Introduction

Tools have the potential to transform how we work. Just like the DIY tools many of us keep in a cupboard at home, tools used in interactions between people have the power to save us time. They can also reduce effort, substantially increase the quality of our work, and aide and facilitate interactions and discussion between people. However, selecting the right tools and using them effectively is not easy; tools can end up sitting alongside creative engagement practice, rather than within it.

The use of tools in social service interactions can better support practitioners, reveal and reflect that which is unsaid, as well as the values, attitudes, constraints and assets practitioners bring to interactions

Winter 2009

This Iriss On… is the result of collaboration between Iriss and the Leapfrog project (a research project lead by Lancaster University in partnership with the Glasgow School of Art). The work of both Iriss and Leapfrog has revealed first-hand how people work together differently when they have a tool that gives them permission to engage with others in a different way. We’ve also found that people’s trust and confidence in using tools can vary; we sometimes need to encourage practitioners to give tools a ‘go’, and to better understand the effectiveness of their use in practice. Here we draw on this experience to take a closer look at tools, their role in creative engagement and the challenges that accompany using them.

Tools can be used to re-design and create new organisations, services and systems

Meroni & Sangiorgi, 2011

What do we mean by tools?

The term ‘tool’ is commonly used, interchangeably, with terms such as ‘resources’, ‘materials’ and ‘objects’. It is worth noting that ‘tools’ and ‘methods’ are also terms that are used interchangeably, however methods usually relate to a process in which a tool is used to assist people to reach a desired outcome.

