Introduction

This summary explores the involvement of service users in quality assurance and service evaluation processes. It explores the evidence around what has worked and has not worked, what benefits can be achieved from user involvement in data collection and what can be learned from previous examples.

About the evidence presented below

We drew on a wide range of evidence, including academic research in the fields of health, social care and education in relevant databases (e.g. ASSIA, ProQuest Public Health, SCIE Social Care Online, Social Services Abstracts) and recommendations from specialist organisations (e.g. Care Inspectorate, Evaluation Support Scotland, NHS INVOLVE and SSSC). We searched the academic databases, Google Scholar, search engines and key websites using a broad range of terms including variations on concepts including action research, collaborative assessment, evaluation, consumer participation, co-research, emancipatory research methodology, patient and public involvement (PPI), patient and service user engagement (PSUE), participatory research, peer interviewer, user interviewer, user involvement, and user participation.

Accessing resources

We have provided links to the materials referenced in the summary. Some of these materials are published in academic journals and are only available with a subscription through the The Knowledge Network with an NHSScotland OpenAthens username. The Knowledge Network offers accounts to everyone who helps provide health and social care in Scotland in conjunction with the NHS and Scottish Local Authorities, including many in the third and independent sectors. You can register here. Where resources are identified as ‘available through document delivery’, these have been provided to the original enquirer and may be requested through NHS Scotland’s fetch item service (subject to eligibility).

Where possible we identify where evidence is published Open Access, which means the author has chosen to publish their work in a way that makes it freely available to the public. Some are identified as author repository copies, manuscripts, or other copies, which means the author has made a version of the otherwise paywalled publication available to the public. Other referenced sources are pdfs and websites that are available publicly.

Background

In a social care context, quality assurance can be understood in different but related ways that generally refer to ensuring that services are delivered to a high standard and that good outcomes for service users are ensured. In validation inspections, the Care Inspectorate looks at providers’ quality assurance systems and “how they monitor and ensure good outcomes for people”. The Nursing and Midwifery Council states that “[q]uality assurance makes sure that education programmes meet our standards and that risks are managed effectively”. Quality assurance processes may support continuous improvement in service delivery and identify possible development opportunities (Turning Point Scotland 2011). The National Council for Voluntary Organisations (NCVO) has designed a Practical Quality Assurance System for Small Organisations (PQASSO) quality assurance system to help organisations run “more effectively and efficiently”. Within their system of quality assurance, they include sound governance practices, financial and risk management procedures, and a robust system for measuring outcomes.

Much of the evidence in this Outline is drawn from health literature, because patient involvement in research and service evaluation has an established history. Chew-Graham (2016) suggests that from a health perspective, patients or service users can be involved in research in three ways, which are not mutually exclusive:

- Consultation: The study is researcher-led but consultation with patients occurs about one or more elements of research development

- Collaboration: Patients and professionals occupying equal but different roles in all aspects of project work

- Patient/service user-led: Patients or service users lead research design and implementation of the research

This review focuses on service user involvement in data collection, which falls into categories two and three.

Turning Point Scotland (2011) Good practice guide: service user involvement (pdf)

Turning Point Scotland identify benefits to both individuals and services when a good model of service user involvement is apparent within a service:

- It promotes strong person centred values i.e. equality, dignity, respect, choice

- Individuals are offered an opportunity to share knowledge and expertise

- Individuals can develop new skills, gain confidence and self-esteem

- Discrimination and stigma can be challenged

- It can inform campaigning issues

- It helps services to focus on continuous improvement

- It helps deliver positive outcomes for people who use services

- It helps to meet requirements set out by the Care Commission and contract monitors

They provide a list of advantages around service user involvement and considerations that should be made to ensure it is done well:

| Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Involving service users can be empowering for them | Service users may not wish to be involved |

| It’s a way of giving service users an opportunity to learn new skills and build confidence | A lot of time and commitment can be required to involve service users |

| Services learn how to improve the quality and effectiveness of their provision | Be careful of being tokenistic |

| Involvement makes decision-making more open and democratic | More than one method of involvement will probably be needed to give the full picture |

| It challenges stigma and myths by improving perceptions of service users | Service users with literacy issues may avoid being involved |

| It may improve the reputation and credibility of the service | Some methods of involvement can be costly |

| It enables diversity in experience and opinion to influence decision making | Services should be open to unexpected outcomes from service user involvement activities |

| It helps to create a sense of ownership in people who access services | Careful planning of the involvement process is required |

| It sends a strong message about an organisation’s commitment to service users | There can be potential for misrepresenting service user views |

| It can help service users to build social networks | Service users should always be given feedback on the results of their involvement |

| Volunteer opportunities may emerge from involvement | Training may be needed before service users can be fully involved |

| The skills and confidence gained may improve employability levels | Try to ensure that it is not always the same service users who take lead roles in involvement activities |

| It helps create a partnership between staff and service users |

Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC) (no date) Quality Assurance (website)

