Key points

- Participation is a priority in many health and social care policies which encourages practice to encompass consultation, engagement, co-design and co-production

- There is evidence that projects and services which use co-production methods, such as co-delivery of services, are beneficial for people

- People who use services make valuable contributions to the design and delivery of health and social care

- There is still a need for more evidence on costs savings, social return on investment and impact on health and wellbeing, developed and delivered through participation

- The long-term effects of participation, particularly indirect effects, can be difficult to measure and attribute to participation approaches

- Key implications for practice: participation approaches such as co-design and delivery of training and more formalised roles must be prioritised to encourage an assets-based approach in everyday practice

- Evaluation of participation should consider the impact on the people who use services which have been developed through participation

Introduction

Participation is an umbrella term for any activity where the general public are involved in developing health and social care services (McGrow, 2011). In their participation toolkit (2014), the Scottish Health Council define participation as:

“…involving people in: decisions about their own care, shaping and influencing service provisions as communities of interest or geography and, working in partnership with service providers.”

This definition of participation recognises the valuable contribution people can make in shaping services beyond simply consuming them. It also highlights the different systematic levels at which participation can occur: at the individual level, the service level, and the strategic level where the public are involved in changing a health system or policy (Morton and Paice, 2016).

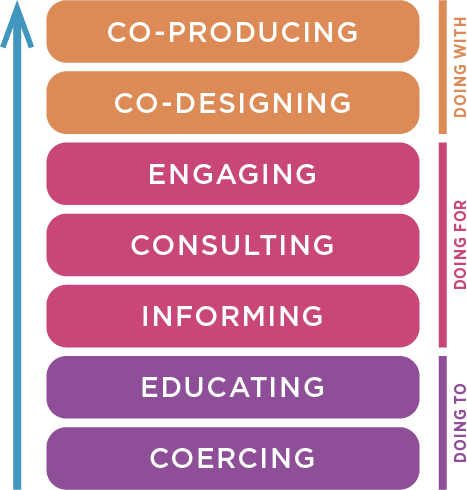

The use of the term ‘participation’ throughout this report refers to instances where people who use services (PWUS), carers and relatives of those who use services and the general public, have been involved in developing health and social care at service and strategic levels. The impact of participation at the individual level, such as shared decision-making, will not be discussed here. The services reviewed include health, primary social care and the third sector. Participation can be conceptualised as seven points on a ladder (Slay and Stephens, 2013), as demonstrated in Figure 1.

Engagement and consultation involves health professionals using feedback from the public and PWUS to improve services. Co-designing involves the public working with professionals to design services or procedures while professionals deliver it. Co-production is placed at the top level of the NEF model as shown, as it entails service users and communities holding equal power with service providers, where they are involved in producing a service or product.

The purpose of participation is to improve the health, wellbeing and lives of PWUS, relatives and carers, and the wider public through empowerment (Ocloo and Matthews, 2016). Despite this, there is a continuation of tokenistic or paternalistic methods. For example, simply gathering feedback on services with surveys which have been produced by health professionals limits the opportunity for dialogue between PWUS and providers and for PWUS to influence real change (Ocloo and Matthews, 2016).

Policy context

It is clear that participation is a priority for the delivery of high-quality health and social services. Policy such as the Health and Social Care Delivery Plan (Scottish Government, 2016) and 2020 vision set out for health and social care in Scotland (Scottish Government, 2013) have highlighted the need for participation in health and social care in Scotland. It is now recognised within policy that participation must be an essential part of social care.

One of the four main principles in the Christie commission (2011) is that public services must facilitate the empowerment of individuals and the wider community by involving them in the design and delivery of care. Participation in public services will also facilitate the other three principles of partnership, prevention and performance (Christie commission, 2011).

The Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014 highlighted the need for services to be person-centred with the community influencing the planning and delivery of services. In addition, the National Health and Social Workforce Plan, the Scottish Social Service Council (SSSC) codes of practice, and the Community Empowerment Act (2015) all state that there must be systems in place to get feedback from PWUS, their carers and families, and the public, to support the design and delivery of high-quality public services.

Evidence and focus

Most of the literature consists of surveys and qualitative reports of PWUS and staff experiences of engaging in the process of participation and descriptions of what or how things have changed (Crawford and colleagues, 2002; Simpson and House, 2002; Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers, 2014). There are also many case studies. However, much of this evidence tends to answer questions such as: are services engaging in participation? And if so, how? Questions such as: what is participation doing for the PWUS, their relatives and carers? are reported less often. More specifically, there is a lack of evidence of the impact of participation on outcomes such as cost savings, including social return on investment (SROI) and improved mental wellbeing of PWUS, developed and delivered through participation. This Insight will focus on these aspects as opposed to normative arguments (eg ethical considerations, public accountability) alone.

