Key points

- There have been significant developments in joint investigative interviewing practice in Scotland

- The provision of non-suggestive social support is key to a child’s experience of the joint investigative interview and the quality of evidence and information secured

- Current joint investigative interview training and practice stresses the importance of the application of trauma-informed principles and the provision of non-suggestive social support during joint investigative interviews

What is a joint investigative interview?

A joint investigative interview is undertaken by a police officer and social worker. The Scottish Government (2011) defines an investigative interview as:

…a formal, planned interview with a child, carried out by staff trained and competent to conduct it, for the purposes of eliciting the child’s account of events (if any) which require investigation.

The national guidance for child protection in Scotland (Scottish Government, 2021) states that the purpose of an investigative interview is to:

- Learn the child’s account of the circumstances that prompted the enquiry

- Gather information to permit decision-making on whether the child in question, or any other child, is in need of protection

- Gather sufficient evidence to suggest whether a crime may have been committed against the child or anyone else

- Secure best evidence as needed for court proceedings, such as a criminal trial or a children’s hearing proof

Previous joint investigative interview practice in Scotland

Between 2011 and 2017, studies undertaken in relation to joint investigative interviewing practice in Scotland found that interviewers did not follow recommended guidance or adopt appropriate questioning strategies.

La Rooy, Lamb and Memon (2011) found that despite being confident in their practice, interviewers did not always follow the guidance. Waterhouse and colleagues (2016) found that interviewers demonstrated a reliance on option posing or suggestive questions, at odds with practice guidance, but again in line with the findings of previous research (La Rooy and colleagues, 2012; La Rooy, Earhart and Nicol, 2013).

The need for change

In March 2015 The Evidence and Procedure Review (2015) recommended that:

… consideration is urgently given to the development of a new, structured scheme that treats child and vulnerable witnesses in an entirely different way, away from the court setting altogether...There must be sufficient investment in the quality of interviewing, questioning, and examination applying the highest international standards and requiring appropriate training and qualification (p37).

Following on from this initial report and the Evidence and Procedure Review Next Steps Report (2016), in June 2017 the Joint Investigative Interviews Work-stream Project Report made 33 recommendations to improve the quality of joint investigative interviews. One of the recommendations was to ensure the training for interviewers reflected the highly specialist skills that are required for this task:

The training programme for joint investigative interviewers should be developed and extended to enable more in depth training of interviewers, recognising the degree of specialist skill required to secure best evidence.1

As a result of these recommendations the National Joint Investigative Interviewing Project was established in 2017. Experienced practitioners and managers from police and social work were recruited, with the primary remit of drawing on national and international research and best practice, to create a model for joint investigative interviewing tailored to the Scottish context.

Messages from research – non-suggestive social support

What do we know about offering support to children, while avoiding option posing, suggestive or leading questions? When developing the new model of practice, the team recognised the importance of taking the impact of experiences of trauma and adversity on a child’s ability to participate in an interview into consideration, as well as incorporating learning from research on the provision of non-suggestive support in the interview. This is explored below before going on to describe the model in more detail.

It is important to be clear on what is meant by social support. Saywitz and colleagues (2019) helpfully summarise previous definitions:

In the interview context, Davis and Bottoms (2002) suggest defining interviewer support ‘as a form of social interaction or communication that fosters a feeling of well-being in the target’ (p186). In research studies, elements of supportive interviewer behavior [sic] have been operationalized as provision of warmth, smiling, friendliness, eye contact, interest, open-body posture, positive feedback, using the interviewee’s first name, and so forth (e.g., Davis and Bottoms, 2002; Goodman, Bottoms, Schwartz-Kenney, and Rudy,1991; Quas, Bauer, and Boyce, 2004).

There are several factors which can impact on a child’s ability to recall their experiences within the context of the joint investigative interview. If they do not fully understand what has happened or if they were not paying sufficient attention to an event, it may not be recorded in their memory in a way that enables subsequent disclosure. It might be that they are unable to recall sufficient detail about the event or that they lack the capacity to communicate it.

