Key points

- It is ten years since the publication of the first national strategy for Self-directed Support (SDS)

- Evidence, both from scrutiny activity and research, indicates a very mixed picture of delivery across Scotland, with some people benefitting and others not having full access

- Processes for delivery of SDS are often bureaucratic and unwieldy, with the voice of the supported person not being fully heard

- In order for the goals of the SDS strategy to be fully implemented, a change of culture will be required to fully put the voice of the supported person at the heart of SDS processes

- There are significant implications for the workforce in terms of training and autonomy; real investment in education and training is required

Introduction

It is ten years since the Scottish Government produced the first national strategy for SDS (Scottish Government, 2010) and seven years since the passing of the Social Care (Self-directed Support) (Scotland) Act 2013. At the time of writing, the Independent Review of Adult Social Care (IRASC) has been published (Scottish Government, 2021) and the final version of national standards for SDS is imminent (Social Work Scotland, 2019). Both of these are intended to bring about significant change.

This Insight seeks to explore the background to the development of SDS in Scotland, summarise the evidence from policy and scrutiny activity, and consider the future direction of SDS policy and practice. Further, it will explore the dominant narratives and themes found within the literature. It is important at the outset to acknowledge that inconsistency is a major challenge faced in the delivery of SDS (Audit Scotland, 2017; Care Inspectorate, 2019).

Background

Scotland’s approach to SDS is guided by a range of policy drivers, namely the SDS ten-year national strategy (Scottish Government, 2010), the SDS Implementation Plan (Scottish Government, 2019b) and most recently the IRASC (Scottish Government, 2021). The Scottish Government definition of SDS identifies a number of key features:

- Choice and control

- Co-production

- Agreement of individual outcomes

- A range of options to achieve those outcomes

The Social Care (Self-Directed Support) (Scotland) Act 2013 came into effect in April 2014 and introduced new legal duties for local authorities (LAs) outlined in the statutory guidance (Scottish Government, 2014, p9-11), including to:

- Have regard to the general principles of collaboration, informed choice and involvement as part of the assessment and the provision of support

- Take reasonable steps to facilitate the person's dignity and participation in the life of the community

- Offer four options to the supported person

- Explain the nature and effect of the four options and to ‘signpost’ to other sources of information and additional support

The SDS Act, therefore, places a duty on LAs to conduct the assessment of need in collaboration with the supported person and relevant individuals. If the supported person has been assessed by the LA as having identified needs and requiring a budget, they then should be offered the four options on how to spend this budget:

- A Direct Payment to the individual

- An arrangement where the supported person chooses their own support, but someone else arranges that support and manages the budget (sometimes via an Individual Service Fund)

- The LA manages support and budget on behalf of the supported person

- A mix of these

Additionally, there is an expectation that the following values will be considered: respect; fairness; independence; freedom; and safety (Scottish Government, 2014). This next section summarises the evidence to date on SDS from both scrutiny activity and empirical research.

Current evidence

There has been considerable scrutiny of SDS including the Care Inspectorate’s (2019) thematic inspection, a government commissioned SDS implementation study (Scottish Government, 2019a), an Audit Scotland report (2017) and the Scottish Parliament’s Public Audit and Post-Legislative Scrutiny Committee report (2017). Although these reviews each recognise the positive transformative potential of the policy, their findings identify many of the same concerns including:

- A limit to the extent to which people have choice and control

- Bureaucracy of processes and procedures

- Lack of transparency and recording

- A lack of the true availability of all four options

- The level of co-production

- Inconsistent knowledge across the workforce

In particular, although it has been ten years since the initial SDS strategy, the thematic inspection concluded that ‘most partnerships had yet to fully implement SDS, meaning that its true potential was not being realised’ (Care Inspectorate, 2019, p9). Therefore, it is reasonable to ask why the goals of the initial strategy have not been achieved.

