Key points

- Legal recognition in recent years has confirmed Scotland's Gypsy Travellers as a distinct ethnic minority with their own history, culture and customs. Their contribution to Scotland’s cultural diversity should be respected and valued.

- This history, up to present times, involves oppression, denial of identity and culture, and generally poor treatment by public sector bodies.

- State agencies including those involved in health, social care and social work, must incorporate culturally sensitive practice into their services to Scottish Gypsy Travellers.

- Human rights approaches are pivotal to efforts to provide culturally sensitive services.

- Local authorities and health partnerships should provide specialised Scottish Gypsy Traveller awareness training for social work staff who might encounter community members.

- Evidence shows that effective advocacy can provide a better experience of services by Scottish Gypsy Traveller users. Such services should be funded, promoted and the subject of common referral.

- Regulatory and inspection bodies (SSSC, Care Inspectorate, Audit Scotland) should include considerations of culturally sensitive practice in their scrutiny functions and findings.

- All agencies must consider how to engage participation from Scottish Gypsy Travellers, for example, staff and foster carer recruitment, local and national policy makers, and local user forums.

- The social work profession, founded on a basis of anti-oppressive practice and social justice, should lead in the effort to improve public services for Scotland's Gypsy Travellers.

Introduction

It should shock us all that denial of identity, forced assimilation, racial harassment, daily discrimination, and a lack of understanding and respect for culture and difference, are all reported as regular experiences of Scotland’s Gypsy Travellers (Amnesty International, 2012a; BEMIS, 2011; Cemlyn and colleagues, 2009; Greenshields et al, 2009; MECOPP, 2014; Scottish Parliament, 2012). With accompanying marginalisation and poverty issues, referrals for various types of social services interventions are inevitable, whether for care and support in old age or with disability, support over child care issues, or criminal and youth justice.

What should underpin all forms of practice, whatever the setting, is a Human Rights approach. This approach - designed to improve human rights for all citizens (Scottish Government, 2015) – is recognised by the Scottish Government in terms of the Scottish National Action Plan (SNAP) launched on International Human Rights day in December 2013. Human rights are often misunderstood and seen as restrictive when they should be viewed as a useful framework for planning, action and partnership working. Fear can operate as a barrier within organisations: 'of litigation or of not having enough resources to meet the rights of everyone, or of balancing the competing rights of different groups' (Alliance NHS Scotland, 2014). Human rights are incorporated into international law and are an aspect of every government policy, and Scottish and UK legal enactment. 'Equality Proofing' includes testing against human rights legislation. A basic knowledge to frame approaches to the Gypsy Traveller community can result in a better experience for users as well as workers, better outcomes and of course reduced chance of litigation (this is illustrated in the United Nations film 'Path to Dignity' which shows the positive effect on human rights training on police officers in Australia).

The need for social workers to know about human rights approaches is stressed from the outset because it needs to be. Official Scottish Government findings over the past fifteen years, as well as other public sector agency reports and those from human rights organisations point to continued pejorative attitudes and failures. These can only be described as 'institutional discrimination', a term which became well known in the UK after the publication of the MacPherson report into the killing of London black teenager Stephen Lawrence (Government UK, 1999).

These issues are well known to representative organisations of social workers, resulting in self-reflection and action by the Scottish Association of Social Workers (BASW, 2009; BASW, 2010) and UNISON (UNISON Scotland, 2011). This paper, drawn together by individuals from a social work background alongside Gypsy Traveller community members, is intended to help the process of understanding and leadership by the social work profession that might result in improvement.

The Scottish Parliament accepted in 2001 (Scottish Parliament, 2001) that the preferred generic term should be a capitalised 'Scottish Gypsy Traveller(s)'. In Scotland, Roma migrants are those who have moved to this country from European Union accession countries (Poland, Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Hungary, Estonia, Romania, and Bulgaria). The term 'Roma' is used loosely here as some European Gypsy Traveller populations (such as many Spanish Gitani) do not consider themselves such. A large proportion of these populations were wiped out in the Nazi Holocaust and those who survived were often forced to give up their nomadic way of life during and after WW2 (Renee Cassin, 2015). While the lives of these migrants are often blighted by poverty and disadvantage (EHRC, 2013) their issues are different (although often similar in their 'home' countries) from those encountered by Scottish Gypsy Travellers and will not be covered in this paper. 'Settled Community' is the term used when discussing Gypsy Travellers for the majority non-Traveller population.

