Key points

- Domestic abuse is rooted in gender inequality.

- Women are most often seen as primarily responsible for child safety, despite the perpetrators responsibility for harm and abuse.

- The social attitudes that fuel domestic abuse and attribute blame to women for men’s violence can also be present in social work practice.

- The context of abuse, and of coercive control, is often not understood by practitioners, resulting in inappropriate demands being placed on women by social workers.

- Women do not feel listened to and do not have their needs met appropriately by social workers.

- The threat of having children removed by social workers is acutely felt by women. Often this threat denies the efforts women have made to protect their child from abuse, and does not take into account the challenges and the increased risk of violence faced by women when leaving their abuser partner.

- A failure by social workers to recognise the context of women’s lives and respond appropriately can re-traumatise women who have already experienced abuse and trauma.

Introduction

This Insight examines how women’s narratives of their experience of domestic abuse and social work intervention in cases of child protection could inform practice in Scotland. While acknowledging that domestic abuse is experienced by both men and women, in all types of relationship, this review focuses on mothers experiencing abuse perpetrated by men. The literature suggests that women become more constrained and are under tighter surveillance in these cases. Practice assumptions by social workers can mirror the action of abusive male partners and the oppression of women in society. This review has drawn on both UK and international research. It evolved from the author’s final year dissertation for the social work degree course at the University of the West of Scotland.

Context for practice

The context for domestic violence in Scotland can be described as a society of systemic gender inequality. Inequality and gender stereotyping are reinforced through media, sports, education, pornography, legislation and religious teachings (McVey, 2015). Gender inequality is recognised as the significant context for domestic abuse:

Violence against women and girls can best be understood as a cause, and a consequence, of structural gender inequality. The framing of violence against women in terms of male privilege and power, and in terms of women’s economic inequality and lack of political representation is essential.

(Women’s Aid, 2014)

This understanding of violence against women as being closely linked to structural gender inequality has been adopted by the Scottish Government through policy initiatives such as Equally Safe: Scotland’s Strategy for Preventing and Eradicating Violence against Women and Girls report (Scottish Government, 2014a). Scottish Government guidance suggests that, contained within gender inequality and assumptions about women’s roles, are the tactics of control used by men to strip away women’s freedoms within abusive relationships (Scottish Government, 2015a).The attitudes fuelling domestic abuse appear to run deep in society. One in four women will experience domestic abuse in their lifetime (Scottish Government, 2014a), while research shows that 50% of women with a disability will experience domestic abuse across the UK as a whole (Mogowan, 2004, cited in Gill, Thiara and Mullander, 2011).

Between 2014 and 2015, the Scottish Children’s Reporter received referrals regarding 2,742 children nationwide, on grounds they had a close connection to a perpetrator of domestic abuse. This was the third most reported ground for referral, following ‘lack of parental care’ and ‘offence related’ referrals (Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration, 2015). Children’s social work statistics for Scotland show that 2,882 children were recorded on local authority child protection registers in July 2014. The most common concerns for these children raised at case conference were parental substance misuse, emotional abuse and domestic abuse (Scottish Government, 2014).

Domestic abuse and child protection

The best interests of the child is a central consideration in practice with children. This approach is reflected in Scottish Government child protection guidance, ‘where a child is thought to be at risk of significant harm, the primary concern will be for their safety’ (Scottish Government, 2014b, p15). Clearly the focus is on children. However, this position becomes problematic where parents are held to account for childcare in a society characterised by gender inequality. Literature suggests that within a child protection context, women are most often seen as primarily responsible for protecting children, despite their partner’s responsibility in perpetrating abuse (Humphreys and Absler, 2011).

Social workers appear to struggle to find a balance between ensuring child safety and empowering women, while meeting the legal frameworks and local procedures for child protection (Keeling and Wormer, 2012). Research suggests practitioners initially related to women as victims, however, as time progressed and abuse continued workers made increasing demands of women to ensure child safety (Jenney and colleagues, 2014). The construction of mothers as being primarily responsible for childcare sets women up for blame for the perpetrator’s abusive actions, and renders the abusive partner’s behaviour invisible to social services (Mandel, 2010).

