Key points

- Criminal Justice Social Work (CJSW) practitioners work on a daily basis with people convicted of hate crime and/or display prejudice, but there is a lack of specific Scottish research on effective practice in this area.

- From the existing research, hate crime interventions are best undertaken one-to-one, incorporating cultural/diversity awareness, anger/emotion management, hate crime impact and restorative justice.

- People convicted of hate crime frequently experience adverse circumstances and may have unacknowledged shame, anger, and feelings of threat and loss.

- Practitioners should develop relationships with people who commit hate offences characterised by acceptance, respect, and empathy, without judgement or collusion. This supports positive change, balanced with the responsibility for protecting the public from further harm.

Introduction

Hate crime can have a devastating impact on individuals, families, communities and the very fabric of society. However, there is a remarkable dearth of research on the most effective ways to work with people who have committed this type of offence, particularly for Criminal Justice Social Work (CJSW) services and practitioners responsible for their supervision and rehabilitation. This Insight aims to consolidate some of the existing research on effective practice with people who commit hate offences, firstly defining and describing hate crime and its root causes, and then considering what may constitute effective practice for practitioners in Scotland working in this field.

Definitions and scope

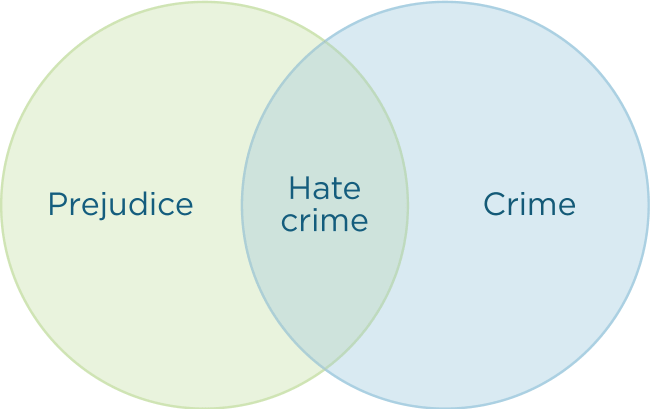

What is ‘hate crime’?

Hate crime is defined in Scotland as ‘a crime motivated by malice or ill will towards a social group’, with five ‘protected characteristics’ in current Scottish legislation – race, religion, disability, sexual orientation and transgender identity. Unsurprisingly, there are definitional issues with this term, including the concept of ‘hate’ itself, and the socially constructed nature of hate crime (Walters, 2016; Awan and Zempi, 2018). Notwithstanding this, ‘hate crime’ will be used throughout this Insight as the most broadly-used term.

Hate crime ranges from verbal abuse, criminal damage, violence, sexual assault and murder. It is not always committed by strangers; many victims of hate crime know the perpetrator(s) (Mason, 2005). It can also occur online (arguably in greater numbers than offline), creating issues around policing and responsibility (Rohlfing, 2015).

Scope

Annual data published by the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service demonstrates that hate crime is an ongoing issue in Scotland, with 4914 reported offences in 2018–19 (COPFS, 2019), and 1323 convictions for hate crime in 2017–18 (Scottish Government, 2019a). Information from the Scottish Prison Service indicates that there are currently 883 people in custody convicted of hate crime across the prison estate (Fletcher, 2019). However, there is a broad consensus that hate crime is significantly under-reported (Chakraborti, 2017).

Impact

Research indicates that hate crime is more harmful to victims and communities than other types of offending (Iganski and Lagou, 2015). The emotional and psychological trauma caused by hate crime can be intensified, and vicarious trauma can be experienced by those who share identity characteristics with the person involved, such as family or community members. Victims of hate crimes are more likely than victims of parallel crimes to report higher levels of anger, anxiety, sleep difficulties and suicidal ideation (ibid).

Iganski and colleagues (2015) emphasise that any rehabilitative interventions with those who commit hate crime should seek to develop their understanding of the harms it causes, indicating that many people are not fully aware of the impact of their actions at the time of committing the offence; it follows that practitioners should also have a robust understanding of this.