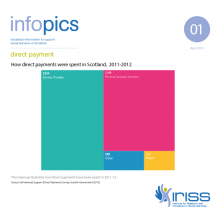

Meaningful choice

The available evidence indicates a very mixed picture with regard to choice and control. The recent Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland/Self Directed Support Scotland (hereafter ALLIANCE/SDSS), (2020c) report indicates that for those people who have access to SDS, it can work very well. Theoretically the four options enable the supported person to mix traditional services with a personalised approach, therefore, offering greater flexibility, choice and control over care arrangements (Rummery and colleagues, 2012). However, evidence suggests that the traditional care culture has been difficult to shift and that little has changed with regards to the type of services people are receiving (Pearson and Ridley, 2017; Pearson and colleagues, 2018). It has been found that option 3, direct delivery of services by the LA, remains the dominant SDS provision (Pearson and Ridley, 2017; Pearson and colleagues, 2018). This was reinforced by the thematic inspection, which indicated that option 1 is generally well established, however, option 3 was most easily available. Furthermore, access to option 2 and 4 remained limited (Care Inspectorate, 2019).

Option 2 enables the supported person to direct how the budget will be spent without managing the daily finances, reducing personal risk, while creating the potential for innovative care with greater choice and control for the individual (Kettle, 2015; Dalrymple and colleagues, 2017). An absence of central direction on implementation of option 2 has resulted in considerable disparity in understanding amongst practitioners, causing challenges for those managing delivery (Kettle, 2015; Manthorpe and colleagues, 2015; Pearson and colleagues, 2018).

The principles of SDS clearly state that staff should support decision making through co-production rather than make decisions on behalf of individuals. The ALLIANCE/SDSS report (2020c) revealed that over a third of people felt free to choose their own support, and a quarter of people had their care chosen by family or friends. However, 27% stated professionals chose for them. Furthermore, the research (2020, p50) stated that ‘some interviewees felt that their social worker had decided what SDS option they would choose before completing the needs assessment’. Social work staff failing to discuss and offer all four options is a common issue which appears elsewhere in the literature (Mitchell, 2015; Fleming and Osborne, 2019). Additionally, insufficient recording of discussions between the worker and the supported person makes it impossible to determine the extent of choice and control being delivered, to monitor achievement of personal outcomes or evaluate progress (Care Inspectorate, 2019).

The importance of support networks, independent advocacy and accessible accurate information has been identified as central to enhancing choice and control (Mitchell, 2015; Care Inspectorate, 2019; ALLIANCE/SDSS, 2020c). However, overall, there is a lack of awareness regarding advocacy amongst professionals and supported people, combined with advocacy services struggling to meet demand (Care Inspectorate, 2019; ALLIANCE/SDSS, 2020c). Similarly, brokerage is underused and could also increase impartial independent information and support people to find creative solutions. The IRASC recommends enhancing services for both independent advocacy and brokerage (Scottish Government, 2021). Furthermore, the recent announcement to reopen the Independent Living Fund (ILF) is also hoped to increase choice, control and partnership working (Scottish Government, 2021).

A mainstream approach

A recurring concern raised in the literature is the level to which SDS has become the mainstream approach to social care delivery as has been intended, and whether there are groups of people who do not gain access to SDS (Audit Scotland, 2017; Dalrymple, 2017). Overall, there has been a lack of robust data gathering regarding experiences of SDS. For example, the ALLIANCE/SDSS report (2020) found that people who are homeless are excluded from SDS. In addition to this report, separate research reports have been conducted which focus on the experiences of: women as users of SDS (2019); people with lived experiences of mental health (2020e); black and minority ethnic people (2020a); blind and partially sighted people (2020b) and people with learning disabilities (2020d). Although it is beyond the scope of this Insight to detail the findings from each report, it is evident more work is required to understand and remove barriers to SDS faced by specific client groups.