Our Definition

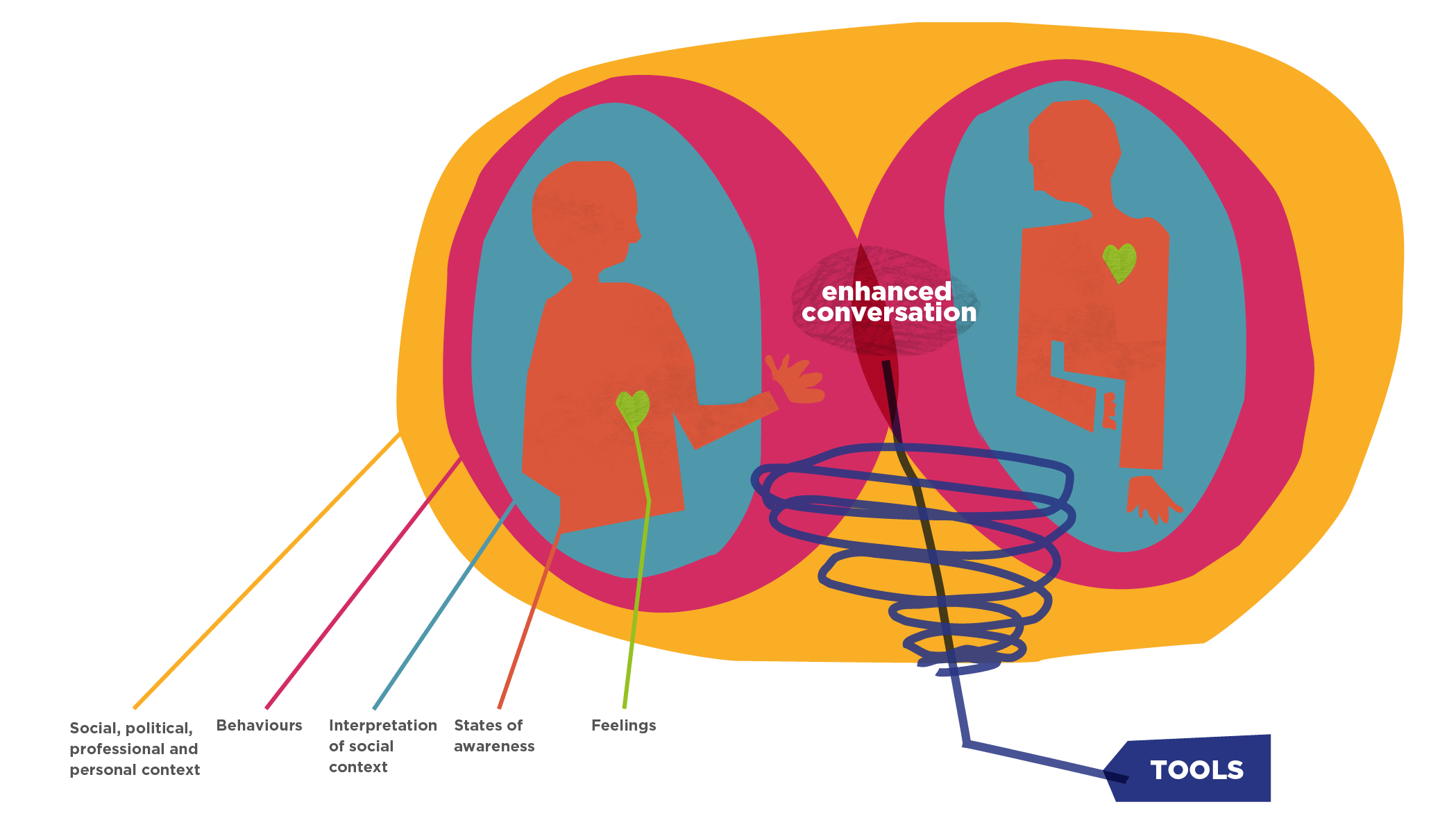

Tools are objects which aim to support people to perform a function or achieve a desired outcome that otherwise would be more difficult or even impossible. For example, a stone can be used to knock in a nail, but a hammer makes it safer, more accurate and involves less effort. Similarly, tools that enhance engagement in the social services can enable richer, more productive interactions between social service practitioners and the people they work with. Yet we believe the skills and experience developed by practitioners working in social services can be your most useful tool. So you yourself could be thought of as your ‘primary tool of practice’ 3.

Why tools can be useful

How people engage with one another is a very complex process. The process can be difficult to describe, relies upon people’s relationships with one another and how they communicate, and is influenced by aspects such as how they feel about one another, their roles and what they know and feel about the topic they are talking about.

However we’ll offer an interpretation to help get to grips with this process so we can highlight the contribution tools can make.

Interactions between practitioners and people who access services

There are, understandably, many approaches that social service practitioners may take when working with people. A core aspect of this role is using evidence from conversations and observations to make assessments about how they, in a professional capacity, can enable people. These judgements are made from several perspectives. They are influenced by organisational cultures and processes which invite and allow certain types of responses and not others, align with the profession’s code of ethics, and are influenced by the ability of the practitioner to relate to the person they are working with 4.

These judgements, are therefore, not neutral, which can complicate how practitioners and people who access support work together. From the supported person’s perspective, this experience can be further complicated, particularly when they experience crisis, are stressed, fearful or feel under threat (due to this interaction or for other reasons). Therefore, interactions can be highly emotional and intimate encounters. They may also not engage with the practitioner, or find it difficult to communicate their views, feelings and needs 5. Adding to this complexity are elements such as: the purpose of the interaction, what people’s needs are in any given situation, and how people prefer to communicate and learn.

In a health context, there is a broad framework which suggests the need for a ‘full range of activities’ that empower both the patient and the practitioner so that they have the knowledge they need to discuss particular topics 6,7.

Suggested activities include the:

- recognition and clarification of a problem

- identification of potential solutions

- appraisal of potential solutions

- selection of a course of action

- implementation of the chosen course of action

- evaluation of the solution adopted

These activities can include the use of tools. It is also thought that tools can better support practitioners, reveal and reflect that which is unsaid, as well as the values, attitudes, constraints and assets they bring to interactions with people who access services 8.

Designing services

Tools can also be an integral part of the re-design or innovation of organisational, service and system designs.

