Introduction

This evidence summary seeks to address the following question relating to the outcomes of involvement in social enterprises for young people with additional support needs:

- What are the benefits of social enterprise ventures such as cafés for young people with additional support needs?

- How does evidence from academic research and lived experience back up the approaches taken by [organisation redacted] as examples of good practice?

It identifies some key studies relating to the wide range of outcomes for young people with additional support needs from work- and employment-based social enterprise interventions and recommendations for good practice.

About the evidence presented below

We drew on a wide range of evidence, including academic research in the fields of social work and social care, disability studies and social sciences more broadly in relevant databases (e.g. ASSIA, ProQuest Public Health, SCIE Social Care Online, Social Services Abstracts) and manually searched key websites (e.g. Autism Network Scotland, Camphill Scotland, People First Scotland, Scope, Scottish Commission for Learning Disability, Scottish Human Rights Commission, Scottish Learning Disabilities Observatory, Scottish Strategy for Autism and Scottish Union of Supported Employment Scotland). We used a broad range of terms around work and employment developed iteratively as we conducted the searches, including variations on concepts including terms such as employment support, integrated settings, job carving, real work, supported employment, transition, transitional occupation, and work integration.

We identified evidence relating to young people with additional support needs by using a wide range of related terms. Additional support needs is a term used mainly in the Scottish literature as a result of Scotland-specific legislation and policy, including the Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2009. Synonyms for this concept and specific related conditions were used to identify relevant evidence, including learning disability, intellectual disability, autism, aspergers and Down's Syndrome. Although we searched for research and evidence using a wide range of terms including 'disabled people', and journal article titles include potentially problematic terminology have used the term 'disabled people' throughout the report to acknowledge the social model of disability valued by the client for this Outline.

The focus of the review was the impact of work experience provided through social enterprise organisation that take a person-centred, strengths based approach to supporting young people. We therefore searched for evidence produced about social enterprises, community enterprises, charities, voluntary organisations, and community groups under the assumption these kinds of organisations operate in a similar way to social enterprises, may also take the same approach to support, and may have evaluated the impact of this approach. We searched for terms including person-centred planning, strengths-based approach, and vocational profiling. Although the focus is on young people, we included work-based social enterprise interventions for adults with learning disabilities, as we anticipated there may be similarities between outcomes and effective approaches for different age groups.

Potential outcomes were identified in the organisational literature provided by the organisation that commissioned the review. These outcomes include those relating to mental health, social skills, employability, economic impact, environmental, social impact, social inclusion, and human rights. We included these as search terms, as a method of identifying relevant literature from the search results and to structure the review.

NDTi (2016) identify the need for evidence to support commissioners to base investment decisions on, particularly evidence about cost effectiveness. They regard the economic evidence as limited. More widely, we identified a limited number of studies overall assessing the non-economic impact of specific social enterprise or work-based interventions for young people with additional support needs. This may be because it is difficult to empirically measure the impact of such schemes, particularly in terms of solid outcomes such as increased employability, social skills or wellbeing for several reasons, including that people who participate in such programmes are also likely to participate in other activities or schemes to support positive outcomes and it is therefore difficult to isolate the standalone effects of one of these interventions. However, we identified some strong examples of qualitative research and have included these in this review.

Accessing resources

We have provided links to the materials referenced in the summary. Some materials are paywalled, which means they are published in academic journals and are only available with a subscription. Some of these are available through the The Knowledge Network with an NHS Scotland OpenAthens username. The Knowledge Network offers accounts to everyone who helps provide health and social care in Scotland in conjunction with the NHS and Scottish Local Authorities, including many in the third and independent sectors. You can register here. Where resources are identified as 'available through document delivery', these have been provided to the original enquirer and may be requested through NHS Scotland's Fetch item service (subject to eligibility).

Where possible we identify where evidence is published open access, which means the author has chosen to publish their work in a way that makes it freely available to the public. Some are identified as author repository copies, manuscripts, or other copies, which means the author has made a version of the otherwise paywalled publication available to the public. Other referenced sources are pdfs and websites that are available publicly.

Background

Employment for people with ASNs

Education Scotland (2018) define additional support needs (ASNs) as being both long- and short-term, or can simply refer to the help a child or young person needs in getting through a difficult period. Additional support needs can be due to:

- Disability or health

- Learning environment

- Family circumstances

- Social and emotional factors

Specific schemes to support young people with additional support needs are believed to be important to support a wide range of positive impacts, including occupational outcomes. Employment rates for disabled people in the UK are generally lower than that of the broader population, with an employment rate of 49.2% and an unemployment rate of 9.0%, in comparison to the employment rate of non-disabled people of 80.6% and an unemployment rate of 3.8%. (House of Commons Library 2018)

In terms of learning disabilities specifically, the trend is similar:

In 2017, 31 local authorities provided employment information on 14,085 adults across Scotland (60.7% of all adults). There were 1,219 adults in employment, which is 5.3% of all adults known to local authorities. A further 12,866 were not in employment (55.5%) and information was not recorded for 9,101 adults (39.3%). These figures are in comparison to an overall Scottish employment rate of 75.2%. (SCLD 2017)

The employment rate of people with a learning disability is very low – albeit there is some variance in the data available about how low...the employment rate for people with a learning disability is in the range of 7%-25% compared to a disability rate of 42% and an overall employment rate of 73%. Irrespective of the variance in the learning disability employment rate, the gap with the pan-disability and all-person employment rates is substantial. (McTier et al. 2016)

Although a significant proportion of disabled people may not be able to undertake employment, it should not be assumed disabled people cannot or do not want to work. Mencap, for example, argue that people with a learning disability have the same access to meaningful paid work as everyone else. As well as individual benefits for disabled people (Lackenby and Hughes 2008, pp.76-79), Scope (2014) argue that there are wider societal benefits to increasing employment for disabled people:

The UK economy could grow by £13 billion if disabled people were included. Workplaces across the country could benefit from the skills, experience and unique perspectives disabled people bring.

Scottish policy priorities

Below is an outline of key Scottish policy that may be used to identify where social enterprise interventions for young people with additional support needs are contributing to relevant strategic outcomes.

