Note: A subsequent development of Imagining the Future saw the creation in November 2014 of a scenario planning tool in which we explore four different worlds that might emerge depending on the interplay of social, political and economic factors.

Background

Over the next 10-15 years there are likely to be significant changes both in the numbers requiring access to support and in the strategies for responding to these needs. This project set out to:

- anticipate and detail the major changes and challenges in the context and environment within which the workforce will be operating and support will be negotiated

- explore a range of initiatives and potential developments which may facilitate responses to this future environment.

The expected outcomes were:

- Greater awareness of the challenges and drivers likely to operate over the next decade (end-point 2025).

- Awareness of a range of ideas and resources that can assist individuals and organisations in their planning.

- Willingness to respond creatively to the challenges presented and to embed a range of innovative responses.

Three key areas were identified for the preparation of 'think pieces': citizenship; workforce; and enabling technology. These areas of course are closely intertwined and although the three think pieces are presented separately their impact will be interdependent. It is hoped that the material presented here, together with associated resources, will provide the opportunity for widespread discussion and action over the next five to ten years.

There have of course been a number of recent 'futures exercises', some wide ranging, others more particular to health and social care. A few of these will be highlighted. One of the most comprehensive, based on 20 evidence reviews, is the Foresight Report on Future Identities (2013). This considers the emerging identities of individuals in the UK and the implications for policy, identifying in particular the development of 'hyper-connectivity' and the increased digital linking of public and private identities. The report highlights also increasing social plurality, influenced by the ageing population, changing patterns and greater diversity of immigration, and the emergence of 'virtual' communities. The implication of these emerging identities are considered for six key policy areas: crime prevention and criminal justice; health, environment and wellbeing; skills, employment and education; radicalization and extremism; social mobility; and social integration. Overall they conclude that:

Policy making across many different areas will need to be more iterative, adaptive, nuanced and agile, taking in to consideration the multifaceted nature of people's identities and how policies might affect different groups, or individuals, at different times and places. (p59)

A paper for the Carnegie Trust (Elvidge, 2013) focuses in particular on the potential role of the state in coming years. It introduces the concept of the Enabling State, suggesting a shift in the relationship between the state, communities and individuals. In summary it suggests:

The state has a vital future role in enabling the capacity of communities, families and individuals to grow wellbeing, in addition to maintaining an underpinning framework of excellent public services. This would require the state to mould itself around that capacity and respond to it, both in facilitating the growth of non-state capacity and in the way it organises the important continuing contribution of public services.

A review by Appleby for the King's Fund (2013) takes a long-term perspective and, as part of the Time to Think Differently programme, focuses specifically on the potential spending on health and social care over the next 50 years. Fifty years ago health and social care expenditure comprised 3.4% of GDP; currently the proportion is 8.2%. Continuation on a similar trajectory for the next 50 years would require a commitment of one fifth of GDP. The review explores the political and financial dimensions that need to be addressed.

Finally, and in some ways a precursor to the current report, the Dartington Review on the Future of Adult Care produced by Research in Practice for Adults (RiPfA, 2010) considered the future decade through the lens of three key areas: funding and welfare models from outwith the UK (Glendinning, 2010); the social care workforce (Bernard and Statham, 2010); and sustainability, including climate change and the fuel economy (Rae, 2010).

In this introduction to the current 'think pieces' the common context of demographic change is addressed and a number of other common features are highlighted.

Demographic Change

The demography of a nation is a complex construction of factors which are relatively uncontrolled. A major influence is life expectancy. This has increased for men in Scotland from 40 in 1900 to 76 today and is predicted to increase to around 79 by 2025. The increase for women over the same period is from 49 to 81 currently and x in 2025 [check]. Healthy life expectancy is increasing, but not at the same rate as life expectancy. Health inequalities in Scotland result in significant variation in mortality, life expectancy and healthy life expectancy across different areas, deprivation being a key determining factor.