There might be motivational factors that make it difficult for them to talk about what has happened, such as ‘embarrassment, fear, and anticipated negative consequences’ as described by Hershkowitz and colleagues (2017). There is other research, outwith the scope of this Insight, which more fully explores the motivational factors that may make a child more reluctant to provide an account of their experiences in a forensic interview. Children find it more difficult to disclose abuse perpetrated by a close family member, particularly parents or carers. Research also suggests that it is more likely that an initial disclosure will be delayed and made to a person outside the family if abuse is perpetrated by a close family member.

Younger children are even less likely to report abuse perpetrated by a close family member. Pipe and colleagues (2007) reported that only 38% of the pre-school aged children reported sexual abuse perpetrated by a parent, even when independently corroborated. The research also suggests that boys may be more reluctant than girls.

Fear of family rejection and disbelief impact on the child. Parental, particularly maternal, support following initial disclosure is important for a child’s ongoing emotional wellbeing. Some research suggests that parental responses can be impacted by their own distress. However, ‘expectations of negative reactions were strongly associated with delayed, non-spontaneous, and indirect disclosure to a non-parent figure’ (Lamb and colleagues, 2008). Children who expect negative parental reactions are often accurate in their expectations. It is also suggested that there is a relationship between children expressing concern about parental response and either fully or partially recanting their allegations at a later date.

Children with ‘impaired functioning’ have been found to be less likely to make allegations of abuse (Hershkowitz, Lamb and Horowitz, 2008). They are likely to be more dependent on their caregivers, potentially more vulnerable to abuse and less able to talk about it. They are also less likely to be interviewed.

It is important to consider the impact of other factors too. Hershkowitz and colleagues (2005, 2007) found that school aged children were more likely to disclose sexual rather than physical abuse. Lamb and colleagues (2018) note the importance of taking account of a child’s disclosure history – if a child has already spoken about their experiences, they may be less reluctant to participate in interview (p163).

A lot of research tells us the importance of offering children and young people non-suggestive social support in the context of the forensic interview. Offering children non-suggestive social support during forensic interviews may not only promote their sense of well-being but also enhance the richness and accuracy of their testimony’ (Hershkowitz and colleagues, 2017).

Trauma and adversity can affect children and their general development; affect their ability to make sense of, store, and remember events; affect their ways of coping and managing feelings under pressure; affect a child’s understanding of relationships and people, which might affect how and who they tell. If interviewers can create an environment where the child feels safe, understood and calm this can help them talk about their experiences within the forensic interview setting.

The new model of practice for joint investigative interviews in Scotland seeks to provide interviewers with the skills to attune to the needs of the child in interview, supporting the child to be as regulated as possible and minimise the risk of further traumatisation.

This requires the interviewers to apply the trauma-informed principles of safety, choice, collaboration, trust and empowerment to their planning and practice within the interview. Examples of how this can be applied to the interview are listed below:

Safety

Interviewers must consider known or potential triggers and set up the environment in a way that promotes the child feeling physically and emotionally safe.

Choice

The child is offered choices, such as where they sit, who accompanies them, who they speak to, and how they will signal that they need a break.

Collaboration

It is important that interviewers avoid jargon, make appropriate use of eye contact, maintain a warm even tone throughout the interview and demonstrate active listening. Interviewers must take the child seriously and remain respectful. Where appropriate the child will be involved in planning for the interview and identify what they want to do during breaks.

Trust

To build a trusting relationship with the child, interviewers must be clear about their role and the purpose of the interview. If the child asks questions, they must be honest about things they don’t know or requests they are not able to action.

Empowerment

Interviewers must empower the child by acknowledging and including their strengths and interests, going at their pace and being realistic about their capabilities.

Interviewers must pay heed to the child’s non-verbal communication in the interview to support the child to remain regulated and able to engage – they must attune to changes in the child’s physical presentation and mood and consider what this might be communicating about their ability to manage their emotions throughout the interview.

Katz and colleagues (2012) reviewed forty NICHD Protocol2 interviews of children aged between three and thirteen years old, for which there was independent evidence of abuse. They found that the children who did not talk about their experiences, but exhibited ‘more non verbal indicators of physical disengagement’, such as looking away, hiding their face, or leaving their seat. This supports the importance of interviewers remaining attuned to the child’s needs and helping their engagement in the interview.

By recognising and responding to the needs of the child, interviewers can create an optimal environment for the child to talk about their experiences. This approach is likely to reduce stress and help the child to stay emotionally regulated. It is also likely to support the child’s recovery by minimising the risk of further traumatisation and helps the interviewer to undertake the interview to the best of their abilities.