Scottish Government (2016) A fairer Scotland for disabled people (website)

A Fairer Scotland for Disabled People has five long-term ambitions aimed at changing the lives of disabled people in Scotland and ensuring that their human rights are realised. The plan includes halving the employment gap for disabled people. This plan is built around five key ambitions:

- Support services that promote independent living, meet needs and work together to enable a life of choices, opportunities and participation.

Health and social care support services are designed to meet – and do meet – the individual needs and outcomes of disabled people. - Decent incomes and fairer working lives.

Making sure disabled people can enjoy full participation with an adequate income to participate in learning, in education, voluntary work or paid employment and retirement. - Places that are accessible to everyone.

Housing and transport and the wider environment are fully accessible to enable disabled people to participate as full and equal citizens. - Protected rights.

The rights of disabled people are fully protected and they receive fair treatment from justice systems at all times. - Active participation.

Disabled people can participate as active citizens in all aspects of daily and public life in Scotland.

Scottish Government (2013a) Keys to life (website)

The keys to life is Scotland's learning disability strategy. Launched in 2013, it builds on 'The same as you?', the previous strategy which was published in 2000 following a review of services for people with learning disabilities. Its strategic outcomes are:

- A healthy life

- Choice and control

- Independence

- Active citizenship - which includes the aim to facilitate employment opportunities for people with learning disabilities

Scottish Government (2013b) Scottish strategy for autism (website)

The vision of the Scottish strategy for autism is that:

[I]ndividuals on the autism spectrum are respected, accepted and valued by their communities and have confidence in services to treat them fairly so that they are able to have meaningful and satisfying lives.

Its underpinning values are:

- Dignity: people should be given the care and support they need in a way which promotes their independence and emotional well-being and respects their dignity

- Privacy: people should be supported to have choice and control over their lives so that they are able to have the same chosen level of privacy as other citizens

- Choice: care and support should be personalised and based on the identified needs and wishes of the individual;

- Safety: people should be supported to feel safe and secure without being over-protected

- Realising potential: people should have the opportunity to achieve all they can

- Equality and diversity: people should have equal access to information assessment and services; health and social care agencies should work to redress inequalities and challenge discrimination

Scottish Government (2012) Opportunities for all: supporting all young people to participate in post-16 learning, training or work (pdf)

Opportunities for All brings together a range of existing national and local policies and strategies as a single focus to improve young people's participation in post 16 learning or training, and ultimately employment, through appropriate interventions and support until at least their 20th birthday. The Scottish Government state that the guiding principle for this policy is:

The Government's aim is to enable all young people to access and progress in learning and to equip them with the skills, knowledge and positive attitudes they need to participate and progress, where possible, to employment. In this way we look to improve the life chances of all of our young people, including those with additional support needs, through the provision of learning and training opportunities and the personal support they need to help them achieve and progress.

It includes the following commitment:

In delivering provision for young people, partners comply with the Additional Support for Learning Act and reflect the Getting It Right For Every Child (GIRFEC) Practice Model to ensure consistent, timely, post-16 transition planning.

Context

For young people with additional support needs, the transitional period from childhood to adulthood can include multiple barriers and challenges that may be addressed with the provision of specialist support. NDTi's (2016) scoping review of economic evidence around employment support found that supported employment for people with learning disabilities and individual placement and support (IPS) for people with mental health issues were the most effective models for getting people into paid jobs.

Aiken (2007) identifies several claimed advantages of social enterprises creating work with disadvantaged groups:

- About relation with client or users

- Close to the user

- More holistic and empathetic to the user

- More trusting relation with the user

- About the service

- Can reach the highly disadvantaged

- Can facilitate wider social inclusion for disadvantaged people

- Can deal with highly disadvantaged by offering multiple and flexible opportunities

- Provides a better quality service

- About the wider community links

- Close to the community

- Can make local connections to wide range of other organisations

- Delivers wider benefits: social and environmental

- About the organisational roles

- Good local intelligence

- Can offer innovation and develop niche markets

- Promise of financial sustainability

Young-Southward (2018) discusses the impact of employment on wellbeing outcomes for young people with additional support needs experiencing transition:

A key component of transition for the population with intellectual disabilities is finding appropriate daytime activity following school exit. Given that work is assumed to be a central component of adulthood, and the low employment figures for this population, those with intellectual disabilities may be excluded from this important component of adulthood. Furthermore, additional benefits of work, including increased social connectedness, may also be unavailable to adults with intellectual disabilities, further inhibiting opportunities to engage in adult social roles.

The impacts of transition from school can be health related, with research indicating that mental health can be threatened during this period of vulnerability for young people with learning disabilities:

The key health impact of transition on young people was on mental health, with young people experiencing high levels of anxiety during the transition period, and often exhibiting challenging behaviours as a result. Themes identified as contributing to these mental health difficulties included a lack of appropriate daytime activity following school exit; inadequate supports and services during transition; and the struggle to adjust to expectations for more 'grown up' behaviour. (Young-Southward 2011)

The Welsh Centre for Learning Disabilities and Shaw Trust (Beyer et al. 2008) interviewed 145 young people and their carers about their experiences of transition and employment. They collected information on the vocational input the young people had in their last year from their special school, college or employment organisation, and followed-up six months after leaving to identify how many had entered employment.

They explored what processes of transition planning lead to young people with learning disabilities gaining and keeping paid employment. Key findings for what works in supporting transition to employment for young people with learning disabilities were identified as:

- Promotion and support of employment as an option early in transition planning

- Involvement of skilled employment organisations in transition planning

- Access to individually tailored and flexible work experience, with on-the-job personal support when needed

- Provision of transition workers as a single point of information and support for young people and their families

- Consistent and high quality vocational training in schools and colleges.

- Challenge the idea that young people with learning disabilities are 'incapable' of employment

Social enterprises

Lackenby and Hughes (2008, p.91) identify social enterprises as having the potential to "provide powerful opportunities for people with learning disabilities to work within sectors or specific projects that interest them, and can also provide learning opportunities and skills development". Calò et al.'s (2017) systematic review explored the question: do social enterprises provide improved outcomes in comparison with usual care in health and social care systems? They identified six papers that explored social enterprise as a substitute to usual care, focusing on different interventions:

- Parenting programme for reducing conduct problems with children

- Social activities and peer support for people with leg ulcers

- Providing residential care for adults with chronic conditions

- Providing community support for adults with mental health issues

- Work therapy station for mentally ill patients

- Providing healthcare nutritional programme for women

They also explored studies that focused on social enterprises in a more collaborative setting:

- Reading service for people affected by stroke

- Work integration social enterprise for people with mental health issues, people with intellectual disabilities, and young homeless people

- Community development activities for children, women with breast cancer and adults with chronic conditions

- Housing and support for people with HIV

- Physical activity for people affected by stroke and with cancer

- Befriending groups for people with mental health issues

They found that positive outcomes of social enterprises included:

[P]ositive results in terms of interactions with communities and families, the inclusion of beneficiaries, feelings of engagement, perceptions of social support and increased sense of self-worth.

