Key points

- Workplaces and practice tasks offer rich sources of professional learning for social workers across their career

- Evidence from the lived experience of social workers shows how they learn through daily practice tasks undertaken in diverse workplace settings

- Learning in the workplace is a complex web of multiple interwoven physical and emotional elements for social workers

- Some social workers’ most significant learning experiences are down to chance

- Social workers need to learn with other social workers

- Understanding what learning in the workplace involves for social workers is important for strategic planning of continuous professional development and effective organisational practices to support this

Introduction

This Insight considers how social workers learn in, through and at work, which is drawn from recent Scottish empirical evidence from their lived experiences. Additional evidence is drawn together to help reconceptualise workplace learning for social workers, a unique group with diverse tasks and roles.

Professional learning is central to social work across career stages in which formal, informal and self-directed modes are promoted. Learning through practice is also a major integral element of qualifying programmes. Beyond the qualifying stage, workplace learning offers rich opportunities to learn. However, it is not fully recognised or valued by social workers or organisations that employ them.

In the workplace, the way that tasks can be designed to foster learning are not maximised. Organisational strategies invariably rely on tangible, topic-focused or direct/formal training activities to meet perceived needs. Ultimately, understanding the complexity of what learning in the workplace is like for social workers can help us rethink approaches to professional development. Workplace learning through direct practice tasks can be part of a cohesive approach to professional learning for social workers in a continually shifting policy context.

This Insight aims to provide social workers – and those concerned with their learning and development – the opportunity to consider ideas from workplace learning theory. This is alongside research and evidence from the experiences of social workers to help shape effective workplace and organisational practices.

Social work learning in context

In the UK, each nation has a different framework and regulatory system for social work education and continuing professional learning, which influences practice, planning for and investment in continuing professional learning (Kettle and colleagues, 2016).

Social work education in Scotland is regulated by the Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC) under the Regulation of Care (Scotland) Act (2001). The SSSC is responsible for the approval of qualifying programmes, continuing professional learning requirements, and the registration of social workers from the point of entry as students.

There is a range of post-qualifying accredited, formal, informal and self-directed learning opportunities available to social workers. Availability and access depend on variable local partnership or individual agency arrangements to deliver, fund or support (Gordon and colleagues, 2019). There is currently no formal post-qualifying learning framework in Scotland, although there are requirements to maintain continuing professional learning for registration as a social worker (SSSC, 2020). However, work is currently underway to explore a framework for Advanced Practice and plans for a Newly Qualified Social Worker Supported Year, each with the complexity of learning for social workers at its heart.

Social work is described as perpetually at the crossroads (McCulloch and Taylor, 2018) and faces a further period of uncertainty as plans and legislation progress for a National Care Service, with yet unknown implications for the profession (Scottish Government, 2022). The position of social work is, therefore, very different to many other professions in terms of resources and consistency in learning and development.

Articulating social work roles and tasks is fraught with ambiguity (Moriarty and colleagues, 2015) and, therefore, it is difficult to articulate what social workers need to learn. Planning to support effective workplace learning strategies is a related further challenge.

Social work learning is usually understood to include the development of skills and competences which enable practitioners to undertake a role which is rooted in human rights and social justice, where ethical practice needs to be negotiated within a work role where there are competing moral, legal, organisational and policy demands.

(Ferguson, 2021, p20)