SSSC highlights the principles underpinning the quality assurance and enhancement responsibilities in Scottish social care, which includes user involvement:

- Avoid duplication

- Take account of existing internal and external quality arrangements

- Are evidence based

- Based on principles of equal opportunity

- Allow the SSSC to be assured that the provision is of sufficient quality

- Promote continuous improvement in line with expectations of quality enhancement

- Actively involve employers, students, people who use services and carers in the process of course delivery and quality enhancement [our italics]

- Are consistent with the SSSC Codes of Practice for Social Service Workers and Employers of Social Service Workers

Evaluation Support Scotland (2015) Why bother involving people in evaluation? Beyond feedback - a workbook (pdf)

This workbook is a practical tool to help organisations plan why, when and how to involve the people they work with in evaluation. It includes case studies, recommendations and resources for developing participatory approaches to service evaluation.

This Outline focuses on service user involvement in Step 2 of the workbook - collecting information, specifically where data is collected from the service user by previous service users. ESS state that “there is a range of different degrees to which organisations might involve people they work with in evaluation”. In their description of greater involvement, people may be involved in doing some evaluation work and controlling the evaluation process.

They highlight core principles based on their experience:

- Make a commitment to sharing power and responsibility

- Respect all diversity

- Enable and support people to participate

- Recognise and make best use of individuals’ experience

- Do no harm (at the very least)

ESS provide recommendations for approaches to service user involvement in evaluation, including:

- Throughout:

- Use inclusive language

- Respect and accommodate individuals’ circumstances

- Be aware that staff could feel threatened by the people they work with becoming more involved in evaluation

- Don’t be afraid to use your professional judgement sometimes – but do think carefully about how and when

- Planning

- Set out clearly why you are asking the people you work with to become involved in evaluation

- Give one person responsibility for managing the process

- Consult on the agenda

- Define clear, meaningful roles for those who are involved

- Allow plenty of time

- Think about other resource implications

- Consider how you are going to recruit participants

- Be clear in advance about how the results will be used

- Think about whether any training/specialist support is needed

- Action

- Give people appropriate information about what is expected of them in advance

- Ensure nice surroundings and provide refreshments

- Consider and clarify decision-making processes early on

- Consider and clarify how any conflicts will be resolved early in the process

- Allow the opportunity for people to express any particular bias which they bring with them

- Agree boundaries and stick to them

- Take time to build trusting relationships

- Use a wide range of tools and methods

- Listen carefully Accept a bit of randomness and anarchy

- Expect power to shift during the process

- End

- Ensure that what is produced fully represents what has been said

- Thank people for being involved

- Keep participants informed

- Review and refine the process of involving the people you work with in evaluation

The report also includes case studies where organisations have involved the people they work with in planning evaluation.

Evidence

Research on service user involvement in evaluation

The following studies provide examples of research around user involvement in data collection for research and/or service evaluation. It must be acknowledged that research indicates a positive bias in publications around patient and public involvement (PPI) in health (Tierney et al. 2016), and that other research around service user involvement in other fields may be similarly biased. Additionally, the question of how service user involvement can affect the quality of knowledge generated by research has been raised (Entwistle 2010). However, the examples provided below may be useful for the specific enquiry this report seeks to support, which focuses on engaging service users in service evaluation, specifically in the data collection process.

Banongo, E et al. (2006) Engaging service users in the evaluation and development of forensic mental health care services: a peer reviewed report to the funders. London, UK: City University London (pdf

This report describes how a group of seven service users of forensic mental health care were recruited to participate as researchers in a service evaluation project. The authors reflect on the lessons learnt about the processes and problems of undertaking such research, in particular the challenges of recruiting service users to be involved and negotiating their participation. (Summary from Involve)

Brett, J et al. (2012) Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expectations, 17(5), pp.637–650 (Open Access)

