Introduction

This evidence review was commissioned by Life Changes Trust to explore the evidence around the contribution of community-led approaches to social care and support to human rights and equalities outcomes.

The motivation for this review emerged from an awareness of a lack of understanding of the benefits of, and best practices in, person-centred and community-led social care. A better understanding of these benefits and their relationship to human rights and equalities concerns may serve to inform funding decisions for community-led person-centred interventions and programmes, resulting in increased outcomes for individuals and communities.

Context

Scottish social policy has a strong focus on co-production, emerging from the Commission on the Future Delivery of Public Services (Christie 2011). This approach has been further embedded since Power's (2013) review in the second edition of Co-production of Health and Wellbeing in Scotland. For a comprehensive policy overview of co-production, McGeachie and Power's (2015) report for the Scottish Co-Production Network is recommended.

Approaches that involve working with, rather than doing to, people and communities (referred to using a wide range of terms including person-centred and community-led), are widely reported in Scottish policy as resulting in beneficial outcomes (e.g. McGeachie and Power 2015). The principles of community-led support are co-production, community focus, support and advice to prevent crises, a culture based on trust and empowerment in which people are treated as equals, minimal bureaucracy, and a responsive and proportionate system that delivers positive outcomes (Bown et al. 2017).

These outcomes may be seen to support human rights, which the Health and Social Care Alliance (The ALLIANCE) (2017) outline the national initiatives in Scotland that exist to inform the development and delivery of social services to help realise international human rights in everyday life for everyone in Scotland.

Community-led, or co-produced, approaches to social care and support are one aspect of social policy in Scotland that is informed by rights-based approaches, alongside other initiatives including social security, community empowerment, health and social care integration, the National Performance Framework, the National Clinical Strategy, the Self Management Strategy, the Mental Health Strategy, National Care Standards, person centred care and Self Directed Support (The ALLIANCE 2017). The ALLIANCE suggest the rights-based approach allows policies and practices in social care and support to be delivered on a fair, robust and legal basis whilst making difficult decisions and prioritising budgets.

The culture shift towards collaboration has occurred concurrently with the shift of service delivery from public services to alternative models, for example through social enterprises1. This is encouraged by The Scottish Government (2016), which asserts that social enterprise demonstrates a more inclusive way of delivering social services, by promoting equality and tackling discrimination, supporting gender equality, improving educational attainment and contributing to human rights and democratic participation.

Social enterprises as a means of providing social care and support (Social Enterprise Scotland 2015) are increasing. The Social Enterprise in Scotland Census (2015) produced by Social Value Lab asserts that the voluntary code of practice for social enterprises in Scotland, that outlines the values and behaviours of social enterprises, are aligned to the principles of fairness, equality and opportunity, which it argues are demonstrated through trends in social enterprises' board-level gender balance, executive pay, living wage provision, employment contracts and workplace diversity.

These general outcomes from models of social care and support delivery, including social enterprises and other forms of micro-provision, may be interpreted as making a contribution to human rights and equalities agendas. However, in addition to the more general evidence gap discussed below, there is a lack of evidence explicitly connecting identified outcomes from interventions of this kind to any kind of human rights based framework.

Evidence base

There is a lack of practice-based evidence around community-led person-centred care and support. There is also an overall shortage of evaluation of the outcomes of collaboratively designed interventions and a lack of clarity about how these approaches may be resulting in social development, for example through contributions to equality and human rights. In terms of co-production, Kaehne et al. (2018) argue:

There has been no clear evidence that co-produced services have either led to improved service satisfaction, or that co-produced services resulted in better quality of care for patients or users.

In relation to different overarching approaches, there is a lack of evidence to support the effectiveness or "critical success factors" of personalisation, for example, which makes it extremely difficult to identify the overall impact of the approach (Powell 2012). There is also a lack of research into the impact and outcomes of micro-enterprises in a health and social care context and there has been little formal research into social care and health micro‐enterprise (Lockwood 2013) and very little literature around the implications of these interventions for wellbeing, inequality and social justice (Stickley 2015).

Carr (2014) identifies a similar challenge in finding evidence relating to the impact of non-traditional social care and support providers:

Overall, the research evidence on the effectiveness of local community, specialist or small-scale services is patchy but indicates that information, care and support initiatives are developing in response to actual or perceived difficulties with mainstream provision. There were very few specific service evaluations and none explicitly on small private or not for profit micro-providers or social enterprises.

There is a general lack of evidence of what community solutions are being used and what outcomes these result in (Bown et al. 2017). Where evidence does exist, conclusive arguments for particular approaches and interventions are difficult to make based on the rigour, validity and generalisability of the methods and findings. Although several reports claim that person-centred, community-led services contribute to equality outcomes (for example SCIE 2015), it is not clear where this evidence base is drawn from.

Despite its status within the policy agenda, there is a lack of research directly comparing outcomes in different settings with different models and sources of delivery, for example people's sense of control in different care settings (Callaghan and Towers 2014). With specific regard to co-production, Durose et al. (2015) argue that "co-production has been granted an influential role in the future of public services and indeed public governance on the basis of little formal evidence".