There have been significant developments in Scottish policy, policing and legislation regarding domestic abuse. The Equally Safe national strategy prioritises early and effective intervention for preventing violence. Highlighting the important role that third sector organisation such as Scottish Women’s Aid, ASSIST and Rape Crisis Scotland play in developing and providing services for women, the strategy also highlights the importance of partnership working between third sector and statutory agencies, for example, through Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conferences, or MARACs (Scottish Government, 2014a). The development of a single national police force, Police Scotland, has brought with it the establishment of the National Rape Task Force and the Domestic Abuse Task Forces (Scottish Government, 2015a). The introduction of the Abusive Behaviour and Sexual Harm (Scotland) Act 2016 includes provision for a specific aggravator for abusive behaviour toward a partner or ex-partner.

As part of its legislative program for 2016-17, the Scottish Government plans to introduce the Domestic Abuse Bill. This bill aims to develop new legislation which ‘will ensure that psychological abuse, such as coercive and controlling behaviour, can be effectively prosecuted under the criminal law’ (Scottish Government, 2016, p11). The hope of many respondents to government consultation on criminal law reform is that the creation of a specific offence could help end a victim blaming culture (Scottish Government, 2015b).

The experience of domestic abuse

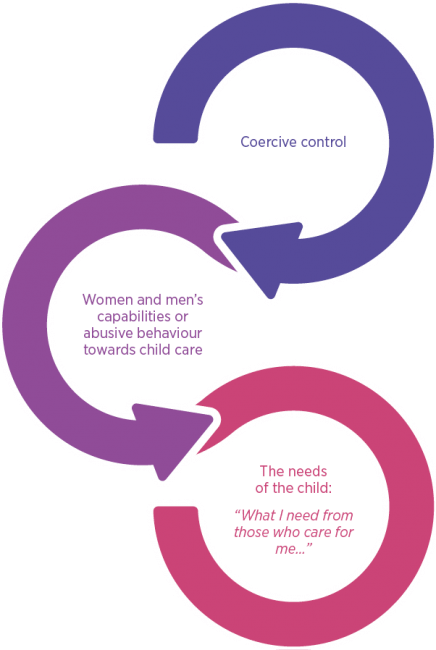

Coercive control

Domestic abuse is often described as a pattern of violence and coercive control. Coercive control is used as a strategy to gain the service of women and reinforce male dominance. Tactics of control most often target the default roles assigned to women as homemakers, sexual partners and mothers, in order to establish a regime of dominance over women (Stark, 2013).

This theory of control shifts attention away from characteristics of abuse as solely physical, and helps dispel the myth that women have sufficient autonomy to end abusive relationships between conspicuous episodes of violence. Wiesz and Wiersma (2011) found that nearly two thirds of respondents to their survey agreed that if mothers experienced domestic violence more than once and did not find a way to stop the violence, then this was neglectful to children. This denies the difficulties women experience in leaving their partners.