Identity and history

Gypsy Travellers have an important place in modern day Scotland with a heritage and culture that should be celebrated and valued. The fact that they are often not, points to deep seated prejudices that should be positively challenged. Some history can help with improving understanding.

Gypsy Travellers have been present in Scotland since at least the 16th Century and perhaps as early as the 12th Century (Dawson, 2007). Although there has been intermarriage with other ethnic groups, they have always had a core who have followed a nomadic lifestyle, with occupations and income sources, such as seasonal harvesting or tinsmithing (the linguistic origin of the pejorative word 'tinker') that have suited this. Scrap metal dealing is a contemporary example pursued by some Gypsy Travellers, but others in the modern-day range from teachers to labourers. Scottish Gypsy Travellers report (as do their European counterparts) erosion of traditional occupational opportunity in recent years resulting in further economic marginalisation. Although poor formal education can be an issue, it is not always so and many Scottish Gypsy Travellers are high achievers with university degrees. As well as the love of travel, they also enjoy the unifying characteristics of art and crafts, music, a sense of group belonging, and a shared experience of oppression (ACTS, 2011). Language is diverse but words of Romani origin, collectively known as 'Cant' are universally used, and some can be traced back to the Indian sub-continent origins a thousand years ago. Some words have passed into universal use by the settled community: e.g. kushti, barrie, gadgie, deek, gav, chore, divi, raj. Religious observance ranges across Christian religions and to atheism, with 'born again' Christian belief currently in vogue (Cemlyn, 2008). Habits vary: some Travellers eat butter and not 'impure' margarine, some drink only unstrained tea; others will not eat out; some will not eat 'the baker boy's bread (Dawson, 2007). As in European Gypsy Traveller culture, strict hygiene rules apply (Fraser, 2005) and men are normally segregated from women and children. Marital customs vary and the possessions of deceased persons may be burned to ward off 'bad karma' (Dawson, 2007).

Of importance to social workers, family, kinship and children enjoy a central place in Gypsy Traveller life and culture. This is worth emphasising as the practice of children being home-educated in the occupational skills needed for survival is an issue, and can mean early assumption of adult responsibility. This can be misinterpreted as dangerous and even result in misplaced and culturally insensitive child protection concern (Cemlyn, 2008; Turbett, 2010).

Numbers of Scottish Gypsy Travellers are difficult to report accurately. The 2011 census identified them as a separate ethnic group for the first time with over 4000 individuals reporting this status (National Records of Scotland, 2013), representing 0.1% of Scotland's population. However, research sources suggest a figure of 20-23,000 (Clark, 2006; ACTS, 2011), while community insiders (including the co-authors of this paper) estimate a population of 50-60,000. Such uncertainties and the attitudes that surround them reflect the active denial of identity by dominant society until very recent times, with social policy actively working to suppress lifestyle and culture and eradicate what was perceived as a 'social disease' (Dawson, 2007). This was starkly carried out in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by active removal of Gypsy Traveller children from their families and placement in the colonies – described by Cemlyn (2008) as 'systematic child abduction' and 'cultural genocide'. In 1945, Perthshire County Council established a site in Bobbin Mill in Pitlochry with deliberately planned sub-standard accommodation to promote a settled lifestyle and eventual accession to standard council housing (Taylor, 2004). This 'Tinker Experiment' (sic) failed but the site is still there today – a living example of past racist social policy. It is no surprise that many should prefer to merge into the settled community: not to do so can result in difficulty in finding permanent employment and regular encounters with racist attitudes to the detriment of health and well-being (Lloyd and Ross, 2014).