Claes et al. (2010) identify a lack of research on the effectiveness of person-centred planning generally, whether community-led or not, and (Kaehne and Beyer 2014) suggest that a reason for this may be the significant challenges associated with establishing clear evidential links. Due to the often practice-based, policy-led nature of the research phenomenon (person-centred, community-led social support), it would not be appropriate to limit the evidence search to academic content only. However, standards for inclusion have been set based on the need to identify a rigorous, reliable and valid evidence base. For inclusion in this review, therefore, reported interventions require clear empirical (rather than purely theoretical or logical) support, which requires reporting of a reliable implementation of the process and valid assessment of the outcomes (Claes et al. 2010), with outcomes relating to specific equalities and human rights outcomes (discussed below). These standards have been applied to a broad evidence base drawn from academic and grey literature.

Much of the literature identified does not report the application of a robust and explicit theory of change to the reporting, which limits programmes' abilities to identify risks and assumptions that can influence outcomes (Cook 2017) and provides a clear structure of inputs, aims and outcomes that can be used to identify the impact of specific interventions. It was therefore necessary to analyse much of the reporting of impacts making certain assumptions to be able to identify how the projects and programmes may be seen to contribute to equalities and human rights goals.

The impact of collaborative approaches are therefore unclear and would benefit from connection to a more robust evidence base. Furthermore, an exploration of the outcomes of collaboratively developed social care and support may provide a clearer understanding of which specific interventions, developed in which ways, lead to which outcomes and contribute to which national priorities. This can help funders make decisions around resource distribution and enable intermediaries to plan what support may be the most helpful to maximise impact.

Durose et al. (2015) provide two explanations for the "relative weakness" of the evidence base relating to co-production:

First, the breadth of the term and its lack of programmatic focus; and second, the shifting parameters of what constitutes evidence-based policy within government, with an apparent downgrading in the value of qualitative and case study approaches which may be particularly appropriate for evidencing co-production.

It is therefore important to emphasise that an absence of evidence does not necessarily indicate an absence of impact, and instead speaks more to the difficulties associated with evidencing outcomes from social care projects when they relate to 'soft' measures and overarching strategic goals such as human rights, where it is difficult to identify, measure, isolate and attribute the effects of specific interventions.

Background

Third sector and independent provision of social care

The involvement of charities, community organisations and the third sector in health and social care provision and identification of equalities and human rights outcomes has a complex history across the UK. For example in England, the Marmot Review (Institute of Health Equity 2010) into health inequalities promoted charity, community organisation and third sector involvement in provision as being more appropriately situated than the public sector to challenge inequality for marginalised populations (Marmot 2010 in Stickley 2015).

The introduction of the SDS Scotland Act in 2014 has been seen by some social services providers as an opportunity to radically change social care provision (Community Catalysts 2015). A central focus of the Act is personal outcomes, co-production and individual choice in care and support, which, it is frequently suggested, lead to positive outcomes, including relating to equalities and human rights, such as personhood and maximising autonomy (Crandall et al. 2007) access to support (World Health Organisation 2018) and shared decision making in care planning (World Health Organisation 2015).

However, claims or intentions around person-centredness and community-led/basedness do not automatically lead to positive outcomes, and where these outcomes are achieved it is important to evidence them robustly. This review therefore explores the available evidence on person-centred social care and support where it takes an explicitly community-led approach. Although more general ideological pieces about the human rights outcomes of person-centred community-led approaches to social care have been produced, this is not the focus of this review, which sought to identify the specific outcomes of individual interventions.

Theoretical framework

Much of the evidence around positive impacts and outcomes of community-led and/or person-centred approaches to social care and support do not take an explicit approach to connecting outcomes to indicators of equalities and/or human rights. It was therefore necessary to apply a theoretical framework to the analysis of the evidence. This is viewed through a human rights lens. Human rights are based on the principle of respect for the individual and they are the rights and freedoms that belong to every person, at every age. They are set out in international human rights treaties and are enshrined in UK law by the Human Rights Act 1998 (Scottish Government 2017a).

The Scottish Human Rights Commission (2016) emphasises the value of considering human rights in approaches to services:

A human rights based approach empowers people to know and claim their rights. It increases the ability of organisations, public bodies and businesses to fulfil their human rights obligations. It also creates solid accountability so people can seek remedies when their rights are violated.

Informed by this principle, the theoretical framework for this review draws on two key resources: the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) Measurement Framework (2017) and the Scottish Government National Performance Framework (2016). It uses the themes within these documents as a method for analysing the evidence that was identified and shortlisted using the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Appendix A). These themes are discussed below.

EHRC Measurement Framework

The Equality and Human Rights Commission's (2017) comprehensive framework has several strengths:

First, it has strong theoretical foundations (equality, inequality, capability, human rights, vulnerability and intersectionality) that are applied to equality and human rights monitoring in a practical way. These theoretical foundations connect closely to the Scottish Government's approach to social care and support, for example strengths-based approaches (Pattoni 2012).

Second, it translates the central and valuable freedoms and opportunities into outcomes and provides precise indicators and topics.