Saywitz and colleagues (2019), when considering the effects of interviewer support on children’s memory and suggestibility, summarised the messages from research very clearly:

Often, the forensic interview is a child’s first point of contact with the legal, social service, or mental health systems. There is no doubt that such interviews must be conducted in ways that avoid distorting children’s reports and creating false accusations. However, the available research suggests that supportive interviewers will provide higher quality evidence to decision makers than neutral or nonsupportive interviewers. This is especially important because studies suggest jurors are more skeptical [sic] of children’s reports when provided in more socially supportive contexts (Bottoms and colleagues., 2007).

Even though interviewers are temporary figures in children’s lives, they are present at pivotal moments. The effect of a positive interview experience, where children feel they have been treated as respected, competent sources of important information, may have profound consequences, affecting their attitudes toward the system, themselves, and their adjustment to case outcomes. Failing to respond to children’s statements about abuse or violence in a supportive manner may constitute a missed chance for positive effect at a critical window of opportunity.

A new model of practice

It was clear to the project team that the new model of practice needed to incorporate a rights-based, trauma-informed approach to forensic interviewing of children. To help ensure that trauma-informed principles underpin forensic interviews of children in Scotland, the team engaged Dr Caroline Bruce and Dr Nina Koruth from NHS Education Scotland, who have been central to the development of the National Trauma Framework.

The team liaised with speech and language therapists to ensure that the training programme provided interviewers with the skills to respond to the speech, language and communication needs of children during the joint investigative interview.

The team reviewed the research and evidence underpinning different interview protocols and concluded that the interview protocol to be adopted in Scotland would be the Scottish NICHD Protocol. The NICHD Protocol was first developed in the 1990s and is the product of an interdisciplinary team that included researchers, forensic interviewers, police officers and legal professionals who were seeking an evidenced-based approach to forensic interviewing. The protocol has been subject to intensive research and scrutiny ever since. The Scottish NICHD Protocol is based upon the Revised NICHD Protocol, which has been further developed based on ongoing research to allow for the provision of further non-suggestive support.

The project team has benefitted from the support of Professor Michael Lamb and Dr David La Rooy to develop the Scottish NICHD Protocol.. Professor Lamb was involved in the original development of the NICHD Protocol and has continued to contribute to the ongoing body of research. As has Dr La Rooy, who undertook significant research on previous interview practice when he was based in Scotland.

