Key points

- Appreciative inquiry is an action research approach that offers a powerful contribution to meeting the appetite for real change that is evident across public services in Scotland.

- More mature understandings of appreciative inquiry, beyond a simplistic focus on positivity, can help to us to see old issues in new ways and offer fresh and welcome ways to challenge the status quo.

- Appreciative inquiry is both a personal and professional practice that has many applications across health and social care. This includes working with individuals or groups of people including staff and people that use services.

- This Insight provides some examples and highlights some of the practices, strengths and limitations of the approach.

Introduction

Many people are interested in how to promote innovation and change in health and social care. The need to pay greater attention to developing relationships, to work alongside people and communities, and to work in new partnerships are at the heart of many current policy ambitions and the case for public service reform (Christie Commission, 2011; Cottam, 2012; Audit Scotland, 2013; Wallace, 2013; GCPH and SCDC, 2015). Improving health and the quality of care, tackling health and social inequalities and promoting wellbeing for people and communities, demands a different approach that may feel at odds with parallel imperatives to save money and retain essential services.

Appreciative inquiry (AI) is part of the extended family of action research approaches. It is a developmental process rooted in the idea that our realities or social worlds are created by the language, interactions and relationships amongst us, including non-verbal communication and actions. AI relies on the idea that in every society, organisation, family or group, something works, at least some of the time. An appreciative approach aims to discover what gives life to a system, what energises people and what they most care about, to produce both shared knowledge and motivation for action. The deliberately affirmative assumptions of AI about people, organisations and relationships are a stark contrast to more traditional forms of research that seek to analyse or diagnose problems (Ludema, Cooperrider and Barrett, 2001).

There are clear links between AI and strengths-, asset- or solutions-focused approaches to health, social work, community development, workforce development, service design, coaching and leadership development. Yet, AI has often been narrowly understood as almost evangelically focusing on the positive and at times, dismissive of other approaches as deficit-orientated or problem solving (Dick, 2004). A better understanding of the offer of AI can contribute to meeting the appetite that is evident across public services in Scotland, for a way to work together to achieve real change. This Insight draws on the theory and practice of AI, focusing particularly on recent examples from health and social care in Scotland.