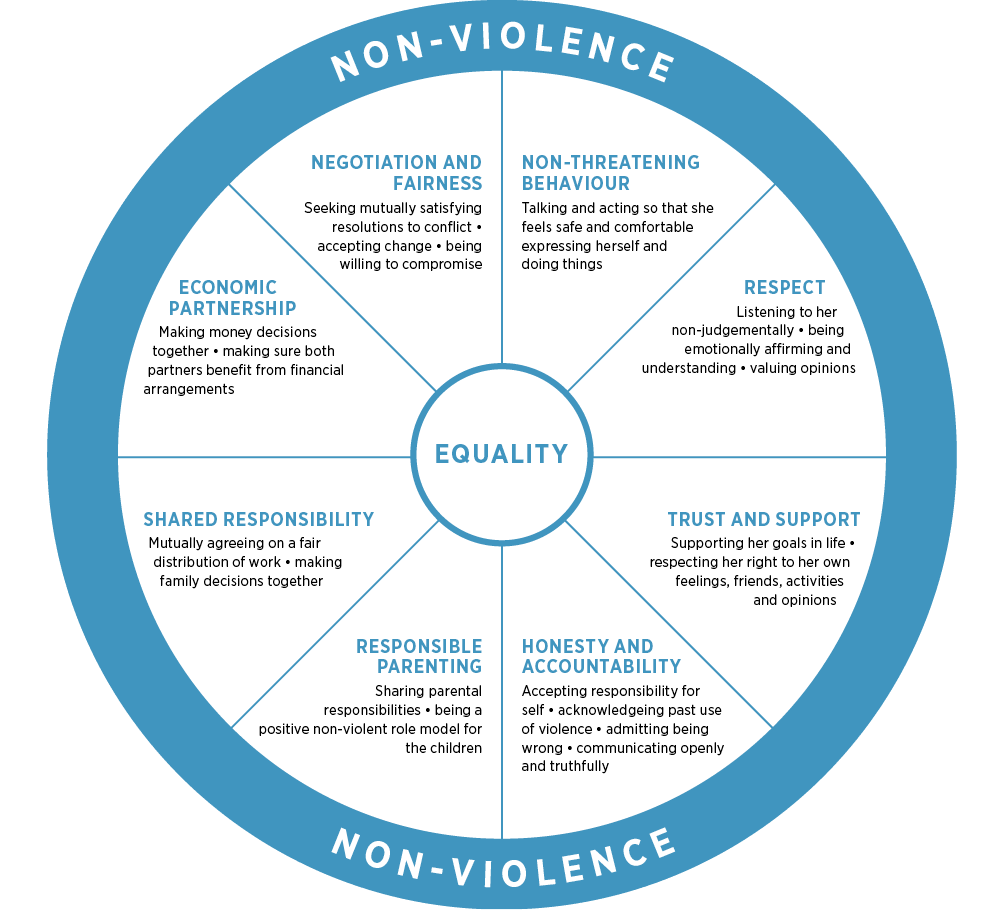

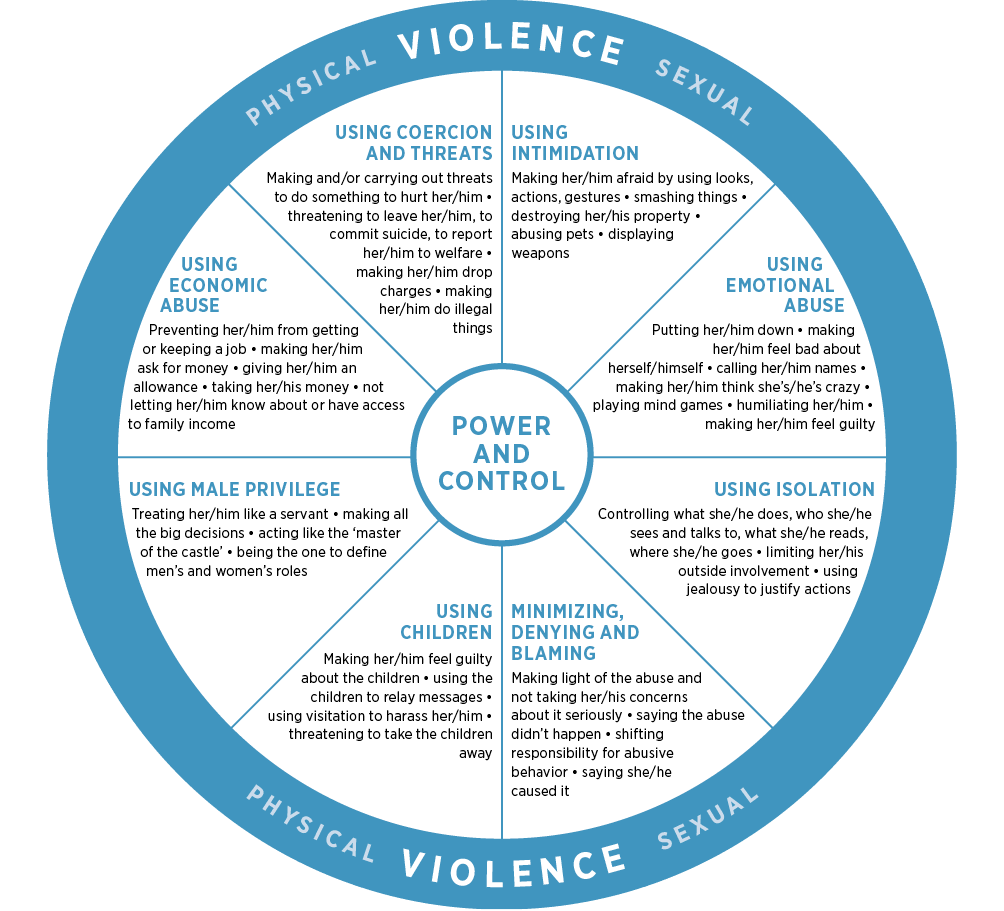

Coercive control comprises four main tactics: violence, intimidation, isolation and control. Control and isolation are used to limit resources and supports for women and to micro-manage women’s behaviour. Often involving the dictation of rules and behaviours that women must follow, coercive control can mean that women feel watched and controlled at all times, even when the perpetrator is not present (Stark, 2013). The women in Kelmendi’s (2015) study described physical and emotional violence, intimidation, threats against children and other family members, insults, isolation and name-calling. The Duluth model of power and control is a useful illustration of the characteristics of coercive control (Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs, 2011) [fig. 1 & 2 below].

The impact of abuse

Women often described how their experience of abuse impacted on their wellbeing and ability to live full lives. Many of the women in the research described mental health issues that developed as a result of the abuse they experienced, often resulting in depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts. Many women were afraid that their abusers would use knowledge of their mental health difficulties against them (Sullivan and Hagen, 2005). Women often discussed how the impact of abuse had led to engaging in substance misuse. These women often felt overwhelmed and depressed and felt unable to change their situations without support (Hughes, Chau and Poff, 2011). Despite women consistently aiming to put the care of their children first, women often felt they had lost control of their mothering due to the impact of abuse (Lapierre, 2010). However, practitioners should be cautious of viewing women only as helpless victims. Stark (2013) suggests that a reframing of social work intervention can develop a strength perspective that recognises and builds on the courage it takes to survive coercive control.