Grey and academic literature was searched but the majority of evidence reviewed here is academic as it was more likely to report health and social outcomes for PWUS. While the majority of evidence which met the criteria is from health services, it is anticipated that social care service providers can learn from this.

Consultation and engagement

Community interventions which have been designed based on consultation and engagement with the public and PWUS have shown signs that communities and individuals are more empowered. A community engagement project called Well London (Phillips and colleagues, 2014) measured community-led health goals about fruit and vegetable intake, exercise and wellbeing activities. The project found that unhealthy food consumption was lower in intervention neighbourhoods compared to neighbourhoods which had not engaged in the interventions.

Another project encouraged the self-management of mental wellbeing through social prescribing which were designed in consultation with the community and PWUS. Social prescribing involves referral to community services which provide social support through activities such as art and crafts. Referral to social prescribing activities led to improved mental wellbeing and confidence to manage compared to before referral. There was a 38% and 54% reduction in symptoms of depression and anxiety respectively with statistically significant reductions in those who scored within the clinical range of depression (17%) and anxiety (16%).

A large study which drew together evidence from many studies of engagement and consultation concluded that there was good evidence that community engagement interventions are effective at improving confidence, health behaviours, health consequences and perceived social support in both individuals who engaged and communities as a whole (O’Mara-Eves and colleagues, 2013). Engagement and consultation have also resulted in an increased feeling of community cohesiveness (Phillips and colleagues, 2014). Meanwhile, an engagement project led by East Dunbartonshire Council where providers and the public participated in asset mapping resulted in 50% increased awareness of mental health and wellbeing provision in the area (Iriss, 2012).

Co-design

There is an association between patients and the community acting as co-designers and improvements in patients’ self-management and physical and mental health. A co-designed tool to improve self-management of a chronic lung condition had a mixed impact on management (Roberts and colleagues, 2015). With use of the tool, GPs were more likely to provide a diagnosis, refer the patient for rehabilitation and provide a self-management plan, but were not more likely to provide smoking cessation advice or patient reviews. In addition, a mental health self-management programme, co-designed by clinicians and people with lived experience of mental ill-health, showed significant decreases in depression and anxiety at six month follow-up, and 39% of PWUS were considered recovered after engaging in the course (Turner and colleagues, 2015). Health status, quality of life and self-management skills were significantly improved at follow-up compared with prior to completing the course.

There is some evidence that co-design can affect reductions in unnecessary use of services. The establishment of a group of patients, carers and the community working with health professionals to plan and design better integration of health and social care (Vackerberg, 2013) led to reductions in the number of unnecessary hospital days (1,113 in 1999 to 62 in 2011) and admissions (9,300 in 1998 to 6500 in 2013). The number of hospital days for heart patients also fell by 1,000 within two years. Waiting times to see neurologists and gastroenterologists, previously 62 days and 48 days respectively, were both reduced to 14 days in 2003.

Services have used experience-based co-design (EBCD) methods to improve patient experience where experiences of services are gathered from in-depth interviews from patients, carers and staff, and which are translated into quality improvement goals by service users and providers. EBCD was used with patients and staff of the Betts psychiatric ward working together to improve the service for both patients and staff (Springham and Roberts, 2015). This resulted in the number of formal complaints falling from 13 complaints occurring over a 19-month period to no complaints in the 23 months following EBCD. While this is a positive result, EBCD requires a continuous commitment from managers, staff and service users, and a continuous improvement process to be successful. If staff turnover and burnout are high within services, then this may be more difficult. A co-design project in a Norway mental health hospital which established a patient education centre, employed a part-time service user expert, and aimed to improve the information centre and organisational culture, led to no changes in patient experience and satisfaction. This may have resulted from inappropriate implementation methods (Rise and Steinsbekk, 2015).