Asking the right questions

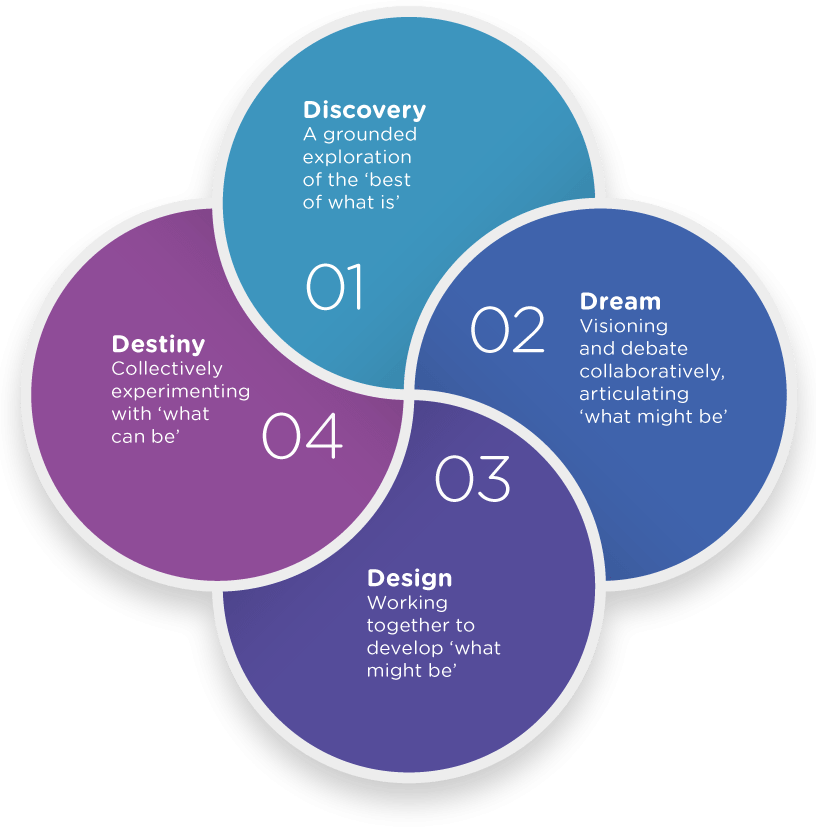

Many of us working in health and social care know how important it is to ask the right questions. If we focus on difficulties, people can feel hopeless and stuck, ourselves included. Asking about skills, successes or strengths, can acknowledge achievements and existing good practice, tap into enthusiasm and engender feelings of hope, even in some pretty difficult or desperate situations. The act of asking questions of a person, organisation, or group is an intervention that influences the situation in some way and ‘words create worlds’ (Hammond, 1998). There is no single AI method. AI is essentially a set of core principles that claim to change existing patterns of conversation and ways of relating, and give voice to new and diverse perspectives to expand what can be possible (Ludema, Cooperrider and Barrett, 2001). AI is usually described as using a four-stage version of the action research cycle, known as the ‘4D cycle’ and premised on the definition of a mutually agreed affirmative topic (Cooperrider and Whitney, 2000).1

Appreciative inquiry, transformational change and power

The claims of AI certainly deserve greater attention. Bushe and Kassam (2005) suggest that AI can be transformational where it focuses on changing how people think, instead of what they do and supports self-organising change processes that flow from new ideas. The primary principles are that inquiry starts with appreciation; the questions it addresses should be tested out in practice; it should be provocative and create new knowledge compelling to those involved; and it should be collaborative, involving system members in the design and execution of the inquiry (Bushe and Kassam, 2005).

AI is said to bring more equality in the researcher/participant relationship by making discussions more open and possible. In this way, it allows new voices to be heard and the action and knowledge produced be less skewed to the most powerful (Gaventa and Cornwell, 2001; Havens, Wood and Leeman, 2006). Asking people to describe dreams and wishes can often identify existing weaknesses (Mills, Bonner and Francis, 2006). Other authors are alert to the dangers that AI might ‘ignore the shadow’ of human experience, parts of ourselves or society that we may cover up or deny (Reason, 2000); be ‘too Pollyanna-ish’ or excessive focused on ‘warm, fuzzy group hugs’ (quoted in Grant and Humphries, 2006, p404).

A number of authors suggest that in complex situations of human dynamics and community power, AI can help to highlight issues of power, develop critical thinking and actions, disrupt self-limiting and taken for granted assumptions and be an ‘act of transgression’ that can change habits of deference (Grant and Humphries, 2006; Duncan and Ridley-Duff, 2014; Ridley-Duff and Duncan, 2015).

These finer tuned understandings suggest that AI can offer fresh and welcome ways to challenge the status quo. Purity of approach is not realistic given the complexities of real-world research and practice. It is not possible or desirable to corral people in a single type of response, whether positive or negative, or try to banish discussions of what people don’t like during AI, especially where there is a high emotional charge (Bushe, 2013). Rather, negativity can be explored by developing a sensitivity to multiple ways of seeing things, experiences and relations, while encouraging consideration of possibilities rather than dwelling on the problem. A few examples may help to illustrate the possibilities:

- In an AI study, Dewar (2011) found that adopting appreciative caring conversations to deliver compassionate care in nursing enabled people to feel comfortable to express emotions, develop stronger relationships, be more consistent in delivering compassionate care practice across teams, and develop a sense of learned hopefulness in the face of complex and competing demands.