Legislation and policy

The Criminal Law (Consolidation) (Scotland) Act 1995 Section 50A specifically refers to the offence of ‘racially aggravated harassment’, with religiously aggravated offences covered by Section 74 of the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2003. The Offences (Aggravated by Prejudice) (Scotland) Act 2009 (sections 1 and 2) were implemented in 2010, covering sexual orientation, transgender identity and disability aggravated offences. Reporting on the ostensible shortcomings of current Scottish hate crime legislation, the Independent Advisory Group (2016) recommended a review, including consideration as to whether additional protected characteristics are necessary such as gender and age. The legislative review recently completed the public consultation phase and consolidated hate crime legislation will be presented before the Scottish Parliament this year (Scottish Government, 2019b).

The Scottish Government established the ‘Tackling Prejudice and Building Connected Communities Action Group’ to advance the recommendations of the Independent Advisory Group’s report; there are also long-established policies specifically relating to tackling sectarianism. The national Prevent strategy accounts for Section 26 of the Counter Terrorism and Security Act (2015), which places a duty on local authorities to have ‘…due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism…’ (Scottish Government, 2015), with local authorities (including social workers) working closely with the police, education and health.

Those involved in community planning and improvement partnerships have also identified varying actions, outcomes and improvement indicators to reduce hate crime at local level. Nonetheless, from a review of these types of policy documents and the relevant literature, there is no mention of CJSW services and their key role in striving to tackle hate crime and its impact.

Causes of hate crime

Some of the key causal mechanisms are now briefly presented, particularly those that may be of greater relevance for practitioners.

Shame and anger

In their study of people convicted of racially aggravated offences against Asian people in Manchester, Ray and colleagues (2004, p350) posit that racist violence ‘…can be understood in terms of unacknowledged shame and its transformation into fury’ by those experiencing multiple disadvantage. Perpetrators regard themselves as ‘weak’ and unfairly treated by their victims, who they regard as illegitimately successful within a violent and racist cultural context. These feelings of shame are projected onto others, who become scapegoats. Shame can also be associated with homophobic assaults and targeting people with disabilities. It is exacerbated by conflict situations and the perpetrators generally being more likely to ‘explode in crisis situations’ (Roberts and colleagues, 2013), as well as the attribution of stereotypes and notions of certain groups ‘deserving’ ill-treatment (Lyons, 2006).

Masculinity and ‘toxic masculinity’

Holland and Scourfield (1999, p134) contend that ‘…most front-line criminal justice personnel spend most of their time working with marginalised men…’, being especially true of probation (and CJSW) staff. Trickett (2015a, p261), in her study of young male unemployed hate crime perpetrators in Birmingham who targeted Asian male shopkeepers, posits that they were attempting to assert their masculine identity, motivated by hostility against ‘difference’ and socio-economic strain. However, both were importantly linked to the perceived threatened masculinity of the perpetrator. Allison and Klein (2019, p3) highlight similar themes around ‘hegemonic masculinity’ in their examination of the targeted murders of homeless people in the USA.

This relates to ‘toxic masculinity’: ‘…a set of very narrow standards, behaviours, and expectations for manhood and masculinity that values dominance, power, and control…’ (Thompkins-Jones, 2016). Haider (2016), referring to the homophobic shootings in Orlando, states that toxic masculinity and violence serve to ‘police’ the patriarchal order, which allows no room for diverse sexualities and genders. Theories on masculinity, however, do not adequately account for women’s participation in hate offending.

Family, community and education

McBride (2015, p11-12) argues that ‘most of our prejudices are learned at a young age’, with Walters (2015, p402) highlighting ‘...a source of offender’s bigotries may be their own community’. Dixon and Court (2015, p381) describe ‘community profiles’ which produce racial offending, with factors such as: ‘…entrenched local racism; local social and economic deprivation; passive engagement in leisure activities; few affordable youth facilities; high levels of adult criminality linked with wider criminal networks; and violent youth subculture’. This, perhaps, resonates with social work practitioners in Scotland who may be working within these communities.

Zick and colleagues (2009) also found that the less educated the participant, the more they hold general prejudices, stating that an educational system that emphasises democratic principles is crucial in reducing the likelihood of prejudice. In practice, there are many initiatives within Scottish schools to address prejudice-based bullying and hate crime (EHRC, 2017).