This systematic review reports the impact of patient and public involvement on health and/or social care research studies. A total of 66 studies reporting the impact of PPI on health and social care research were included. The positive impacts identified enhanced the quality and appropriateness of research. Impacts were reported for all stages of research, including the development of user-focused research objectives, development of user-relevant research questions, development of user-friendly information, questionnaires and interview schedules, more appropriate recruitment strategies for studies, consumer-focused interpretation of data and enhanced implementation and dissemination of study results. Some challenging impacts were also identified. (Author abstract)

Impacts of user involvement in undertaking research identified from studies included in the review included:

- Pragmatic criticism (e.g. identifying cultural issues that should be taken into account)

- Identifying important outcome measures

- Advising on the appropriateness of design from the user perspective

- Adapting language to suit audience (including vocabulary, tone and sensitivity)

- Identifying effective ways of accessing participants

- Assessing appropriateness of research instruments from a community perspective

- Identifying lines of inquiry for interviews and questionnaires not previously considered

- Insights into cultural perspectives of the community

- Deeper and more personal insights gained by user interviewers because of rapport and empathy users developed with participants, putting participants at ease and providing greater understanding of the encounter

- More honest flow of information during interviews

Croker, JC et al. (2017) Is it worth it? Patient and public views on the impact of their involvement in health research and its assessment: a UK‐based qualitative interview study. Health Expectations, 20(3), pp.519–528 (Open Access)

This study explores the views of PPI (patient and public involvement) contributors involved in health research regarding the impact of PPI on research, whether and how it should be assessed. Thirty‐eight PPI contributors involved in health research across the UK were interviewed. The authors identified several impacts of PPI contributors on research, including:

- Shaping initial research questions and ideas

- Choosing outcome measures that are relevant and meaningful to patients

- Ensuring the efficient delivery of research

- Helping to solve ethical dilemmas

- Improving the way information is communicated to patients

- Optimizing the recruitment of participants and their experiences of taking part

- Collecting and analysing research data

- Disseminating research findings to patients and the public

The authors identify several roles of PPI contributors in terms of their ‘added value’:

| Perceived role | Proposed mechanism of impact |

|---|---|

| The expert in lived experience | Through their lived experience of a condition, PPI contributors are able to consider the acceptability and feasibility of research proposals for the target population |

| The creative outsider | PPI contributors bring a fresh perspective from outside the research system, and can help to solve problems by thinking ‘outside the box’ |

| The free challenger | PPI contributors are able to challenge researchers without fear of consequences |

| The bridger | PPI contributors bridge the communication gap between researchers and patients or the public, making research more relevant and accessible |

| The motivator | PPI contributors increase researchers’ motivation/enthusiasm, for example by emphasizing how the research will benefit people |

| The passive presence | PPI contributors can change the way that professionals think just by being present at meetings |

Elliott, E, Watson, AJ and Harries, U (2002) Harnessing expertise: involving peer interviewers in qualitative research with hard-to-reach populations. Health Expectations, 5(2), pp.172–178 (Open Access)

This paper explores a number of key issues relating to the employment of peer interviewers by reflecting on a project designed to explore the views and experiences of parents who use illegal drugs. The project presented the research team with a number of challenges. These included the need to provide ongoing support for the interviewers, a sense of distance felt by the researchers from the raw data they collected, and the difficulties of gaining from the skills and experiences of peer interviewers without exploiting their labour.

The paper also explores the advantages of involving peer interviewers closely in research work and reflects on the nature and boundaries of expert knowledge that can become evident in such collaborations. The need for a certain amount of flexibility over the roles and domains of control that lay experts and researchers traditionally inhabit is suggested. (Author abstract)

Evans, S et al. (2011) Evaluating services in partnership with older people: exploring the role of ‘community researchers’. Working With Older People, 15(1), pp.26-33 (paywalled or author manuscript)

This article is a collaboration between an academic researcher and four older people who worked together on the evaluation of a pilot project in Gloucestershire, with the aim of ‘making care homes part of our community’. Against a background of increasing public participation in research, we explore the role of ‘community researcher’ and the experiences of those involved. The article starts with an overview of policy and practice developments in relation to public engagement in research.