Co-production

Improvements in health and wellbeing have been found when care is delivered by PWUS and the community. An evaluation of a peer support self-management programme for people living with hepatitis C and HIV found that 49% of participants experienced better emotional wellbeing prior to using the self-management programme, and there was a 34% reduction in use of NHS services (Nesta, 2012). In a report evaluating the impact of volunteers on a variety of outcomes in the Helping in Hospitals’ initiative across several NHS trusts (Babudu, Trevethick and Späth, 2016), there was some evidence that mental wellbeing appeared to improve in patients – two trusts reported significant positive change in anxiety, while three trusts reported improved mood of patients. Four of the six hospitals which measured nutrition levels found that there was a significant positive change in nutrition levels with the introduction of volunteers in the wards. One hospital reported a significant positive change in hydration levels in patients.

The provision of peer support networks has led to reductions in the use of formal services. The benefit of a Service User Network (SUN) was compared to formal therapy (Jones, Juett and Hill, 2012). There was a significant reduction in admittance to a psychiatric ward between six months pre and post joining SUN, suggesting a positive impact. While there was no significant difference in re-admittance at six months post-intervention between SUN and those receiving therapy, there was a significant difference at 12 months post-intervention. This suggests that SUN was more effective than therapy over the long-term for reducing admittance to a psychiatric ward.

An evaluation of a peer support programme for addiction, called Evie, delivered through text messages in East Lancashire and West Kent found that of 169 service users using the Evie service in East Lancashire, there were no re-presentation to structured treatment within a six-month period. In West Kent, only 4% re-presented to structured treatment (Graham and Rutherford, 2016). A study of peer support for breastfeeding found that the intervention group had reduced visits to primary care and the emergency room, and had significantly fewer prescriptions issued (O’Mara-Eves and colleagues, 2013). The British Lung Foundation initiated a peer support programme which resulted in participants feeling more confident and in control of managing their condition, in addition to 42% and 57% decreases in both unplanned GP visits and hospital admissions respectively (Graham and Rutherford, 2016).

Cost savings of using co-production has been estimated in both health and social care settings. Volunteers have found to contribute 79,128 hours of service with £58,000 a year spent on volunteers (Naylor and colleagues, 2013). It was estimated that for every £1 spent on volunteers’ training and supervision, NHS trusts can expect a return of about £11 (Galea, and colleagues, 2013; Naylor and colleagues, 2013). Kings College Hospital Trust found there was an estimated SROI, depending on volunteer hours, of between £5.40 and £16.40 for every £1 spent (Fitzsimons and colleagues, 2014). The Expert Patient Programme (EPP) is a six-session self-management programme delivered by people with lived experience of a chronic health condition (O’Mara-Eves and colleagues, 2013). Research found that the EPP group incurred costs of £1,912 per patient over six months compared with £1,939 per patient for the control group. While this saving seems small, it meets the £20,000 threshold per quality-adjusted-life-year (QALY) gained criteria for probability of cost-effectiveness.

Evidence suggests that hospital stays decrease with the use of co-production in social care settings, and this has been linked to cost savings. There have been reductions reported between 27% and 29% in use of A&E (SCIE, 2017 and Nesta, 2012 respectively), as well as 37% reduction in non-elective admissions (SCIE, 2017). There has also been a 47% reduction in overnight hospital stays reported for projects where volunteers support capacity and network building for older people, and where older people volunteered to work in partnership with health boards and third sector organisations to develop services for older people (Nesta, 2012). For every £1 spent, it was estimated that £1.60 was saved from the reduction in bed use alone. It was also reported that there would be a saving of £300 per person per year based on improved quality of life following decreases in anxiety and depression (Nesta, 2012). Reductions in social care costs of 8% have also been reported from volunteer projects (Nesta, 2012). In addition, The Shared Lives initiative which places vulnerable adults with mental health issues or learning disabilities with volunteers in the community for permanent or short-term care led to between £8,000 and £26,000 net savings per year compared with institutional care (Clarence and Gabriel, 2014).

Co-design and co-production approaches

There is some evidence that the involvement of PWUS and the community on both the design and delivery of services has an impact on health outcomes. An initiative where a group of patients, doctors, carers, and representatives of the community (called an AF4Q group) commission, design and deliver services was compared to a national sample on some health outcomes. When comparing patients of AF4Q communities to a national sample, it found that 12 of 14 AF4Q communities showed some improvement in diabetes indicators at six-month follow-up (McHugh and colleagues, 2016). Another study reported the effectiveness of a computerised cognitive behavioural therapy programme (CCBT) commissioned by a user-led mental health service (Cavanagh, Seccombe and Lidbetter, 2011). There was a 53.6% reduction in patients who met criteria for depression or anxiety after taking part in the CCBT.