- Duncan and Ridley-Duff (2014) used AI to work with marginalised Pakistani women living in Sheffield. They worked through many difficulties and dilemmas of AI and so empowered the participants to develop critical thinking, particularly around issues of power and identity: ‘Through generating authentic and untold stories, AI enabled participants to discuss, subvert and challenge the identities that had been constructed for them by sources of power within their community and culture.’ (Duncan and Ridley-Duff, 2014, p117)

- My Home Life (MHL)2 has found that AI works with and for people to change practice in a less threatening way, by focusing on what is currently working well and what more needs to be done to make it even better. It values all forms of knowing and crucially, includes connecting with and exploring what others value, respecting hidden stories of experience and personal narratives, and demonstrating a sensitivity to feelings. It supports change by establishing trust, authentic connection and a different quality of learning. An evaluation of the programme in Scotland 2013-15 found consistent results; it developed understanding of how to improve the culture of care, enhanced the engagement of staff and promoted greater leadership and communication skills, with positive outcomes for managers, staff and residents (Sharp and colleagues, in press).

Expanding appreciation: new ways of looking at old things

The recent ‘critical turn’ in AI expands notions of appreciation beyond the idea of positivity to include valuing more explicit forms of inquiry, building participants’ aspirations to design new social systems and acting in new ways to embed change (Ridley-Duff and Duncan, 2015).

In reviewing critiques of AI, Bushe (2013) suggests that positivity, particularly positive emotion, is not sufficient for transformational change, but that generativity is a key change lever. Generativity is the processes and capacities that help people see old things in new ways. This can be achieved through the creation of new phrases, images, metaphors and physical representations.3 In this respect, there is shared territory with design-thinking and approaches (Mulgan, 2014). These change how people think so that new options for decisions or actions become available, and are compelling, such that people want to act on them.

These two brief examples from care home managers show new ways of thinking about their role:4

“I used to feel like a one-man band and had to keep everything close, now I feel differently like conducting an orchestra. Empowering others and listening. Asking myself ‘what’s the worst thing that could possibly happen?’ It’s about moving forward and enjoying seeing others move forward with me.”

“I used to think I would want to care for people like I would want my own family member to be cared for. Now I know that this is not what I want to do. I want to care for people like they want to be cared for, which means I have to ask them. Everyone is an individual.”

The potency and emotional charge of these generative images and language can help to define affirmative topics, develop surprising questions that touch people’s hearts and spirit, and build relationships through sharing of stories (Bushe, 2013). Such generativity enhances capabilities and helps people to look at reality a little differently.

For researchers and practitioners, who aspire to work ‘as if people were human’ (Rowan, 2001), this stance offers a real-life-centric bias. Connecting with what others value, embracing the qualities of courage and fortitude and the acknowledgement of emotional pain can be the first steps towards creating authentic, caring and affirming connections between individuals (Sharp and Dewar, 2016, forthcoming). Focusing on creating space for inquiry, including exploring achievements and good practice, as well as difficulties, anger, injustice and despair, can contribute to a group’s ability to understand, and bring into being its collective aspirations.

Appreciative action research

The focus on ‘positivity’ has perhaps also neglected the collaborative and experimental dimensions of the action research cycle; the term appreciative action research can be used to emphasise this full cycle of inquiry that combines appreciation, discovery, envisioning, co-design and practical experimentation, with peer support and evaluation in a cyclical, dialogical and dynamic process (Egan and Lancaster, 2005; Dewar 2011; Dewar, Sharp and McBride, 2016).

Applications and practices of appreciative inquiry

Appreciative inquiry is both a personal and professional practice, with widespread applicability in contexts where more facilitative and collaborative cultures are desired. Used across the world in a great variety of contexts and situations, it can embrace small inter-personal exchanges, team, organisational, city or country-wide inquiries and whole-system change.5

McKeown, Fortune and Dupuis (2015) highlight that ‘it was one thing to learn about AI, but another to learn how to do AI’ (p8). This section highlights some of the applications and techniques that can be deployed. Building on Rowett (2015), applications most relevant to health and social care include:

- Practice development and care improvement

- Formative, summative and self-evaluation

- Customer, client or service user engagement, mediation, consultation and feedback processes

- Coaching, mentoring, staff and student supervisions

- Thematic reviews (for example, partnership working, customer service, IT systems)