A description is provided of a research project that included recruiting and training ‘community researchers’ to carry out an evaluation of the Partnerships for Older People Project in Gloucestershire. The next section focuses on the experiences of the older people who carried out this role, including some of the benefits and challenges that were encountered. The article concludes with a discussion of the implications for delivering meaningful public engagement in service development and evaluation. (Author abstract)

Froggatt, K et al. (2015) Public involvement in research within care homes: benefits and challenges in the APPROACH study. Health Expectations, 19(6), pp.1336-1345 (Open Access)

Public involvement in research (PIR) can improve research design and recruitment. Less is known about how PIR enhances the experience of participation and enriches the data collection process. In a study to evaluate how UK care homes and primary health-care services achieve integrated working to promote older people’s health, PIR was integrated throughout the research processes. This paper aims to present one way in which PIR has been integrated into the design and delivery of a multisite research study based in care homes. Data collection was undertaken in six care homes in three sites in England. PIR members supported recruitment, resident and staff interviews and participated in data interpretation. Benefits of PIR work were resident engagement that minimized distress and made best use of limited research resources. Challenges concerned communication and scheduling. Researcher support for PIR involvement was resource intensive. (Author abstract)

Godfrey, M (2004) More than 'involvement'. How commissioning user interviewers in the research process begins to change the balance of power. Practice: Social Work In Action, 16(3), pp.223-231 (paywalled

The author undertook a small-scale research study to obtain the views of users, carers and social workers regarding their perceptions of change. He discusses how as part of the research design he worked with a voluntary organisation and commissioned users to interview other users. He examines the advantages of adopting such an approach, and how this experience changed his thinking about user involvement. He suggests that more efforts need to be made if user involvement is going to progress beyond the participation level. He argues that if real change is to take place, the balance of power has to be shifted.

Gomez, RJ and Ryan, TN (2016) Speaking out: youth led research as a methodology used with homeless youth. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 33(2), pp.185–193 (paywalled)

In this study, the authors examine the use of youth led research as a methodology among a population of homeless youth. Peer researchers (n=10) reported on their experience utilizing youth led research methodology. Results indicate that youth led research is a promising methodology for use among homeless youth. Participants reported that the approach positively impacted the quality and quantity of data that could be collected from participants. Further, peer researchers reported individual benefits of feeling that participating in the project mattered, that people listened to them and that they had a voice. (Author abstract)

The authors report several benefits described by participants of being a peer researcher:

- Viewed as empowering and rewarding

- Produced a feeling of hope for the future

- Peer researchers felt listened to and valued

- Felt that their voice mattered

- Perceived that policymakers listened to them and valued their feedback

- Helped them gain a greater sense of empathy for others who have experienced similar challenges

- Felt their participation sparked a desire to continue helping others

- Felt empowered to make a difference in the system by participating in the study

- Motivating to be trusted with someone’s story

Hitchen, SA and Williamson, GR (2015) A stronger voice: action research in mental health services using carers and people with experience as co-researchers. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 28(2), pp.211–222 (Open Access

This paper discusses learning about service-user and carer involvement from an action research (AR) study into self-directed support implementation in one English mental health trust. It explored how patients and carers in eight diagnostic research specialties have been involved in research, their motivations and the impact involvement had on them. Using an online semi-structured questionnaire (143 patient respondents), the authors identified several benefits of involvement in research. 14% of respondents were involved in the collection of data or implementation of intervention.

The authors suggest that participation gave co-researchers a powerful and effective voice in this service redesign. Benefits of patient and public involvement (PPI) included: psychological and social benefits; intellectual benefits; and and improved relationship with illness and crisis. The authors suggest that action research can be a suitable method to enable service users to undertake research, but that guidance and support is required from lead researchers. This approach revealed more authentic research data and required professionals to be more accountable for their perceptions and to make explicit their understandings throughout the study, which enabled more effective working. Concerns raised included tokenistic involvement and whether their contributions had been factored in to the research.

Jørgensen, CR et al. (2017) The impact of using peer interviewers in a study of patient empowerment amongst people in cancer follow-up. Health Expectations, (preview before publication) (Open Access)

This study aims to investigate the impact of involving patient representatives as peer interviewers in a research project on patient empowerment. 18 interviews were carried out as part of the wider study, seven by the academic researcher alone and eleven jointly with a peer interviewer. The interviews were analysed quantitatively and qualitatively to explore potential differences between interviews conducted by the researcher alone and interviews conducted jointly by the researcher and the peer interviewers. A phone evaluation of the peer interviews was carried out with the research participants, and notes were thematically analysed to understand their experiences.

Differences were identified between the academic researcher and the peer interviewers in the types of questions they asked and the degree to which personal narrative was used in the interview. Peer interviewers varied significantly in their approach. Research participants were positive about the experience of being interviewed by a peer interviewer. No firm conclusions could be made about impact on outcomes.