Meroni and Sangiorgi suggest that tools can be used to support people to analyse information, generate shared meaning, develop ideas and prototype new service ideas. When designing for services it is suggested that tools create a space in which people are given permission to engage with others in different ways, and encourage people to learn about one another, while acknowledging that neither person is an expert when it comes to the other’s knowledge and experience of the design of a service 9,10,11,12. Practical ways tools can support the way people work together include offering a means of mediating conversations 13, structuring the way people engage 14, and aiding memory and thinking processe 15. However, which tool, and when to use it, will depend on the needs of the people who are working together, the purpose and anticipated outcomes of any given situation.

Although not a comprehensive list of all the tools that can be used to design for service provision, Meroni and Sangiorgi 16 and Stickdorn and Schneider 17 present many service design tools and provide detailed explanations about their use in practice.

The right tool for the job

Navigating the myriad of tools available to social service practitioners is a daunting task for anyone. Our research reveals just how difficult it is to create a meaningful overview of tools because they are used in a extremely varied way in a great variety of contexts. Work within the Leapfrog project emphasises enabling adaptation of tools to fit with the needs and capabilities of specific individuals and groups.

In this section we present some of the tools that Iriss and Leapfrog have developed and describe how they can be adapted. We also signpost other tools that you may find helpful to enhance engagement.