Third, it provides detailed guidance on what structure, process and outcome evidence to look at, with a single framework that can be applied across England, Scotland and Wales. This is useful in an evidence review of outputs from across the UK.

Finally, the resource is designed to allow third-sector organisations, NGOs and charities to use the framework as an agenda-setting tool. This supports the evidence review's utility in the specific context in which it was commissioned.

This review draws on different aspects of the six domains within the Framework (education, work, living standards, health, justice and personal security and participation). Within these domains are a wide variety of indicators and topics to identify how human rights and equalities goals can be measured. After shortlisting the search results to identify those that report on individual or syntheses of interventions and their outcomes, the articles and other outputs were analysed using the Frameworks to pull out where the reported impacts may connect to human rights and equalities indicators. The capabilities, outcomes, indicators and topics within these domains are available in the ECHR (2017) framework and due to their length and complexity are not reproduced within this review.

National Performance Framework (NPF)

The purpose of the National Performance Framework (NPF) is to provide a clear vision for Scotland with broad measures of national wellbeing covering a range of economic, health, social and environmental indicators and targets. In its Programme for Scotland 2016-17, the Scottish Government committed to integrate human rights within the NPF, "to help locate human rights at the centre of policy-making and delivery for the Government and the public sector." (The ALLIANCE 2017)

The Scottish Government National Performance Framework (2016) has considerable overlap with the EHCR Framework, but also includes specific indicators for Scotland, such as those relating to business development. The framework exists "to focus government and public services on creating a more successful country, with opportunities for all of Scotland to flourish, through increasing sustainable economic growth".

This review draws on the following indicators:

- Increase the number of businesses

- Improve the skill profile of the population

- Reduce underemployment

- Reduce the proportion of employees earning less than the Living Wage

- Reduce the pay gap

- Increase the proportion of young people in learning, training or work

- Improve children's services

- Improve support for people with care needs

- Reduce emergency admissions to hospital

- Improve the responsiveness of public services

- Improve people's perceptions of their neighbourhood

- Increase people's use of Scotland's outdoors

General reporting of how collaborative approaches enable participation from individuals and communities is not considered a sufficient evidence base and for inclusion in this review. Reporting needed to explicitly identify specific outcomes of specific person-centred, community-led social care and support interventions. This also means that the outcomes, rather than the stated inputs identified, must demonstrate a contribution to equality and human rights. These are not necessarily explicitly stated as being human rights or equalities outcomes, but relate to the outcome indicators identified by the Equality and Human Rights Commission's (2017) Measurement Framework.

PANEL principles

The PANEL principles are one way of breaking down what a human rights based approach means in practice to inform the design, delivery and assessment of care and support. PANEL stands for Participation, Accountability, Non-Discrimination and Equality, Empowerment and Legality:

| Participation | People should be involved in decisions that affect their rights. |

| Accountability | There should be monitoring of how people's rights are being affected, as well as remedies when things go wrong. |

| Non-Discrimination and Equality | All forms of discrimination must be prohibited, prevented and eliminated. People who face the biggest barriers to realising their rights should be prioritised. |

| Empowerment | Everyone should understand their rights, and be fully supported to take part in developing policy and practices which affect their lives. |

| Legality | Approaches should be grounded in the legal rights that are set out in domestic and international laws. |

In analysing reports and case studies of interventions, this review considers whether the PANEL principles are demonstrated in the reporting of outcomes. Publications that report on design and delivery without the specific identification of outcomes are not included.

It should be emphasised that this is not a comprehensive theoretical framework. A robust model to be developed would involve significant research and planning as part of a larger scale research project.

Methods

There are a wide range of reported outcomes in the literature within a broad range of categories, including cost benefit, social capital and social value. It was not within the scope of the review to identify all reported impacts of community-led, person-centred approaches to social care and support; this review focuses on human rights-based outcomes using specific indicators within a theoretical framework.

Although a systematic approach was taken to searching the evidence base, this review should not be considered to be a comprehensive systematic review.

Search

A structured and systematic approach was taken to literature searching. Sources searched include academic databases (ProQuest: ASSIA, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, Public Health Database), Google Scholar, hand searching key journals and citation mining.

Search limits included international research from 2010 (literature reviews may include earlier studies and research), with results limited by language (English) and publication type (scholarly journals and grey literature).

As discussed, collaborative approaches to service design and delivery are central to the Scottish Government's agenda for social care and support. Within the policy and practice landscapes, terminology for collaborative principles is varied and often used interchangeably. For example, the term 'co-production' is often used interchangeably with 'co-delivery' and 'co-design' although 'co-delivery' (actual delivery of services by a number of stakeholders) is different to 'co-design' (a number of stakeholder groups informing and designing services) (Scottish Government 2017b). This review incorporates the broad spectrum of collaborative approaches and identifies the key terms used for searching and analysis within the methodology. For example, search terms included co-creation, co-design, co-planning, co-management and co-assessment.