The provision of sites for Gypsy Travellers by Scottish local authorities became mandatory in 1971; it took many years to get this underway but by 2001 there were 39 sites in 27 of the 32 council areas. Following the abolition of statutory requirement in 2001, numbers of sites reduced to 32 by 2009 (Scottish Government, 2009). This trend has accompanied an exponential increase in Gypsy Travellers using 'unauthorised' sites (ibid). Traditional sites used by family groups for generations which underpinned their seasonal wanderings are often now blocked off from access. Scottish Gypsy Travellers have strong clan and family ties within their own communities, and conflict can arise when different families are forced together on 'official' sites, which are consequently avoided by some.

Experiences and challenges

The benchmark for any contemporary view of the problems faced by Scotland's Gypsy Travellers is the report with recommendations compiled by the Scottish Government Equal Opportunities Committee in 2001 (Scottish Parliament, 2001). This covered all aspects of public service delivery, including health, education, accommodation, policing and criminal justice, and personal social services. One of the latest reviews by the same Committee took place in 2012 (Scottish Parliament, 2012) when members were 'appalled' to learn of the situation still prevailing. In a government paper that reflects the anger and frustration of Committee members, the evidence heard included: a population still not properly quantified; 50% of the population spending at least part of their lives without ready access to running water; very poor location of local authority sites (e.g. brownfield sites or those adjacent to rubbish dumps and deemed unsuitable for residential development); uncertainty of GP provision; poor health (particularly among those living in settled houses); 'shockingly low' life expectancy; persistent bullying and prejudice (reported by 92% of young Gypsy Travellers); continued use of racist and derogatory language towards the community; children at school being discouraged from speaking Cant; and poor outcomes across the health and well-being spectrum (Scottish Parliament, 2012).

This stark catalogue confirms the picture presented in other reports of recent years. An Amnesty International Report (2012a) found some examples of good practice, but in general 'very slow progress' among local authorities in taking up the 2001 recommendations concerning their responsibilities. It should be stressed that features of disadvantage apply equally to Gypsy Travellers who live in permanent housing but who are members of this ethnic minority (studies have shown that those who live in permanent housing suffer poorer mental health due to issues such as isolation and friction with neighbours – Lloyd, 2011). There is also a bitterness felt by some about feeling forced to give up a travelling lifestyle because of lack of accommodation options and other disadvantages (Scottish Parliament, 2012).

Another Amnesty International Report (2012b) looked at media coverage of Gypsy Travellers, finding that that over a four-month period in 2011 there were 190 articles in the national and local press, with 48% presenting a negative picture, 28% positive and the rest neutral. Of concern was the finding that of the 78 reported comments attributed to local politicians, only four were positive and 48 were negative (Turbett, 2010 quotes racially prejudiced statements by Scottish MPs in the House of Commons). Typically, press coverage reinforced negative stereotypes such as criminality and hygiene issues. Mention here should also be made of the popular Channel 4 TV show 'My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding' which has contributed to negative stereotyping and to have caused '...long term harm to the educational and social inclusion of Gypsy, Roma and Traveller children… including physical and sexual assault, racist abuse and bullying, misinformation and hostile questioning, resulting in damage to the self-esteem of children and withdrawal from school' (Rene Cassin, 2015). A Scottish Social Attitudes survey found that half of those surveyed would not want their child taught by a Gypsy Traveller primary school teacher (qualified by the notion that as they moved around they would be unsuitable), and that 37% would be unhappy if a close relative formed a relationship with a Gypsy Traveller even though 65% believe Scotland should be rid of all forms of prejudice (Scottish Social Attitudes Survey, 2010). Media-supported attitudes will impact on those who deliver services and influence their own views and approaches – it would be disingenuous to assume social work staff will be immune to such influence.

A significant challenge for social workers is the mistrust and suspicion they face from the Gypsy Traveller community. This is based, not unreasonably, on a legacy of discriminatory dealings with social work departments and fears of children being taken away from family kin and culture (Cemlyn, 2008; Morron, 2002). This can be overcome by effective advocacy through organisations that provide such a service, such as MECOPP – the Minority Ethnic Carers of People Project). However, there is a dearth of advocacy for such a marginalised, dispersed and unrepresented group whose members typically have little understanding of official agendas and processes. Turbett (2010) provides a Scottish case example whereby a perceived child protection issue (children whose needs were initially thought to be neglected) was changed through effective advocacy to one of agreement by agencies and the family – the children's situation could be improved through support with housing and education rather than solutions perceived as punitive and reactive.