They conclude:

[T]here is no evidence to support the role of social enterprise as a substitute for publicly owned services. However, there is evidence to show that where social enterprise operates in a collaborative environment, enhanced outcomes can be achieved, such as connectedness, well-being and self-confidence.

This review explores some of the kinds of enhanced outcomes identified by Calò et al. (2017) within social enterprise projects designed to support young people with additional support needs.

Social enterprises supporting employment

McTier et al. (2016) identify social enterprises as one source of supported employment for young people with ASNs. We identified several examples of supported employment across the UK in the catering sector. For example, Petroc Catering Social Enterprises run a range of social enterprise groups, including in the area of catering. Their North Devon Campus cooks a two course lunch once a week at a sheltered housing association, a café and restaurant which runs five days a week, a purpose-built building containing a professional kitchen and café area. Their Mid Devon Campus runs a take-away service, café and restaurant open to members of the public five days a week.

Campbell et al. (2017) identify several key points they argue create the conditions for positive outcomes with employer engagement:

- Communication

- Continuity of contact

- Job matching

- Familiarity training

- Job coaches

- Supported internships

Using telephone interviews and focus groups with disabled people and their carers, Secker et al. (2003) explored perspectives on the values that should underpin social firms. They suggest that indicators of good practice include:

- User/worker participation in the firm's development and operation

- The availability of expert advice to enable informed choice about payment, with payment at the minimum wage rates or higher for those who choose this

- Opportunities for workers to develop to their full potential

- A workforce comprising disabled and non-disabled workers

- The involvement of carers and local socio-economic agencies in developing the social firm

McTier et al. (2016) identify several cross-cutting features for social enterprises and other forms of supported employment to result in positive outcomes for young people with ASNs. These include:

- Person-centred approach

- Long-term support

- Employment focused from the start

- Robust household-based assessment of benefit implications of moving into work

- Working with parents and carers to raise expectations

- Family commitment to moving into work

- In-depth and thorough vocational profiling

- Good quality work experience placements in real work environments

Social enterprises may be able to address some of the challenges identified by McTier et al. (2016), which include:

- Parental caution

- Local gaps in next step options

- Increasing difficulties securing work experience placements

- Challenges bridging the gap between work experience and real jobs due to differences in working hours and payment

Some social enterprises are involved in supported internship schemes, for example through programmes like Project SEARCH. Project SEARCH is an American internship model of training in which people with learning disabilities are assisted in securing and retaining full-time, paid permanent employment (Young People's Learning Agency 2010). However, there is limited evidence of the impacts of Project SEARCH programmes to date:

Recent monitoring and evaluation efforts suggest promising employment outcomes for Project SEARCH participants, but there has not yet been a rigorous impact evaluation with a large sample to demonstrate that these outcomes are substantially better than they would be if the participants had only relied on services and supports that are available outside of Project SEARCH. (Mamun et al. 2016)

We have included the findings of several studies of Project SEARCH interventions throughout the review where thematically appropriate.

Person-centred approach

This review focuses on evidence relating to schemes that support young people with additional support needs and other barriers to employment that take an explicitly person-centred approach. This is a key approach to social enterprises working with young people with additional support needs.

McTier et al. (2016) suggest that a person-centred approach to supported employment is a key aspect of what works in supporting young people with ASNs:

Person-centred approach, which focuses the support on the needs, skills and aspirations of the individual and then progresses them at their own pace. In some cases, this means moving backwards as well as forwards along the model, and so is not a linear 'conveyor belt'. If provision is in a group setting, the group should be small in size and allows for individual needs to be met. Similarly job coach or advisor caseloads should be kept small and manageable.

Relevant evidence from the literature supports the suggestion that a person-centred approach can lead to positive outcomes for young people with ASNs. For example, Kaehne and Beyer (2014) suggest that a person-centred approach can result in increased participation of young people and carers at review meetings and a significant shift in topics discussed during the transition planning process compared with other less person-centred approaches. However, they emphasise that although "person-centred planning can impact positively on some aspects of transition planning, it may be too optimistic to expect radical improvement in other areas".

Calò et al. (2017) found in their systematic review of social enterprise outcomes that:

[T]he clearest positive outcomes occurred among measures such as well-being, connectedness, confidence and empowerment, and that these outcomes were more obvious when social enterprise operated in a more collaborative setting.

Ridley and Hunter (2007) produced a report to provide information to people involved in commissioning services to support people with learning disabilities and/or Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in real paid jobs. In it they provide recommendations from research for good practice in this area. In it, they include personalisation as a core principle for good practice:

Clear principles emerge from the increasing body of international research into supported employment and the recent provider statements about quality standards. These principles come from research which has included services users' and others' views about best practice and quality in supported employment...

These principles offer a defining framework for considering how best to support people with learning disabilities and/or ASD to access and sustain real paid jobs…

Personalisation – people with learning disabilities and/or ASD should be treated as individuals and support should be customised for each person. The emphasis should be on finding out what each person wants to do and where his/her skills and aspirations lie and using these in the job finding and development process.

Strengths-based approaches

McNeish et al. (2016) review the efficacy of asset based approaches for people with learning disabilities and to evidence the impact these approaches can have on people's lives. Through analysis of the literature, 40 interviews and a workshop, the researchers explored the impacts associated with a strengths and capacities focused approach. Whilst emphasising that there is "no 'off the shelf' set of practices that can be adopted", the authors suggest that the values and principles of strengths- or asset-based approaches are:

- Instead of starting with the problems, start with what is working and what people care about

- Working with people – "doing with", rather than "doing to"

- Helping people to identify and focus the assets and strengths within themselves and their communities, supporting them to make sustainable improvements in their lives

- Supporting people to make changes for the better by enhancing skills for resilience, relationships, knowledge and self-esteem

- Support for building mutually supportive networks which help people make sense of their environments and take control of their lives

- Shifting control over the design/development of actions from the state to individual and communities

Outcomes found to be associated with asset based approaches included participants' sense that they were supported to realise their potential.