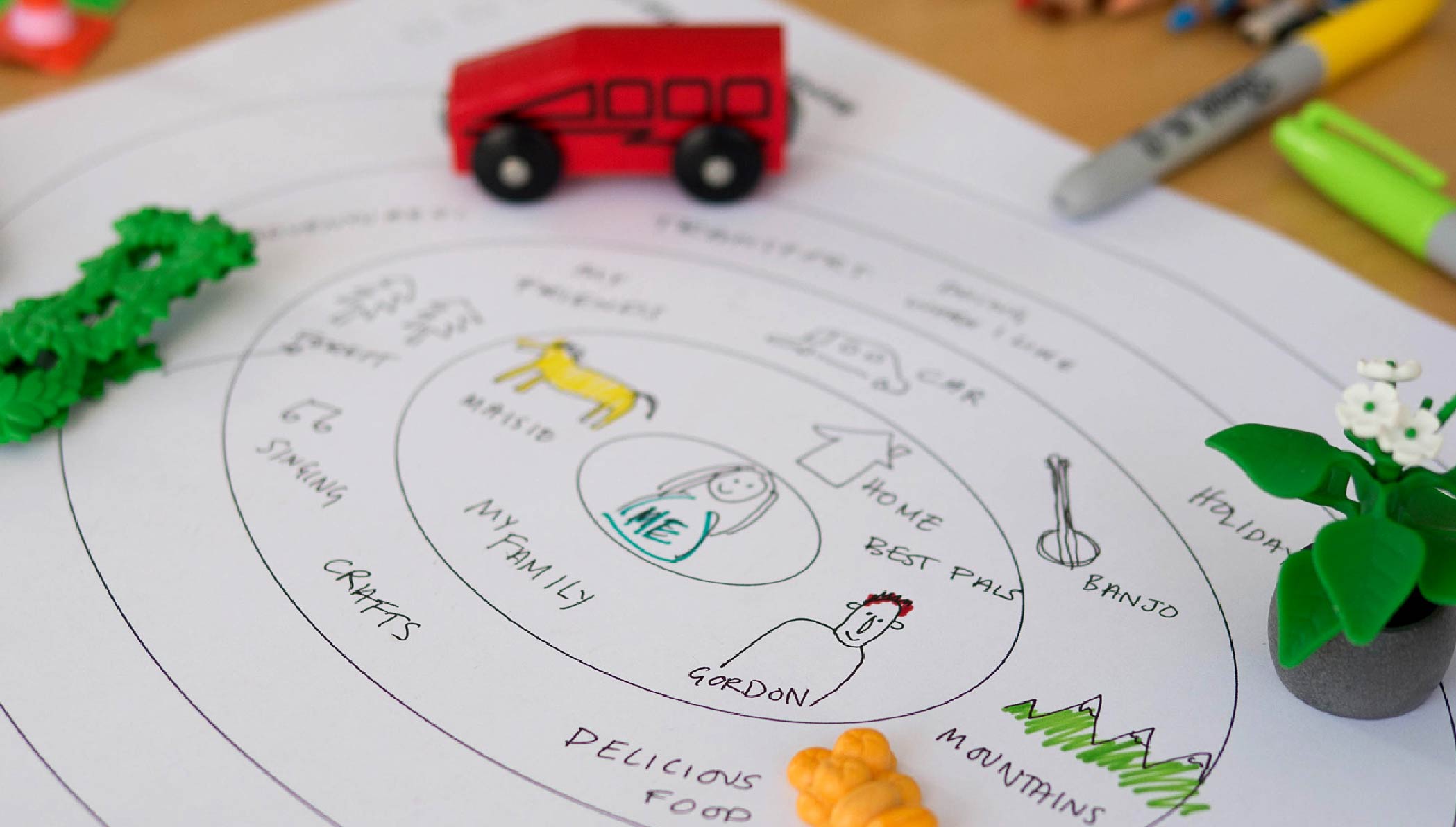

Tool name: What’s Important to You? (WITTY)

Type of activity: Engagement - reflection, personal assessment, planning

Intention and context: WITTY is an iPad app and paper-based tool which enables people to visually map positive assets and factors they have and can better engage with in day-to-day life. The intended outcome of using this tool is that people identify what it means for them to stay well, connected to these assets and happy.

This tool can be used to help people identify community and personal assets by creating a visual map of things a person has done in the past, things that exist in the present, or they would like to do in the future. This imagery enables people to see ‘the bigger picture’ of their life, and identify things they like and are able to do when they are not feeling well. It can be used individually, or to support conversations between practitioners and those who access support. If the tool is used with an asset-based approach it can also support conversations to move from a deficit-based model to an asset-based model when thinking about a person’s health.

