internalizing, and total adjustment problems. The authors found that the magnitude of the association between IPV exposure and child externalizing and internalizing problems strengthens over time.

Welsh Women’s Aid (2017) Professor Evan Stark: Coercive Control and Children (YouTube video)

In this video, Professor Evan Stark, forensic social worker and author of Coercive Control talks to Welsh Women’s Aid about how he’s discovered controlling behaviour affects children and young people.

Recommendations around intervention

Wilson (2017) identifies training and guidance as important to social workers’ development in supporting women and children experiencing coercive control:

Social workers should develop an understanding of coercive control and explore the misconceptions surrounding domestic abuse. Social workers may need training and guidance in order to develop appropriate responses to women (Wiesz and Wiersma, 2011). Liegghio and Caragata (2016) recommend training and education in a safe environment where social workers can have the opportunity to reflect on prejudices and assumptions so that micro-aggression can be made visible.

In addition to the resources recommended by Wilson in Iriss Outline 36 (Safe Lives assessment tools and the Scottish Government’s My World Triangle), the following resources may be informative.

Australian Government (2015) Children’s exposure to domestic and family violence: key issues and responses (pdf)

This report suggests that therapeutic responses to children exposed to domestic and family violence should include working with mothers (or the non-offending parent) and children to strengthen attachment and should be trauma-informed.

CAFCASS (2017) Practice pathway: a structured approach to risk assessment in domestic abuse (pdf)

This practice pathway has been formulated to provide the practitioner with a structured, focussed and stepped framework for assessing cases where domestic abuse is a feature. The pathway is not a change of direction but a tool to assist the analysis of risk and child impact when presented with conflicting accounts or a complex family situation. It highlights the need to be succinct and clear when assessing high risk situations where there are presenting or alleged lethal behaviours and lower risk cases which may conclude with safe evidence based recommendations. The guide is compatible with a ‘menu of options’ approach to intervention using the threshold tool – the Barnardos DV RIM and the DAPP referral and reporting templates.

Early Intervention Foundation (2018) EIF Commissioner Guide: reducing the impact of interparental conflict on children (pdf)

The Early Intervention Foundation produced a practical planning tool to support local commissioners and leaders of services for children and families to reduce the impact of conflict between parents on children. This guide includes information on:

- How interparental conflict impacts on children

- Why interparental conflict affects some children more than others

- What sorts of services seek to address the impact of interparental conflict on children

- The national and local context for work on interparental conflict

- Which organisations have specialist knowledge about interparental conflict

- The implications of interparental conflict for local family services

- Approaches to evaluation

- How to measure interparental conflict and its impact at a family level

- How to measure the impact of interparental conflict and understand local need

- What data to use to understand local needs

- How to reduce the impact of interparental conflict on children locally

- What interventions can reduce interparental conflict and improve child outcomes

- How to match interventions with local contexts

- How to persuade my stakeholders to engage on interparental relationships

- Case studies of good practice

Early Intervention Foundation (2018) Reducing parental conflict hub (website)

The Reducing Parental Conflict Hub is an online repository for local leaders, commissioners and key stakeholders to find key EIF evidence, information on the case for action, and guidance on what works to reduce parental conflict.

Fong, VC et al. (2017) A systematic review of risk and protective factors for externalizing problems in children exposed to intimate partner violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, February 2017 (author repository copy)

This systematic review investigates the outcomes of exposure to IPV for children, considering both physical and psychological abuse. The findings of this systematic review suggest that interventions provided to families exposed to intimate partner violence need to target both maternal and child risk factors in order to successfully reduce child externalizing problems:

Findings indicate that mothers with education and training in positive parenting strategies (e.g., praise, spending time with her child) and the consistent use of calm, non-physical discipline (e.g., time out, removal of privileges) are likely to be helpful in promoting a warm parent-child relationship and reducing behaviour problems. Recognizing that mothers have also been victims of violence and providing treatment for mental health difficulties including anxiety, depression, and PTSD is also likely to be crucial for the success of family interventions aimed at reducing child externalizing problems. Treatment of maternal distress and improving mothers’ ability to set clear, consistent limits and engage with their child in a warm and sensitive manner is likely to be particularly important for reducing externalizing problems in children who have been exposed to IPV.

Harold, G et al. (2016) What works to enhance inter-parental relationships and improve outcomes for children. University of Sussex and Early Intervention Foundation for Department of Work and Pensions (pdf)

This evidence review explores research relating to the quality of the inter-parental relationship, specifically how parents communicate and relate to each other, and children’s long-term mental health and life chances. The research indicates that parents/couples who engage in frequent, intense, and poorly resolved interparental conflicts put children’s mental health and long-term life chances at risk.

The field in the UK is in the early stages of development with many gaps in knowledge about how to engage families effectively, how to replicate quality of intervention at scale, and how to evaluate and monitor impact on child outcomes. However, there is a growing international body of well-evidenced interventions which indicate positive impacts on both the couple relationship and child outcomes and some examples provided in this report may be useful for practitioners.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016) Domestic violence and abuse (pdf)

This quality standard covers domestic violence and abuse in adults and young people aged 16 years and over. It covers adults and young people who are experiencing (or have experienced) domestic violence or abuse, as well as adults and young people perpetrating domestic violence or abuse. It also covers children and young people under 16 years who are affected by domestic violence or abuse that is not directly perpetrated against them. This includes those taken into care.