Socio-economic strain and perceptions of threat

Walters and colleagues (2016,p28) suggest ‘the perceived threat that certain groups of people pose to one’s own ingroup’ can lead to hate crime, such as perceived competition with ‘outgroups’ over employment, housing and other resources, particularly in socially and economically deprived communities. This resentment can then manifest in hate crime. Relatedly, grief and loss can be contributory factors. A small-scale study of people in Scottish prisons convicted of hate crime discovered that participants’ life circumstances at the time of the offence – including deteriorating health, loss of employment, housing and relationships – exacerbated by an inability to manage the resultant feelings and to problem-solve, contributed to the hate crime causation by scapegoating others (Penrice and colleagues, 2019).

Media and political rhetoric

Mass media and political influence can be crucial, with the sensationalist reporting of some events leading to ‘spikes’ in hate crime (eg following the EU Referendum and terrorist incidents). The media can actively create and perpetuate stereotypes about groups which influence individual consciousness, as well as the influence of far-right political parties and extremist groups (Roberts and colleagues, 2013), which have gained a concerning foothold in the UK and internationally. Indeed, a spike in hate crime was reported by police in England following a parliamentary debate on Brexit in September 2019 (Dearden, 2019).

Who commits hate crime?

Walters and colleagues (2016, p32) state that ‘there is no single ‘type’ of person who commits hate crime’, however, research draws attention to the commonalities in motivations and demographics. It is noted that the reviewed research is based on countries that have a white majority population and will, therefore, have limitations to generalisability.

Research suggests that perpetrators tend to be male, aged under 25 (although one study in London found the most common age to be 36), white, have previous involvement in the criminal justice system, are unemployed or in low-paid employment, and the hate offence often fuelled by substance use (Walters and Krasodomski, 2018; Iganski and Smith, 2011; Walters and colleagues, 2016). However, it is noted that individuals with previous convictions in general are more likely to come into contact with the criminal justice system than those who do not. Iganski and Smith (2011, p13) also caution that hate crime interventions cannot solely be premised on the notion of a ‘white racist offender’, and must be adaptable to the diverse characteristics of the people CJSW’s work with.

A typology

McDevitt and Levin developed a seminal ‘typology’ of people who commit hate crime in 1993, analysing 169 Boston Police Department hate crime case files and positing they could be classified into four categories:

- Thrill seeker (66%) – linked to peer dynamics and bored young males seeking excitement

- Defensive (25%) – motivated by a perceived threat from ‘outsiders’ and frequently linked to changing demographics in communities, which has implications when considering Scotland’s increasingly diverse population

- Retaliatory (8%) – motivated by situations where the ‘in-group’ has been attacked by the ‘out-group’ such as the aforementioned ‘trigger events’

- Mission (1 case) – motivated by ‘an ideology of hate’ and, therefore, more likely to perpetrate serious/fatal violence (Walters and colleagues, 2016, p36)

With the aforesaid increase in support for far-right ideologies, will the ‘Mission’ type of offence motivation be more apparent in the people CJSWs work with over time? The typology is also based only on hate crimes motivated by race/ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation, and as such, may have limitations in adequately accounting for disability hate crime, where exploitation may occur (Dodenhoff, 2016), or transgender hate crime.

‘What works’ in addressing offending?

Before considering what constitutes effective practice for hate crime, it is necessary to provide a brief overview of the current general approaches to assessing and supervising people with convictions in Scotland.

Risk-Need-Responsivity

The Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model is the predominant model of assessment and intervention with people with convictions (Bonta and Andrews, 2017), and it underpins Scotland’s CJSW services. This approach seeks to match the intensity of the service provided with the risk level of the case. It targets risks related to the offending behaviour and strives to develop these into strengths, using a variety of approaches tailored to the person. Practitioners must also seek to build respectful, collaborative relationships for successful interventions (ibid).

Desistance

Employing a purely RNR approach has been criticised due to the emphasis on risk, perhaps to the detriment of other needs (Bonta and Andrews, 2017). Therefore, desistance theory enhanced CJSW approaches in Scotland, with desistance describing ‘the process by which an offender ceases to engage in criminal behaviour’ (ibid, p341). The desistance process can involve maturation, gaining employment, forming a pro-social intimate relationship, gaining a sense of control or ‘agency’, and changes in the individual’s narratives/scripts and self-identity (ibid, p342). Developing a positive supervisory relationship is key to supporting this process of desistance. Anderson (2016) further advocates the concept of CJSW practitioners ‘bearing witness’ to people’s narratives and lived experiences to support the desistance process.