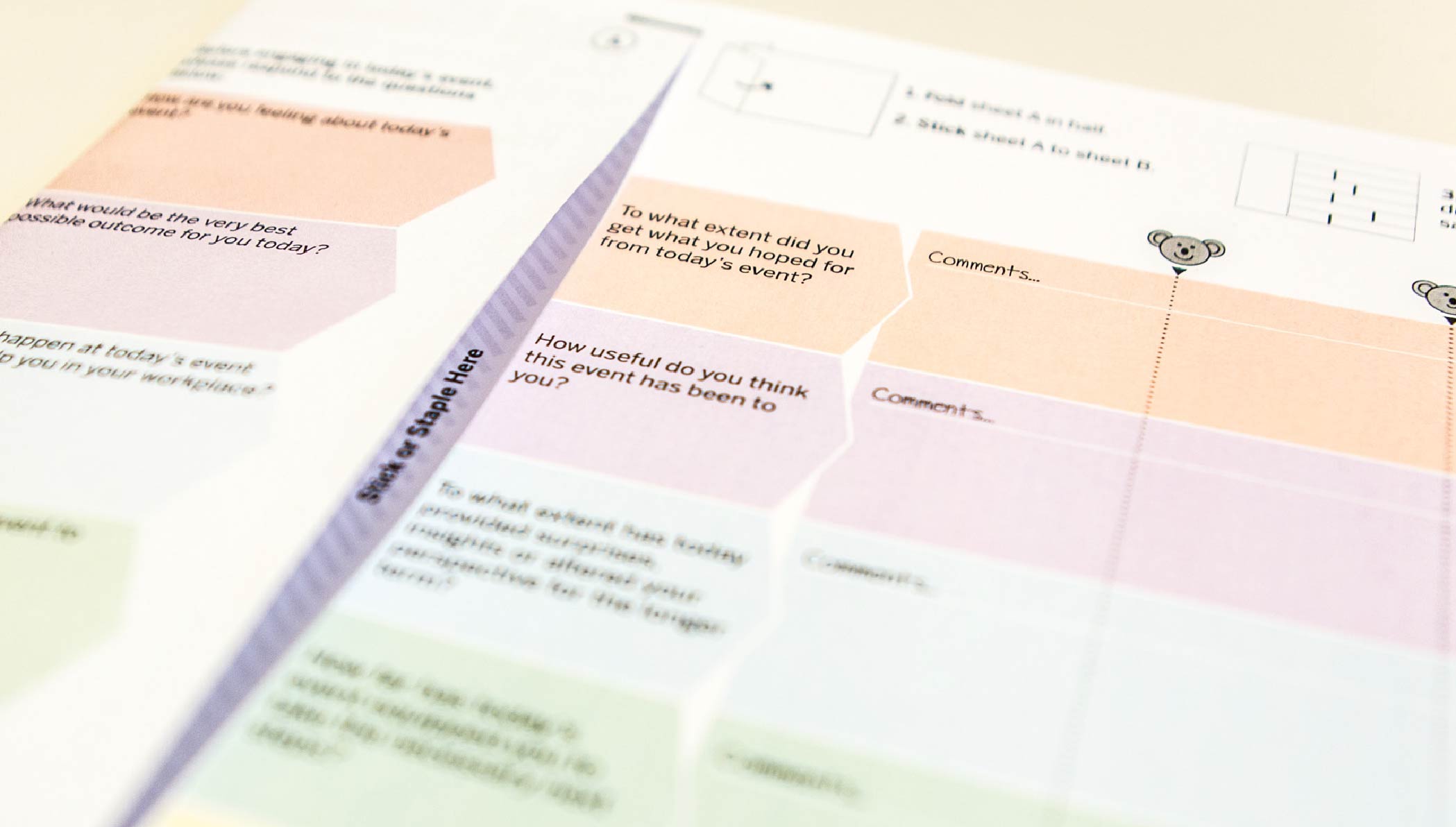

Tool name: Koala (KnOwledge And Learning evAluation)

Type of activity: Engagement evaluation

Intention and context: Koala seeks to improve end of a group work session evaluation by taking a different approach based on three principles.

- It captures expectations before an event and invites participants to use these as a baseline for reflection on the workshop.

- It invites the facilitator to tailor questions within the evaluation to better fit the needs and the audience they will be working with, rather than using generic language

- There is a constructional element to the evaluation, helping participants to see the evaluation as part of the workshop, as well as making it fun rather than just form-filling.

On or before arrival participants are invited to respond to a series of questions on an A5 sized sheet of paper. Critically, these are put aside and not available for participants to look at or modify during the session. At the end this A5 sheet is folded and wraps around or grips (like a Koala) an evaluation sheet that has a space for confidential comments, but also uses the expectations and other responses from the beginning of the session as a prompt for the evaluation questions.

We find that we get a great deal more qualitative feedback using this method compared to conventional evaluation sheets. We are also better able to calibrate these comments as we can better understand the starting or baseline state of the participant.

You may want to use this when thinking about developing service provision, or consider how to adapt it to use on a one-to-one basis.

Other tools that may enhance your practice

Participative practices can be key when enabling and enhancing working practices. You may, therefore, find several websites useful, such as:

- The Scottish Health Council’s Participation toolkit

- The Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design

- Helen Sanderson person centered practices

- The Inclusion Press person centered methods and tools

- In Control have a number of toolkits, presentations and templates to support inclusion

- Tools developed by Iriss to support people who access and provide services work together

- Leapfrog’s creative engagement consultation tools

There are lots of tools that people use to support the design of organisations and services. For example:

- Design methods for developing services

- IDEOs Human Centered Design and Prototyping Kit

- The Social Design Methods Menu

- Service Design Toolkits

- Innovation Tools

- Experience Based Design toolkits used to improve the NHS

- Other methods and tools to develop services

- A range of tools to support the design of services as highlighted by Meroni and Sangiorgi 16 and Stickdorn and Schneider 17.