The process of leaving

Women’s narratives highlight competing issues compelling women either to stay or to leave abusive relationships. Many reported leaving their partners multiple times before making the final decision to end the relationship. Women stated that a desire to keep the family together, the best interests of their children; and a lack of social and financial support as reasons why they stayed in abusive relationships (Kelmendi, 2015). Themes of love and loss were also discussed in the literature. Messing, Mohr and Durfee (2015) examined women’s experiences of leaving through the adaptation of models of grief, where women experienced stages of denial, isolation, anger, indecision, depression and acceptance, as they went through the process of leaving.

Many women in the literature identified that leaving, and seeking support to leave, greatly increased the risk of harm from the perpetrator. Research has shown that 76% of women killed by their partner were killed in the first year following separation (Brennan, 2016). Asking women to leave their partner can increase the risk of violence. In the first few years post-separation, women faced three main barriers to recovery: post-separation violence; continued control through contact visits between children and abusive perpetrators; and the lack of safe, secure accommodation (Katz, 2015).

The experience of social work intervention

A small proportion of women in the literature found social work intervention helpful (for example, Ghaffar, Manby and Race’s, 2012) and several interlinking themes emerged to help inform practice. However, Hughes, Chau and Poff (2011) found that only three out of sixty-four women spoke positively about intervention, stating that social workers listened to them and provided appropriate supports.