Influences on social workers’ learning in the workplace

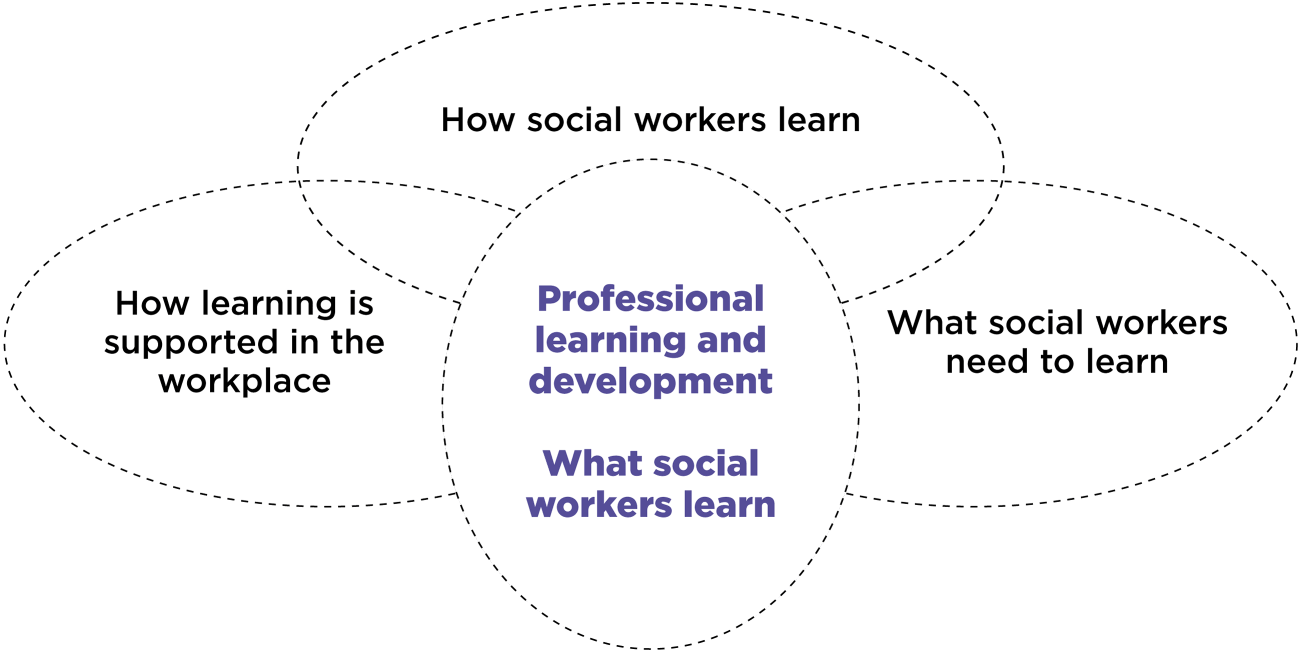

Supporting the continuing professional learning of social workers across their career requires an understanding of the complexity of the role and the needs of these learners (Ferguson, 2021). What social workers learn in the workplace is influenced by how individuals learn, perceptions about what they need to learn, and the ways in which learning is supported in organisations.

A call for integrative and evidence-based approaches to support learning is stressed in a recent final report from a longitudinal study into the experiences of social workers in Scotland (Grant and colleagues, 2022). Evidence from Ferguson (2021) argues that the workplace offers rich opportunities for social workers to learn through their direct practice as part of an essential component of an integrated approach that balances formal, informal and self-directed learning.

Knowledge about learning

The profession of social work draws from evidence and knowledge about learning from broad and divergent perspectives (Smith, 2020). Theories and approaches to understanding individual learning are embedded in professional development, which is acknowledged as a complex, personal process. For example, practice education in social work sets a foundation of experiential and reflective learning. Adult learning theories, such as Andragogy proposed by Malcolm Knowles (1973), highlight learning styles and preferences, and are widely used in social work education. These theories feature as core aspects of practice educator training programmes. Principles of learner autonomy and motivation are central to this.

One’s own practice learning is a key focus of qualifying stages and is emerging again as a focus and priority for ongoing development (SSSC, 2022). Knowledge from research at qualifying and post-qualifying stages shows that learning is often entangled with the respective frameworks or standards in the country in which social workers are registered (Moriarty and Manthorpe, 2014; Daniel and colleagues, 2016; Gordon and colleagues, 2019). Learning in this context can influence the balance of what types of learning are valued by learners and those who are supporting them.

