- Understanding what an outcomes-focused approach means

- Identifying the different kinds of outcomes

- Recognising the differences between a service-led and outcomes-focused approach

- Understanding the benefits of an outcomes-focused approach

Outcomes in the context of integrated working

Outcomes are discussed fully in the parent guide (Leading for outcomes: a guide) and you may wish to refer to exercises 1 and 2 on pages 11-18 of that guide as an introduction to the outcome categories, the benefits of an outcomes-focused approach, and for an understanding of how this approach differs from a service-led approach. By outcomes we mean the impact of support on a person’s life, and not the outputs of services. Outcomes are the answer to the question: so what difference does it make? They are the changes or benefits for individuals whether as service users or informal/family carers.

In their work with Talking Points, Emma Miller and Ailsa Cook have developed the ‘cake analogy’ which has proved very useful in assisting with the understanding of outcomes (Cook and Miller, 2012). Imagine making a birthday cake for a child. The inputs are the ingredients (eggs, flour sugar); the process is the mixing and baking; the output is the cake. The desired outcome is a happy child. However there has to be discussion with the child to see if the outcome has indeed been successful: the child may have wanted a chocolate cake while you have made a fruit cake and the impact is to make the child unhappy, not a successful outcome!

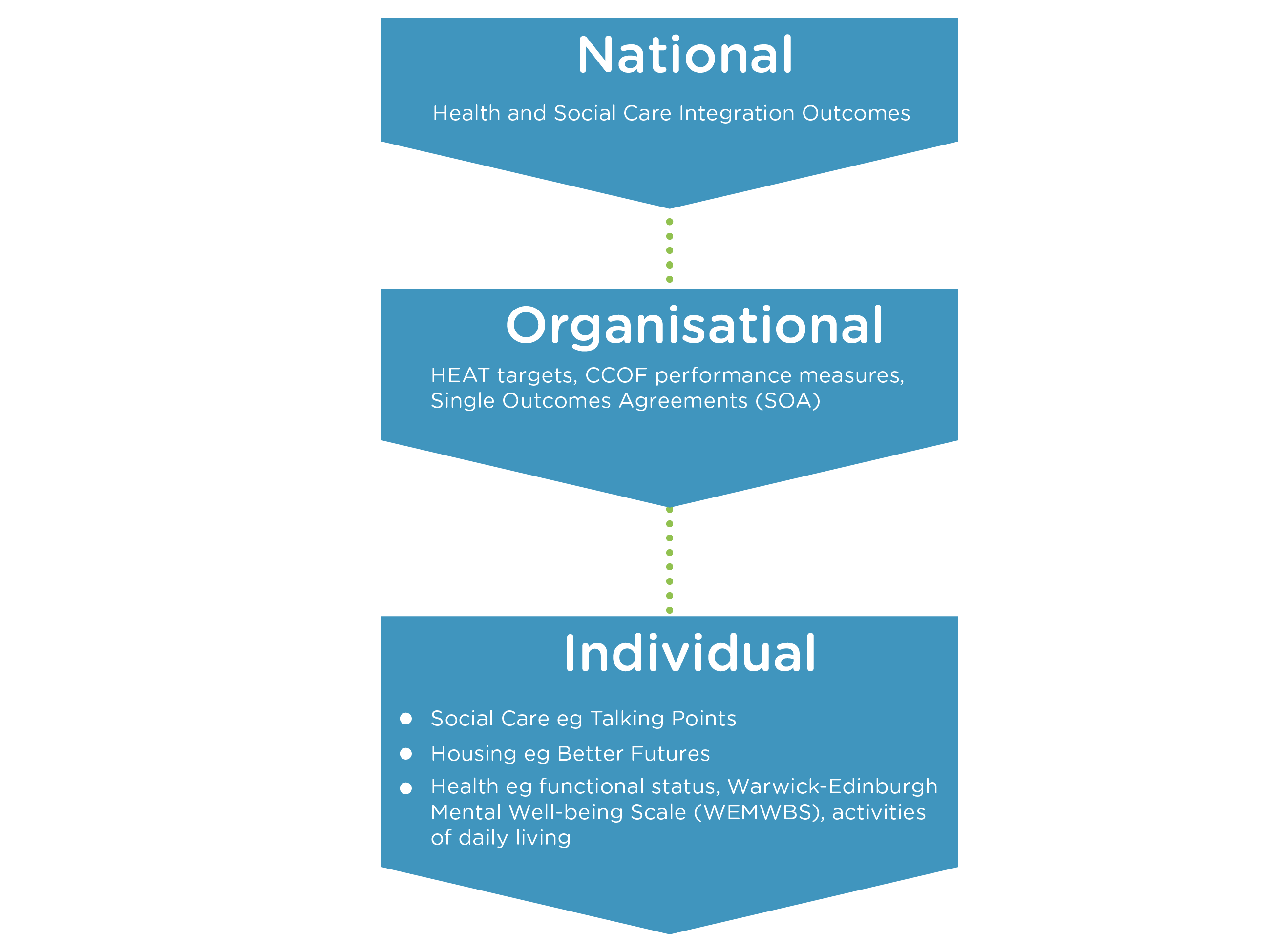

Your team may not be familiar with the term outcomes-focused, but may use related terms such as goals or person-centred planning. The terminology can be confusing and this needs to be acknowledged in your discussions with staff. ‘Outcome’ can be a vague term, susceptible to different interpretations that reflect different situational and disciplinary perspectives (Glendinning et al, 2007). Outcomes have often been interpreted as outcomes for services (such as a reduction in emergency hospital admissions or delayed discharges) and performance measures have focused on activity indicators, on inputs and processes, rather than outcomes for individuals.

The diagram below can be used to clarify the different levels at which the language of outcomes may be used. It is the personal level, the underpinning human experience, which is the concern of this guide.