Stanley, N et al (2015) Preventing domestic abuse for children and young people (PEACH): a mixed knowledge scoping review. Public Health Research, 3(7) (Open Access)

A range of interventions that aim to prevent domestic abuse has been developed for children and young people in the general population. While these have been widely implemented, few have been rigorously evaluated. This study aimed to discover what was known about these interventions for children and what worked for whom in which settings.

Stanley, N and Humphreys, C (Eds) (2015) Domestic violence and protecting children: new thinking and approaches. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers (ebook available through NHS Libraries)

In this volume, the authors present an overview of the innovative work taking place in relation to domestic violence and child protection. This book looks at new prevention initiatives and how interventions for children exposed to domestic violence have been developed. It shows how services for abusive fathers have evolved and provides discussion and critique of a number of new initiatives in the field of interagency risk assessment. With international perspectives and examples drawn from social care, health care and voluntary sectors, this book brings together established ideas with recent thinking to provide an authoritative summary of current domestic violence and child protection practice.

References

- Ahlfs-Dunn, SM and Huth-Bocks, AC (2016) Intimate partner violence involving children and the parenting role: associations with maternal outcomes. Journal of Family Violence, 31(1), pp.387–399 (paywalled or author manuscript)

- Allen, M (2013) Social work and intimate partner violence. New York, Routledge (book)

- Callaghan, JEM et al. (2015) Beyond ‘witnessing’: children’s experiences of coercive control in domestic violence and abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, December (paywalled or author manuscript)

- Cedar Network (2018) what is coercive control? (website)

- Crossman, KA et al. (2016) “He could scare me without laying a hand on me”: mothers’ experiences of nonviolent coercive control during marriage and after separation. Violence Against Women, 22(4), pp.454-473 (paywalled)

- Davies, SC (2014) Annual report of the Chief Medical Officer: public mental health priorities: investing in evidence. London: Department of Health (pdf)

- Early Intervention Foundation (2018) EIF Commissioner Guide: reducing the impact of interparental conflict on children (pdf)

- Fowler, DN and Chanmugam, A (2007) A critical review of quantitative analyses of children exposed to domestic violence: lessons for practice and research. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 7(4), pp.322-344 (archived journal)

- Hamberger, LK et al. (2017). Coercive control in intimate partner violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 37(1), pp.1-11 (paywalled)

- Hardesty, J et al. (2015). Toward a standard approach to operationalizing coercive control and classifying violence types. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(4), pp.833–843 (paywalled or author manuscript)

- Hart, AS (2011) Child safety in Australian family law: responsibilities and challenges for social science experts in domestic violence cases. Australian Psychologist, 46(1), pp.31–40 (paywalled)

- Hart, AS and Bagshaw, D (2008) The idealised post-separation family in Australian family law: a dangerous paradigm in cases of domestic violence. Journal of Family Studies, 14(2-3), pp.291-309 (paywalled)

- Home Office (2015) Controlling or coercive behaviour in an intimate or family relationship: statutory guidance framework (pdf)

- Howarth, E et al. (2015) The effectiveness of targeted interventions for children exposed to domestic violence: measuring success in ways that matter to children, parents and professionals. Child Abuse Review, 24(4), pp.297–310 (Open Access)

- Humphreys, C and Horton, C (2008) Literature review: better outcomes for children and young people experiencing domestic abuse - directions for good practice. Chapter two: the research evidence on children and young people experiencing domestic abuse. Scottish Government (pdf)

- Johnson, MP (2008) A typology of domestic violence: Intimate terrorism, violence resistance, and situational couple violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press (book available through NHS Library)

- Moylan, CA et al. (2010). The effects of child abuse and exposure to domestic violence on adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior problems.

- Journal of Family Violence, 25(1), pp.53–63 (paywalled)

- NSPCC (2018) What is domestic abuse? (website)

- Pitman, L (2017) Living with coercive control: trapped within a complex web of double standards, double binds and boundary violations (Open Access)

- SafeLives (2014) SafeLives Dash risk checklist for the identification of high risk cases of domestic abuse, stalking and ‘honour’-based violence (pdf)

- Scottish Government (2017) Domestic abuse recorded by the police in Scotland, 2016-17 (pdf)

- Scottish Government (2015) Using the My World Triangle (and where appropriate, specialist assessments) to gather further information about the needs of the child or young person (website)

- Scottish Government (2000) National strategy to address domestic abuse in Scotland (pdf)

- Sousa, C et al. (2011) Longitudinal study on the effects of child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence, parent-child attachments, and antisocial behavior in adolescence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(1), 111–36 (paywalled or author manuscript)

- Stark, E. (2007). Coercive control: how men entrap women in personal life. New York: Oxford University Press (book vailable through NHS Libraries)

- United Nations (1993) Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women (website)

- Watson, D (2017) Domestic abuse and child protection: women’s experience of social work intervention. Iriss Insight 36 (website and pdf)

- Wolfe, DA et al. (2003) The effects of children’s exposure to domestic violence: a meta-analysis and critique. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6(3), pp.171-187 (paywalled)

- Zolotor, AJ et al. (2007) Intimate partner violence and child maltreatment: overlapping risk. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 7(4), pp.305-321 (archived journal)

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the NSPCC Information Service for support with evidence searching around domestic violence.