Theories about learning cultures (Schein, 2004) or learning organisations (Senge, 2006) highlight the environment as a fundamental part of workplace learning. The importance of a culture within the workplace that promotes learning has influenced social care leadership initiatives and remains central in practice educator training for social workers. There is also a broad and distinct field of theory about workplace learning and direct evidence from the lived experience of social workers. In this Insight the importance of understanding the work and the place of social work is highlighted to plan effective learning opportunities.

Workplace learning

Workplace learning theories can deepen our understanding of how workplace structures and practices enable professional development. Workplace learning can be formal, informal, incidental or hybrid (Marsick and Watkins, 2003). Additionally, there are different ideas about what is meant by ‘work’, ‘workplace’ and ‘learning’ (Cairns and Malloch, 2011), and how they interrelate and influence social workers’ professional development. Workplaces can also be understood as professional learning environments or communities of practice where knowledge is generated and shared (Lave and Wenger, 1991). The importance of context and significance of the relationship between the learner and their environment is central (Eraut, 2009; Lave and Wenger, 1991).

Places of work are primary sites for learning that are fundamentally different to educational institutions. They can be structured to maximise opportunities, aligned to defined tasks or roles and skill set requirements (Billett, 2001). However, in social work these are notoriously hard to define (Moriarty and colleagues, 2015). Opportunities for working autonomously and the possibilities for interaction between a learner, their work and the environment can trigger learning depending on how work is organised and supported (Felstead and colleagues, 2007). The nature of a workplace can be described as expansive or restrictive in the opportunities that it affords and the practices that it encourages (Engeström, 2001).

Illeris (2011) offers a comprehensive model that demonstrates the complexity of workplace learning and the dynamic processes involved. These dynamic processes include multiple individual and organisational influences on learning through work tasks. The individual dimension interacts with the organisational dimension when work is taking place. Individual influences on learning include the learning content, outcomes, motivations and learner volition. Organisational influences include the technical-rational and social-cultural environments of the workplace, the nature of work, patterns of allocation, distribution and division of labour.

Workplaces are, therefore, complex and important environments for learning as the way that anything is organised within them influences learning possibilities. Social work tasks are very different to those of other professions and social workers find themselves in very diverse workplaces. The combination of theory of workplace learning with social worker practice experience demonstrates the complexity of professional learning.

Conceptualising social workers’ learning in the workplace

Social workers’ learning in the workplace is represented as an intricate web of sensory and emotional experiences that span places, spaces and tasks (Ferguson, 2021). This web involves interwoven themes: ‘journey of the self; navigating landscape and place; navigating tasks; learning through others; learning through the body; practices and conceptions of learning; and learning by chance’ (Ferguson, 2021, p154). The thread of each theme forms unique individual webs that are deeply connected to social workers’ embodied experiences of learning and the type of work opportunities they undertake. This way of understanding social workers’ learning can inform effective strategic policy, and organisational and individual plans for professional development.

Continuous personal learning journeys

Social workers provide rich, detailed evidence of their learning in diverse workplace settings through extraordinary practice tasks where the whole human person is immersed (Ferguson, 2021). Gibbs (2014, p147) outlines the concept of professional development as ‘our becoming’ rather than ‘a curriculum for skills’. The centrality of the whole human person is linked to individual embodied experience and integration of learning into the biography of the person (Jarvis, 2014). Social workers experience their learning in close relation to their personal life, sense of readiness and motivation, as well as issues of professional identity formation (Webb, 2016; Grant and colleagues, 2022). For example, a sense of belonging, or where personal and professional values align.

Social workers can experience a duality of readiness/unreadiness to practise in their early career (Grant and colleagues, 2022). This points to the experience of social workers sometimes feeling ready yet unready in terms of knowledge, skills and experience. Ferguson (2021) found that this could be the case for social workers who had been qualified for decades and not only an early career phenomenon, which reflects expectations of social work practice.