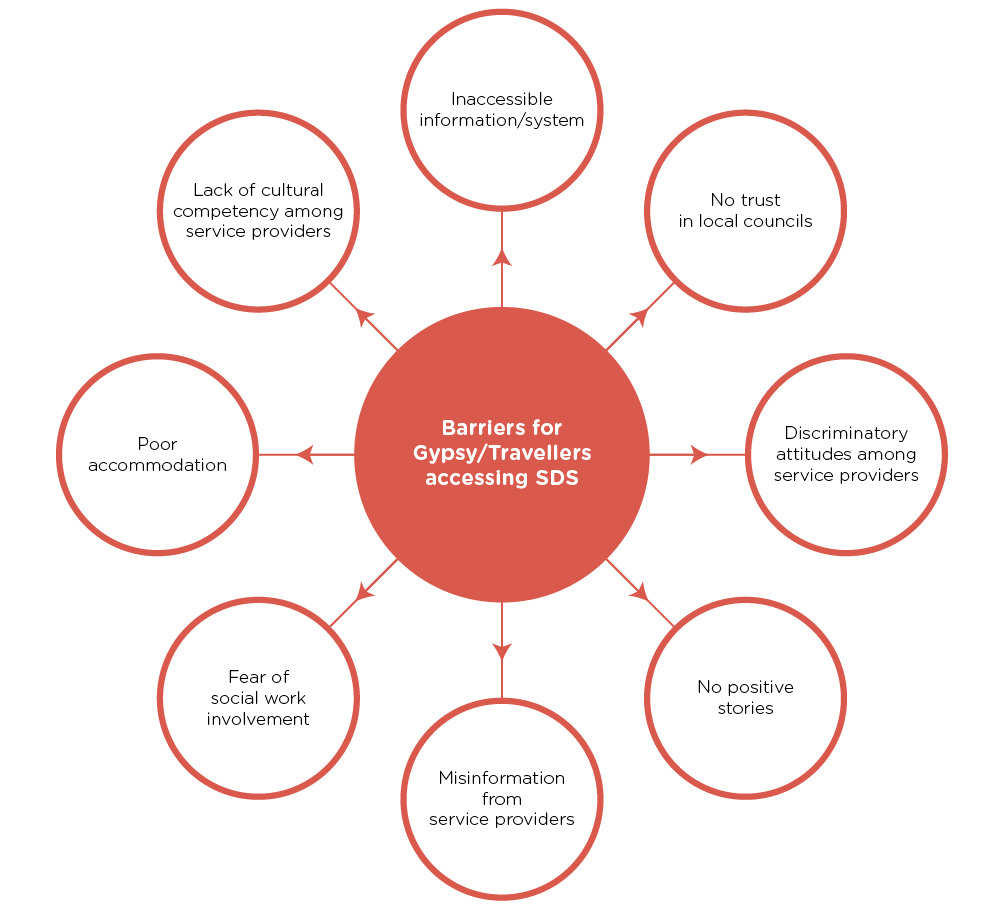

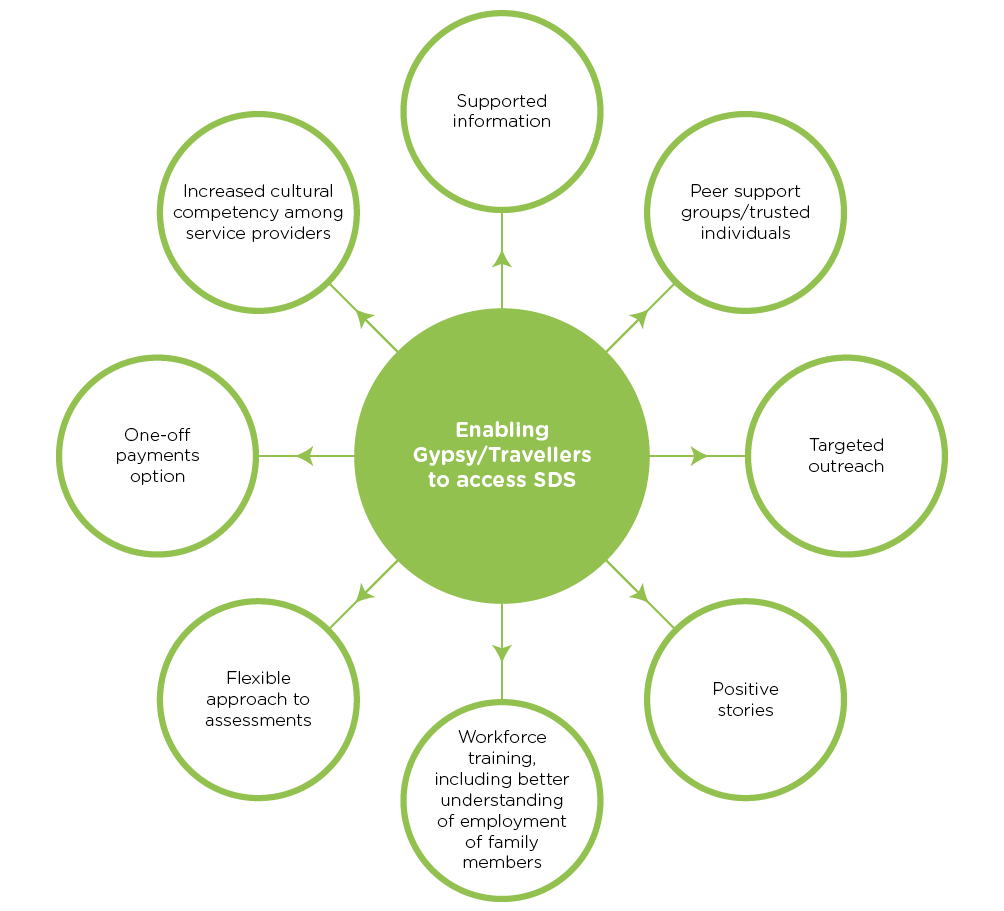

Another challenge is the need to explore solutions to problems other than the ones often sought by the settled community where family and kinship support in times of difficulty are often absent. Gypsy Travellers with their traditionally strong kinship ties will better suit interventions that support family care arrangements rather than those involving a directly provided service (MECOPP, 2015). Self-directed support (SDS) seems ideally suited but is, as experienced so far, problematic. The MECOPP report recognised several barriers to SDS uptake (see fig. 1 below) and provided their suggested solutions for enabling access (fig. 2).

Social workers involved in criminal justice must also bear in mind the experience of well-documented discrimination by Scottish Gypsy Travellers (Renee Cassin, 2012). While there is little evidence that Gypsy Travellers are effectively protected from racial abuse by others, there is plenty suggesting that unfounded stereotypes concerning criminality lead to unfair treatment by police officers with a high level of likelihood of custodial sentence (ibid). Once in the prison system, cultural and educational disadvantage (e.g. illiteracy) can result in higher than average levels of re-offending (ibid). It is also reported that the use of ASBO legislation to manage poor relations between Gypsy Travellers and their settled community neighbours is also problematic: it will inevitably be based on the values and norms prevalent within the latter (Cemlyn, 2008). This is especially the case when lack of a formal education can result in Gypsy Travellers being pushed into defensive posturing which is interpreted as threatening by others.

Given that national and local social policies are based upon research (examples have been quoted in this paper), there are problematic issues in the case of Gypsy Travellers. Okely (1983), an academic expert on their situation in the UK, states:

'Policy questions are inevitably set by those in power and restrict what needs to be learned; even research with the democratic and benevolent institutions will fail, if the questions of relevance are set by the uninformed.'

Beresford (2013) looks in detail at the enablers and barriers to involvement in research by the subject themselves (he includes Gypsy Travellers) and provides concise recommendations for how these can be overcome at every level. Failure to address these issues can adversely impact on the work of social services agencies who are reliant on research to inform cultural competence.