The uniqueness and complexity of qualitative interviews made it difficult to provide any firm conclusions about the impact of having peer interviewers on the research outcomes, and the benefits identified from the analysis mostly related to the process of the interviews. Benefits from using peer interviewers need to be considered alongside relevant ethical considerations, and available resources for training and support. (Author abstract)

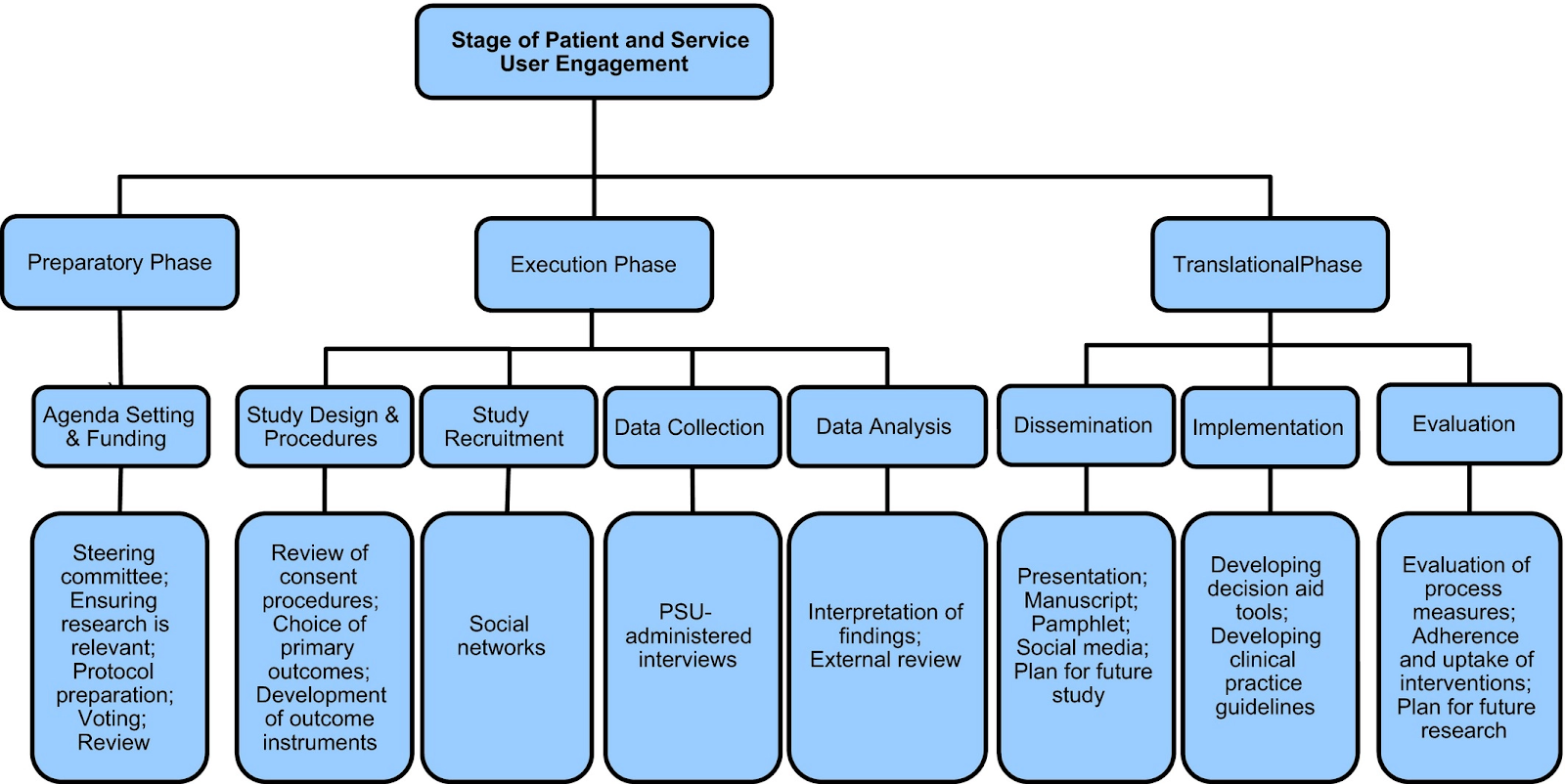

Shippee, ND et al. (2015) Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expectations, 18(5), pp.1151–1166 (Open Access)

This systematic review uses an environmental scan methodology to develop an evidence-based framework for patient and service user engagement (PSUE). The authors identify two aims of efforts to increase PSUE:

- A moral/ethical drive to empower lay participants in an otherwise expert‐dominated endeavour and ensure civically responsible research

- ‘Consequentialist’ reasoning for optimizing the validity, design, applicability or dissemination of the research itself and the effectiveness of resulting interventions

The authors took 37 sources describing frameworks/conceptualisations of PSUE and built a synthesised framework comprised of three broad phases of research (preparatory, execution and translational phases) and the specific stages within them to illustrate the ways PSUE can be operationalised.