Billet (2001) proposes that in workplace learning the curriculum is individual; the trajectory of the professional learner comprises their biographical and biological development. Some social workers describe the creation of new personas to navigate tasks and roles, whereas others described integrating their personal and professional selves (Ferguson, 2021). The impact on personal life is important for supporting social workers’ professional development.

I suppose like a ball with two bits that intertwine …[that merge] … I think maybe it’s trying to bring the profession and the person into one … there are layers of your professional self, coming together as a social worker with your morals and values every day, but being able to separate them in cases to protect yourself … sometimes I think learning to be a social worker is learning to be you but on a different level

(Caroline, in Ferguson, 2021, p135)

Learning in extraordinary places

Diverse workplaces are central to social workers’ experiences of learning. These workplaces are described as extraordinary, where extreme situations or unusual places become normal for social work practice (Ferguson, 2021). Often workplaces are described as physically or psychologically isolated: ‘in the dark’; ‘feeling like a stranger’; feeling alien’; ‘on your own’; and ‘at night’ (Ferguson, 2021, p158). Physical and psychological isolation is also experienced, even in the presence of others (Ferguson, 2021). Workplace learning environments involve heightened emotional and physical sensory experiences for social workers, which include textures, smells, sounds and sights (Ferguson, 2021).

Examples of workplaces extend beyond the office to include the court; the hospital ward; the sheriff’s house at night; and the home visit. Ferguson (2009) highlights that the home visit is acknowledged as a complex arena in which social workers negotiate the physical boundaries and expectations of their role. They also highlight that atmosphere is a part of the workplace landscape for social work. The workplace or environment of social work is also characterised by non-physical things, including the legislative and policy context, organisational culture, and whether social workers are physically located together in their workspaces (Ferguson, 2021).

Social workers are also learning to practise within the organisational and legislative context. They describe learning to navigate the systems and processes of social work as ‘feeding the system’; ‘managing the conveyor belt’; ‘having to upload to the terminal’; and ‘learning how to be within the system’ as part of their workplace and tasks (Ferguson, 2021, p164).

Learning through complex practice tasks

There are many aspects of social worker tasks that can be best learned through experience. The complexity and uncertainty of the social work role is widely acknowledged (Moriarty and colleagues, 2015; Hood, 2015). Social workers describe the immediacy of this within practice, undertaking tasks that are indescribable and sometimes conflicting or contradictory, and learning to balance and manage these tensions (Ferguson, 2021).

There’s not a rule book you know, we have all got these practice guidelines and things like that but when it comes down to the minutiae there is not a yes or a right answer for lots of things that we do… sometimes if we do the same thing twice some people might say that one was right and that one wasn’t right.

(Boab, in Ferguson, 2021, p92)

How to undertake difficult workplace tasks has to be accommodated as part of the daily job including the ‘serious nature of work, sense of felt responsibility, awareness of power and authority’. Social workers describe not only the challenge of ‘not a normal job’, but the idea that they would then ‘get up and do it again’ (Ferguson, 2021, p163). Social workers described dynamic daily practice that involved ‘life and death’, sometimes literal and often about hugely significant areas of, and decisions about, people’s lives (Ferguson, 2021).

Learning from people supported by social work services

In pre-qualifying formal education, focus is clear about learning from people using social work services through practice learning. Direct work with people who are receiving social work services remains crucial to what social workers learn and how they learn across their career (Ferguson, 2021).

Learning about the reality of life for children, adults and families is striking within social workers’ accounts, including learning about family dynamics and the impact of neglect and abuse across the lifespan. Social workers learn about the importance of understanding the unique lives of people, ‘keeping children alive and safe’, ‘trying to reduce chaos’, ‘trying to be realistic’ and ‘understanding risk’ (Ferguson, 2021). The enormity of decisions and the impact on families are significant aspects of social workers’ experiences.

Assumptions and myths perpetuated by other people, such as the ‘demonisation of parents’, ‘lack of empathy within media’ and ‘interprofessional practice contexts’ are also part of social workers’ workplace learning experiences (Ferguson, 2021).