A study compared a group who used either a combined approach with consumer-operated support service (COSS) and community mental health services (CMHS) or a group who used CMHS alone (Segal, Silverman and Temkin, 2011). Over eight months, participants in the combined group experienced decreases in confidence and social integration with slight increases in personal empowerment. Those in the CMHS-only condition experienced enhanced confidence, personal empowerment and social integration. Participants who engaged in a co-designed and co-delivered peer support network for mothers reported significantly lower mental distress eight weeks after beginning the intervention, as well as some improved feelings around social capital (Bolton and colleagues, 2015).

Involving PWUS and carers in the design and delivery of training can improve how health and social care providers relate to service users. A co-designed and co-delivered course to train community mental health professionals in involving PWUS and carers in care planning led to those who engaged in the course reporting that the training helped them improve understanding, develop skills and increase confidence in involving service users and carers (Grundy and colleagues, 2017). Another study where PWUS led and co-delivered training about substance misuse to health professionals resulted in a reported increase in understanding, which was significantly higher than prior to the training and when compared to clinician-led training (Roussey and colleagues, 2015). User involvement in social work education is mandatory where those who have used services discuss their experiences and are involved in role-play with social work trainees (Iriss, 2018). In one case study, it was reported that 93% of health and social care students felt that engaging with people with experience of social care helped them learn. 72% either agreed or strongly agreed that their knowledge of health and social care had improved, and just as many students felt that the experience helped them consolidate previous learning.

Implications for practice

Working with PWUS can increase understanding of social care providers as can be seen in the evidence on PWUS co-designing and delivering training to health and social care students and professionals. This could produce workers who recognise the assets of people who use services, and engage in more empowering relations with clients. The more empowered people are who use services, the more able they will be to self-manage and reduce the use of primary services.

It is recommended that:

- Co-production and co-design are prioritised because greater sharing of power between PWUS and social care professionals may lead to further empowerment of PWUS and the wider public

- PWUS are involved in the design and delivery of training of all social care staff

- There should be further provision of formalised roles for people with experience of using services such as peer support workers

- Prior to commencing the participation process, the aims of participation are considered and included in evaluating and measuring the success of participation in services, and that these are measured over the longer term

Conclusion

The impact of using participation approaches within health and social care was positive overall where most reported either health or economic outcomes, and only a small number of projects reported social outcomes. Generally, it appears that co-production methods such as peer support, volunteering and co-delivery of services were beneficial, particularly for more efficient use of services and cost savings. Furthermore, most of the evidence available for the impact of participation is in the health sector.

It is important to remember that the quality of some of the available evidence is poor due to small samples, poor reporting and use of non-validated outcome measures. The long-term effects of participation, particularly indirect effects, can be difficult to measure and to attribute to participation approaches. While there is a lot of participation work being carried out in third sector social care organisations, evaluations or case studies of this work rarely measure whether the aims of participation are being met as stated within policy such as the Christie commission (2011). That is, whether participation leads to empowerment and improved health and wellbeing of PWUS, relatives, carers and the wider public (Ocloo and Matthews, 2016).

References

- Babudu P, Trevethick E and Späth R (2016) Measuring the impact of helping in hospitals: a final evaluation report. London: The Social Innovation Partnership

- Bolton M, Moore I, Ferreira A et al (2015) Community organizing and community health: piloting an innovative approach to community engagement applied to an early intervention project in south London. Journal of Public Health, 38, 1, 115-121

- Cavanagh K, Seccombe N and Lidbetter N (2011) The implementation of computerized cognitive behavioural therapies in a service user-led, third sector self help clinic. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 39, 4, 427-42

- Christie C (2011) Commission on the future delivery of public services. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government

- Clarence E and Gabriel M (2014) People helping people: the future of public services. London: Nesta

- Crawford MJ, Rutter D, Manley C et al (2002) Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. BMJ, 325, 1263.