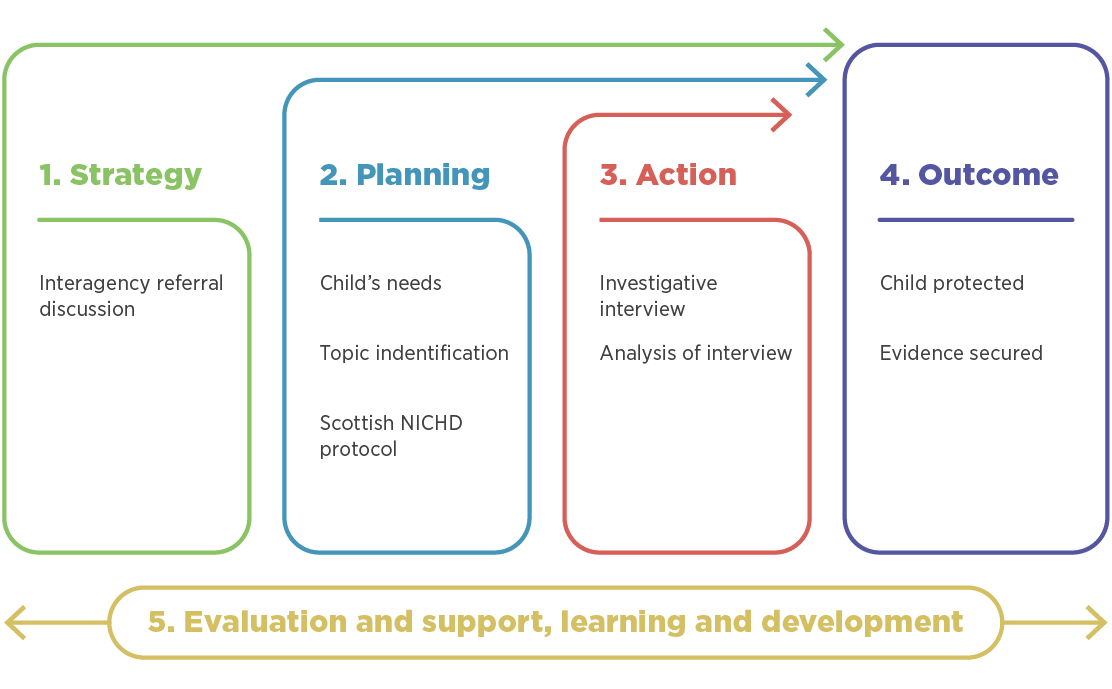

This comprehensive research enabled the team to develop the Scottish Child Interview Model for Joint Investigative Interviews: a five-component model of practice which is trauma-informed and aims to minimise the risk of further traumatisation, while seeking to achieve best evidence through improved planning and interview techniques.

Scottish child interview model for joint investigative interviews

1. Strategy

The strategy for the child protection investigation is determined by the interagency referral discussion (IRD). It identifies the aims and objectives of the joint investigative interview and should oversee and coordinate all stages of the child protection investigation.

2. Planning

The detailed plan for the child’s needs is developed by interviewers based on information provided by IRD participants, and importantly from discussions with people who know the child well:

- The plan starts by focussing upon the child’s strengths and resources. Interviewers consider how they can use these strengths to support the needs of the child in the interview, for example, considering whether the child has self-soothing behaviours which they could use during the interview.

- It goes on to consider whether the child has any complex needs and whether there is a need for further consultation.

- Interviewers consider the child’s stage of cognitive development, and ask focussed questions of people that know the child well, to develop the plan for the support they will need to participate in interview.

- The plan takes account of the child’s experiences of trauma and adversity, potential triggers and how the interviewers plan to support the child to remain within their Window of Tolerance (Siegel, 2001). This is the zone of arousal in which a person is able to function most effectively and is typically able to readily receive, process, and integrate information and otherwise respond to the demands of everyday life without much difficulty.

- Interviewers must consider the child’s speech, language and communication needs. Even if a child is described as having ‘normative development’, it is necessary to consider what this means for the child’s participation in interview.

- Taking account of their knowledge of the research and of the child’s circumstances, it is important that interviewers consider the child’s context and motivation to participate in interview and how they can best support them to do so.

- The child can be expected to bring their previous experience of relationships into the interview and interviewers must plan how they intend to build a relationship with the child in the interview.

- It is also important for interviewers to consider how they will support each other to undertake the interview.

The topic identification plan developed by the interviewers sets out the required information relevant to during, before and after the suspected incident/s. Taking essential elements of crimes and the grounds for referring to a children’s hearing into consideration, as well as what is known about the child’s circumstances, it sets out the topics to be explored during the interview. It is important that the topics to be addressed inform the immediate risk assessment and formal processes.

The Scottish NICHD Protocol provides a flexible framework to structure the interview and phrase appropriate prompts. It is combined with the plan for the child’s needs and topic identification plan to develop a bespoke and dynamic plan for the interview.

3. Action

Developing a plan in this way will lead to a child-centred joint investigative interview that secures the child’s best evidence at the earliest opportunity and minimises the risk of further traumatisation.

Interviewers must apply the following NICHD principles to the interview:

- Continue to develop rapport throughout the interview

- Address reluctance by the provision of non-suggestive support

- Adopt an appropriate questioning strategy

- Attempt to elicit free narrative recall (the child recounting their experiences in their own words with minimum input from the interviewers)

- Ensure that if more directive questions are required that these are paired with more open prompts

- Use breaks appropriately to support the needs of the child in the interview and to review and develop the plan for the interview.

Following the interview, it is essential that interviewers contribute to an analysis of what the child has said, as well as their presentation during the interview to inform further decision making and arrangements to protect the child.

4. Outcome

Robust analysis of the evidence and information secured during the interview ensures that the child [is] protected (and other children) and shows whether there is sufficient evidence secured to progress a criminal investigation and/or to establish grounds for referring to a children’s hearing.