The framework for practice

This section provides an overview of the broad framework set by the Scottish Government, incorporating a human rights perspective on how culturally sensitive services, including social work, should be delivered to Scottish Gypsy Travellers. Social work managers need to understand this framework so that they can ensure local policies, priorities and guidelines are proofed against it. Social workers need to know likewise in terms of specific interventions in their day-to-day practice. The social work profession, founded on values of justice and anti-oppressive practice should lead other partner agencies.

Following a test case (MacLennan v Gypsy Traveller Education and Information Project, 2008), Scottish Gypsy Travellers enjoy full legal protection as a recognised minority ethnic group. This is against a background of similar developments across European Union countries.

The Equality Act 2010 supersedes and incorporates previous race relations legislation. It operates a binary role alongside the Human Rights Act 1998, which reflects obligations under previous United Nations and European declarations. In 2004, a judgement in the European Court of Human Rights (Connors v UK, 2004) found that '...there is a positive obligation on the part of contracting states by virtue of Article 8 to facilitate the Gypsy way of life.' (ERRC, 2004). A new public sector equality duty became law in April 2011 which placed a general duty on public sector organisations to eliminate unlawful discrimination, promote opportunity and foster good relations. The Scottish Government followed this up with some specific initiatives including Scottish National Action Plan (SNAP), which aimed to address gaps and inconsistencies in the realisation of human rights for all in Scotland, including in health and social care (Alliance NHS Scotland, 2014). SNAP's approaches include a promise of 'participation' and 'empowerment' that should be applied to the Scottish Gypsy Traveller community (ibid). The fourth priority for SNAP is to '...enhance respect, protection, and fulfilment of human rights to achieve high quality health and social care' (Scottish Government, 2015).

In terms of a general professional responsibility social workers will be aware that the Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC) Codes of Practice, section 1.5, obliges them to 'work in a way that promotes diversity and respects different cultures and values.' (SSSC, 2016). Also of relevance is the self-explanatory SSSC Employer's obligation to 'provide good quality induction, learning and development opportunities to help social service workers do their jobs effectively and prepare for new and changing roles and responsibilities.' (ibid). The Scottish Association of Social Workers (SASW) include in their code of ethics the clause '...that social work practice should address the barriers, inequities and injustices that exist in society' (SASW, 2014).

Best practice and Scottish Gypsy Travellers

This section looks at how the experience of Gypsy Travellers with public agencies might be improved, and draws upon macro and micro examples from home and abroad that point towards improved practice.

Unfortunately, the experience of Romani Gypsy Travellers in Europe, many of whom live in the former Eastern Europe, is, in some instances, worse than that experienced in the UK (far right politically inspired murderous attack on communities in Hungary is an example). A rights group reported that 'Roma rights exhibit the lowest level of implementation across Europe' (Romani CRISS, 2002). In 2011, the European Union (EU) determined a Roma Strategy to ensure basic improvement in the fields of health, education, employment and housing in member countries. Lipott (2012) states that 12 countries have adopted these and allocated funding for inclusion policies. Sweden and Slovenia have tried to positively move beyond them.

Sweden has introduced specific legislation protecting the Romani Chib language spoken by many Roma citizens. It has also funded measures to improve the educational attainment of children at school. Sweden has a national Roma Council along with other national and regional associations: these are not formalised representative groups but the Roma Council does have government representation and drafts laws and proposals for government to protect and promote their interests (ibid).

In Slovenia, legislation was introduced in the 1990s to protect the indigenous Roma minority and this included specific policies regarding education, culture, local government provision, housing and the promotion of political participation. The Law on Roma Community (2007) established a Roma Community Council to deal with Roma interests, rights and international co-operation and brought about other measures to improve their situation. With a settled Roma community who live in physical isolation from mainstream Slovenian society, of whom only 40% live in brick built houses, it is recognised that there is a long way to go in achieving satisfactory levels of social integration.