Women’s needs

Women found social work to be unhelpful during intervention in a number of areas. Women found that the long-term impact of abuse, such as mental health and substance misuse difficulties, were not recognised by workers (Ghaffar, Manby and Race, 2012). Despite social work involvement, often women did not receive support for substance misuse (Hughes, Chau and Vokrri, 2015). Women who had a disability reported that social workers often focused on their disability and failed to recognise abusive behaviour, unless the women herself made a disclosure (Gill, Thiara, and Mullander, 2011). Researchers have also suggested that the complex nature of black and ethnic minority women’s experiences of racial, gendered and sexual oppression, is often not fully considered in policy or practice (Gill, 2013).

Blame

Women often felt blamed by social work, reporting that they had been told that it was them who had put children at risk by continuing to stay with an abusive partner (Keeling and Wormer, 2012). Women’s narratives reveal a complex relationship with blame. Some women felt that their own background of being in care was used against them during child protection considerations (Hughes, Chau and Poff, 2011). Many others found that the lack of social work intervention with abusive partners implicitly placed blame of harm to children on women themselves (Jenney and colleagues, 2014).

Threats

Women stated that social workers did not take the context of their abuse into account and were told that they must leave their partners or their children would be removed (Hughes Chau and Poff, 2011). In many cases, mothers became too angry or too paralysed with fear and emotion to move forward (Bundy-Fazioli, Brair-Lawson and Hadrian, 2009). Women demonstrated that the interventions they received fundamentally missed what they needed: recognition of their strengths in mothering, and time and support to help them make the changes required (Hughes, Chau and Vokrri, 2015).

Listening

Women appreciated workers who took time to understand the context of their lives and assessed the ‘real story’ (Jenney and colleagues, 2014). However, researchers also found that few women felt listened to or understood, and subsequently did not feel supported. (Hughes, Chau and Poff, 2011). Women also struggled with how much of the truth to provide, sometimes fearful of the consequences of intervention, and often presenting an appearance of cooperation, while not fully disclosing violence (Jenney and colleagues, 2014). This suggests several levels of discourse for women; personal narratives that acknowledge the ‘truth’ while constructing the self, the desired future self, and protecting themselves against violence.

Micro-aggressions

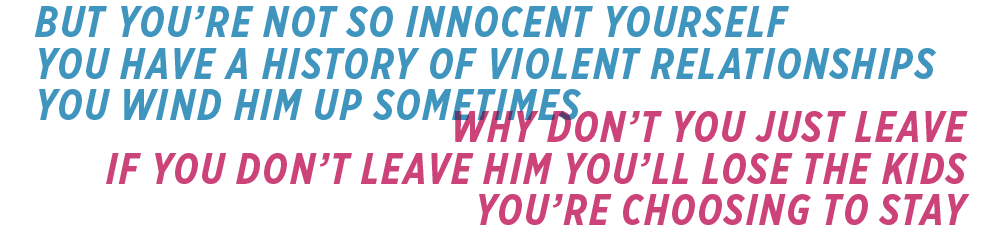

Responding to those who have experienced trauma with denial, minimisation or stigmatisation can compound the original experience of trauma. A failure to respond to women appropriately can lead to re-traumatisation. Micro-aggressions are subtle forms of verbal and non-verbal communication that intentionally or unintentionally reinforce structural disadvantage and oppression of marginalised individuals (Balsam and colleagues, 2011; cited in Liegghio and Caragata, 2016). Researchers have considered micro-aggression as an invisible form of interpersonal violence. Examples of micro-aggressions perpetrated by professionals include: minimising the issues affecting individuals, failing to consider the role of gender, reinforcing stereotypical roles, and making inappropriate recommendations that deny the realities of the service user. An understanding of this subtle action of values and language can help practitioners respond in a more helpful way [fig. 3].