Search terms and strings were developed based on the search focus, and included terms relating to: self directed support; person-centred; people-led; community-led; community-based; user-centred design; micro-provision; micro-enterprise; social enterprise; community organisation; co-operative; and voluntary organisation. Outcomes and impacts searched for included: human rights; equality; equity; social justice; employment; occupation; access; inclusion; participation; cohesion; dignity; disability; gender; race; ethnicity; reintegration; rehabilitation and resettlement.

A thorough search of the grey literature was also conducted, both through general searching, the use of specialist databases (Social Care Online) and combing through key websites, including Iriss, Evaluation Support Scotland, Scottish Government, Nesta, What Works Scotland, Scottish Co-Production Network, and the Joint Improvement Team.

Shortlisting

A set of inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the search results to meet the requirements for the focus of the review (Appendix A). The strict inclusion criteria and application of critical appraisal principles, including TAPUPAS (Pawson et al. 2003) and other key questions for evaluation (Orme and Shemmings 2010) resulted in a significant amount of search results being rejected as a result of not sufficiently meeting the characteristics set out.

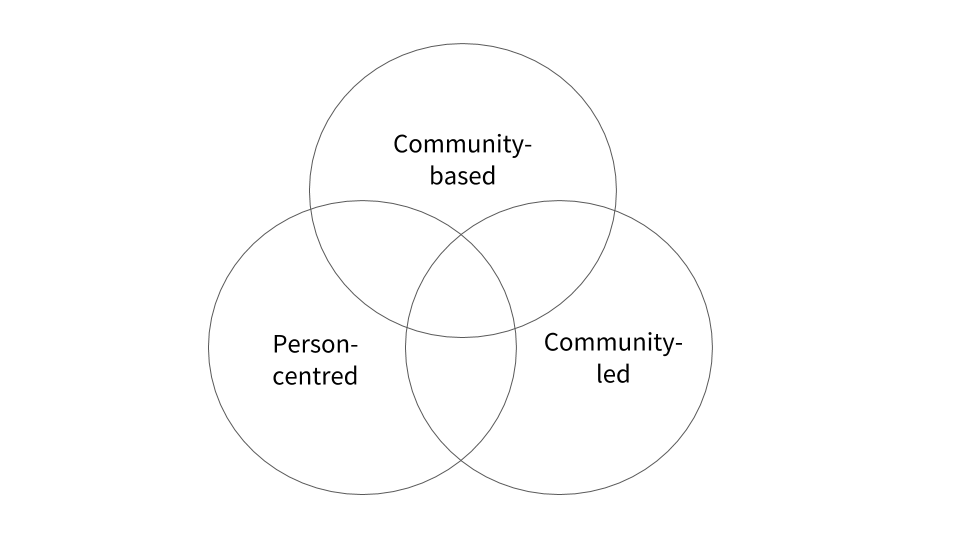

The focus of this review is on social support and care interventions that take place in the community, with a person-centred and/or community-led approach.

For the purposes of this review we define these as:

Social support and care: Interventions around support and help that are designed to improve quality of life and enable people to live in their own homes.

Community-based: Activities that take place within the community rather than locations typically (although not necessarily accurately) considered to not be part of the community, such as hospitals and care homes.

Community-led: Activities that are designed and run by people within the community, rather than social services providers or people working within private or voluntary sector organisations who are not part of the community.

Person-centred: Interventions that focus on the elements of care, support and treatment that matter most to the patient, their family and carers.

Analysis

Very few interventions present themselves as community-based, person-centred and community-led, and even fewer explicitly so. It was therefore necessary in some cases to infer these approaches from the reporting of the projects. This was achieved through a method referred to as process coding (Corbin and Strauss 2015), in which semantic clues within qualitative data are identified to infer how activities/processes can result in particular outcomes (Macauley et al. 2017). This provided the ability to identify how outcomes relate to human rights, regardless of whether this was an intended impact. However, it is therefore possible that these approaches have been attributed to some projects in error. This is another reason to consider the findings of this review indicative only.

Human rights indicators are complex and broad and do not appear to be a typical way of mapping the outcomes of social services interventions. To do this thoroughly would require human rights to be applied as a framework at the conception of interventions and throughout the evaluation process. The application of a theoretical framework after the fact can only be seen as indicative.

General limitations

The nature of person-centred, community-led approaches to social care and support means that formal evaluation tools may not fit this informal, local context and it is important to take a broad approach to inclusion of evidence in this review. Even so, there are some basic standards of evaluation and evidence generation that the evidence identified does not meet. Several of the studies identified:

- Relied on case studies

- Aimed for specific purposes that do not relate to HR outcomes

- Lacked independent evaluation

- Had a pre-existing commitment to specific approaches/models

- Lacked longitudinal evaluation - snapshots of success

Findings: human rights and equalities outcomes

This review presents the evidence relating to equalities and human rights outcomes of person-centred, community-led social care provision from a set of examples from academic and grey literature. It is not exhaustive, and does not focus on several kinds of outcomes or benefits identified in the outputs, such as satisfaction, and self-reporting of happiness and wellbeing.