Krabbenborg et al. (2013) designed a method for examining the effectiveness of the strengths-based Houvast approach in Dutch services for homeless youth. They argue that despite the hardships and challenges faced by homeless young people, they often use their own resources and personal power to make successful transitions into adulthood. Citing Williams et al. (2001), they suggest that:

Both internal factors (e.g. self-esteem and self-efficacy, intelligence, perseverance) and external factors (e.g. affectional ties that encourage trust and autonomy) can contribute to the development of resilience.

They also suggest that supportive relationships with significant people through informal ties can play an important role in young people's development of high self-esteem and self-efficacy. Citing Cocks and Boaden (2009), the authors argue that the strengths based approach has been found to have a positive association with the number of hospitalizations, quality of life, social functioning and social support among persons with mental illness.

The Houvast approach is a strengths based model that was originally developed for people with a psychiatric disability. In the follow-up to their 2013 paper, Krabbenborg et al. (2017) used interviews and focus groups with workers and homeless adolescents, and a review of the evidence supporting the approaches of the project, to explore the impact of the project and the extent to which it adhered to strengths based models:

The results showed that homeless young adults in general improved on quality of life, satisfaction with family relations, satisfaction with finances, satisfaction with health, depression, autonomy, competence, and resilience. In addition, homeless young adults had fewer care needs, and a higher percentage was employed or in school at follow-up. Contrary to our expectation, all homeless young adults showed a decline on satisfaction with social relations.

A limitation of the research included that it was not possible to control the variable of when homeless young adults left the shelter facility so their duration of 'exposure' to the intervention differed.

Social enterprise outcomes

We identified a body of research specifically focusing on interventions in social care and support through social enterprise delivery models. The most relevant of these to the original enquiry are presented in the sections below.

To provide context for the general outcomes associated with social enterprise employment interventions, the six studies below provide an overview of the themes found in the majority of research outputs around the topic.

Bayer and Kaehne (2011) produced a report to and identify the extent to which the Getting A Life (GAL) programme helped more people with learning disabilities to enter paid employment than those without the intervention. The Getting A Life Employment Programme involved several activities:

- Joint planning arrangements

- Person-centred Review (PCR) training

- Person-centred Assessment training

- Leadership Programme

- Personal Budgets and Direct Payments

- Employment /Self-Employment workshops

- Inclusion Web

- Consultancy

- Development of materials

- Identification of structural barriers

The goal of GAL was to "investigate and demonstrate the nature and extent of the barriers to employment faced by young learning disabled people…[and] to increase the number of young people with learning disabilities entering paid employment by helping local teams to overcome them".

Destination data for people involved in the GAL programme compared to people who did not participate indicated that GAL had some impact on employment outcomes:

There were differences between the two samples in respect of employment, with the GAL cohort reporting an employment rate of 18.8% compared to 6.3% for the nonGAL matched comparison sample. The match control group produced employment rates post education near to the average for England taken from NI146 returns for 2009/10 while the GAL cohort was three times higher. There was also a large difference in the use of training places taken up, with the GAL sample having no such placements registered. Personal Development placements, mainly made up of day service of skill centre placements, was higher for GAL that the comparison, but in total this did mean that the level of NEET (Not in Education, Employment or Training) was also a little lower in the GAL sample than the comparison group.

The figures are encouraging that the GAL approach has had an impact on employment outcomes, with an employment rate 3 times higher than for the matched comparison group. This is important evidence for the impact of individual approaches on employment. However, the pattern for the two samples was still dominated by the number of "education" places taken up by leavers, largely college places taken up post-special school.

Macaulay et al.'s (2018) research focuses on the ways in which social enterprises might act on the social determinants of health, addressing a gap in research taking account of the wide range of stakeholders involved in social enterprises and their differing characteristics, through qualitative case studies using in-depth semi-structured interviews and a focus group with a wide variety of stakeholders from three social enterprises in different regions of Scotland. The authors argue that social enterprises have health impacts through different outcomes:

- Engendering a feeling of ownership and control

- Improving environmental conditions (both physical and social)

- Providing or facilitating meaningful employment

Several limitations of the study are identified, including the small sample size, its nature as a non-comparative study that means it was not possible to identify whether there was any advantage to the support being delivered through a social enterprise model, and most significantly that the study "did not attempt to 'measure' health, or even to measure impact on the social determinants of health".

In their study of the social return on investment of a social enterprise intervention for people with developmental disabilities, Owen et al. (2015) examine the impact of training, administrative, and job coach support to five social enterprises for which persons with developmental disabilities are the non-share-capital partners. Change-based outcomes resulting from the project for different stakeholders included:

| Stakeholder | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Volunteers | Skills development |

| Foundations Program Participants | Independence, social participation, well-being

Independence and social participation Independence ( self-determination) Emotional well-being Physical well-being |

| Apprentices | Material well-being (earning power)

Independence |

| Partners | Material well-being (earning power)

Independence, social participation, well-being Independence ( self-determination) |

| Families | Emotional well-being

Physical well-being Material well-being (earning power) Material well-being (savings in home care) |

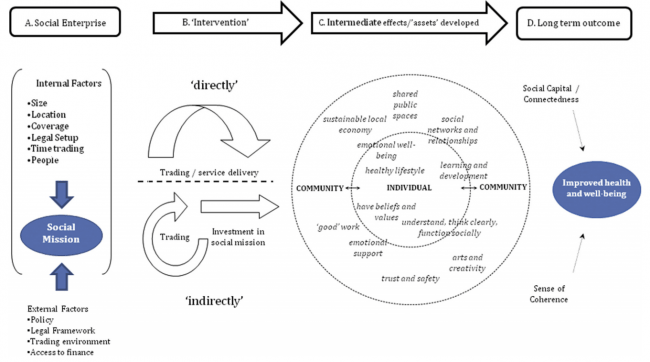

Roy et al. (2014) conducted a systematic review of empirical research on "the impact of social enterprise activity on health outcomes and their social determinants". Several of the social enterprise projects they analysed were work integration or employment focused. They developed a conceptual model of social enterprise intervention, to describe their hypothesis that "a chain of causality exists from the trading activity of the social enterprise through to health and well-being of individuals and communities".