- Recruitment, appraisal and talent management processes

- Continuing professional development (CPD)

- Service redesign and delivery

- Partnership development

- Community engagement and development

- Organisational and workforce development

- Person-centred planning and development of personal outcomes

A hallmark of AI is the nature of the questions asked together with the skills of conversational interviewing to avoid superficial social banter and cliché-ridden interaction (Bushe, 2013). Stories are also valuable as a way to develop rapport, trust and openness, place the person at the centre, develop a richer understanding of multiple realities, develop empathy and promote reflection and learning (Drumm, 2013). Fresh images and insight come from exploring the real stories people have about themselves and others, particularly when asked to consider them through an ‘appreciative lens’.

While asking people to recollect their most positive memories or stories remains important, there is much more to learn, especially in order to handle the complexities of positive and negative emotional expression in ways that are both authentic and safe. The ‘7Cs of Caring Conversations’ help to facilitate a more generative, appreciative dialogue (Dewar, 2011).6 This has been used in social care, community health, education, primary and acute care, where the focus has been on interactions amongst staff and others, facilitation of learning and relationship-centred practice. It is useful in action learning, user and carer involvement, clinical supervision, stakeholder meetings, story gathering and leadership programmes (Dewar and Sharp, 2013).

Insights into practices: developing appreciative, caring conversations

The My Home Life leadership support programme uses a model of Discover, Envision, Co-create and Embed similar to the original 4Ds. It uses Caring Conversations, a flexible practice framework to support practitioners to facilitate the development of generative, appreciative and relational capacities in care settings.7 This includes the ‘7Cs’ – seven attributes to promote appreciative caring conversations. Other tools that promote generative inquiry include the Positive Inquiry Tool, using images to explore feelings, and Emotional Touchpoints. Adaptability and playfulness are important aspects of this framework that build trust and relationships, as well as being a form of sense-making. The use of imagery, metaphor and stories help to deepen inquiry and enables people to say things that they may otherwise find intuitive, sensitive or awkward (Sharp and colleagues, in press).

Insights into practices: positive inquiry and feedback

Caring to Ask was a practice inquiry into Inequalities Sensitive Practice (ISP) in the north east sector of the Glasgow CHP, in collaboration with the Glasgow Centre for Population Health. This involved three teams of practitioners working in early years, homelessness and community mental health contexts, using the Caring Conversations framework with people accessing services, colleagues and partners. This helped set a tone of mutual interest and partnership and supported practitioners to craft good questions in the moment and elicit feedback.

“[M] asked a patient what was working well for him and he replied, ‘You asked me!’ When she asked what she could do to make things even better he replied, ‘Keep asking me!’”

“I had a young mother of 16 with very bad post-natal depression – she was being aggressive towards the baby, so there was social work involvement. It was hard for her to admit that she needed help. When I asked her, she said what had worked well was that I had not been judgemental – because of her age and inexperience. That I’d taken time to explain to her and her mother why social work were involved. I admit I was surprised that her feedback was positive…”

(Sharp and colleagues, 2013)

Insights into practices: discovering our future together

Animating Assets was a collaborative action research and learning programme that worked in four local areas in Glasgow and Edinburgh, during 2014-15. AI was built into the way that the meetings were run. For example, meetings would start with an appreciative icebreaker, such as asking people to share something they were pleased about in the community. In this way, it became easier to think about assets and what was valued, and ‘about how we build upon what was already there’.

Insights into practices: supporting health and social care integration

A small team from NHS Education for Scotland (NES) and the Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC) have worked with different partnerships across Scotland, using AI as a way of co-creating opportunities for workers across health and social care to be more directly involved in the planning and improvement of services. In Nithsdale, Dumfries and Galloway, the group focused on working as integrated teams, communication, early intervention and wrap-around care. They found that by using positive questions and being more focused on how they listen to each other, they came up with ideas and solutions that they weren’t expecting.8 This work has subsequently led to the development of an AI resource pack.