Summary of shortlisted reports

Beech, R et al. (2017) Delivering person-centred holistic care for older people. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 18(2), pp.157-167 (paywalled)

This paper is an evaluated case study of the Wellbeing Coordinator (WBC) service in Cheshire, UK. WBCs are non-clinical members of the GP surgery or hospital team who offer advice and support to help older people with long-term conditions and unmet social needs remain independent at home.

A mixed method design assessed the outcomes of care for recipients and carers using interviews, diaries and validated wellbeing measures. Service utilization data, interviews and observations of WBC consultations enabled investigation of changes in processes of care. Data were analysed using simple descriptive statistics, established instrument scoring systems and accepted social science conventions.

Bown, H et al. (2017) What works in community led support? Findings and lessons from local approaches and solutions for transforming adult social care (and health) services in England, Wales and Scotland (pdf)

This summary draws together the headline findings and lessons from an evaluation of the Community Led Support (CLS) Programme hosted by the National Development Team for Inclusion (NDTi). The NDTi supported seven local authorities and their partners to plan, design, implement and evaluate a new model of delivering community based care and support. The findings report on outcomes of the projects collectively. Some outcomes connect to specific impact indicators that relate to human rights and equalities outcomes and are presented in the table below. Other descriptors of impact are identified by the authors but these cannot be defined as indicators of impact and may be viewed as descriptors of outputs.

A limitation of the report is that there appears to be some conflation of outputs and outcomes and more work may be required to distinguish between the two to rigorously evaluate impact. There is also a lack of robust data on community solutions, which the CLS Programme reports it is working on. Significant challenges around the consistent recording, sharing and tracking of data on system efficiencies and use of resources are reported. The authors speculate that this may be due to limited analytical capacity, numbers of skilled people, and the technological infrastructure to handle new data sources alongside current reporting requirements.

Bull, M and Ashton, A (2011) Baseline survey: mapping micro-providers in the personalisation of health and social care services. Manchester Metropolitan University (pdf)

This baseline study identified that the majority of micro-providers offer specialist support and were established to help people and communities in a local area. The objectives of the research were to build primary research evidence of micro-providers, highlighting; size, scope, services, type of business, development, motivations, income, hours of work, client base, staffing, benefit and added value they provide to end users and the local authorities and wider public sectors and the communities in which they work.

The researchers conducted 23 face-to-face and telephone interviews with micro-providers. For several reasons, including sample size, accuracy of business type and geographical proximity, the findings cannot be considered generalisable.

Devine, L and Parker, S (2015) The SAFER initiative: a case study in applying research to social enterprise: creating impact. Ideas for Good, Bristol, UK, 21 April 2015 (pdf)

The SAFER Initiative is a social enterprise venture, providing support around the child protection and safeguarding referral and assessment process. The Initiative focuses on professionals covered by s.11 Children Act 2004 who have a duty to refer families for social work assessment where there are child protection or safeguarding concerns, and support for the families who are referred and assessed. The Initiative is piloting bespoke training for professionals who may need to refer families for social work assessment, coupled with pro bono advice and support for families undergoing referral and assessment.

This report was shortlisted because it reported on the work of a social enterprise, but the paper does not report on actual outcomes of the work and therefore cannot be included in the final review. A follow-up report of outcomes was searched for but not identified.

Fieldhouse, J et al. (2011) Evaluation of an occupational therapy intervention service within homeless services in Bristol. University of the West of England (pdf)

This report presents the findings of an evaluation of an occupational therapy intervention service as part of homeless services in Bristol. Two full-time, temporary posts were established at the Redwood House hostel and supported by supervisors based at the University of the West of England. The intervention reports to have taken a person-centred approach and aimed to increase the percentage of vulnerable people progressing towards independent living from emergency accommodation, and to improve service user involvement within hostels. Specific interventions included breakfast groups, library and internet sessions, tenancy skills groups, job/voluntary work hunting, individual and group cooking, running/jogging, gardening, park activities, shopping and goal-setting.

The evaluation does not describe a specific methodology and does not measure actual outcomes of activities, but includes some examples of outcomes as reported by the occupational therapists and feedback from people involved in the intervention as part of the description of the stages of the work undertaken.

Godfrey, F (2013) Reshaping care for older people community capacity building / coproduction case study. Community Connections / Joint Improvement Team (pdf)

This case study presents the activities of an intervention in Falkirk, which supports those in the early stages of dementia and their carers. Although no methodology is provided the report includes outcomes of the Community Connections project identified by Alzheimers Scotland.

Heritage, G (2014) Reshaping care for older people community capacity building / coproduction case study. Argyll and Bute –Timebanking (pdf)

This case study reports the outcomes of a timebanking activity that takes place across six different localities in Argyll and Bute. Volunteers contribute time to a wide range of tasks, experience and support including skills sessions, practical support, emotional support, and advocacy. Specific anticipated outcomes of the interventions are identified. As these outcomes are not actual and have not been measured these cannot be included in the indicators section of this report. However, anticipated outcomes include:

- Reduction in emergency admissions and readmissions

- Older people live more active lives fully engaged in their communities

- More older people are able to live in their home for longer

- Prescribing levels are reduced

- Community capacity is built and older people are better engaged and active in their communities

Owen, F et al. (2015) Social return on investment of an innovative employment option for persons with developmental disabilities: Common Ground Co-Operative. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 26(2), pp.209-228 (paywalled)

The authors examine the monetary value of a grassroots initiative that became a co-operative in Ontario, Canada, formed to provide educational, administrative, and job coach support to adults with developmental disabilities. The co-operative offers job skills training, work experience, job coaching, opportunities for enterprise partnerships, financial support, and health benefits.