The authors identify a gap in knowledge around the causal mechanisms in terms of how social enterprises effect public health outcomes, and suggest:

There is a clear need for research to better understand and evidence causal mechanisms and to explore the impact of social enterprise activity, and wider civil society actors, upon a range of intermediate and long-term public health outcomes.

In their study of a social enterprise intervention for young people experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles, which offered clinical mentor training, mental health support, outreach, vocational skills support, small business skills support and establishment of a vocational co-operative, Ferguson et al. (2007) suggest that through the social enterprise project, homeless young people can "acquire vocational and business skills, clinical mentorship, and linkages to services that would otherwise not be available to them". The authors suggest that the strengths based approach taken to the intervention and the comprehensive nature of the health and mental health support offered through the intervention are significant factors of its success.

Ferguson and Islam (2008) used focus groups to explore homeless young people's experiences of the social enterprise discussed above, which offered engagement, mentoring, job training, business skills and service linkage, to identify outcomes-related themes. These included:

- Mental health outcomes:

- Family respect

- Self esteem

- Motivation

- Goal-orientation

- Employment outcomes

- Job skills

- Employment search

- Labour networks

- Future employment plans

- Service related outcomes

- Relationships with staff

- Service engagement

- Social networks

- Behavioural outcomes

- Respite from street life

- Destructive behaviour

- Societal outcomes

- Positive aspects of homeless

- Image with authorities

In the sections below we identify evidence relating to specific outcomes on themes relevant to the organisation that commissioned this enquiry. These are:

- Mental health

- Social skills

- Life skills

- Employment

- Economic benefits

- Community and social impact

Mental health impacts

Key themes from annual reports and other documents from social enterprises that work to support young people with ASNs suggest the main mental health impacts of these interventions may include:

- Discrimination, bullying, isolation, loneliness and sense of hopelessness

- Confidence, self-worth and resilience

- Humanising impact

- Reducing isolation

We searched the literature and analysed evidence that reported on the impact of relevant interventions. The most robust outputs are presented below, which reflect the above outcomes.

Ferguson (2012) used a mixed methods approach (structured interviews and qualitative focus groups) with 16 young homeless people to identify outcomes of a social enterprise for homeless young people in the United States. Using findings from her study alongside "global precedents", she argues that social enterprises can have positive outcomes for young homeless people in terms of strengthening their existing human and social capital, giving them job skills and employment, and supporting their mental health. Mental health related outcomes of involvement in the social enterprises were family respect, self-esteem, motivation and goal-orientation:

Regarding mental health benefits, the youths receive ongoing mental health services tailored to their individual conditions and treatment goals, as well as referrals to health, mental health, and social services.

Froggett et al. (2015) explored the impact of Gift Shop, a creative, arts-based engagement project run in Old Trafford by 42nd Street between May – June 2015:

The idea was to work with young people to enable them to set up their own shop, make their own products and to sell them to their local community. The Shop aimed to introduce young people to the idea of 'Gift Giving' and to the work of 42nd Street with any money raised from this venture to be re-invested into local activity.

Using interviews and questionnaires, the researchers gathered information about the experiences of 39 young people, 44 members of the public and 8 professionals involved in the project. Mental health outcomes identified were:

- The sense of achievement that the young people felt raised self-esteem and confidence and gave them a sense of being part of the local community

- Gift Shop provided a space in which a diverse group of young people found it possible to think of themselves in a positive and optimistic way, rather than as stigmatised casualties of institutions or systems

- The creative sessions demonstrated to the young people the pleasure to be gained in craft and artwork its potential as a means of self-expression

- Positive relationships were formed by the young people both with one another and the professionals working with them. This extended the networks of friendship and support available to them, including their awareness of mental health support services provided by 42nd Street

- The groups of which the young people were a part benefitted from a share of the proceeds of the shop, and the young people took pride in this material outcome

Macpherson et al. (2015) studied the impact of visual arts interventions on young people with complex needs. Using a case study method of ten arts workshops, the authors explored how arts interventions may enhance young people's resilience. They found that arts interventions can increase young people's sense of belonging and ability to cope with difficult feelings. Although not work-based, the project within the study was a social enterprise that used the Resilience Framework as an approach planning and intervention for individual young people:

It is ecological, thereby addressing many aspects of a young person's life, including developmental, social, psychological and physical spheres, recognising the inter-relationship between these different areas. There is a political and socio-economic aspect to the framework – interventions with approaches that enhance a disadvantaged young person's material wellbeing are given important consideration.

The resilience measure the researchers used showed only slight positive changes in respondents' wellbeing. However, the qualitative findings illustrate in more detail the impacts of the project for participants. Themes include: sense of responsibility, sharing enjoyment through non-verbal dialogue and mutuality, confidence, ability to focus and becoming able to externalise and accept difficult feelings. In terms of what approaches supported positive outcomes, trends included a non-judgemental atmosphere.

The authors emphasise the importance of acknowledging that outcomes and changes in young people's resilience as a result of the social enterprise art intervention are not "unequivocally good or straightforward" and stressed the importance of not over-romanticising arts activities.

Roy et al. (2014) identified five studies that they suggest provide:

[L]imited evidence that social enterprise activity can impact positively on mental health, self-reliance/esteem and health behaviours, reduce stigmatization and build social capital, all of which can contribute to overall health and well-being.

In her report for United Response, Wellard (2008) used a case study design involving semi-structured interviews with six programme participants, six employers, four relatives and six support professionals, as part of a qualitative approach to explore the outcomes of participating in supported employment for adults with moderate to severe learning disabilities.

This study identifies a number of benefits for people with learning disabilities of participating in supported employment, several of which relate to mental health:

- Increased confidence and independence both in and outside of the work setting

- Greater self-esteem from feeling that they are playing a valued role

- Feeling happier

- Having a greater structure to their day: all participants highlighted the benefits of keeping busy

Social skills

Key themes from annual reports and other documents from social enterprises suggest the main impacts of these interventions in terms of young people's social skills may include:

- Good communication skills appropriate eye contact, exchange of information, dealing with requests, problem solving etc.

- Confidence - being less reserved

- Making and holding eye contact

- Initiating conversations

- Holding meaningful conversations

- Being more expressive

We searched the literature and analysed evidence that reported on the impact of relevant interventions.