Learning with other social workers

The influence of other social workers is crucial in workplace learning (Ferguson, 2021). Grant and colleagues (2020) highlight the importance of informal and formal learning with other social workers as fundamental to developing professional identity and learning the specific nuances of practice. Hood (2015) identified development in the professional network of social workers essential to support individual learning.

The organisational landscape influences where social workers are to be found by each other in organisations and in the wider sector. Opportunities to work alongside social workers have changed in the physical environment (Ravalier, 2019). Increased opportunities for multi-professional training provision have also decreased the spaces for safe, specific social work focused learning that is essential for professional development (Ferguson, 2021; Grant and colleagues, 2022). While interprofessional learning is highly valuable for effective practice, there should be sufficient opportunities for social workers to learn together and from each other.

Physical and emotional aspects of learning

Learning through physical and emotional work is a core and complex aspect of social workers’ lived experiences (Ferguson, 2021). Social work is not often associated with physical labour. The body as a vehicle for work was summarised by one social worker as ‘you’re just going in, in your own body’ into situations where other professionals were often paired (Ferguson, 2021, p164).

Emotional intelligence and exposure to emotions are recognised in social work, however, the full extent of emotional labour is not (Ferguson, 2021). Promotion of resilience, mindfulness and trauma-informed practice have brought the body into consciousness in social work practice, learning and support (Kellock, 2018; McCusker, 2020; Rose, 2021). Sensory experiences of sight, smell, sound, touch and taste contribute to learning in the workplace (Ferguson, 2021). Sensory experience and the importance of the senses for deep critical reflection in social work are also stressed by Maclean, Finch and Tedam (2018). Learning through the senses can have specific long-term influences on practice.

You have to think through your senses … thinking about domestic violence, parental substance misuse, what children’s lived experiences are, a lot of that comes through your senses. You can’t pin it down to what you know, to what you see, it’s what you feel, what you smell, all these different things and you know this is just as, if not more, important than some of the bigger grandiose stuff.

(Danny, in Ferguson, 2021, p151)

Ferguson (2018) also found evidence that negative emotions influence social workers’ ability to reflect on practice. Social workers describe learning through work using threat and survival metaphors, feeling ‘taken aback’ by what was encountered, ‘preparing to be annihilated’ in court, and a sense of ‘shock’ (Ferguson, 2021, p165). One social worker used the metaphor ‘sink or swim’, describing at times ‘treading water’, and ‘being frozen’ as part of learning to manage tasks (Ferguson, 2021, p165). Other social workers described being unable to sleep and their ethical and moral tension manifesting in physical anxiety.

Learning by chance

Significant learning in social workers’ careers have been described as down to chance (Ferguson, 2021). This includes where earlier practice learning placements were, subsequent workplaces, the work allocated and the nature of each unique case. Social workers described their learning as ‘it almost kind of depends on where you end up’, ‘who you surround yourself with’ and ‘the kind of conversation you are willing to get into’ (Ferguson, 2021, p173).

Current arrangements for planning and allocating practice learning placements in Scotland are subject to many variables, and experiences are not consistent for students (Daniel and Gillies, 2016). Allocation of tasks is also subject to the multiple variables in team function, manager style, preferences and profile. Variable opportunities and a lack of cohesion in the design of career-long and career-wide learning has an impact on what and how social workers can learn. (Grant and colleagues, 2022). Designing what happens in the workplace can, therefore, have a huge influence on social workers’ learning.

Workplace practices for learning

Understanding what learning in the workplace involves for social workers is important for strategic planning, effective workplace cultures, and plans and procedures. Although learning is acknowledged to be a broad spectrum of activity in rhetoric, standards and policy (SSSC, 2020), plans quickly default to provision or expectations of training as the primary source of continuing professional development (Ferguson, 2022a; Grant and colleagues, 2022).