The core values of the co-operative are "co-operation, empowerment, entrepreneurship, inclusion, independence, initiative, integrity, respect and teamwork". The authors conducted interviews and focus groups to identify the outcomes of the activities of the co-operative's work. Using inductive and deductive coding based on factor headings from Schalock and Verdugo's (2012) quality of life personal outcomes, the impacts of the project are identified.

Scottish Care (2017) A human rights based approach to self directed support for older people: an analysis of the Scottish Care Getting it Right for/with Older People Project, January 2016-June 2017 (pdf)

The Scottish Care (2017) report 'A human rights based approach to self-directed support for older people: an analysis of the Scottish Care Getting it Right for/with Older People Project, January 2016-June 2017' reports that it presents a framework for how the Getting it Right for/with Older People project utilised the PANEL approach to identify and evidence how human rights were embedded in practice when achieving each of the short- and long-term project outcomes, connecting these outcomes to the principles of self-directed support.

This report was shortlisted because it included case studies, but these case studies report on the application of an approach to intervention not the evaluation of outcomes from an intervention.

Windle, K et al. (2009) The national evaluation of partnerships for older people projects: executive summary. Personal Social Services Research Unit (pdf)

The Partnership for Older People Projects (POPP) were funded by the Department of Health to develop services for older people, aimed at promoting their health, well-being and independence and preventing or delaying their need for higher intensity or institutional care. The evaluation found that a wide range of projects resulted in improved quality of life for participants and considerable savings, as well as better local working relationships.

The full report of this work is almost 300 pages long so it was not feasible within the scope of this review to analyse the full document. The executive summary was therefore used as a topline identification of key themes.

Indicators of key human rights and equalities outcomes

The outcomes reported in the shortlisted papers above address several of the key human rights and equalities indicators discussed in the reference documents used in the development of the theoretical framework of this review. They are discussed below.

Education

To be knowledgeable, to understand and reason, and have the skills and opportunity to participate in parenting, the labour market and in society (ECHR 2017)

Bull and Ashton (2011) reported the majority of participants increased their skills, although it is not clear where or how the organisations they spoke to recorded this data.

Owen et al. (2015) also reported that participants felt they had developed skills and abilities to support their independence.

Work

To work in just and favourable conditions, to have the value of your work recognised, even if unpaid, to not be prevented from working and be free from slavery, forced labour and other forms of exploitation (ECHR 2017)

Owen et al. (2015) report that an outcome of the Common Ground Co-Operative was that people working there felt that their work was recognised. Although the pay was not high, participants reported feeling pride associated with earning an income.

Bull and Ashton (2011) reported that several micro-organisations in their study had paid employees. 50% of micro-providers in the study reported they pay staff between £15-16,000, with 25% paying £13-14,500 and 25% paying greater than £19,500.

Living standards

To enjoy an adequate standard of living, with independence and security, and be cared for and supported when necessary (ECHR 2017)

Godfrey (2013) reports that the Community Connections project supports people to maintain independence at home for as long as possible following dementia diagnosis. Another outcome was that participants had access to a support network.

Health

To be healthy, physically and mentally, being free in matters of sexual relationships and reproduction, having autonomy over care and treatment, and being cared for in the final stages of your life (ECHR 2017)

Several papers included in the analysis identified health outcomes that can be mapped to human rights indicators.

Owen et al. (2015) report that the impacts of the Common Ground Co-Operative are:

- Independence: increased independence, general work skills, skills specific to the enterprise

- Social participation: feeling supported, developing new friendships, initiating social activities

- Wellbeing:

- Emotional: pride in accomplishment, empowerment, self confidence, motivation, happiness, self-expression

- Health: weight loss, increased activity

- Material: pride in earning income, spending money

In reporting the activities undertaken by occupational therapists within homeless services, Fieldhouse et al. (2011) report wellbeing outcomes that occurred as a result of engaging in cooking activities.

Godfrey (2013) reports that a key outcome of the Community Connections programme is that people with dementia participate in physical activities which helps them to remain as healthy as possible.

Beech et al. (2017) report that outcomes of the Wellbeing Coordinator (WBC) service include improvements in the wellbeing of people with long-term conditions, including people feeling more confident and in control of their lives.

Participation

To participate in decision making and in communities, to access services, to know that your privacy will be respected, and to be able to express yourself (ECHR 2017)

Godfrey et al. (2013) identified that an outcome of the Community Connections project was that people could maintain community links.

Beech et al. (2017) report that outcomes of the Wellbeing Coordinator (WBC) service include access to social networks, maintenance of social identity and valued activities.