Groundwork's (2018) youth employment programme, Progress, offered access to specialist support for young people in Coventry and Warwickshire to get back into employment, education, training or apprenticeships:

The programme offers tailored individual and group support including work placements, practical living skills, mental health support and maths and English qualifications.

The programme will run until 2018 and reports are anticipated following its conclusion. Outcomes reported by participants on the project website so far include several mental health related impacts.

Froggett et al. (2015) report that an outcome of study of the Gift Shop project is that young people learnt to work collaboratively with one another and enjoyed the sociability and co-operation of a shared enterprise.

Wellard (2008) found that the intervention on supported employment for adults with moderate to severe learning disabilities they evaluated led to a wider network of friends and more social contact with non-disabled people through working in mainstream settings.

Life skills

Key themes from annual reports and other documents from social enterprises suggest the main impacts of these interventions in terms of young people's practical skills may include:

- Practical capacities - for example preparing hot and cold food safely and hygienically

- Good personal presentation

- Understanding risks and measures they have to take to keep themselves and others safe

We searched the literature and analysed evidence that reported on the impact of relevant interventions.

Bennett and Cunningham (2014) conducted a qualitative evaluation of a healthy cookery course in Ireland designed for adults with mild to moderate intellectual disability. The study obtained the views of course participants and the views of managers hosting the course through semi-structured interviews. The authors identified that the cookery course "provided participants with an important social outlet in which to learn essential occupational skills" and suggest that the outcomes "could particularly influence the diets of adults with an intellectual disability moving into independent living". In discussion, the authors identify the importance of meaningful social interaction in the course, suggesting that "cooking as a group provided an additional social network for each course participant" and that this was viewed by participants as "one of the most valuable aspects of the course" Additionally, as the resulting social network included individuals with and without intellectual disabilities, the authors argue that this kind of intervention is beneficial for "meeting the social and emotional needs of this population".

Employment

Key themes from annual reports and other documents from social enterprises suggest the main impacts of these interventions in terms of the employability of young people with ASNs may include:

- Increased knowledge of specific topics: e.g. food hygiene modules

- Qualifications: e.g. entry level SVQ - Retail, Front of House, Hospitality or Facilities Services

We searched the literature and analysed evidence that reported on the impact of relevant interventions.

Anderson and Galloway (2012) investigated the impact of Fife Arts and Crafts Enterprise Training (FACET), a publicly funded initiative. The central aims of the programme include the ambition "to create social enterprise/self-employment opportunities for people affected by disability and mental health problems". The authors suggest that the initiative has resulted in positive outcomes that are the result of their approach to support:

The outcomes of the FACET programme are encouraging thus far. Since its inception, several new firms have been created, and 'alumni' of FACET have moved on to start firms of their own. Additionally, other types of enterprise creation include several social enterprises with ongoing links to, and support from, FACET...Other positive outcomes include the development of employability amongst participants. FACET enjoys good rates of employment post-FACET training, both within the FACET environment and outside it.

The national scheme Project SEARCH, was evaluated by Kaehne (2016) to identify the impact of the 17 UK programmes. Using graduate data about employment status and information from interviews with families, Kaehne concludes that the programmes did have an impact on employment outcomes:

Although data collection practices varied across the various data sources, the available data reveal some good employment outcomes for participants, well above the national level of employment of people with learning disabilities.

A limitation of this study is that the purpose of the research was not to identify the extent to which the 17 programmes were following the Project SEARCH model (described in the study appendix), so it cannot be used to determine whether the method of intervention and its constituent parts (e.g. work hours, method of employment, kind of support available) can or does always result in improved employment outcomes for participants and if so which elements are required to create the conditions for success.

Wehman et al. (2012) conducted two case studies of Project SEARCH programmes and identified the additional supports provided to young people with ASD that increase successful employment on graduation from high school. Supports specific to students with ASD included: providing intensive instruction in social, communication, and job skills; visual supports; and work routine and structure.

Ferguson's (2012) research with young homeless people found that involvement with a social enterprise had employment outcomes, which she identified as job skills, employment search, labor networks and future employment plans:

[T]hrough social-enterprise involvement, homeless youths learn vocational and business skills, gain access to a social enterprise, and receive continuous mentoring from peers and supportive staff.

Froggett et al. (2015) report that an outcome of study of the Gift Shop project is that young people began to learn new skills which if further developed could enhance their future employability.

Wellard (2008) found that the supported employment intervention they evaluated led to increased incomes: "most were on low incomes before working and so even though benefit rules mean that they are only £20 a week better off in work, this makes a real difference".

Tan (2009) examined the Barista Express Programme, a hybrid transitional-supported employment that used a social enterprise model of a café in Singapore, to support people with mental illnesses (the majority of whom had been diagnosed with schizophrenia). Using a Work Behavior Inventory (presumably by the people running the scheme) they tracked changes in work behaviour across the course across five scales: work habits; work quality; personal presentation; co-operativeness and social skills. They found that all participants who completed a 20-month training programme demonstrated significant improvements in work behaviour before leaving the transitional training at the café. Limitations of the study are its small sample size (25), its lack of methodological transparency and quantitative nature which means the participants' perspectives about features of the intervention that led to successful outcomes have not been identified.

Economic benefits

Cooney and Williams Shanks (2010) argue that social enterprises, such as restaurant and food services, street cleaning, manufacturing, maintenance, pest control, retail and furniture upholstery, create job opportunities and needed products and services for the local community.

Froggett et al.'s (2015) study of the Gift Shop project identified that people from the community using the social enterprise as customers found that the quality and professionalism of the project had a positive impact:

At the centre of visitors' enjoyment and appreciation of the project was the importance of community involvement in planning, making gifts and setting up the caravan as the Gift Shop...Along with the sense of community, the items made by the young people and put on sale in the caravan were seen as attractive and of high quality...There was also an appreciation that the staff in the shop were very friendly, welcoming and professional - this encouraged people to enter the caravan and experience a really warm ambience whilst browsing.

Social Value Lab (2013) conducted a Social Return on Investment Analysis for North Lanarkshire Council, where a Project Search intervention is run. This intervention includes an element of supported employment.:

The model runs over an academic year and students work in three placements between September and June. They start and finish each day in their Project Search classroom on site where they discuss what they have been doing that day, participate in skills training and carry out supported job searches with the support of their Job Coach.