Principles of appreciative inquiry

Important principles of inquiring appreciatively, whether as an individual practitioner, group member or facilitator are to:

- Pay explicit attention to developing relationships and building trust and safety.

- Work with the principles of what works well, what is valued and what matters most to people.

- Adopt a facilitative and flexible approach that encourages participation, collaboration and experimentation.

- Enable ownership – which may mean revisiting taken-for-granted issues and prior assumptions, particularly around the definition of the focus of inquiry.

- Ask and encourage curious questions that are essentially non-judgmental to get to the heart of what is going on and remain curious.

- Don’t deny or dispute difficulties and negativity, but help people find what matters to them and reframe their thinking towards their hopes and possibilities.

- Make a commitment to real-time feedback to develop learning in a deliberate way.

- Use a variety of creative methods to promote dialogue, inclusion and sharing to build relationships as an explicit part of the process. These should include methods that develop different ways of knowing and types of evidence which enhance collaboration.

- Recognise and develop the relationships between staff and people that use services; support their carers and families with the issues they face.

- Encourage experimentation and adaptation to test out and get feedback which can be acted on to develop practical knowledge in and for practice.

- Allow the specific detail of the desired changes to emerge over time and in response to the local environment.

- Analyse and report on the processes of inquiry as an intervention for change.

- Support people to take local actions forward, evaluate these and share experiences across the wider organisation or community.9

Challenges

Like all change processes, AI will meet established ways of working, entrenched attitudes and cynicism and risks provoking defensiveness where experienced as an injunction. The specific hurdles for AI may stem from a sense that it is counter-intuitive, has been readily caricatured and needs to be nurtured and emergent rather than mandated or ‘rolled-out’. The theory-practice divide can also be a barrier; more hopefully, our own fuller engagement with the literature has provided useful insights to deepen and extend our own practice.

Conclusion

AI can make a powerful contribution to meeting the appetite for real change that is evident across public services in Scotland. It can help us to look at old things in new ways – ways that disrupt established patterns of thinking and interaction and move them in a positive direction. This fosters kindness and better relationships, enhances personal agency, promotes risk-taking and innovation, and engages more people in the design and testing of approaches to issues in the workplace and community. AI has widespread applicability and can be used at individual, team, organisational and system levels.

There are opportunities arising from the alignment with more established tools and approaches in health and social care and from the momentum for assets-based approaches that seek to recognise and build on strengths and existing good practice through mutual discovery (Garven, McLean and Pattoni, 2016).

References

- Audit Scotland (2013) Improving community planning in Scotland

- Bushe GR and Kassam AF (2005) When is appreciative inquiry transformational? A meta case analysis, The Journal of Applied Behavioural Science, 41(2), 161–181

- Bushe GR (2013) Generative process, generative outcome: The transformational potential of appreciative inquiry, in D.L. Cooperrider et al (eds) Organizational generativity: The appreciative inquiry summit and a scholarship of transformation (Advances in Appreciative Inquiry, Volume 4), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 89–113

- Christie Commission (2011) Commission on the future delivery of public services, Public Services Commission

- Cooperrider D and Whitney D (2000) A positive revolution in change: Appreciative inquiry, in Cooperrider, D et al (eds) Appreciative inquiry: rethinking human organization towards a positive theory of change, Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing LCC, 3–27

- Cottam H (2012) From relational ideas to relational action, in Cooke G and Muir R, The relational state how recognising the importance of human relationships could revolutionise the role of the state, IPPR

- Dewar B (2011) Caring about caring: An appreciative inquiry about compassionate relationship centred care, PhD thesis, Edinburgh Napier University

- Dewar B and Sharp C (2013) Appreciative dialogue for co-facilitation in action research and practice development, International Practice Development Journal 3 (2), [7], FoNS

- Dewar B, Sharp C and McBride (2016) Person-centred research, in McCormack B and McCance T, Person centred nursing theory and practice, 2nd edition, Wiley-Blackwell

- Dick B (2004) Action research literature themes and trends, Action Research 2 (4)