Conclusion

First, it is important to reiterate that the findings of this review should be considered indicative, and not comprehensive. A much larger review with a robust methodology, analytical framework and scale would be needed to comprehensively determine whether existing evidence of the outcomes of person-centred, community-led interventions in social care have an impact on human rights and equalities. An appropriate avenue for this would be a university or research institute.

Much of the grey literature from governments, commissioning bodies and funders expresses positive perceptions of person-centred, community-led interventions for social care provision within the self-directed support context, but more evidence is needed to rigorously demonstrate how these interventions and the approaches they take lead to specific outcomes around social justice, human rights, equality and prevention. Specifically, more measurement of the impact of interventions is needed to generate adequate data to identify impact of the approach, including in comparison to other approaches.

It was not within the scope of this review to provide a history of the evolution of social enterprises and private bodies within health and social care provision, but it is necessary to highlight the apparent ideological rather than evidence-based foundation for health and social care policies (Stickley 2015). Further exploration of these issues should include consideration of the ethical tensions around the discourses, practices and models of social services, for example the ways in which social entrepreneurship works to "confer responsibility from the state to individuals and communities within civil society" but also how this occurs not only through control, but also through the provision of freedoms not previously conferred on social care providers (Dey and Steyaert 2016) and the ways this can create the conditions to achieve equalities and human rights outcomes.

There may be a need to develop consistent approaches to impact evaluation to compare intervention effects across the large number of small-scale programmes extant within the self-directed support landscape. This may be achieved in collaboration with academic partners, as exemplified by The Department of Allied Health Professions at the University of the West of England, Bristol.

Further research is needed to explore the comparative impact of different approaches to supporting micro-enterprises, in addition to research into the comparative impact of micro-enterprises and alternative models of service delivery.

Next steps

Further research may wish to compare outcomes of different models of social care and support delivery to identify which approaches lead to the most successful impacts. There is currently a lack of empirical evidence to demonstrate that the reported advantages (and disadvantages) are sustainable, or uniquely connected to specific delivery models and that the benefits could not be replicated or improved within alternative formats. This requires the collection and use of more consistently recorded and better local data on the delivery and implementation of community-led services, and individual outcomes, that can be shared and aggregated at the national level to identify trends and transferable lessons (Bown et al. 2017). A more robust data set may also minimise the evaluation burden at the local level (Ibid). However, it is important to acknowledge that data sets do not provide the full picture at a local level, and that qualitative approaches such as appreciative inquiry and peer to peer learning may complement data sharing to strengthen the evidence base for collaborative approaches to social care and support (Durose et al. 2015).

A useful resource for evaluating human rights based interventions has been produced by Donald (2012). This guide provides a starting point for health and social care organisations that wish to evaluate the impact of human rights-based interventions. It does not suggest a single or 'right' way of approaching evaluation. It examines a wide variety of methods that have been used in previous evaluations of human rights-based projects and may be relevant to projects that anticipate human rights-based outcomes despite not being explicitly or solely human rights-focused.

References

- The ALLIANCE (2017) Being human: A human rights based approach to health and social care in Scotland (pdf)

- Beech, R et al. (2017) Delivering person-centred holistic care for older people. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 18(2), pp.157-167 (paywalled)

- Bown, H et al. (2017) What works in community led support? Findings and lessons from local approaches and solutions for transforming adult social care (and health) services in England, Wales and Scotland (pdf)

- Bull, M and Ashton, A (2011) Baseline survey: mapping micro-providers in the personalisation of health and social care services. Manchester Metropolitan University (pdf)

- Callaghan, L and Towers, A-M (2014) Feeling in control: comparing older people's experiences in different care settings. Ageing & Society, 34(1), pp.1427-1451 (author repository copy)

- Carnegie UK Trust (2018) Roundtable report: co-produced evidence and robust methodologies (pdf)

- Carr, S (2014) Social care for marginalised communities: balancing self organisation, micro-provision and mainstream support. Policy paper 18. University of Birmingham (pdf)

- Christie, C (2011) Commission on the future delivery of public services. Scottish Government (pdf)

- Claes, C et al. (2010) Person-Centered Planning: Analysis of Research and Effectiveness. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 48(6), pp.432-453 (paywalled)

- Community Catalysts (2015) Self-Directed Support (SDS) in Scotland and Community Catalysts' work in Dumfries and Galloway (website)

- Cook, A (2017) Outcomes based approaches in public service reform. What Works Scotland position paper February 2017 (pdf)

- Corbin J and Strauss A (2015) Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th edition. CA: Thousand Oaks.