- Fitzsimons B, Goodrich J, Bennett L et al (2014) Evaluation of King’s College Hospital volunteering service. London: King’s Fund

- Galea A, Naylor C, Buck D et al (2013) Volunteering in acute trusts in England: understanding the scale and impact. London: King’s Fund

- Graham JT and Rutherford K (2016) The power of peer support: what we have learned from the Centre of Social Action Innovation Fund. London: Nesta

- Grundy AC, Walker L, Meade OL et al (2017) Evaluation of a co-delivered training package for community mental health professionals on service user and carer involved care planning. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 24, 358-366

- Iriss (2012) Using an assets approach for positive mental health and well-being: an Iriss and East Dunbartonshire Council project. Glasgow: Iriss

- Iriss (2018) Inter-professional education within integrated services: user involvement in social work education. Glasgow: Iriss

- Jones B, Juett G and Hill N (2012) A two-model integrated personality disorder service: effect on bed use. Psychiatrist, 36, 8, 293-298

- McGrow G (2011) A literature review of the benefits of participation in the context of NHS Scotland’s Healthcare Quality Strategy. Edinburgh: Scottish Health Council

- McHugh M, Harvey JB, Kang R et al (2016) Community-level quality improvement and the patient experience for chronic illness care. Health Services Research, 51, 1, 76-97

- Morton L, Ferguson M and Baty F (2015) Improving wellbeing and self-efficacy by social prescription. Public Health, 129, 3, 286-9

- Morton M and Paice E (2016) Co-production at the strategic level: co-designing an integrated care system with lay partners in North West London, England. International Journal of Integrated Care, 16, 2, 2, 1–4

- Naylor C, Mundle C, Weaks L et al (2013) Volunteering in health and social care: securing a sustainable future. London: King’s Fund

- Nesta (2012) People powered health co-production catalogue. London: Nesta

- NHS Scotland (2013) A route map to the 2020 vision for health and social care. Edinburgh: NHS Scotland

- Ocloo J and Matthews R (2016) From tokenism to empowerment: progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25, 8, 626-632

- O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, McDaid D et al (2013) Community engagement to reduce inequalities in health: a systematic review, meta-analysis and economic analysis. Public Health Research, 1, 4

- Phillips G, Bottomley C, Schmidt E et al (2014) Well London Phase-1: results among adults of a cluster-randomised trial of a community engagement approach to improving health behaviours and mental well-being in deprived inner-city neighbourhoods. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 68, 7, 606-14

- Rise MB and Steinsbekk A (2015) Does implementing a development plan for user participation in a mental hospital change patients' experience? A non-randomized controlled study. Health Expectations, 18, 5, 809-25

- Roberts CM, Gungor G, Parker M et al (2015) Impact of a patient specific co-designed COPD care scorecard on COPD care quality: a quasi-experimental study. NPJ Primary Care Respiratory Medicine, 25, 5

- Roussy V, Thomacos N, Rudd A et al (2015) Enhancing health-care workers' understanding and thinking about people living with co-occurring mental health and substance use issues through consumer-led training. Health Expectations, 2015, 18, 5, 1567-81

- SCIE (2017) Total transformation of care and support. London: SCIE

- Scottish Government (2014) The Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014. Norwich: TSO (The Stationary Office)

- Scottish Government (2015) The Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015. Norwich: TSO (The Stationary Office)

- Scottish Government (2016) Health and Social Care Delivery Plan, Edinburgh: The Scottish Government

- Scottish Government/COSLA (2017) National Health and Social Care Workforce Plan part 2: a framework for improving workforce planning across NHS Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Government

- Scottish Health Council (2014) The participation toolkit. Glasgow: Health Improvement Scotland

- Segal S, Silverman CJ and Temkin TL (2011) Outcomes from consumer-operated and community mental health services: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatric Services, 62, 8):915-21.

- Slay J and Stephens L (2013) Co-production in mental health: a literature review. London: New Economics Foundation

- Springham N and Robert G (2015) Experience based co-design reduces formal complaints on an acute mental health ward. BMJ Quality Improvement Reports, 4, 1

- Turner A, Realpe AX, Wallace LM et al (2015) A co-produced self-management programme improves psychosocial outcomes for people living with depression. Mental Health Review Journal, 20, 4, 242-55

- Vackerberg N (2013) The Esther approach to healthcare in Sweden: a business case for radical improvement. Birmingham: Governance International

- Voorberg WH, Bekkers VJJM and Tummers LG (2014) A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Management Review, 2-25

Acknowledgements

This Insight was reviewed by Helen Allbutt (NHS Education for Scotland); Diane Graham, Allan Young and Des McCart (NHS Healthcare Improvement Scotland); Sharon McAleese (Inverclyde Council); Neil MacLeod (Scottish Social Services Council); Steven Marwick (Evaluation Support Scotland); Susan Paxton and Andrew Paterson (Scottish Community Development Centre); Gerry Power (ALLIANCE); Neil Quinn (University of Strathclyde); and Scottish Government colleagues. Comments represent the views of reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of their organisations. Iriss would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time to reflect and comment on this publication.