- Drumm, M (2013) The role of personal storytelling in practice, Iriss Insights, No 23, December

- Duncan G and Ridley-Duff RJ (2014) Appreciative inquiry as a method of transforming identity and power in Pakistani women, Action Research, 12 (2), June

- Egan TM and Lancaster CM (2005) Comparing appreciative inquiry to action research: OD practitioner perspectives, Organization Development Journal, 23 (2), 29–49

- Garven F, McLean J and Pattoni L (2016) Assets-based approaches: Their rise, role and reality, Dunedin

- Gaventa J and Cornwell A (2001) Power and knowledge, in Reason P and Bradbury H, Handbook of action research: participative inquiry and practice, London: Sage Publications, 70–80

- Glasgow Centre for Population Health and Scottish Centre for Community Development (2015) Positive conversations, meaningful change: Learning from animating assets

- Grant S and Humphries M (2006) Critical evaluation of appreciative inquiry: Bridging an apparent paradox, Action Research, 4(4), 401–418

- Hammond SA (1998) The thin book of appreciative inquiry, Thin Book Publishing, 2nd Edition

- Havens DS, Wood SO and Leeman J (2006) Improving nursing practice and patient care: Building capacity with appreciative inquiry, Journal of Nursing Administration. 36 (10), 463–470

- Ludema JD, Cooperrider DL and Barrett FJ (2001) Appreciative inquiry: The power of the unconditional positive question, in Reason P and Bradbury H (eds), Handbook of action research, Sage

- McKeown JKL, Fortune D and Dupuis SL (2015) “It’s like stepping into another world”: Exploring the possibilities of using appreciative participatory action research to guide culture change work in community and long-term care, Action Research, 0 (0), 1–17

- Mills J, Bonner A and Francis K (2006) Adopting a constructivist approach to grounded theory: implications for research design, International Journal of Nursing Practice. 12 (1), 8–13

- Mulgan G (2014) Design in public and social innovation what works and what could work better, NESTA

- Reason P (2000) Action research as spiritual practice

- Ridley-Duff and Duncan (2015) What is critical appreciation? Insights from studying the critical turn in an appreciative inquiry, Human Relations, pp1–21

- Rowett R (2015) Appreciative inquiry – Sustainable improvement through building on what works, AcademiWales

- Sharp C, Kennedy J, McKenzie I et al (2013) Caring to ask: How to embed caring conversations into practice across North East Glasgow

- Sharp C and Dewar B (2016, forthcoming) Learning in action: Extending our understanding of appreciative inquiry, in Zuber-Skerritt, O (ed) Learning conference in action: using participatory action learning and action research for sustainable development in a turbulent world, Emerald

- Sharp C, Dewar B, Barrie K et al (in press) How being appreciative creates change – Theory in practice from health and social care in Scotland, Action Research

- Wallace J (2013) The rise of the enabling state: A review of policy and evidence across the UK and Ireland, Carnegie UK Trust

Acknowledgements

This Insight was reviewed by Helen Allbutt (NHS Education for Scotland), David Formstone (East Dunbartonshire Council), Robin Jamieson (Scottish Community Development Centre), Ali Upton (Scottish Social Services Council) and colleagues from Scottish Government. Comments represent the views of reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of their organisations. Iriss would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time to reflect and comment on this Insight.

1 A ‘5D Cycle’ is sometimes referred to, that includes an extra ‘Define’ stage at the start, where the inquiry’s topic is developed and decisions are made about who should be involved.

3 This understanding of generativity is rooted in the work of Kenneth Gergen (1978) and Donald Schon (1979), rather than Erikson’s generativity stage of adult development (Bushe, 2013).

4 Taken from Dewar, 2011 and http://myhomelife.uws.ac.uk/scotland/positive-caring-practices/

6 The 7Cs are Be courageous, Connect emotionally, Be curious, Collaborate, Consider other perspectives, Compromise, Celebrate.

9 Adapted from Dewar, (2011)