5. Support and evaluation

To ensure that there is ongoing learning and development in the practice of joint investigative interviewing, the provision of regular support and evaluation of the interviewer is key.

Quality assurance and rigorous review, ensuring lessons are learned from practice are necessary if interview practice is to develop to a consistently high standard so that joint investigative interviews can be used as evidence in chief or hearsay evidence. Partner agencies such as the Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration (SCRA) and the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS) have committed to supporting the ongoing quality assurance of interviews.

A new comprehensive training programme for interviewers has been developed which underpins the new model of practice. The programme has been credit rated at Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF) level 9, and the project team are currently working closely with the Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC) to develop a new pathway whereby this programme will be recognised by the SSSC as specialist training and, as such, will have equivalent status to specialist awards issued by SSSC.

The way forward

There have been significant developments in joint investigative interviewing practice in Scotland. The Scottish Child Interview Model for Joint Investigative Interviews and the associated training programme (which lasts seven weeks with further reading and completion of exercises) is to be rolled out across Scotland by 2024.

The practice model and training programme have been developed to take account of messages from research and practice experience nationally and internationally. The project team has sought to develop a model of practice that is truly trauma-informed and places the needs of the child very much at the centre of the investigation. This paper seeks to emphasise the importance of non-suggestive support which is key to the child’s experience of the interview.

There are plans in place for more formal research to consider the impact of the new model of practice. However, with over 1000 interviews having already been conducted using the model, the early findings from the pilot sites are certainly encouraging.

Interviewers feel confident in their roles. All aspects of planning and conducting these interviews are truly ‘joint’, with social workers and police officers having a shared responsibility for all aspects of the interview.

The best thing about the new model is the depth of research and knowledge gained to ensure every child is afforded the most trauma free experience during the contact they have with the JII Team. (Fiona, Lanarkshire JII Team)

There is a clear difference in the level and quality of detail provided when using the new protocol. The interview is led more by the child/young person, accessing their free recall memory when responding to open prompts used by the interviewer. This has reduced the number of direct and suggestive questions being used, as they have provided the information needed without being asked directly. This means that the evidence is stronger as it is in the child/young person’s own words. (Davey, North Strathclyde Child Interview Team)

The model and the training programme will continue to be developed. For example, consideration is currently being given to the implementation of the model in remote and island locations. However, what is clear is that the landscape for forensic interviewing in Scotland now looks very different to when the Evidence and Procedure Review was first published back in 2015.

Children and young people who participate in joint investigative interviews can expect a trauma-informed interview, tailored to their individual needs. They can expect interviewers who have taken the time to plan how to support their participation in interview and who will be attuned to the child’s needs as they develop throughout.

Interviewers will have the knowledge and skills to secure best evidence and information during the interview, to inform court processes, as well as risk assessment and future planning for the child.

There are also links with other exciting areas of policy and practice development across Scotland. The Barnahus model aims to reduce the number of times that children have to recount their experiences to different professionals to take a more coordinated and collaborative approach, lessen trauma and speed up response time. Learning from the development of the model has already informed the development of training for age of criminal responsibility interviews. It will resonate with the implementation of the Promise, with trauma-informed, rights-based practice at its core.

References

- ALMERIGOGNA J, OST J, BULL R et al (2007) A state of high anxiety: how non-supportive interviewers can increase the suggestibility of child witnesses. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21, 7, 963-974

- ALMERIGOGNA J, OST J, AKEHURST L et al (2008) How interviewers’ nonverbal behaviors can affect children’s perceptions and suggestibility. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 100, 1, 17-39

- BROADERS SC and GODLIN-MEADOW S (2010) Truth Is at hand: how gesture adds information during investigative interviews. Psychological Science, 21, 5, 623-628

- HERSHKOWITZ I, LAMB ME, KATZ C et al (2015) Does enhanced rapport-building alter the dynamics of investigative interviews with suspected victims of intra-familial abuse? Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 30, 6–14

- HERSHKOWITZ I, AHERN EC, LAMB ME et al (2017) Changes in interviewers’ use of supportive techniques during the revised protocol training. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 31, 340–350

- HERSHKOWITZ I, MELKMAN EP and ZUR R (2018) When Is a child’s forensic statement deemed credible? A comparison of physical and sexual abuse cases. Child Maltreatment, 23, 2, 196-206