- Crandall, L et al. (2007) Initiating person-centered care practices in long-term care facilities. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 33(11), pp.47-56 (paywalled)

- The Department of Allied Health Professions (2018) Service evaluations (website)

- Devine, L and Parker, S (2015) The SAFER initiative: a case study in applying research to social enterprise: creating impact. Ideas for Good, Bristol, UK, 21 April 2015 (pdf)

- Dey, P and Steyaert, C (2016) Rethinking the space of ethics in social entrepreneurship: power, subjectivity, and practices of freedom. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(4), pp.627-641 (Open Access)

- Donald, A (2012) A guide to evaluating human rights-based interventions in health and social care. Human Rights & Social Justice Research Institute, London Metropolitan University (pdf)

- Durose, C et al. (2017) Co-production: joint working between people or groups who have traditionally been separated into categories of user and producer. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 13(1), pp.135-151 (author repository copy or paywalled)

- Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) (2017) Measurement framework for equality and human rights (pdf)

- Fieldhouse, J et al. (2011) Evaluation of an occupational therapy intervention service within homeless services in Bristol. University of the West of England (pdf)

- Godfrey, F (2013) Reshaping care for older people community capacity building / co-production case study. Community Connections / Joint Improvement Team (pdf)

- Heritage, G (2014) Reshaping care for older people community capacity building / coproduction case study. Argyll and Bute –Timebanking (pdf)

- Kaehne, A (2018) Co-production in integrated health and social care programmes: a pragmatic model. Journal of Integrated Care, 26(1), pp.87-96 (paywalled)

- Kaehne, A and Beyer, S (2014) Person-centred reviews as a mechanism for planning the post‐school transition of young people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58)(7), pp.603-613 (paywalled)

- Lockwood, S (2013) Micro enterprise: community assets helping to delivery health and wellbeing. Journal of Integrated Care, 21(1), pp.26–33 (paywalled)

- Macauley, B et al. (2017) Conceptualizing the health and well-being impacts of social enterprise: a UK-based study. Health Promotion International, epub ahead of print (Open Access)

- Institute of Health Equity (2010) Fair Society Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review) (website)

- McGeachie, M and Power, G (2015) Co-production in Scotland: a policy overview (website)

- National Development Team for Inclusion (2017) Community led support: sharing the learning from Scotland (pdf)

- National Development Team for Inclusion (NDTi) (2017) Community led support (website)

- Orme, J and Shemmings, D (2010) Developing research based social work practice. London: Macmillan International Higher Education (book)

- Owen, F et al. (2015) Social return on investment of an innovative employment option for persons with developmental disabilities: Common Ground Co-Operative. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 26(2), pp.209-228 (paywalled)

- Pattoni, L (2012) Strengths-based approaches for working with individuals. Iriss Insight 16 (pdf)

- Pawson, R et al. (2003) Types and quality of social care knowledge stage two: towards the quality assessment of social care knowledge. ESRC UK Centre for Evidence Based Policy and Practice: Working Paper 18 (pdf)

- Powell, JL (2012) Personalization and community care: a case study of the British system. Ageing International, 37(1), pp.16-24 (paywalled)

- Social Care Institute for Excellence (2015) Community-led care and support: a new paradigm (pdf)

- Scottish Care (2017) A human rights based approach to self directed support for older people: an analysis of the Scottish Care Getting it Right for/with Older People Project, January 2016-June 2017 (pdf)

- Scottish Government (2017a) Health and social care standards: my support, my life (pdf)

- Scottish Government (2017b) Review of the community-led regeneration approach as delivered via the People and Communities Fund (website)

- Scottish Government (2016) A fairer Scotland for disabled people (pdf)

- Scottish Government (2016) National performance framework (pdf)

- Scottish Human Rights Commission (2016) A human rights based approach: an introduction (pdf)

- Scottish Human Rights Commission (no date) Scotland's national action plan for human rights (SNAP) (website)

- Stickley, A (2015) An exploration of occupational therapy practice in social enterprises in the UK. Doctoral thesis. The University of Northampton (Open Access)

- Social Enterprise Scotland (2015) First ever census reveals major impact of Scotland's social enterprises (website)

- Social Value Lab (2012) Voluntary code of practice for social enterprises in Scotland (pdf)

- Windle, K et al. (2009) The national evaluation of partnerships for older people projects: executive summary. Personal Social Services Research Unit (pdf)

- World Health Organisation (2018) What are integrated people-centred health services? (website)

- World Health Organisation (2015) People-centred and integrated health services: an overview of the evidence (pdf)

Appendix A: Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

| Include | Exclude | |

| Format | Journal article

Policy document Conference paper Presentation slides |

Non-textual outputs (audio, video) |

| Study type | Systematic review

Literature review Scoping review Primary research Secondary research Case study |

Opinion piece

Book review |

| Outcomes | Human rights or equality indicators | No human rights or equality outcomes identified |

| Year | 2010 onward | Before 2010 |

| Language | English | Not in English |

| Subject area | Health

Social care Management and leadership Public policy Community development Psychiatry Occupational therapy |

Not in the inclusion categories |

| Population | Any | Any |

| Location | International with comparable social welfare structure | Not comparable with Scottish social welfare structure |

| Setting | Residential care

Care home Community based |

Hospital

Acute |

| Intervention type | Social care

Disability (physical, cognitive, psychological) |

Clinical

Dentistry |

| Intervention approach | Co-design

Participatory design Co-production Person-centred Community-led |

None of the included approaches identified |

Notes

-

A social enterprise is a business with primarily social objectives whose surpluses are principally reinvested for that purpose in the business or in the community, rather than being driven by the need to maximise profit for shareholders or owners (Welsh Assembly Government 2010). ↩