While these European examples tell us little about personal social services, we can look to Newfoundland in Canada for an initiative to improve the cultural sensitivity of social workers to ethnic minorities. Their communities contain a First Nations population who have suffered historical marginalisation and oppression. Using their professional Code of Ethics (which are not unlike those in Scotland) as a basis, the Newfoundland and Labrador Association of Social workers have drawn up a set of eight Cultural Competence Standards which could usefully be applied within the social work profession in Scotland and be made subject to scrutiny by the regulatory and inspection bodies.

Within Scotland there are examples of good practice which can be further developed. In recent years MECOPP has provided cultural awareness training that has involved Scottish Gypsy Traveller community members. That same organisation has also provided useful research and practice guidance on matters such as the use of self-directed support with Gypsy Travellers. Specialist advocacy remains a scarce and hard-to-obtain resource, but when used there is evidence of good outcomes for all: the UK Association of Gypsy Women have provided advocacy in a Scottish case where a child self-excluded from school due to bullying. This resulted in agreement for an independently conducted scoping exercise by a worker who had undergone awareness training, and a good outcome for the child concerned (reported verbally to the authors of this paper). Advocacy is the subject of a previous Iriss Insight (Stewart and McIntyre, 2013) which usefully reviews advantages and surrounding issues.

New Zealand are attempting to make their services more in tune with the needs of their indigenous Maori community, who make up more than half of referrals to children and family services. They have developed the Tuituia assessment model which is designed to reflect Maori concepts of wellbeing, including the collective nature of caring (New Zealand Government, 2013) which is similar to the ‘My World’ assessment triangle for children used in Scotland (Scottish Government, 2005).

Conclusions – the way forward

Initiatives including those flowing from the Scottish Government’s SNAP initiative are trying to address the scandalous lack of progress in achieving better basic human needs outcomes for Scottish Gypsy Travellers. This involves changing cultures within organisations that have failed to address inequalities and service deficits in the past; it can only come about through the creation of a culturally competent workforce alongside the involvement of Scottish Gypsy Travellers in shaping services and policies. If government is indeed serious about these matters it should be subject of comment by the statutory regulatory and inspection bodies in official reports.

The issues discussed apply across the board of public sector organisations but are particularly pertinent in social work given its tradition of anti-oppressive practice. At this point in time, a specialised Scottish Gypsy Traveller advocacy service is required, as is the promotion and take up of awareness training. Social work has always struggled with the dilemma of care versus control in its operations at micro and macro levels, and nowhere is this starker than in its history of dealings with Scotland’s Gypsy Travellers – it is time for some leadership on the issue.

References

- ACTS Church and Society Network (2011) A report on the church's attitude to the travelling community in Scotland (PDF). [accessed 16/11/16]

- Alliance Health Care and NHS Health Scotland (2014) A human rights approach to health and social care (PDF). [accessed 16/11/16]

- Amnesty International (2012a) On the margins: local authority service provision for Scottish Gypsy Travellers (PDF). [accessed 16/11/16]

- Amnesty International (2012b) Caught in the headlines: Scottish media coverage of Scottish Gypsy Travellers (PDF) [accessed 16/11/16]

- British Association of Social Workers (2009) Hard travelin (PDF), Rostrum Magazine, July, p.12-13.

- British Association of Social Workers (2010) End Gypsy Traveller discrimination, Rostrum Magazine, April, p.8.

- BEMIS (2011) Gypsy Travellers in contemporary Scotland – the 2001 inquiry into Gypsy Travellers and public sector policies: 10 years on (PDF).

- Beresford, P (2013) Beyond the usual suspects: towards inclusive user involvement – research report.

- Cemlyn S (2008) Human rights and Gypsy Travellers: an exploration of the application of a human rights perspective to social work with a minority community in Britain, British Journal of Social Work, 38, 1, 153–73

- Cemlyn, S, Greenshields, M and Burnett, S et al (2009) Inequalities experienced by Gypsy and Traveller communities: a review (PDF). EHRC research report.

- Clark, C (2006) Defining ethnicity in a cultural and socio-legal context: the case of Scottish Gypsy Travellers, Scottish Affairs, 54, 39–57

- Dawson, R (2007) Empty lands: aspects of Scottish Gypsy Traveller survival. Alfreton: Robert Dawson

- Equality and Human Rights Commission Scotland (2013) Roma and the Council of Europe's framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

- European Roma Rights Centre (2004) Connors v UK (PDF). [accessed 16/11/2016]

- European Commission (2015) Literature review and identification of best practice on integrated social service delivery part 1 (PDF).