There are also many tools that have been created to enable conversations that some people find difficult. For example:

- Helping children and young people communicate confidently: Conversation cards, Tools for social workers, In my shoes

- Supporting those with communication difficulties

- When working with complex systems

If you are aware of tools that are not included on this list please share a link to them using the #toolsforSSpractice on Twitter and include the Iriss and Leapfrog handle @irissorg @leapfrogtools so we can collate them.

Tips for adapting tools

Most tools are ripe for adaptation. If you do adapt tools, key tips include thinking about:

- Current and aspired outcomes and experiences of the interaction 18. Who should identify this?

- Capabilities of the people who will use the tool19. What support might be needed?

- Ability to capture a variety of perspectives in a way that is useful to those who are involved20. What methods can be used for this and how does this fit into existing processes?

- Impact of overarching cultural, social, political and relational conventions which can enable but also constrain interactions 21. Are these being challenged or accepted? How are they reflected in the design of the tool?

- Flexibility 22,23. How can the tool work with matters that may arise during conversations?

Of note, some creators of tools share them with the aim of contributing to a more equitable, accessible and innovative world. Free Creative Commons licensing is used to explicitly state under what circumstances tools can be used and adapted 24. This is something to check out when adapting someone else’s work.

Some benefits of using tools

It is important to point out that tools do not offer, structure, aid, prompt, encourage, reveal or reflect anything unless the people who are using them take the time to reflect on what they and others are hearing, seeing and doing. Reflective practice in the moment and after the event is key to making sense of what is learned individually and together 25,26,27,28. We would suggest that openly sharing what you are thinking, feeling and learning with others supports the engagement process.

If tools are fully integrated into practice then the outcomes of using them will be as unique as the contexts and situations they are applied in.

A tool may enhance or distract from your practice. It is hard to identify what makes a tool work well for everyone. Through the process of reflective practice you will be able to identify this for yourself. However, there is some emerging evidence that tools support:

Inclusivity

Fundamental to the use of creative approaches to engagement is the opportunity it affords to include all voices 29,30,31. Research into the partnerships between the voluntary arts and community sector, public and social service providers in the UK, provides evidence as to the value of creative engagement between public bodies and citizens.

Balancing power

There is a strong value associated with the ability of creative engagement to bridge divides. Tools that enable participation can support people to work together to co-create new practices, with improved chances of long term success 32,33.

Reflection

Gauntlett 34 identifies that when some people use tools they feel that they have been given time to create a thoughtful response to questions.

A holistic perspective

Using tools and developing visual imagery can aid people to develop opinions or responses on issues for which they do not always have words. As pictures are created, people are better able to discuss things from a holistic perspective rather than in the linear sequence, which language can often force. For example metaphors can be used to express abstract thoughts and feelings in a concrete way 35.

Creativity

Interestingly, tools and visual methods of engagement are said to support people to ‘unlock’ different kinds of responses, as the creative problem solving task means the brain works in a different way than when having a conversation without the use of tools 36.

Things to remember…

- Using tools reflectively with people can foster collaborative learning opportunities

- Taking time to acquaint yourself with the relative merits of different tools means that you will be ready to consider how you might adapt them to better serve you and others needs

- Some tools are easy to use when people are familiar with them, while other's require training

- Using tools can be an effective way to support people to engage with each other

- Good tools are not a substitute for good practice

Endnotes

- Iriss tools

- Leapfrog tools

- Ruch G, Turney D and Ward A (2010) Relationship-based social work, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Rice (2016) Developing an interdisciplinary approach to design for, and evidence, the outcomes of young people and leaving care workers’ experiences of conversations about leaving care

- Entwistle V and Watt I (2006) Patient involvement in treatment decision-making: The case for a broader conceptual framework, Patient education and counselling, 63, 263-273