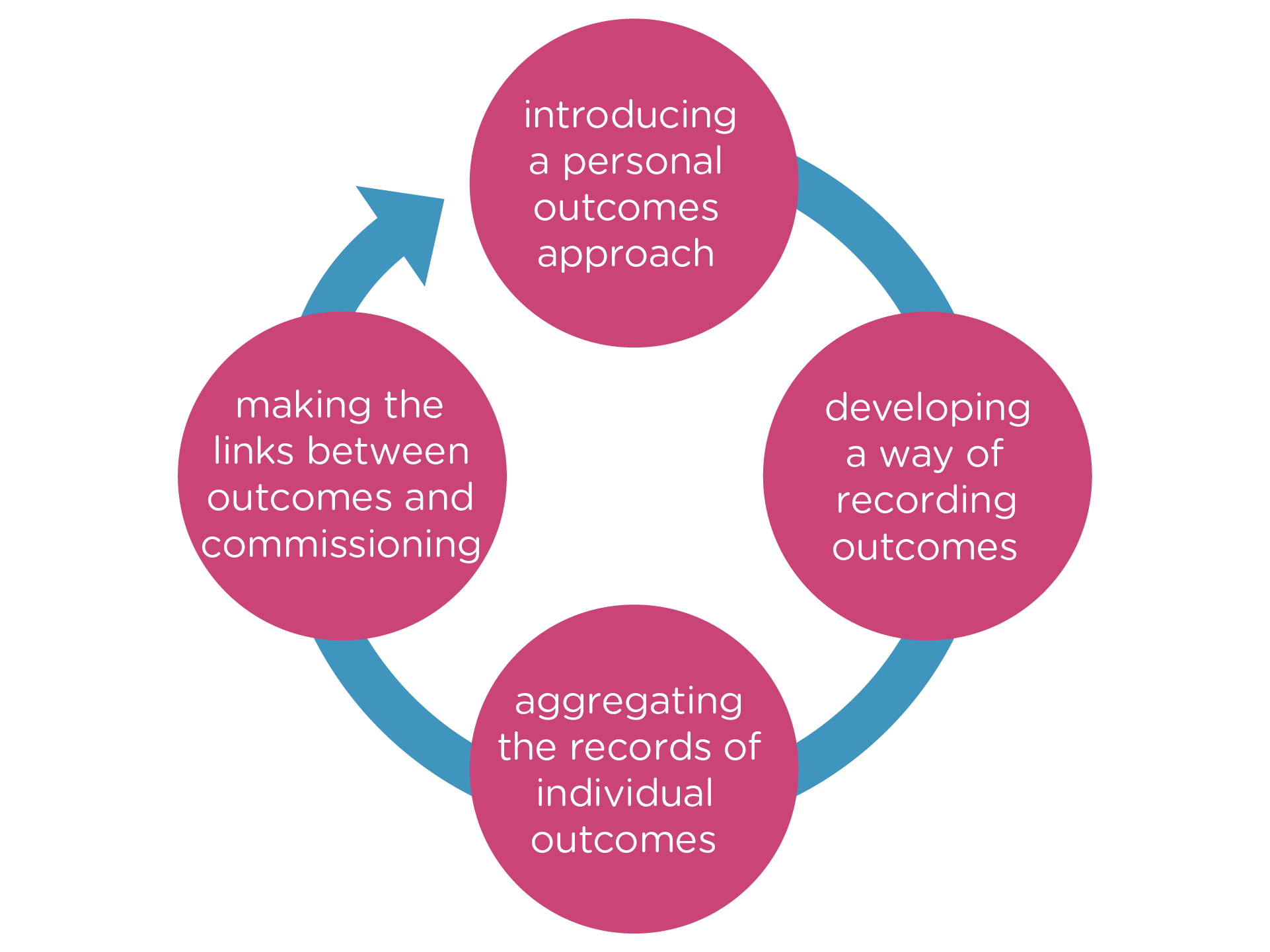

However it is important to recognise that ultimately outcomes at different levels should all feed into each other. This can be represented by the outcomes cycle displayed below. Introducing a personal outcomes approach requires a focus on outcomes-based assessment and review (Bennett et al, 2009). As part of this, teams need to decide how they are going to record outcomes. Attention should then be paid as to how the records of outcomes for individuals (achieved and not achieved) are to be aggregated. Finally the knowledge generated by this aggregation – resources that contribute to the achievement of outcomes, gaps in resources, investment that is ineffective – should be fed into the commissioning process and lead to outcomes-based commissioning.

In addition to the challenge of understanding an outcomes-focused approach, those from health care, from social care and from housing tend to interpret outcomes in different ways. This in turn reflects the traditional allegiance in health to the medical model and in social care to the social model. In terms of outcomes, this translates in health to a focus on aspects of presence or absence of specific symptoms and an emphasis on clinical indicators, generally in quantitative form. In social care, outcomes tend to focus on broader criteria, indicative for example of quality of life, and are often best captured through more qualitative measures. In part this is because much of social care supports maintenance of an acceptable lifestyle rather than necessarily expecting change.

As outlined in the parent guide, and further developed in the review by Netten (2011), there is a relatively strong evidence base relating to the outcomes that people who access support and their unpaid carers are looking for. Tables One and Two are reproduced from the parent guide and highlight the outcomes that are important to many people who use services and to their families and other unpaid carers. These derive from over a decade of research originating at the Social Policy Research Unit. Quality of life outcomes are outcomes that relate to daily living and support an acceptable life, for example being safe and living where you want. Process outcomes refer to the way in which individuals experience the delivery of support, for example feeling valued and respected. Change outcomes are outcomes that relate to improvements in physical, mental or emotional functioning, for example increased mobility or confidence or fewer symptoms of depression.

Table one: Outcomes important to people that receive support