Intersectionality

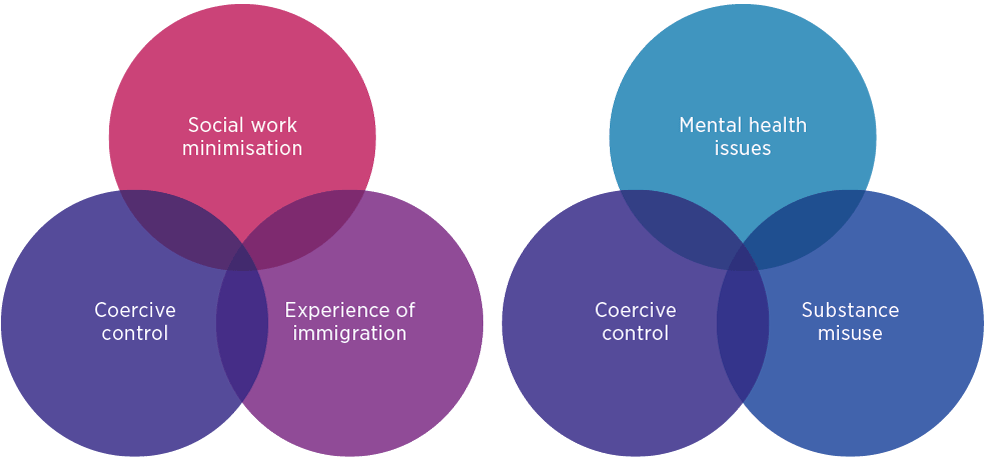

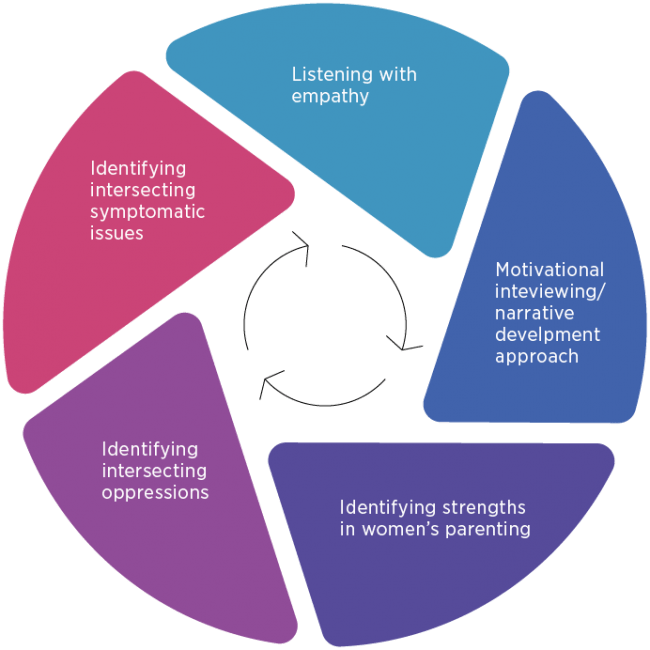

Nixon and Humphreys (2010) suggest that a reframing of domestic violence should draw on interlocking patterns of class, race, gender, disability and sexuality. They argue that by drawing on intersectional theory, workers can challenge violence against women while developing a culturally and historically sensitive understanding of individual women’s different experiences. Women’s narratives suggest that intersecting issues and oppressions relating to domestic abuse affect their stress and ability to cope with parenting (Hughes, Chau and Vokrri, 2015). Intersectionality is a useful tool to develop a fuller understanding of the situation faced by women and identify their needs [fig. 4 & 5].

Implications for practice

The research suggests that workers should listen to women, avoid threats and blame, focus on perpetrators behaviour, meet women’s needs and work to increase women’s capacity for safety, freedom and child care.

Avoid normative assumptions that reproduce the oppression of women

Social workers should develop an understanding of coercive control and explore the misconceptions surrounding domestic abuse. Social workers may need training and guidance in order to develop appropriate responses to women (Wiesz and Wiersma, 2011). Liegghio and Caragata (2016) recommend training and education in a safe environment where social workers can have the opportunity to reflect on prejudices and assumptions, so that micro-aggression can be made visible.

Develop a shared narrative with women

The research highlights the importance of listening to women and developing a clear picture of women’s own understanding of their situation. Holland and colleagues (2014) suggest promoting change through motivational interviewing; perhaps acknowledging that many women will be experiencing the process of change or loss and struggle with denial or ambivalence (Messing, Mohr and Durfee, 2015). When the assessment of women’s strengths in parenting are more inclusive, identifying and validate their efforts, better partnership working is ensured (Mandel, 2010).