The authors identified several benefits of PSUE described within the research papers they analysed, including that PSUE “allowed PSURs who were uncomfortable with questionnaires to participate – for example, engaging key PSURs as trained research assistants in collecting and analysing data.

Truman, C and Raine, P (2001) Involving users in evaluation: the social relations of user participation in health research. Critical Public Health, 11(3), pp.215-229 (paywalled)

This paper examines the role of user involvement in evaluative research within the provision of an evidence base related to practice development. It identifies factors that may facilitate or inhibit user involvement and participation in evaluative research. The authors suggest that the creation of evidence in health research is shaped by the social relations of the research process as well as by the methodologies used. The authors explore users’ perceptions of their involvement in research design. They observed: “The high level of user involvement and positive environment that characterized the facility meant that many of the users saw involvement in the research as a way of giving something back to the service”. Challenges for participation included:

- Participating in group work

- Timing of focus groups

- Side-effects of medication affecting concentration

- Fluctuations in mental health symptoms

Approaches to addressing these challenges included fitting the research methodology around service user needs and constraints and enabling service users to engage on their own terms. In most instances this involved one to one interviews as a research method, with users deciding the time and venue. Building trust was identified as a crucial component, as was enabling the user interviewer to pursue their own interests and motivations for being involved in data collection.

van der Ham, AJ et al. (2014) Facilitators and barriers to service user involvement in mental health guidelines: lessons from the Netherlands. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(6), pp.712–723 (paywalled or author copy)

This study explores service user involvement in the development of multi- disciplinary mental health guidelines in the Netherlands. It uses document analysis, interviews and observations to identify how multidisciplinary mental health guidelines have taken service user perspectives into account and highlights the themes and associated barriers and facilitators of service user involvement within these guidelines. The themes include issues relating to the process of service user involvement. The authors suggest the insights they provide into facilitators and barriers “will aid in the planning, monitoring and evaluation of service user involvement”.

Whitley, R (2005) Letters: client involvement in services research. Psychiatric Services, 56(10), pp.1315-1315 (Open Access)

The author of this letter shares lessons learned from his experience as an academic consultant to a mental health day service, where he used collaborative evaluation with clients to inform future planning for mental health services. He reports on his experiences, describing how clients made contributions to the successful development of the evaluation:

- Questionnaire development

- Ensuring that it covered clients' concerns

- Prevented bias toward the provider's perspective

- Identifying modes of data collection (anonymous "suggestion box" and focus groups)

- Suggestion box allowed clients to comment anonymously in their own time

- Suggestion box and focus groups allowed clients who were uncomfortable with the questionnaire to participate

- Focus group provided "safety in numbers" - being able to voice concerns in the presence of fellow clients

- Training key clients as research assistants

- Clients particularly sensitive and skillful in helping other clients complete the questionnaire

- Increased response rate

- Encouraged more open and honest responses from clients

- Involvement in data analysis

- Increase the validity of findings through process of reaching consensus on emerging conclusions and their significance

Whitley reports that some clients, even some with serious mental illnesses, were “quite capable of quickly understanding the scientific basis of research” and that several participants were highly qualified prior to needing support from the service due to mental illness. Other clients had less understanding of the scientific basis of research, which he suggests may mean some time may need to be spent supporting participants to understand methodologic issues.

Disadvantages identified included:

- Greater resources in terms of time, labour, and finances

- Endpoint of service user involvement must be managed carefully to ensure ambiguity and conflict at the end of the project is avoided

Examples of and guidelines for service user involvement in evaluation

Gillard, S et al. (2012) Patient and public involvement in the coproduction of knowledge: reflection on the analysis of qualitative data in a mental health study. Qualitative Health Research, 22(8), pp.1126–1137 (paywalled or author copy)

The authors describe a process of qualitative data analysis in a mental health research project with a high level of mental health service user and carer involvement, and reflect critically on how they produced their findings. They discuss how patient and public involvement led to the discovery of complex findings that would otherwise have been missing and describe how this was achieved through the coproduction of knowledge and methodological flexibility, and deliberate and transparent reflection throughout the process.