Quality of Life |

Process |

Change |

| Feeling safe | Listened to | Improved confidence and morale |

| Having things to do | Having a say | Improved skills |

| Seeing people | Treated with respect | Improved mobility |

| Staying as well as you can | Responded to | Reduced symptoms |

| Living where you want / as you want | Reliability |

Table two: Outcomes important to unpaid / informal carers

Quality of life for cared for person |

Quality of life for the carers |

Managing the caring role |

Process |

| Quality of life for the cared for person | Maintaining health and well-being | Choices in caring, including the limits of caring | Valued/respected and expertise recognised |

| A life of their own | Feeling informed/ skilled/equipped | Having a say in services | |

| Positive relationship with the person cared for | Satisfaction in caring | Flexible and responsive to changing needs | |

| Positive relationship with practitioners | |||

| Accessible, available and free at the point of need |

Differing health and social care perspectives on outcomes

Many of the personal outcomes relating to social care focus on the achievement and maintenance of a good quality of life, for example feeling safe, having a degree of connection to family, friends and wider community appropriate to their wishes, having things to do, and feeling a sense of control.

Discussion of health outcomes refers to the impact that healthcare activities have on people – on their symptoms and on their ability in functional terms to complete certain tasks. Health outcomes primarily focus on whether a given condition gets better or worse, the impact of the condition and the results of the treatment that is given. Patient satisfaction may also be included as a dimension in discussion of health care outcomes. There is a wide range of validated scales used to assess functional status, including a swathe of measures focusing primarily on mental rather than physical health. The Scottish Schizophrenia Outcomes Study for example used the Health of the Nation Outcomes Scale (HoNOS) and the Avon Mental Health Measures (Avon). The EQ-5D is a generic instrument embracing the five dimensions of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. People are asked to record whether they have ‘no problems’, ‘some problems’ or ‘extreme problems’.

In terms of physical functioning, occupational therapists often have a role in ongoing measures of long-term health status. A common measure of functional status for example is Canadian Occupational Performance Measure.