Dual discourses

Hunter and colleagues (2012) outline the dual discourses of SDS and adult support and protection (ASP) within Scotland when supporting adults at risk. The impact that these parallel pieces of legislation have on each other, specifically the tension between empowerment and protection remains under-explored. Although there is limited research within the Scottish context, there are a series of recent linked papers exploring the relationship between safeguarding and personalisation in England (Steven and colleagues 2014; Manthorpe and colleagues, 2015; Ismail and colleagues, 2017; Stevens and colleagues, 2018; Aspinal and colleagues, 2019). Manthorpe and colleagues (2011, p.435) describes personalisation and safeguarding as operating on ‘parallel tracks’ emphasising the disjuncture and possible competing philosophies between the policies. Further research is required to consider how practitioners navigate the complex risk management process, and how safeguarding legislation, potentially impacts the choice, control and empowerment experienced by the supported person when coproducing assessments and care plans.

Multiple languages

Prior to SDS, the traditional provision of care was task-focussed, which was deemed disempowering and deficit-focussed with limited emphasis on the supported person’s wishes (Witcher, 2014; Manji, 2018). In line with the social model of disability, SDS represents a deliberate attempt to shift the culture of practice towards co-production of an outcome-focussed provision, underpinned by a human rights-based approach (Scottish Government, 2021). The importance of language and dialogue has also been highlighted within the SDS Implementation Plan 2019-2021 (2019b). This outlines the value of good conversations between workers and supported people to enable effective identification of outcomes. It aims to have the person and their aspirations for social care at the centre of planning, and give them more choice, control and flexibility (Manji, 2018). However, current evidence demonstrates that this is yet to be fully realised. The ALLIANCE/SDSS report (2020c) identifies that while some experienced consistent and clear communication, others spoke about misinformation, lack of transparency, and a failure to communicate all four options.

Critchley and Gillies (2018, p27) found that bureaucratic processes influence the actions and dialogue of SDS work, highlighting that frontline staff continue to speak a “language of ‘hours’ under a ‘time and task’ model rather than emphasising individual budgets and creativity”. Similarly, the thematic inspection (2019, p10) states that workers converse in ‘two different languages’. Staff speak one language when working with the supported person, however, when completing assessments and seeking resources they communicate in a language of deficits, consequently contradicting the philosophy, principles and values of SDS. Processes and procedures need to support the outcomes focussed conversation, rather than pulling discussions back to deficit language.

Processes and systems

A recurring theme across the literature is high levels of bureaucracy. This includes long waiting lists for assessments and a lengthy assessment process. Once the assessment is completed there can be extensive layers to the decision-making process for a budget to be authorised, as well as a review process that is drawn-out or absent (Mitchell, 2015; Care Inspectorate, 2019). Further, local interpretation of national policy has resulted in a complex landscape of SDS procedures, processes and systems (Audit Scotland, 2017). Social workers face dual imperatives to convey that SDS is personalised and flexible, while at the same time facing inflexible organisational processes (Manthorpe and colleagues, 2015). Evidence suggests that tensions arise where the systems and processes limit the ability to fully implement SDS, resulting in a systems-led approach rather than a focus on outcomes (Care Inspectorate, 2019; Scottish Government, 2021). This systems-led approach not only contradicts the philosophy of the policy and limits choice and control for the supported person, but often results in the practitioner feeling a sense of powerlessness and lack of autonomy (Manthorpe and colleagues, 2015; Audit Scotland, 2017; Care Inspectorate, 2019).

Eligibility criteria and resource allocation systems

Eligibility criteria is a framework used by the local authority to determine whether an individual meets the threshold to access formal support (Slasberg and Beresford, 2016; Slasberg and Beresford, 2017). The National Eligibility Framework classifies risk as: critical risk; substantial risk; moderate risk; and low risk. Once an assessment has been completed, the resource allocation system (RAS) set of rules is used to determine the correlating individual budget (Duffy, 2010). Rummery and colleagues (2012) highlight considerable variation amongst the assessment forms, eligibility criteria and RAS process in different LAs, as well as inconsistencies regarding guidelines on what a budget can be spent on. The local interpretation of eligibility criteria and the creation of different RAS systems has resulted in the national policy of SDS being implemented under thirty-two separate systems (Eccles, 2018). Literature highlights the lack of transparency in relation to the decision-making and the allocation of resources, leading to the supported person feeling removed from these processes, which they feel hinders their choice and control (Audit Scotland, 2017; Dalrymple and colleagues, 2017; Care Inspectorate, 2019; ALLIANCE/SDSS, 2020c).