- Winter K (2009) Relationships matter, Child and Family Social Work, 14, 450-460

- Bernstein B (1971) Class, codes, and control, Theoretical Studies Towards A Sociology of Language, London: Routledge

- Engeström Y, Engeström R and Kärkkäinen M (1995) Polycontextuality and boundary crossing in expert cognition: Learning and problem solving in complex work activities, Learning and Instruction, 5 (4), 319–336

- Star SL (1989) The structure of ill-structured solutions: Boundary objects and heterogenous distributed problem solving, In L Gasser and M Huhns eds. Distributed Arti cial Intelligence, 2, 37–54. London: Pitman

- Suchman L (1994) Working relations of technology production and use, Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 2 (1-2), 21–39

- Conole G (2008) The role of mediating artefacts in learning design, Handbook of Research on Learning Design and Learning Objects: Issues, Applications, and Technologies, 0, 188–208

- Conole G and Fill K (2005) A learning design toolkit to create pedagogically effective learning activities

- Norman, D. A. (1991). Cognitive artifacts, pp17-38, in J Carroll (ed), Designing interaction: Psychology at the human-computer interface, New York: Cambridge University Press

- Meroni A and Sangiorgi D (2011) Design for services, London: Gower Publishing

- Stickdorn M and Schneider J (2010) This is service design thinking, The Netherlands: BIS Publishers

- Jewett T and Kling R (1991) The dynamics of computerization in a social science research team: A case study of infrastructure, strategies, and skills, Social Science Computer Review, 9(2), 246– 275

- Bowker G and Star S(2005)How to infrastructure,pp230- 244, in L Lievrouw and S Livingstone (eds) Handbook of new media : social shaping and social consequences of ICTs, SAGE Publications Ltd: London

- Hasu M and Engeström Y (2000) Measurement in action: an activity- theoretical perspective on producer–user interaction, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 53(1), 61–89

- Ibid. 19

- Ibid

- Ibid. 18

- Creative Commons

- Dewey J (1916) Democracy and education, Philosophical Review, 735

- Freire P (2006) Pedagogy of the oppressed, New York: Continuum

- Forester J (1982) Planning in the face of power, Journal of the American Planning Association, 48(1), 67-80

- Sarkissian W, Hurford D and Wenman C (2010) Creative community planning, London: Routledge

- Ibid

- Kagan C and Duggan K (2011) Creating community cohesion, Social Policy and Society, 10 (03), 393-404

- Clennon O, Kagan C, Lawthom R and Swindells R (2015) Participation in community arts: Lessons from the inner-city

- Ibid. 30

- Ibid. 31

- GauntlettD(2008)Creative and refective production activities as a tool for social research, in J Prossor (ed.) ESRC research development initiative, building capacity in visual methods, Introduction to visual methods workshop [proceedings]. Unpublished

- Ibid

- Ibid

If you use tools as part of your practice share the tools you use with us by tweeting #toolsforSSpractice on Twitter and include the Iriss and Leapfrog handle @irissorg @leapfrogtools and tell us about your experiences.

To keep up-to-date with the work at Iriss please follow @irissorg on Twitter and sign up to the Iriss mailing list

To follow the work of the Leapfrog project, please follow @leapfrogtools on Twitter or visit the project website

- Written by: Gayle Rice, Leon Cruickshank, Roger Whitham and Hayley Alter. Thanks also extend to Lisa Pattoni and Rossendy Galabo for their contributions.

- Creative direction: Gayle Rice

- Illustration and Design: Josie Vallely

- Reviewed by: Debbie Lucas, Lead Officer, Child’s Plan, East Renfrewshire Council; Judith Midgley, Pilotlight Self Directed Support Associate, Iriss; Kathleen Quinn (MRes), Residential Foster Care Worker, Kibble.

The Leapfrog programme of work, undertaken by Imagination Lancaster and The Institute of Design Innovation at the Glasgow School of Art, is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. We would like to thank them for their contribution to the print costs of this publication.