Meeting women’s needs better protects women and children

The literature suggests a complex interplay of factors that make up women’s experiences. Practitioners should examine the intersecting oppressions and issues women experience, and work to address women’s needs, such as addictions and mental health issues, financial difficulties and the need for safety. As national guidance for child protection suggests, the most effective way to protect children is to support the non-abusing parent (Scottish Government, 2014b). Practitioners could consider a staged approach for engagement with women [fig. 6].

Avoid blame and focus on the perpetrator’s harmful behaviour

Mandel (2010) advocates using the framework of coercive control to inform assessment, by examining the perpetrator’s pattern of coercive control and the actions he has taken that have harmed women and children. By explicitly addressing perpetrators behaviour, workers may help women to address any sense of blame that has been placed upon them (Jenney and colleagues, 2014).

Assess the impact of coercive control on families and parenting

A framework for child assessment is well established in Scotland in the form of the GIRFEC National Practice Model (Scottish Government, 2016). A complementary framework, such as the Safer and Together model (Mandel, 2010) or the assessment tools developed by the Saver Lives charity (Safer Lives, 2016) might help to identify the impact of coercive control on women’s parenting. These approaches can inform existing child assessment frameworks, such as the My World Triangle, which assesses parents’ ability to meet the needs of the child (Scottish Government, 2016) [fig. 7].

Avoid threats and coercion

Practitioners should avoid making demands that deny the challenges faced by women and that could increase the risk of harm. While planning for intervention, workers should consider the risks that women might identify in terms of the consequences of any proposed action or intervention (Jenney and colleagues, 2014). Social workers may face many dilemmas while working in partnership with women and following statutory responsibilities to protect children. Mandel (2010) suggests that in most cases, risk posed to children by an abusive partner can be mitigated by intervention with the perpetrator and working in partnership with women. However, he suggests that in some cases the risk from the perpetrator remains so high that social work services must take action to protect the child. He also suggests that it may be difficult to collaborate with women if they deny, or do not recognise, the risk posed by the perpetrator towards the child.

Social workers have a role to play in helping women to recognise abuse. Once this recognition has taken place, work can begin to reconnect women to the resources, supports and opportunities needed to overcome coercive control (Stark, 2013).

Conclusion

The experiences of women highlight multiple layers of oppression and unmet need, difficult power-relationships and a general misunderstanding of the issues facing women experiencing domestic abuse. The literature suggests that practice that is sensitive to women’s needs and focuses on perpetrator behaviour can better protect women and children, and empower women to recognise abuse and work towards change. Women’s narratives of their experiences suggest that such an approach is possible with relatively small changes to the language and behaviour of social work services. However, a deeper more challenging shift may need to take place in training and awareness development, which might challenge the assumptions and beliefs of social workers.

References

- Brennan, D (2016) Femicide census, profiles of women killed by men: redefining an isolated incident

- Bundy-Fazioli, K, Brair-Lawson, K and Hardiman, E (2009) A qualitative examination of power between child welfare workers and parents, British Journal of Social Work, 39, 144–1474

- Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs (2011) Duluth Wheel Gallery

- Gill, A, Thiara, R and Mullander, A (2011) Disabled women, domestic violence and social care: the risk of isolation, vulnerability and neglect, British Journal of Social Work, 41,148–165

- Gill, A (2013) Intersecting inequalities: implications for addressing violence against black and minority ethnic women in the United Kingdom. In: Lombard, N and McMillan, L, Violence against women: current theory and practice in domestic abuse, sexual violence and exploitation, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

- Ghaffar, W, Manby, M and Race, T (2012) Exploring the experiences of parents and carers whose children have been subject to child protection plans, British Journal of Social Work, 42, 887–905

- Holland, S, Forrester, D, Williams et al (2014) Parenting and substance misuse: understanding accounts and realities in child protection contexts, British Journal of Social Work, 44, 1491–1507