Currently austerity measures have resulted in limited resources and high thresholds for accessing support. A recent legal challenge, Mrs Q v Glasgow City Council (2018) CSIH 5, highlights the controversy over the maximum allocation of resources to support an individual in the community. The power of attorney (POA) for the supported person (Mrs Q) argued that the LA should pay for Mrs Q’s one-to-one care at home in the community. Additionally, the POA contended that the LA failed to perform the statutory duty of providing appropriate services under section 12A of the Social Work (Scotland) Act 1968. Glasgow City Council, however, were of the view that Mrs Q required 24-hour care and these needs could be met within a residential care home, thus, the SDS budget for care in the community matched the cost of the care home. The court upheld the decision of the LA and this case law has set a precedent for providing social care which does not exceed the cost of a residential placement for those aged 65 years old or above. It is likely that more cases will come before the courts.

Dalrymple and colleagues (2017, p20) argue that, “cost pressures add to a sense that SDS is, per se, ‘too expensive’; and are used to justify proposals […] to forcibly replace ‘community care’ with ‘residential care’ when the cost of the former exceeds the average cost of the latter”. Exploration of how threshold decisions are reached and justified is required to avoid arbitrary interpretations of the legislation combined with transparency for the supported person. The IRASC makes the recommendation that all eligibility criteria and charging regimes need to be fundamentally reformed and removed, highlighting that social workers should be focused on the rights of the service user, rather than hampered by considerations of eligibility (Scottish Government, 2021).

Austerity

Within the research literature, there is a strong sense that personalisation policies have been divisive, and use the language and philosophies of disability activism, while promoting neo-liberal ideologies (Ferguson, 2012; Pearson and colleagues, 2014). Pearson and colleagues (2018) argue that Scotland’s social care budget has fallen in real terms, creating an environment of limited resources which has impeded the effective delivery of SDS. This literature cautions against the marketisation of care, arguing it undermines the philosophy of SDS. Research recognises the growing expectation for the supported person to pay towards the cost of their own social care, and confusion as to what is or is not included under free personal care (Manji, 2018; ALLIANCE/SDSS, 2020c). Recently, the IRASC set out the recommendation to end all non-residential charges. Additionally, the report recommends that accountability for social care support should move from local government to Scottish Ministers, and that the National Care Service (NCS) should oversee local commissioning and procurement alongside reformed Integration Joint Boards. It emphasises reframing social care as an investment, rather than a burden, and shifting the narrative from competitive to collaborative commissioning. Thus, decisions should be centred on the person’s needs, not the market. At the time of writing it is unclear what the response of the Scottish Government will be to IRASC.

Workforce knowledge

There is some suggestion that the health and social care integration agenda has diverted attention away from SDS and stalled its implementation (Audit Scotland, 2017). An integrated workforce should complement the integral SDS concepts of partnership working and coproduction, however, concerns have been raised regarding awareness, understanding, training and involvement from health professionals (Pearson and colleagues, 2018; Care Inspectorate, 2019; ALLIANCE/SDSS, 2020c). Training of staff, including social workers is known to be valuable (Manthorpe and colleagues 2015), however, little is known about the quality of training provided within each health and social care partnership. It is apparent that significant progress is still required to strengthen frontline understanding of SDS. Consideration must be given to how SDS is integrated into the education curriculum across Scotland to ensure practitioners are informed prior to entering the workplace.

The IRASC recommends a new national organisation for training and development, improvement of working conditions, implementing the Fair Work Convention, and the real living wage (Scottish Government, 2021). Investment in the workforce is viewed as crucial to improving gender equality given the social care workforce is 83% female (Scottish Government, 2021).