The birth rate in Scotland has increased over recent years after a period of decline, although it is not clear if this will be maintained. The birth rate is, however, lower in Scotland than the rest of the UK, with women in Scotland delaying longer between births and more likely to stop at two children. The birth rate is lower in cities than in rural or commuter areas. The total fertility rate (1.77 in 2009) remains below the level required to maintain the population. Fertility is important as it contributes to population growth and profile and provides a longer-term solution than migration to maintaining the population. Fertility also has a bigger impact on the age profile of the country (and the dependency ratio in the longer term) than life expectancy. Currently the dependency ratio is 60 dependent to 100 people of working age; it is predicted to increase to 68 per 100 by 2033.

Immigration impacts on these figures. Scotland historically has been a country of net out-migration. In recent years this has been reversed as a result of both retention of the Scots-born population and increased in-migration. Scotland experienced a net migration gain of 27,000 in 2010-11, the highest since estimates began in 1951. The arrival of new families, generally of working age, will boost the dependency ratio over a number of years, especially as they are also of a reproductive age. The longer term picture regarding migration to and from Scotland remains uncertain.

In 2011 the population of Scotland was 5,254,800, an increase of 32,700 on the previous year and the highest ever recorded figure. The annual number of deaths in Scotland in 2009 (53,856) was the lowest ever recorded, with a focus on reducing mortality through tackling cancer, heart disease and stroke.

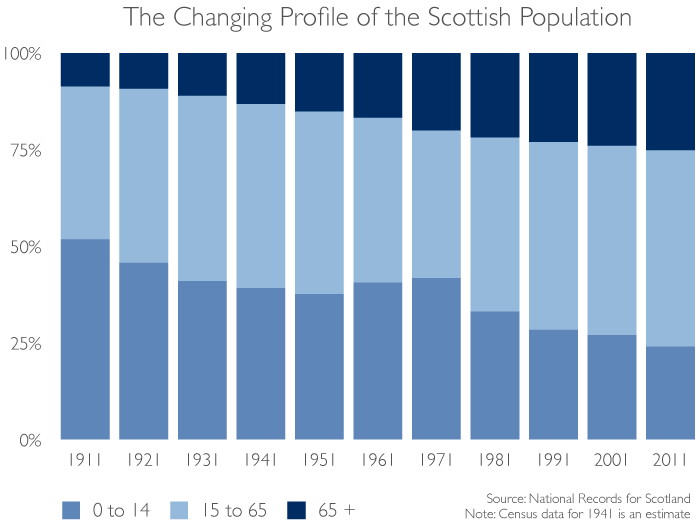

One of the most frequently expressed fears is that the 'ageing population' is in some way unsustainable and that it creates a significant resource problem. Figure 1 shows the changing percentage of the population in different age groups over the past 100 years. Between 2001 and 2011 there was a 15% increase in the number of people aged 75 and over. By 2033, a 50% increase in the over sixties and an 80% increase in those 75 and over is projected. Percentages of older people tend to be higher in rural areas.

Figure 1, demonstrates the changing population profile for Scotland. People are living longer and the rate of birth is falling. In fact the age profile is becoming more balanced. The numbers of people in the middle band (14-65), sometimes deemed to be 'productive' or non-dependent has grown slowly, while the number of children has fallen and the number of older people has grown.

Figure 1 Changing age profile of Scotland

However it is important to note that the implications of the ageing population are often over played. As argued by Appleby in his report for the King's Fund (2013): 'The ageing of the population is also a factor, although of much less importance than is generally supposed: increases in life expectancy tend simply to delay the time at which the health care costs associated with death are incurred rather than increasing these costs per se.'

Long term conditions

The majority of long term conditions cannot be cured but can be managed over extended periods of time through medication and changes in lifestyle. The more compliant a person is with dietary change, a need for more exercise and physical therapies, then the more successful is the overall treatment plan. Ultimately, this can extend life and certainly reduce the period of time spent with poor quality of life and disability due to the long term condition.

The most expensive long term conditions (in term of loss of Quality Adjusted Life Years) are:

- Coronary heart disease (CHD)

- Stroke

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Depression

- Lung cancer

- Diabetes

- Arthritis

- Colorectal cancer

- Asthma

- Kidney disease

- Oral diseases

- Osteoporosis

This list will change over the next decade as new pharmaceutical interventions target specific symptoms and help to overcome their impact on the lives of individuals. But these treatments will not be low cost and will stretch the budgets of the NHS, so some form of rationing may be necessary.