- Hughes, J, Chau, S and Poff, D (2011) “They’re not my favourite people”: what mothers who have experienced intimate partner violence say about involvement in the child protection system, Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 1084–1039

- Hughes, J, Chau, S and Vokrri, L (2015) Mothers’ narratives of their involvement with child welfare services, Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work, 31, 3

- Humphreys, C and Absler, D (2011) History repeating: child protection responses to domestic violence, Child and Family Social Work, 16, 464–473

- Jenney, A et al (2014) Doing the right thing? (Re) Considering risk assessment and safety planning in child protection work with domestic violence cases, Children and Youth Services Review, 47, 92–101

- Katz, E (2015) Recovery-promoters: way in which children and mother support one another’s recoveries from domestic violence, British Journal of Social Work, 45, 1, 153–169

- Keeling, J and Wormer, K (2012) Social worker interventions in situations of domestic violence: what we can learn from survivors’ personal narratives, British Journal of Social Work, 42, 1354–1370

- Kelmendi, K (2015) Domestic violence against women in Kosovo: a qualitative study of women’s experiences, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30, 4, 680–702

- Lapierre, S (2010) More responsibilities less control: understanding the challenges and difficulties Involved in mothering in the context of domestic violence, British Journal of Social Work, 45(1), 153–169

- Liegghio, M and Caragata, L (2016) “Why are you talking to me like I’m stupid?”: the micro-aggressions committed within the social welfare system against lone mothers, Affilia: The Journal of Women and Social Work, 31, 1, 7–23

- Mandel, D (2010) Child welfare and domestic violence: tackling the themes and thorny questions that stand in the way of collaboration and improved child welfare practice, Violence Against Women, 16, 5, 530–536

- McVey, G (2015) Responding to violence against women

- Messing, J, Mohr, R and Durfee, A (2015) Intimate partner violence and women’s experience of grief, Child and Family Social Work, 20, 30–39

- Nixon, J and Humphreys, C (2010) Marshalling the evidence: using intersectionality in the domestic violence frame, Social Politics, 17, 2, 137–158

- Safe Lives (2016) Knowledge Hub

- Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration (2015) Online statistics 2014–15

- Scottish Government (2014) Children’s social work statistics Scotland, 2012–13

- Scottish Government (2014a) Equally Safe: Scotland’s strategy for preventing and eradicating violence against women and girls

- Scottish Government (2014b) National guidance for child protection in Scotland 2014

- Scottish Government (2015a) Equally Safe – reforming the criminal law to address domestic abuse and sexual offences. Scottish Government Consultation Paper

- Scottish Government (2015b) Reforming the criminal law to address domestic abuse and sexual offences: analysis of consultation responses

- Scottish Government (2016) A plan for Scotland: the government’s program for Scotland 2016–17

- Scottish Government (2016) National practice model

- Stark, E (2013) Coercive control. In: Lombard, N and McMillan, L (eds.), Violence against women: current theory and practice in domestic abuse, sexual violence and exploitation, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

- Scottish Parliament (2016) Abusive Behaviour and Sexual Harm (Scotland) Act 2016, Asp 22

- Sullivan, C and Hagan, L (2005) Survivors’ opinions about mandatory reporting of domestic violence and sexual assault by medical professionals, Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work, 20, 3, 346–361

- Weisz, A and Wiersma, R (2011) Does the public hold abused women responsible for protecting children?, Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work, 26, 4, 419–430

- Women’s Aid (2014) Scottish NGO briefing for UN special rapporteur on violence against women

Acknowledgements

The content of this Insight was reviewed by Lyndsey Byrne (East Lothian Health and Social Care Partnership, Children’s Service), Neil MacLeod (Scottish Social Services Council), Louise Moore (Women and Children First, Renfrewshire Council), Lesley O’Donnell, (NHS Education for Scotland), Marsha Scott (Scottish Women’s Aid) and colleagues from Scottish Government. Comments represent the views of reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of their organisations. Iriss would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time to reflect and comment on this publication.