SDS and COVID-19

Clearly, the pandemic has impacted on the delivery of social care. The emergency Coronavirus Act 2020 was introduced to help respond to the demands caused by COVID-19 (Scottish Government, 2020b). The Scottish Government provided £100m additional funding towards health and social care partnerships to help sustain social care support (Scottish Government, 2020a). The Scottish Human Rights Commission found that disabled and older people’s human rights had been compromised as a result of the reduction of support during the pandemic. The report also urged LAs to restore care packages which have been removed without dialogue with the individual or an assessment process (SHRC, 2020). Parallels can be made to research by Dickinson and colleagues (2020) who argue that the pandemic has exasperated many of the underlying problems and limitations of personalisation policies.

Implications for social work practice

At the time of writing, the IRASC evidenced the government’s commitment to improving SDS delivery within a reformed system, specifically outlining the case for a National Care Service (Scottish Government, 2021). The final version of SDS standards are awaited (Social Work Scotland, 2019). Both IRASC and the draft standards address a number of themes identified in this Insight, and are underpinned by four assumptions, namely:

- Taking a human rights-based approach to assessment support planning and review processes

- Focusing on community supports

- Systems and processes being aligned to SDS values and principles

- Shifting from a crisis focus to a preventative focus

What is clear from the above review of the evidence is that while there is some cause for cautious optimism, a significant shift of culture will be required if the original aspirations of the original SDS strategy are to be fully achieved. This will involve change in the processes by which SDS arrangements are made that genuinely shifts choice and control to the supported person, as well a workforce that is fully equipped and has greater autonomy to make decisions to support that.

References

- Aspinal F, Stevens M, Manthorpe J et al (2019) Safeguarding and personal budgets: the experiences of adults at risk. The Journal of Adult Protection, 21, 157–168

- Audit Scotland (2017) Self- directed support: 2017 progress report. Edinburgh: Audit Scotland

- Care Inspectorate (2019) Thematic review of self-directed support in Scotland: transforming lives. Dundee: Care Inspectorate

- COSLA (2020) National strategy and guidance: charges applying to social care support for people at home. Edinburgh: COSLA

- Critchley A and Gillies A (2018) Best practice and local authority progress in self-directed support. Edinburgh: Social Work Scotland

- Dalrymple J, Macaskill D and Simmons H (2017) Self-directed support: your choice, your right. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform

- Dickinson H, Carey G and Kavanagh AM (2020) A personalisation and pandemic: an unforeseen collision course? Disability and Society, 35, 1012–1017

- Duffy S (2010) Future of personalisation. Sheffield: Centre for Welfare Reform

- Eccles A (2018) Integrated working, pp88-201. In Cree V and Smith M (eds) Social work in a changing Scotland. London: Routledge

- Ferguson I (2012) Personalisation, social justice and social work: a reply to Simon Duffy. Journal of Social Work Practice, 26, 55-73

- Fleming S and Osborne S (2019) The dynamics of co-production in the context of social care personalisation: testing theory and practice in a Scottish context. Journal of Social Policy, 48, 671-697

- Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland and Self-directed Support Scotland (2019) Women’s experiences of SDS and social care. Glasgow: The ALLIANCE and SDSS

- Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland and Self-directed Support Scotland (2020a) Black and minority ethnic people’s experiences of SDS and social care. Glasgow: The ALLIANCE and SDSS

- Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland and Self-directed Support Scotland (2020b) Blind and partially sighted people’s experiences of SDS and social care. Glasgow: The ALLIANCE and SDSS

- Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland and Self-directed Support Scotland (2020c) My Support, My Choice: user experiences of SDS in Scotland. Glasgow: The ALLIANCE and SDSS

- Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland and Self-directed Support Scotland (2020d) People with learning disabilities’ experiences of SDS and social care. Glasgow: The ALLIANCE and SDSS

- Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland and Self-directed Support Scotland (2020e) People with mental health problems’ experiences of SDS and social care. Glasgow: The ALLIANCE and SDSS

- Hunter S, Pearson C and Witcher S (2012) Self-Directed Support (SDS): preparing for delivery. Iriss