Loughran, H and McCann, ME (2015) Employing community participative research methods to advance service user collaboration in social work research. The British Journal of Social Work, 45(2), pp.705–723 (paywalled)

This research sought to engage service users as both participants and as co-researchers in a study of the experience of drug problems in three Dublin communities. The work adopted a community participatory methodology. Reflecting on their experiences, the authors describe how meaningful collaboration demanded the added task of training members of the community in research methods, including data collection and analysis. Other points include that “supporting community researchers from the grass roots strengthened the study but was time and resource intensive”, and that “community researchers struggled to appreciate that their viewpoint was valuable and valid”. The authors discuss the benefits of community-based research, including that “some of the most insightful data gathered came from local contacts and community sources and university researchers would not have had access to this without the community researchers”, and that “local knowledge and being known locally were parallel aspects of successful recruitment of participants”.

National Institute for Health Research (no date) Involving users in the research process: a ‘how to’ guide for researchers (pdf)

National Institute for Health Research suggest some considerations when involving service users in data collection in the context of formal research:

- Users will need to understand how to collect data. This will require training and/or a previous knowledge of conducting research.

- This will also require researchers to acknowledge users’ involvement as a member of the research team.

- Seek advice from the BRC User Involvement Manager (see page 14 for contact details) regarding the protocols associated with involving users in data collection.

They also make suggestions about how to involve users:

- Seek the opinion of users already involved in the project as members of the steering group or advisory panel, about the appropriateness of having users collecting data.

- Ask for volunteers from those already involved in the project steering group.

- Recruit specifically for users interested in undertaking data collection. This allows you to stipulate certain requirements and skills for the role.

- Liaise with the BRC User Involvement Manager (see page 14 for contact details) about training for users in data collection techniques.

Rethink (2009) Getting back into the world: reflections on lived experiences of recovery. AstraZeneca (pdf)

This report from a study involving in-depth interviews with 48 people describes what made mental health recovery possible given particular circumstances and conditions.

Seven involvement researchers with personal experience of mental illness and psychiatric treatment led the interviews and the write-up of findings. The research process involved seven stages:

- Group construction of themes and structure for the interview guide

- Reflexive exchanges through dialogue about experiences during interviews

- Involvement researchers writing post-interview personal reflexive notes

- Thematic analysis of interviews drawing on the reflexive notes

- Group construction of analytic framework identifying key themes

- Involvement researchers identifying data for themes and including personal reflections

- Group validation and edit of collated write-up of themes

This report provides information about the recruitment and training of the involvement researchers.

Rethink (2010) Recovery insights: learning from lived experience. AstraZeneca (pdf)

This report is about the different ways in which people live with and recover from persistent or recurring mental health problems. It draws on 55 people’s personal experience of mental illness and psychiatric treatment. It took a participatory approach to the research:

Seven people with personal experience of mental illness and psychiatric treatment worked as researchers on this project. They conducted semi-structured interviews with 48 people in order to gain a deep understanding of people’s beliefs, attitudes and lives in relation to recovery. A particular quality of this study was the researchers’ use of personal experience throughout the research. A detailed account of the methods can be found in the full report

Training in research methods was delivered by a mental health survivor research consultant and support during data collection and analysis was provided by the Rethink research team. In the report the researchers provide a reflection on their experiences of taking part in the study, which included interview design, analysis, write-up and dissemination of findings.

Suggestions for carrying out similar work are provided, including recommendations for payment, facilitation, expectations around communication, skills support, fair allocation of work tasks, considering the abilities of user researchers, stress in the research process, supervision and support, and confidentiality.

Staley, K (2013) A series of case studies illustrating the impact of service user and carer involvement on research. National Institute for Health Research (pdf)

This report includes three case studies (1-3) in which service users and carers were involved in the data collection element of research. The case studies report on how service users and carers were involved, the impact of involving service users and carers in the different stages of research, and lessons learned.

Turning Point Scotland (2011) Good practice guide: service user involvement (pdf)

Turning Point Scotland report that they involve people in audit and appraisal of services:

A combination of internal self-assessment and audit processes, and inspection by external agencies helps services to focus on continuous improvement in service delivery. Additionally a staff appraisal system offers the opportunity for staff and managers to consider how staff performance affects the quality of service delivery and to identify possible development opportunities. It is important that the people who use services are given the opportunity to play a part in assessing the quality of service delivery, and to give constructive feedback to staff on their performance.