‘What works’ in addressing hate offending?

Must we do something different when working with people who commit hate crime? The lack of research in this area and scant evaluations of the very programmes designed to address hate crime, are quite apparent. Joliffe and Farrington (2019, p16) state that ‘…there is no robust evidence about ‘what works’ with hate crime offenders’ in the UK.

Risk assessment

There is also very little specific research on the risk assessment of people responsible for hate crime, yet Trickett (2019b) states ‘hate crime is a unique offence which needs specific and effective risk assessment tools’. Dixon and Court (2015, p382) propose certain dynamic risk factors, based on English probation service research and practitioner experience:

- A minimisation and denial of the aggravated element of the offending

- Blaming the victim and counter-accusations

- An absence of victim empathy

- A distorted sense of provocation

- Use of violence as a means of conflict resolution

- A poor sense of their own identity

- A sense of entitlement and alienation

- A distorted idea about the victim and perceived differences

- Perceptions of territorial invasion

- A distorted worldview

Criminal justice practitioners will observe that the majority of these factors may be present for the people they work with, with the latter five ostensibly linking more specifically to prejudice-based offences. Developing a risk assessment tool commensurate with the demographics and dynamics of people who commit hate crime in Scotland might, therefore, be important in shaping a tailored response to hate crime.

Hate crime interventions

Research exploring the key approaches for reducing non-criminal prejudice/bias (ie underlying attitudes/stereotypes) highlights positive, longer-term intergroup contact, (re)education strategies, diversity awareness courses, peer learning and media campaigns (McBride, 2015). When considering specific hate crime rehabilitation work, there is a consensus in the literature that there can be no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach due to the diverse causes/motivations of hate crime (Iganski and Smith, 2011). There are a number of criminal justice-based hate crime interventions across the UK, delivered variously by probation services and third sector organisations. In the Scottish context, the Anti-Discriminatory Awareness Practice Training (ADAPT) toolkit, a one-to-one cognitive behavioural-based hate crime intervention developed by the Grampian Regional Equality Council (GREC, 2013), remains widely available to practitioners across Scotland. SACRO’s STOP service is a Scottish Government-funded hate crime intervention (available only in North and South Lanarkshire, Glasgow and East Dunbartonshire).

Walters and colleagues (2016) provide an overview of the important elements of most hate crime interventions, such as: the incorporation of cultural/diversity awareness (without ‘preaching’); reflecting on attitudes and beliefs; anger/emotion management; and understanding the impact of hate crime on victims and communities. One-to-one work is viewed as more effective. Rehabilitative interventions should also involve work that serves to aid people’s reintegration back into the community, such as the development of employability skills. This, of course, already constitutes a significant part of the work undertaken by CJSW practitioners. Restorative justice (RJ) is also highlighted as part of empathy work.

The use of RJ – facilitating communication between those harmed by crime and those responsible for the harm – to address hate crime has gained increasing recognition. Indeed, the Independent Advisory Group (2016, p20) states ‘…the Scottish Government and partners should explore the use of restorative justice methods with victims and perpetrators of hate crime’. The Scottish Government published an RJ Action Plan earlier this year, and there are real opportunities for this to become part of the suite of responses within CJSW services to address hate crime given the existing knowledge, skills and approaches (Kirkwood and Hamad, 2019). Nonetheless, the use of RJ within statutory justice services for adults is not yet consistently available across Scotland.

Acceptance and relationship building

Lindsay and Danner (2008, p47) argue that, in the context of rehabilitative work, ‘...it is first necessary to accept oneself before one can accept other people’; an important point when considering the earlier points on shame and identity in people responsible for hate crime. McGhee (2007, p219) emphasises ‘…non-confrontational, non-demonizing engagement…’, however, acceptance does not entail the approval of, or collusion with, the person’s attitudes and behaviour. From practitioner experience and the desistance literature, it is clear that an accepting, non-judgemental, respectful relationship with the supervising officer is crucial and one within which change can occur.

While we may already work effectively with perpetrators of serious harm such as sexual abuse and domestic violence, Lindsay and Danner (2008, p44) propose that working with hate crime can pose additional challenges as ‘…it exists at one end of a spectrum of prejudice and oppression on which, if we are honest, we find ourselves’. As such, practitioners may assume a confrontational or challenging style with perpetrators, in order to assert a non-collusive stance.