A focus on activities of daily living (ADL) often encompasses both health and social care considerations, demonstrating the advantage of the multi-disciplinary perspective available in integrated working.

Since 2009 the NHS in England has introduced patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) for four surgical procedures (hip replacement, knee replacement, hernia and varicose veins) (Devlin and Appleby, 2010). Patients are asked to record their responses to a series of structured questions about their health according to their perspective before and after surgery.

Outcomes in housing

It is essential in integrated working to recognise that a prerequisite to the achievement of any health and social care outcomes is that the individual has adequate housing. Despite being one of the three pillars of community-based care it is still the case that housing is often overlooked.

The Better Futures outcomes tool is a web-based IT tool developed by the Housing Support Enabling Unit in Scotland and designed to look at the impact of housing support. It enables housing support service providers working with individuals to record their support needs over a period of time. It looks at five key areas: accommodation, health, safety and security, social and economic well-being, and employment and meaningful activity. Within each of the areas 20 elements of support are addressed. It provides a means of recording a baseline when someone starts using a service, as well as plotting their aspirations using an individual scoring system. The tool also allows for outcomes to be presented in the form of an outcomes star, demonstrating progress (or otherwise) over time. The tool addresses a number of different areas, with statements scored on a number of statements related to that issue. The following is an example of a section of the tool.

Extract from Better Futures Tool

Life skills

Description |

Level of support required |

|

4 |

|

3 |

|

2 |

|

1 |

|

0 |

Note: This part of the matrix aims to measure outcomes relating to life skills. Life skills are skills a person requires in order to live independently. These include shopping, cooking, cleaning, laundry, and personal hygiene.

The tools mentioned above are just a few of those that seek to record outcomes and can be used as part of an outcomes-focused approach. A collection of such tools and associated resources can be found in the outcomes toolbox. This includes for example a video explaining i-ROC (Individual Recovery Outcomes Counter), an outcomes tool developed by Penumbra. This is based on the four components of home, opportunity, people and empowerment (HOPE), with three elements in each of these areas. Another resource is the outcomes star developed by Triangle. Currently there are 15 versions of this tool embracing for example long-term conditions, homelessness, domestic violence, alcohol recovery, learning disabilities, and autism and Asperger's.

For an example which illustrates the broad distinction between different types of outcomes, consider initiatives designed to support older people more effectively in the community. Health outcomes may focus on a range of clinical measures of physical and/or mental health status and functioning for the individual, together with data on for example emergency admissions. Social care outcomes would tend to highlight whether for example the older person was able to achieve the things they wanted to do, whether they felt socially isolated and whether they felt satisfied with their contact with support staff. A consideration of housing outcomes would consider whether intervention is required in this area and if so whether the initiatives that are pursued are effective in terms of their impact.

Navigating the different meanings attached to outcomes in integrated working

It is essential that those involved in integrated working acknowledge the different understandings that those from different backgrounds may attach to outcomes. This can initially be challenging and in some situations where multiple agencies are involved there may be several competing or conflicting views involved in how to best achieve positive outcomes for an individual. Having an understanding of these potential differences of approach can help staff and teams (and service users and carers) to work together more productively.

The following exercise aims to develop a shared understanding about outcomes and an outcomes focus across health, housing and social services and amongst different professions.

Learning outcome

- Developing a shared understanding about outcomes and outcomes-focused practice across health, housing and social services and amongst different professions

Time

- No more than 60 minutes

Materials

- Post-its, flip chart

Guidance

- Ask the individuals in the group to write on post-its words that they consider refer to individual personal outcomes in their field. Stress that what you are looking for is the outcomes themselves, not some definition of the term; some groups may feel more comfortable at this stage with the term ‘goals’.

- Draw four columns on a sheet of flip chart paper. Head the first ‘input’, the second ‘activity’, the third ‘output’ and the fourth ‘outcome’. Read out each term and ask the group to decide if this is indeed an outcome for individuals who use services and/or carers, or if it refers to something else such as an input, or an output. Place the post-its in the appropriate column. Some of the terms may be about organisational outcomes rather than individual outcomes and these should be grouped separately along the bottom.

- Introduce the group to the cake analogy (see page 18) and to the classification of personal outcomes adopted by Talking Points (tables one and two on page 22).

- For each of the terms identified as an outcome, identify whether they are quality of life outcomes, process outcomes or change outcomes.

- Ask individuals to consider whether these outcomes are commonly identified in the course of their work with both users and carers and get them to explore if different professionals in their team place greater or lesser importance on each of these outcomes.

- Lead a discussion with your group about how integrated working can achieve a complete range of outcomes.