Existing good practice within services includes:

Substance misuse services:

- Care Commission inspectors speak to service users and occasionally sit in on group work sessions to allow informal discussion with service users about the service provided

- Service users have an opportunity to input to Impaqt self assessment tool

- A service user involvement log is in each service users file to be seen by auditors and inspectors

References

- Banongo, E et al. (2006) Engaging service users in the evaluation and development of forensic mental health care services: a peer reviewed report to the funders. London, UK: City University London (pdf)

- Brett, J et al. (2012) Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expectations, 17(5), pp.637–650 (Open Access)

- Chew-Graham, C (2016) Positive reporting? Is there a bias is reporting of patient and public involvement and engagement? Health Expectations, 19(3), pp.499-500 (Open Access)

- Croker, JC et al. (2017) Is it worth it? Patient and public views on the impact of their involvement in health research and its assessment: a UK‐based qualitative interview study. Health Expectations, 20(3), pp.519–528 (Open Access)

- Elliott, E, Watson, AJ and Harries, U (2002) Harnessing expertise: involving peer interviewers in qualitative research with hard-to-reach populations. Health Expectations, 5(2), pp.172–178 (Open Access)

- Entwistle, V (2010) Involving service users in qualitative analysis: approaches and assessment. Health Expectations, 13(2), pp.111–112 (Open Access)

- Evaluation Support Scotland (2015) Why bother involving people in evaluation? Beyond feedback - a workbook (pdf)

- Evans, S et al. (2011) Evaluating services in partnership with older people: exploring the role of ‘community researchers’. Working With Older People, 15(1), pp.26-33 (paywalled or author manuscript)

- Froggatt, K et al. (2015) Public involvement in research within care homes: benefits and challenges in the APPROACH study. Health Expectations, 19(6), pp.1336-1345 (Open Access)

- Gillard, S et al. (2016) Evaluating the Prosper peer-led peer support network: a participatory, coproduced evaluation. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 20(2), pp.80-91 (paywalled or author manuscript)

- Godfrey, M (2004) More than 'involvement'. How commissioning user interviewers in the research process begins to change the balance of power. Practice: Social Work In Action, 16(3), pp.223-231 (paywalled)

- Gomez, RJ and Ryan, TN (2016) Speaking out: youth led research as a methodology used with homeless youth. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 33(2), pp.185–193 (paywalled)

- Hitchen, SA and Williamson, GR (2015) A stronger voice: action research in mental health services using carers and people with experience as co-researchers. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 28(2), pp.211–222 (Open Access)

- Jørgensen, CR et al. (2017) The impact of using peer interviewers in a study of patient empowerment amongst people in cancer follow-up. Health Expectations, (preview before publication) (Open Access)

- Loughran, H and McCann, ME (2015) Employing community participative research methods to advance service user collaboration in social work research. The British Journal of Social Work, 45(2), pp.705–723 (paywalled)

- National Council for Voluntary Organisations (no date) PQASSO (website)

- National Institute for Health Research (no date) Involving users in the research process: a ‘how to’ guide for researchers (pdf)

- Nursing and Midwifery Council (2017) Quality assurance of nursing and midwifery education: annual report 2017-17 (pdf)

- Rethink (2009) Getting back into the world: reflections on lived experiences of recovery. AstraZeneca (pdf)

- Rethink (2010) Recovery insights: learning from lived experience. AstraZeneca (pdf)

- Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC) (no date) Quality Assurance (website)

- Shippee, ND et al. (2015) Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expectations, 18(5), pp.1151–1166 (Open Access)

- Staley, K (2013) A series of case studies illustrating the impact of service user and carer involvement on research. National Institute for Health Research (pdf)

- Tierney, E et al. (2016) A critical analysis of the implementation of service user involvement in primary care research and health service development using normalization process theory. Health Expectations, 19(3), pp.501-515 (Open Access)

- Truman, C and Raine, P (2001) Involving users in evaluation: the social relations of user participation in health research. Critical Public Health, 11(3), pp.215-229 (paywalled)

Turning Point Scotland (2011) Good practice guide: service user involvement (pdf)

van der Ham, AJ et al. (2014) Facilitators and barriers to service user involvement in mental health guidelines: lessons from the Netherlands. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(6), pp.712–723 (paywalled or author copy)

Whitley, R (2005) Letters: client involvement in services research. Psychiatric Services, 56(10), pp.1315-1315 (Open Access)