Social Value Lab identified positive outcomes for participants using face to face interviews with participants and service managers. They then used a set of financial proxies to give a market value to mostly intangible outcomes, to identify potential cost savings and financial benefits for individuals and wider society. The authors suggest that for every pound of investment in Project Search, £3.96 social value is created. However, if the SROI approach is to be adopted it is important to consider both its merits and limitations to ensure the methodology is responsibly used (see for example Maier et al. 2015).

Zaniboni, et al. (2011) studies the working plans of people with "mental disorders" employed in italian social enterprises. They found that most of their sample of 140 people intended to keep working, which they suggest demonstrates the effectiveness of the social enterprise companies they were exploring. A limitation of this research is that it does not focus on actual employment status and only considers individuals' plans for working.

Community and social impacts

Key themes from annual reports and other documents from social enterprises suggest the main impacts of these interventions in terms of the community and social impacts include the wide variety of people who may use a social enterprise such as a cafe. Documentation from social enterprises suggests that this is viewed as having a normalising effect and supports integration rather than division between disabled and non-disabled people.

Aiden and McCarthy (2014) argue that everyday interactions and greater public education about disability will increase understanding and acceptance of disabled people. Secker et al. (2003) found that carers believed that positive views about work stemmed from a concern with the principle of normalisation. They identified three central values:

- Enabling disabled people to participate in all stages of developing and running a firm

- Integrating disabled and non-disabled workers

- Ensuring that the work available was fulfilling and that opportunities were available for people to develop their knowledge and skills

Froggett et al. (2015) report several community and social outcomes from report that an outcome of study of the Gift Shop project:

- The shop provided an accessible local interface between young people and residents

- The fact that the shop was organised around creative activity, helped to counter any perceptions that young people were merely a destructive nuisance in the area, and showed the potential for the further breaking down of boundaries between them and other residents in their community

Good practice

In an international study of training and employment opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities, Parmenter, T (2011) identifies a series of conditions for what makes for successful inclusive employment programmes and workplaces. These include:

- Values base: commitment to the principle of equity for people with intellectual disabilities

- Programme size: smaller agencies found to be more likely to provide integrated employment. Economies of scale result in loss of personalisation and limit effective outcomes

- Support needs assessment: training in basic living skills, finding the right environment for the individual

- Person-centred planning: centring the person’s wishes and desires in the decision-making process

- Links to parents: families’ attitudes towards children’s capabilities critical determinant in support for community-based employment options

- On-job support and job coaching:

- Individuals should be able to choose the kind of job they enter

- Work should allow individuals to obtain independence from paid support, such as reliance on job coaches;

- Support should be tailored to each person’s needs; • ‘getting to know the person well’ is the key to successful workplace support

- The possibility that a person may not be ready for work should be accepted when appropriate

- Existing contacts and other natural supports should be used as inroads into the workplace

- Benchmarking quality: need for effective benchmark indicators e.g.

- Meaningful competitive employment in integrated work settings

- Informed choice, (wherein the person is allowed to express a preference) control and satisfaction

- Level and nature of supports

- Employment of individuals with significant disabilities

- Amount of hours worked weekly

- Number of people from programme working regularly

- Well-coordinated job retention system

- Employment outcome monitoring and tracking system

- Integration and community participation

- Employer satisfaction

- Workplace culture: a congenial workplace culture has been found to be critical for the successful placement and maintenance of people with intellectual disabilities in integrated work environments. It helps the development of strong relationships between workers with and without disabilities

- Sustainability: factors explaining success in integrated employment outcomes

- Existence of strong, clear and unambiguous state developmental disabilities agency policies, rules and programmatic requirements intended to support a clearly articulated agency preference for, and commitment to, integrated employment for people with developmental disabilities

- Use of funding incentives to encourage the expansion of integrated employment opportunities, and/or funding disincentives to discourage the use of facility-based employment and non-work services;

- Liberal definition of the kinds of employment arrangements which qualify for SE funding;

- Adequate state agency staffing dedicated to employment; 51

- Investment in on-going training and technical assistance for agency staff;

- Commitment to supporting organizational change among facility-based (sheltered) providers moving to integrated employment settings; and

- Use of a comprehensive data-tracking system focused on integrated employment outcomes

References

Aiden, H and McCarthy, A (2014) Current attitudes towards disabled people. Scope (pdf)

Aiken, M (2007) What is the role of social enterprise in finding, creating and maintaining employment for disadvantaged groups? Office of the Third Sector (pdf)

Anderson, M and Galloway, L (2012) The value of enterprise for disabled people. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 13(2), pp.93-101 (paywalled or author repository copy)

Baum, NT and Edwards, M (2014) The cascading transition model: Easing the challenges of transition experienced by individuals with autism and their support staff. International Public Health Journal, 6(4), pp.323-339 (paywalled)

Bennett, AE and Cunningham, C (2014) A qualitative evaluation of a healthy cookery course in Ireland designed for adults with mild to moderate intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 18(3), pp.270-281 (paywalled or author copy)

Beyer, S et al. (2008) What works? Transition to employment for young people with learning disabilities (pdf)

Calò, F et al. (2017) Collaborator or competitor: assessing the evidence supporting the role of social enterprise in health and social care. Public Management Review (open access)

Campbell, M et al. (2015) Pathways to success: progression pathways for learners with learning difficulties or disabilities. Petroc College of Further & Higher Education (pdf)

Clifford, J et al. (2013) Measuring social impact in social enterprise: the state of thought and practice in the UK. London: E3M

Cocks, E and Boaden, R (2009) Evaluation of an employment program for people with mental illness using the Supported Employment Fidelity Scale. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 56(5), pp.300-306 (paywalled)

Cooney, K and Williams Shanks, TR (2010) New approaches to old problems: Market-based strategies for poverty alleviation. Social Service Review, 84(1), pp.29–55 (paywalled)

Education Scotland (2018) What are additional support needs? (website)

Erzurumluoglu, B and Askin, S (Eds) (2016)Barrier-free production model: integration of people with disability into public and business life through learning (pdf)

Ferguson, KM (2012) Merging the fields of mental health and social enterprise: Lessons from abroad and cumulative findings from research with homeless youths. Community Mental Health Journal, 48(4), pp.490-502 (paywalled)