This confrontational style with people who commit hate crime is unlikely to be successful in the absence of a ‘meaningful relationship between perpetrator and worker’ (ibid, p44). The fundamental role of the practitioner, therefore, is to facilitate a process that will lead the individual to confront their own attitudes and change behaviour. It is evident that the existing knowledge, skills, and values across CJSW services are robust foundations for working with those who commit hate crime, given the focus on relationship-based practice within the desistance journey, balanced with addressing risks and needs.

Dixon and Court (2015) add that relationship building in order to facilitate the exploration of prejudiced views, and promote a new narrative ‘script’, is vital. McGhee (2007) emphasises that practitioners must authentically engage in a dialogue with people who have committed hate offences and encourage them to discuss all aspects of their lives, including the hate offence and any prejudiced beliefs, and reflectively listen. In this way, discrepancies in people’s narratives can be ‘gently amplified’ and ultimately resolved via ongoing work (ibid, p219).

Implications for social work practice

Given the lack of evidence on ‘what works’ with hate crime, it might initially be difficult for practitioners to approach this work with confidence. Indeed, how do they even know they are accurately assessing risk in such cases, without a specific hate crime risk assessment? Developing a specific risk assessment tool, as has been done in English probation services, would be useful in the Scottish context. The author has done so for her local service based on the probation service’s research.

Using a one-to-one specialist Scottish hate crime intervention such as ADAPT, or being able to refer to local specialist services such as the STOP service, will take into account some of the different needs/risks for people who commit hate crime, however, the provision of this may be inconsistent across Scotland and might depend on local need, demographics and training. Any intervention should be adaptable and include components on the offender’s background and life experiences, victim awareness/victim empathy, conflict/anger management and emotional regulation, and components that are likely to be different from our general offending interventions. This might include cultural/diversity awareness (without ‘preaching’), and ‘myth-busting’ to address media rhetoric and stereotypes.

Where appropriate, an RJ element should be included. However, the provision of RJ across Scotland is variable, and CJSW services do not tend to work directly with the victims of crime. As such, the development of RJ across Scotland for statutory CJSW services, robust information-sharing protocols with key partners such as the police, and buy-in for RJ from senior managers at local levels, will be vital. Meanwhile, it will be useful for practitioners to undertake RJ training, and use RJ approaches in this work where possible.

It is important for practitioners to develop an understanding of the diverse causes and motivations of hate crime, and its impact, before embarking on any specific hate crime work. Given the majority of research focuses on men’s offending in this area, further consideration should be given to women’s pathways into hate crime. Further, if ‘communities of prejudice’ are important, can practitioners find creative ways in their localities of intervening at the family, peer group, and community levels? The core CJSW tasks of rehabilitation and addressing criminogenic needs will remain vital, such as engagement with other important areas of the person’s life eg employability, substance use and housing.

All of this work will be underpinned by the already robust knowledge, skills and values that defines CJSW in Scotland – relationship building, acceptance, a non-judgemental approach, and supporting the desistance journey. More specifically for hate crime, avoiding an overly-challenging, yet non-collusive approach, and allowing people to talk openly about their attitudes and prejudices, is important. Consequently, practitioners must be able to reflect on the work in supervision, and consider their own experiences (or lack thereof) of prejudice and discrimination.

References

- Anderson S (2016) The value of ‘bearing witness’ to desistance. Probation Journal, 63, 4, 408-424

- Awan I and Zempi I (2018) You all look the same: non-Muslim men who suffer Islamophobic hate crime in the post-Brexit era. European Journal of Criminology, 1-18.

- Bonta J and Andrews DA (2017) (6th edition) The psychology of criminal conduct. New York and Abingdon: Routledge

- Chakraborti N (2017) Responding to hate crime: escalating problems, continued failings. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 1-18.

- COPFS (Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service) (2019) Hate crime in Scotland 2018-19.

- Dearden L (2019) ‘Hate crime surged during Brexit ‘surrender’ bill debates in parliament, police reveal’. The Independent, 11 October 2019

- Dixon L and Court D (2015) Working with perpetrators. In Hall N, Corb A, Giannasi P et al (eds) (2015) The Routledge international handbook on hate crime. Abingdon: Routledge

- Dodenhoff P (2016) ‘How much do we really know about disability hate crime?’