Formal learning described by social workers in Grant and colleagues’ study appeared to be ‘mandatory, generic, and multi-disciplinary’ (p16) which was regarded as relevant at the induction stage, but less so further into the career. The authors note that successive reviews have reported this without associated change in practices. Research has recently informed national resources that can support effective organisational practices. For example, SSSC guidance for newly qualified social workers and their employers, focuses on how organisations can design workplace tasks; keep learning as the focus; allocate and scaffold tasks, and encourage spaces for social workers to learn (SSSC, 2022).

In Scotland, how learning in the workplace is supported has been subject to changing organisational structures and emphasis. Dedicated profession-specific teams that previously supported learning and development have diminished, reshaped or integrated into generic human resource teams (Kettle and colleagues, 2016: Grant and colleagues, 2022).

Developing fuller and more integrative accounts of learning requires a whole systems approach to improvement where learning is understood and supported as a fundamental feature of professional practice, rather than as an adjunct to it.

(Grant and colleagues, 2022, p18)

Implications for organisational and workplace practices

There are key implications for those involved in supporting social workers’ learning across their career:

- All modes of professional development are important, however, workplace learning opportunities should be recognised as essential

- Workplace learning for social workers can be enhanced by focusing on the way work is allocated, supported and recognised as contributing to learning in organisations and teams

- Articulating the complexity of learning for social workers gives insight into daily social work practice – social workers are undertaking extraordinary tasks in diverse workplaces

- Emotional and physical aspects of learning need to be acknowledged in social workers’ professional learning – how these are integrated in any virtual or simulated alternatives to direct practice learning is important

- Opportunities for social workers to learn together and from each other are vital

- Social workers’ professional learning should not be subject solely to chance – effective overarching frameworks, organisational resourcing and planning in line with other professions can integrate workplace learning as part of cohesive approaches.

References

- Billett S (2001) Learning through work: workplace affordances and individual engagement. Journal of Workplace Learning, 13, 5/6, 209-14

- Cairns L and Malloch M (2011) Theories of work, place and learning: new directions. In Malloch M, Cairns L and Evans, K The SAGE handbook of workplace learning. London: Sage, 3-16

- Daniel B, Eady S, Engstrom S et al (2016) Revised standards in social work education and a benchmark standard for newly qualified social workers. Stirling: University of Stirling

- Engeström Y (2001) Expansive learning at work: toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14, 1, 133-156

- Eraut M (2009) Transfer of knowledge between education and workplace settings. Knowledge, Values and Educational Policy: A Critical Perspective, 65

- Felstead A, Fuller, A, Unwin L et al (2005) Surveying the scene: learning metaphors, survey design and the workplace context. Journal of Education and Work, 18, 4, 359-383

- Ferguson H (2009) Performing child protection: home visiting, movement and the struggle to reach the abused child. Child and Family Social Work, 14, 4, 471-480

- Ferguson H (2018) How social workers reflect in action and when and why they don’t: the possibilities and limits to reflective practice in social work. Social Work Education, 37, 4, 415-427

- Ferguson GM (2021) “When David Bowie created Ziggy Stardust”. The lived experiences of social workers learning through work. The Open University

- Ferguson GM (2022a) Reconceptualising how social workers learn in the workplace. WELS PGR research blog post

- Ferguson GM (2022b) Influences on professional learning in the workplace. In Scottish Social Services Council (2022) Promoting NQSW learning and development in the supported year

- Gibbs P (2014) The phenomenology of professional practice: a currere. Studies in Continuing Education, 36, 2, 147-159

- Gordon J, Gracie C, Reid M et al (2019) Post-qualifying learning in social work in Scotland: a research study. Dundee: Scottish Social Services Council

- Grant S, McCulloch T, Daly M et al (2020) Newly qualified social workers in Scotland: a five-year longitudinal study Interim Report 4. Dundee: Scottish Social Services Council

- Grant S, McCulloch T, Daly M et al (2022) Newly qualified social workers in Scotland: a five-year longitudinal study final report. Dundee: Scottish Social Services Council