Ferguson, KM (2007) Implementing a social enterprise intervention with homeless, street-living youths in Los Angeles. Social Work, 52(2), pp.103-112 (paywalled)

Ferguson, KM and Islam, N (2008) Conceptualizing outcomes with street-living young adults: grounded theory approach to evaluating the social enterprise intervention. Qualitative Social Work, 7(2), pp.217-237 (open access)

Froggett, L et al. (2015) Gift shop: creative social enterprise with young people for mental health and wellbeing (author copy)

Garcia, JA et al. (2016) Employability of individuals with learning disabilities and long-term unemployed: current practices and future opportunities in Sheffield. University of Sheffield (author copy)

Groundwork (2018) Youth employment programme has helped over 200 young people to 'progress' (website)

House of Commons Library (2018) People with disabilities in employment (website)

Kaehne, A (2016) Project SEARCH UK – evaluating its employment outcomes. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 29(1), pp.519–530 (paywalled)

Kaehne, A and Beyer, S (2014) Person-centred reviews as a mechanism for planning the post-school transition of young people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58(7), pp.603-613 (paywalled)

Krabbenborg, M et al. (2017) A cluster randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of Houvast: a strengths-based intervention for homeless young adults. Research on Social Work Practice, 27(6), pp.639-652 (open access)

Krabbenborg, M et al. (2013) A strengths based method for homeless youth: Effectiveness and fidelity of houvast. BMC Public Health, 13(359), pp.1-10 (open access)

Lackenby, H and Hughes, J (2008) Achieving successful transitions for young people with disabilities: a practical guide. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers (ebook available through NHS Scotland)

Macaulay, M et al. (2018) Differentiating the effect of social enterprise activities on health. Social Science & Medicine, 200(1), pp.211-217 (open access)

MacPherson, H et al. (2015) Building resilience through group visual arts activities: Findings from a scoping study with young people who experience mental health complexities and/or learning. Journal of Social Work, 16(5), pp.541-560 (paywalled or author pre-print)

Maier, F et al. (2015) SROI as a method for evaluation research: understanding merits and limitations. Voluntas, 26(1), pp.1805–1830 (open access)

Mamun, AA et al. (2016) Prospects for an impact evaluation of Project SEARCH: an evaluability assessment. Mathematica Policy Research (website)

McKeith, J (2011) The development of the outcomes star: a participatory approach to assessment and outcome measurement. Housing Care and Support: a journal on policy, research and practice, 14(3), pp.98-106 (paywalled or author copy)

McNeish, D et al. (2016) Building bridges to a good life: a review of asset based, person centred approaches and people with learning disabilities in Scotland. SCLD (pdf)

McTier, A (2016) Mapping the employability landscape for people with learning disabilities in Scotland. SCLD (pdf)

Mencap (2018) How many adults with a learning disability have a paid job? (website)

National Development Team for Inclusion (NDTi) (2016) A scoping review of economic evidence around employment support (pdf)

Owen, F et al. (2015) Social Return on Investment of an Innovative Employment Option for Persons with Developmental Disabilities. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 26(2), pp.209-228 (paywalled)

Parmenter, T (2011) Promoting training and employment opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities: international experience. International Labour Office (pdf)

Powell, M and Flynn, M (2005) Promoting independence through work. In Grant, G et al. (Eds.) Learning disability: A life cycle approach to valuing people. Maidenhead: Oxford University Press. pp.398-416 (pdf)

Purvis, A et al. (2012) Project SEARCH evaluation: final report. Centre for Economic Inclusion/HM Government Office for Disability Issues (pdf)

Ridley, J and Hunter, S (2007) Learning from Research about Best Practice in Supporting People with Learning Disabilities in Real Jobs (pdf)

Rotheroe, NC and Miller, L (2008) Innovation in social enterprise: achieving a user participation model. Social Enterprise Journal, 4(3), pp.242-260 (paywalled)

Roy, M et al. (2014) The potential of social enterprise to enhance health and well-being: A model and systematic review (paywalled)

Scope (2014) A million futures: halving the disability employment gap (pdf)

SCLD (2017) Learning disability statistics Scotland 2017 (pdf)

Scottish Government (2016) A fairer Scotland for disabled people - our delivery plan to 2021 for the United Nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (website)

Scottish Government (2013a) Keys to life (website)

Scottish Government (2013b) Scottish strategy for autism (website)

Scottish Parliament (2009) Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2009 (pdf)

Secker, J et al. (2003) Developing Social Firms in the UK: A contribution to identifying good practice. Disability & Society, 18(5), pp.659-674 (paywalled)

Tan, BL (2009) Hybrid transitional-supported employment using social enterprise: a retrospective study (paywalled or author copy)

Wehman, P et al. (2012) Project SEARCH for youth with autism spectrum disorders increasing competitive employment on transition from high school. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 15(3), pp.144-155 (paywalled or author copy)

Wellard, S (2008) Being something that I've always wanted to be: an evaluation of a supported employment service for adults with learning disabilities. United Response (pdf)

Whittingham, L (2017) Changes in employment skills and quality of life for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities during transition from pre-employment to cooperative employment. Doctoral thesis, Brock University (Open Access) Young Enterprise (2017) Programmes impact report 2016/17 (pdf)

Williams, NR et al. (2001) From trauma to resiliency: Lessons from former runaway and homeless youth. Journal of Youth Studies, 4(2), pp.233-253 (paywalled or preprint)

Young People's Learning Agency (2010) Enterprise and employment for people with learning difficulties and/or disabilities: A report following three regional conferences (November–December 2009) (pdf)

Young-Southward, G (2011) How transition to adulthood affects health and wellbeing in young people with learning disabilities (website)

Young-Southward, G (2018) The impact of transition to adulthood on health and wellbeing in young people with intellectual disabilities. PhD Thesis, University of Glasgow (pdf)

Zaniboni, S et al. (2011) Working plans of people with mental disorders employed in italian social enterprises. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 35(1), pp.55-58 (paywalled or author copy)

The content of this work is licensed by Iriss under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 2.5 UK: Scotland Licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/

The Institute for Research and Innovation in Social Services (IRISS) is a charitable company limited by guarantee. Registered in Scotland: No 313740. Scottish Charity No: SC037882. Registered Office: Brunswick House, 51 Wilson Street, Glasgow, G1 1UZ