- EHRC (2017) It is not cool to be cruel: prejudice-based bullying and harassment of children and young people in schools. Scottish Parliament: SP Paper 185

- Fletcher V (2019) Personal email communication with the author, 13 September.

- GREC (2013) Anti-discriminatory Awareness Practice Training (ADAPT). Aberdeen: Grampian Regional Equality Council

- Haider S (2016) The shooting in Orlando, terrorism or toxic masculinity (or both?). Men and Masculinities, 19, 5, 555-565

- Holland S and Scourfield JB (1999) Masculinity discourse in work with offenders. In Jokinen A, Juhila K and Pösö T (1999) Constructing social work practices. Aldershot: Ashgate

- Iganski P and Smith D (2011) Rehabilitation of hate crime offenders: research report. Scotland: Equality and Human Rights Commission

- Iganski P and Lagou S (2015) Hate crimes hurt some more than others: implications for the just sentencing of offenders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30, 10, 1696-1718

- Kirkwood S and Hamad R (2019) Restorative justice informed criminal justice social work and probation services. Probation Journal [OnlineFirst]

- Lindsay T and Danner S (2008) Accepting the unacceptable: the concept of acceptance in work with the perpetrators of hate crime. European Journal of Social Work, 11, 1, 43-56

- Lyons C (2006) Stigma or sympathy? Attributions of fault to hate crime victims and offenders. Social Psychology Quarterly, 69, 1, 39–59

- McBride M (2015) What works to reduce prejudice and discrimination? A review of the evidence. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- McDevitt J, Levin J and Bennet S (2002) Hate crime offenders: an expanded typology. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 2, 303-17

- McGhee D (2007) The challenge of working with racially motivated offenders: an exercise in ambivalence? Probation Journal, 54, 3, 213-226

- Penrice K, Birch P and McAlpine S (2019) Exploring hate crime amongst a cohort of Scottish prisoners: an exploratory study. Journal of Criminological Research, Policy, and Practice, 5, 1.

- Ray L, Smith D and Wastel L (2004) Shame, rage and racist violence. The British Journal of Criminology, 44, 3, 350-368

- Roberts C et al (2013) Understanding who commits hate crime and why they do it. Welsh Government Social Research Report No 38/2013

- Rohlfing S (2015) ‘Hate on the Internet’. In Hall N, Corb A, Giannasi P et al (eds) (2015) The Routledge international handbook on hate crime. Abingdon: Routledge

- Scottish Government (2015) Revised Prevent duty guidance: for Scotland

- Scottish Government (2016) Report of Independent Advisory Group on hate crime, prejudice and community cohesion (2016) report: Scottish Government

- Scottish Government (2017) Guidance for the delivery of restorative justice in Scotland.

- Scottish Government (2019a) Criminal proceedings in Scotland, 2017-18.

- Scottish Government (2019b) Consultation on Scottish hate crime legislation.

- Thompkins-Jones R (2017) Toxic masculinity is a macro social work issue. The New Social Worker, Summer 2017.

- Trickett L (2015a) Reflections on gendered masculine identities in targeted violence against ethnic minorities. In Hall N et al (eds) (2015) The Routledge international handbook on hate crime. Abingdon: Routledge

- Trickett L (2019b) Police forces offered valuable support with hate crime risk assessments following NTU research.

- Walters M, Brown R and Wiedlitzka S (2016) Causes and motivations of hate crime. Equality and Human Rights Commission research report 102.

- Walters M and Krasodomski-Jones A (2018) Patterns of hate crime: who, what, when and where? Sussex: University of Sussex and Demos.

- Zick A, Kupper B and Wolf H (2009) European conditions. Findings of a study on group-focused enmity in Europe. University of Bielefeld: Institute for Interdisciplinary Research on Conflict and Violence

Acknowledgements

This Insight was reviewed by Helen Allbutt and Kristi Long (NHS Education for Scotland), Sarah Davis (Community Intervention Team, City of Edinburgh Council), Paul Iganski (Lancaster University), Steve Kirkwood (University of Edinburgh), Maureen McBride (University of Glasgow), Neil Quinn (University of Strathclyde) and colleagues from Scottish Government. Comments represent the views of reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of their organisations. Iriss would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time to reflect and comment on this publication.