There is predicted to be a rise in multi-morbidity, the presence of two or more long term conditions. Although associated with ageing, this is not exclusive to the older age groups.

A study of 1.7 million people in Scotland registered with medical practices found rising numbers with multi-morbidity. Almost a quarter of all patients had multi-morbidity and more than half of those with a long term condition. Unsurprisingly, multi-morbidity increased substantially with age and was present in most people over 65. However while multi-morbidity is more prevalent in people 65 years or older, the absolute number with multi-morbidity was higher in those younger than 65.

The onset of multimorbidity also occurred 10-15 years earlier for people in the most deprived areas compared with the most affluent, with deprivation also associated with the prevalence of mental health disorders. Multi-morbidity is associated with high mortality, reduced functional status and increased use of both inpatient and ambulatory care. It is also characterised by complex interactions of co-existing diseases where a medical approach focused on a single disease does not suffice.

Dementia is a particular focus as the population ages. Currently there are estimated to be around 86,000 people in Scotland with dementia, a number that is expected to double over the next 25 years. Currently 60% live in the community and 40% in care homes or hospital. Arthritis Care believes that the number of cases of osteoarthritis is set to double to 17 million by 2030. The number of people with learning disabilities is expected to rise as their life expectancy increases and they grow into old age

Who will need social work services?

Some of the people who might need the support or advice of social work services include:

- Older people who are unable to perform some of the Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) or the instrumental activities such as using a telephone, managing money and travelling using public transport which are part of modern living

- Families who are unable to cope as a result of poverty or an inability of one or both parents to provide for children and to ensure that they receive regular schooling

- Children who are in care either on a permanent basis, perhaps after the loss of their parents, or on a temporary basis because their parents are in hospital or in prison

- Families with particular problems caused perhaps by the breakdown of a marriage or by antisocial behaviour exhibited by the children

- People who are disabled people as a result of physical limitations caused by accident, injury or a medical condition sometimes, but not always, present from birth

- People who are challenged by a sensory disability such as blindness, profound hearing loss or a combination of conditions

- People with learning or developmental disabilities that have special educational needs or who need support to live independently

- People who live with mental health problems that could be always present or which vary in their intensity over time

- Teenagers leaving care and who don't therefore have the parental support that might give them a head start over their peers

- Recently released prisoners who may have lost their close families and friends after being incarcerated for a number of years

- Those with a drug, alcohol or substance abuse problem which gives them permanent or temporary mental deficits and which challenges their ability to hold down a job

- Victims of social injustice generally and for whom society should be attempting to help in many ways

- Vulnerable adults facing physical and/or financial abuse sometimes from those that they used to love and trust

- People without capacity to give consent as a result of physical or mental challenges and for whom society must provide support which is in their interest

- Those who are socially excluded from society either as a result of past behaviour or through an inability to engage with officials in order to claim their rights

- A new generation of digitally excluded people who are not able to access or perhaps not willing to accept the requirements of 21st Century life.

The above list in long but not complete as there are likely to be other groups of people who will appear, perhaps as social injustices increase and they are excluded from mainstream job opportunities and welfare payments. Nevertheless, the list provides a means of testing propositions, including the case study examples provided in the appendix.

References

- Appleby J (2013) Spending on health and social care over the next 50 years - Why think long term? London: The King's Fund

- Elvidge J (2012) The Enabling State: A discussion paper, Dunfermline: Carnegie UK

- Foresight Future Identities (2013) Final Project Report, London: Government Office for Science

- RiPfA (2010) Dartington review on the future of adult social care, Dartington: Research in Practice for Adults, comprising:

- Humphries R (2010) Overview report

- Glendinning C (2010) What can England learn from the experiences of other countries? Evidence Review One

- Bernard J and Statham D (2010) The future adult social care workforce, Evidence Review Two

- Rae J (2010) Personalisation, sustainability and adult social care: strengthening resilient communities, Evidence Review Three