- Ismail M (2017) Do personal budgets increase the risk of abuse? Evidence from English national data. Journal of Social Policy, 46, 291-311

- Kettle M (2015) Self-directed support–an exploration of option 2 in practice. Edinburgh: Providers and Personalisation

- Manji K (2018) ‘It was clear from the start that [SDS] was about a cost cutting agenda' exploring disabled people's early experiences of the introduction of self-directed support in Scotland. Disability and Society, 33, 1391-1411

- Manthorpe J, Hindes J, Martineau S et al (2011) Self-directed support: a review of the barriers and facilitators. Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- Manthorpe J, Martineau S, Ridley J et al (2015) Embarking on self-directed support in Scotland: a focused scoping review of the literature. European Journal of Social Work, 18, 36-50

- Mitchell F (2015) Facilitators and barriers to informed choice in self-directed support for young people with disability in transition. Health and Social Care in the Community, 23, 190-199

- Mrs Q v Glasgow City Council (2016) CSOH 137

- Needham G (2015) Personalisation – love it or hate it? Journal of Integrated Care, 23, 268–276

- Pearson C and Ridley J (2017) Is personalization the right plan at the wrong time? Re-thinking cash-for-care in an age of austerity. Social Policy and Administration, 51, 1042-1059

- Pearson C, Watson N and Manji K (2018) Changing the culture of social care in Scotland: has a shift to personalization brought about transformative change? Social Policy and Administration, 52, 662-676

- Pearson C, Ridley J and Hunter S (2014) Self-directed support: personalisation, choice and control. Edinburgh: Dunedin

- Rummery K, Bell D, Bowes A et al (2012) Counting the cost of choice and control: evidence for the costs of self-directed support in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- Scottish Government (2010) Self-directed support: a national strategy for Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- Scottish Government (2014) Statutory guidance to accompany the social care (Self-directed Support) (Scotland) act 2013. Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- Scottish Government (2019a) Self-directed support implementation study 2018. Report 4: summary of study findings and implications. Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- Scottish Government (2019b) Self-directed support strategy 2010-2020: Implementation Plan 2019-2021. Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- Scottish Government (2021) Independent Review of Adult Social Care in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- Scottish Government (2020a) Further £50 million for social care sector. Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- Scottish Government (2020b) Coronavirus (COVID-19): changes to social care assessments. Statutory guidance for local authorities on sections 16 and 17 of the Coronavirus Act 2020. Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- Scottish Human Rights Commission (2020) Covid-19, social care and human rights: impact monitoring report. Edinburgh: Scottish Human Rights Commission

- Scottish Parliament’s Public Audit and Post-legislative Scrutiny Committee (2017) PAPLS committee meeting. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Slasberg C and Beresford P (2016) The eligibility question – the real source of depersonalisation? Disability and Society, 31, 969-973

- Slasberg C and Beresford P (2017) The need to bring an end to the era of eligibility policies for a person-centred, financially sustainable future. Disability and Society, 32, 1263-1268

- Social Care (Self-directed Support) (Scotland) Act 2013.

- Social Work Scotland (2019) Proposed National Framework for Self-directed Support. Edinburgh: Social Work Scotland.

- Stevens M, Aspinal F, Woolham J et al (2014) Risk, safeguarding and personal budgets: exploring relationships and identifying good practice. London: NIHR School for Social Care Research

- Stevens M, Woolham J, Manthorpe J et al (2018) Implementing safeguarding and personalisation in social work: Findings from practice. Journal of social work, 18, 3–22

- Witcher S (2014) My choices: a vision for self-directed support. Glasgow: Glasgow Disability alliance

Acknowledgements

This Insight was reviewed by Helen Allbutt (NHS Education for Scotland); Calum Carlyle, Donna Murray, Jane Kellock and Ailsa Mcallister (Social Work Scotland); Donald Macleod (Self-directed Support Scotland); Lucy Mulvagh and Hannah Tweed (Health and Social Care Alliance); and Charlotte Pearson (University of Glasgow). Comments represent the views of reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of their organisations. Iriss would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time to reflect and comment on this publication.