- KATZ C, HERSHKOWITZ I, MALLOY LC et al (2012) Non-verbal behavior of children who disclose or do not disclose child abuse in investigative interviews. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36, 12– 20

- KLEMFUSS, JZ, MILOJEVECH, HM, YIM, SI, RUSH, EB & QUAS, JA (2013) Stress at encoding, context at retrieval, and children’s narrative content. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 116, 3, 693-706

- LAMB ME, ORBACH Y, HERSHKOWITZ I et al (2007) Structured forensic interview protocols improve the quality and informativeness of investigative interviews with children: a review of research using the NICHD Investigative Interview Protocol. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31, 1201-1231

- LAMB M, HERSHKOWITZ I, ORBACH Y et al (2008) Tell me what happened: structured investigative interviews of child victims and witnesses. John Wiley & Sons Ltd

- LAMB ME, BROWN DA, HERSHKOWITZ I, ORBACH Y et al (2018) Tell me what happened: questioning children about abuse. John Wiley & Sons Ltd

- LA ROOY D and HALLEY J (2010) The quality of joint investigative interviews with children in Scotland. Scots Law Times, 24, 133-137

- LA ROOY D, LAMB ME and MEMON A (2011) Forensic interviews with children in Scotland: a survey of interview practices among police. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 26, 1, 26-34.

- LA ROOY D, NICOL A, HALLEY J et al (2012) Joint investigative interviews with children in Scotland. Scots Law Times, 30, 175-184

- LA ROOY D and BLOCK S (2013) The importance of scientifically analysing the quality of joint investigative interviews (JIIs) conducted with children in Scotland. Scots Law Times, 10, 77-78

- LA ROOY D, EARHAR B and NICOL A (2013) Joint investigative interviews (JIIs) conducted with children in Scotland: a comparison of the quality of interviews conducted before and after the introduction of the Scottish Executive (2011) guidelines. Scots Law Times, 31, 217-219

- MALLOY LC, BRUBACHER SP and LAMB ME (2013) ‘Because she’s one who listens’. Children discuss disclosure recipients in forensic interviews. Child Maltreatment, 18, 4, 245-251

- QUAS JA, WALLIN AR, PAPINI S et al (2005) Suggestibility, social support, and memory for a novel experience in young children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 91, 4, 315-341

- RICHARDS P, MORRIS S and RICHARDS E (2007) On the record: evaluating the visual recording of joint investigative interviews with children in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive

- SAYWITZ KJ, WELLS CR, LARSON RP et al (2019) Effects of interviewer support on children’s memory and suggestibility: systematic review and meta-analyses of experimental research. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 20, 1, 22-39

- SIEGEL DJ (2001) The developing mind: how relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. The Guilford Press

- SCOTTISH COURT SERVICE (2015) Evidence and procedure review report. Edinburgh: Scottish Court Service

- SCOTTISH COURTS AND TRIBUNAL SERVICE (2016) Evidence and procedure review – next steps. Edinburgh: Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service

- SCOTTISH COURTS AND TRIBUNAL SERVICE (2017a) Evidence and procedure review: child and vulnerable witnesses project – joint investigative interviews work stream project report. Edinburgh: Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service

- SCOTTISH COURTS AND TRIBUNAL SERVICE (2017b) Evidence and procedure review: child and vulnerable witnesses project – pre-recorded further evidence workstream project report. Edinburgh: Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service

- SCOTTISH EXECUTIVE (2003) Guidance on interviewing child witnesses in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive

- SCOTTISH GOVERNMENT (2011) Guidance on joint investigative interviewing of child witnesses in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- SCOTTISH GOVERNMENT (2021) National guidance for child protection in Scotland

- WATERHOUSE GF, RIDLEY AM, BULL R et al (2016) Dynamics of repeated interviews with children. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 30, 5, 713-721

- WATERHOUSE GF, RIDLEY AM, BULL R et al (2018) Mapping repeated interviews. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 1-18.

This report is published jointly by Iriss and Social Work Scotland.

1. Recommendation 2: Evidence and Procedure Review, Child and Vulnerable Witness Project, Joint Investigative Interviews Work-stream Project Report. June 2017.

2. NICHD Protocol is a framework for forensic interviewing of children.