- Hood R (2015) How professionals experience complexity: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Child Abuse Review, 24, 2, 140-152

- Illeris K (2011) The fundamentals of workplace learning. London: Routledge

- Jarvis P (2014) From adult education to lifelong learning and beyond. Comparative Education, 50, 1, 45-57

- Kellock J (2018) Living a mindful life:an hermeneutic phenomenological inquiry into the lived experience of secular mindfulness, compassion and insight. PhD Thesis, Aberdeen: University of Aberdeen

- Kettle M, McCusker P, Shanks L et al (2016) Integrated learning in social work: a review of approaches to integrated learning for social work education and practice. Glasgow: Glasgow Caledonian University

- Knowles MS (1973) The adult learner. A neglected species. Houston: Gulf Publishing

- Lave J and Wenger E (1991) Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Maclean S, Finch J and Tedam P (2018) SHARE: A new model for social work. Staffordshire: Kirwin Maclean Associates Ltd

- Marsick VJ and Watkins KE (2001) Informal and incidental learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2001, 89, 25

- McCulloch T and Taylor S (2018) Becoming a social worker: realising a shared approach to professional learning? British Journal of Social Work, 48, 8, 2272–2290

- McCusker (2020) Mindfulness in social work education and practice. Insight 56. Glasgow: Iriss

- Moriarty J and Manthorpe J (2014) Post-qualifying education for social workers: a continuing problem or a new opportunity? Social Work Education, 33, 3, 397-411

- Moriarty J, Baginsky M and Manthorpe J (2015) Literature review of roles and issues within the social work profession in England. London: Social Care Workforce Research Unit, King's College

- Ravelier JM (2019) Psycho-social working conditions and stress in UK social workers. British Journal of Social Work, 49. 2, 371-390

- Regulation of Care (Scotland) Act (2001), HMSO, London

- Rose S (2021) Creating a culture of resilience for social workers. Insight 58. Glasgow: Iriss

- Schein EH (2004) Organizational culture and leadership. 3rd Edition. San Francisco: Jossey Bass

- Scottish Government (2022) National Care Service

- Scottish Social Services Council (2020) Continuing professional learning requirements (CPL) guidance. Dundee: Scottish Social Services Council

- Scottish Social Services Council (2022) Promoting NQSW learning and development in the supported year.

- Senge PM (2006) The fifth discipline: the art and practice of the learning organization. London: Random House

- Smith M (2020) It really does depend: towards an epistemology (and ontology) for everyday social pedagogical practice. International Journal of Social Pedagogy, 9, 1, 18

- Wenger-Trayner E and Wenger-Traynor B (2015) Learning in a landscape of practice: a framework. In Wenger-Traynor E, Fenton-O’Creevy M, Hutchinson S et al (eds) Learning in landscapes of practice: boundaries, identity, and knowledgeability in practice-based learning. London: Routledge

- Webb S (2016) Professional identity and social work: The Routledge companion on the professions and professionalism. London: Routledge

Acknowledgements

This Insight was reviewed by Helen Allbutt (NHS Education for Scotland), Scott Grant (University of the West of Scotland), Trish McCulloch (University of Dundee) and Ruth Shipstone (Dumfries and Galloway Council).

Comments represent the views of reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of their organisations. Iriss would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time to reflect and provide feedback on this publication.

About the author

Gillian Ferguson is a Lecturer in Social Work with The Open University working on the production and presentation of professional programmes. She has worked in a broad variety of settings including direct practice, workforce development, advisory and regulatory roles, including as a social worker, community learning worker and academic. She previously led the practice educator qualification for the Tayforth Partnership. Gillian’s research with social workers in the workplace shows her interest and commitment to learning from lived experiences. Gillian is a registered social worker and stays closely connected to practice through involvement with a third sector addictions service in Tayside.

Credits

- Series Coordinator: Kerry Musselbrook

- Commissioning Editor: Kerry Musselbrook

- Copy Editor: Michelle Drumm

- Designer: Ian Phillip