- Fraser, A (1995) The Gypsies, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell

- International Federation of Social Workers (2012) Statement of ethical principles [accessed 17/11/2016]

- Lipott, S (2012) The Roma as a protected minority? Policies and best practices in the EU (PDF) Romanian Journal of European Affairs, 12, 4, 78–97.

- Lloyd, M (2011) Equally connected – Edinburgh and the Lothians. Final report (PDF). [accessed 16/11/2016]

- Lloyd, M and Ross, P (eds) (2012) Moving minds – Gypsy Travellers in Scotland. Edinburgh: MECOPP

- Minority Ethnic Carers of People Project (2015) Self-directed support and Gypsy Travellers (PDF). [accessed 16/11/16]

- Morron, D (2002) Negotiating marginalised identities: social workers and settled travelling people in Scotland, International Social Work, 45, 3, 337–51

- National Records of Scotland (2013) 2011 census: key results on population, ethnicity, identity, language, religion, health, housing and accommodation in Scotland, Release 2A (PDF). [accessed 16/11/16]

- Newfoundland and Labrador Association of Social Workers (2016) Standards for cultural competence in social work practice. [accessed 16/11/2016]

- New Zealand Government (2013) The Tuituia Assessment Framework guidelines (PDF). [accessed 16/11/16]

- Okely, J (1983) The Traveller Gypsies Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

- Renee Cassin Organisation (2012) An overview of discriminatory treatment of Gypsies, Travellers and Roma. [accessed 16/11/16]

- Renee Cassin Organisation (2015) Factsheet: Gypsies, Travellers and Roma in the UK and Europe. [accessed 16/11/16]

- Romani CRISS (2002) Roma and the Council of Europe's Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (PDF). [accessed 28/11/16]

- Scottish Association of Social Workers (2014) Code of ethics (PDF). [accessed 16/11/2016]

- Scottish Government (2005) Getting it Right for Every Child. [accessed 16/11/16]

- Scottish Government (2009) Gypsies / Travellers in Scotland: the twice yearly count, No 15. [accessed 16/11/16]

- Scottish Government (2015) Supporting the implementation of Scotland's national action plan for human rights. [accessed 16/11/16]

- Scottish Government Social Research (2011) Scottish social attitudes survey 2010: attitudes to discrimination and positive action (PDF). [accessed 12/11/16]

- Scottish Parliament (2001) Inquiry into Gypsy Travellers and public sector policies. [accessed 16/11/16]

- Scottish Parliament (2012) Equal Opportunities Committee 3rd Report 2012 Session 4, Gypsy Travellers and Care (PDF).

- Scottish Social Services Council (2016) SSSC codes of practice for Scottish social services workers and employers. [accessed 19/12/16]

- Stewart, A and McIntyre, B (2013) Advocacy: models and effectiveness, Iriss Insight 20

- Turbett, C (2010) Rural social work practice in Scotland. Birmingham: Venture Press

- United Nations Human Rights (2011) A path to dignity (film) [accessed 16/11/16]

- UNISON Scotland (2011) Make a difference: an invitation from UNISON Scotland (PDF). [accessed 16/11/2016]

Author information

This Insight is a collective and collaborative effort involving two Gypsy Travellers and two individuals from a social work background. The attached artwork is by Shamus McPhee.

Acknowledgements

The content of this Insight was reviewed by Helen Allbutt (NHS Education for Scotland), Trisha Hall (Scottish Association of Social Workers), Neil Macleod (Scottish Social Services Council), Judith Okely (Hull University), Neil Quinn (University of Strathclyde), a social work practitioner and colleagues from Scottish Government. Comments represent the views of reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of their organisations. Iriss would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time to reflect and comment on this publication.

This Insight was produced in partnership with SASW. Thanks also to MECOPP for permission to use their Self-Directed Support diagrams.