Introduction

This evidence summary seeks to address the following questions relating to assessment processes for children across health and social care:

- What are children's and families' experiences of the assessment process in social services?

- What works to make it more accessible and pleasant for them?

About the evidence presented below

In producing this Outline, we searched for evidence relating to good practice and childrens' and families' experiences of common assessment frameworks, early intervention, integrated assessment and integrated children's systems, in the fields of child protection, social work, social care, family law, criminal justice and other relevant fields. We searched for research and evidence reporting on partnership working, integrated approaches, relational work, asset-, capabilities- and strengths-based approaches. We also considered evidence relating to the assessment process as well as aspects of child protection such as family group conferences where the topic of research may also be informative and applicable to principles of practice in assessment.

Although there is some strong evidence of general good practice approaches to assessment, there is a lack of knowledge around what works in assessment in child protection specifically. Godar et al. (2017) conducted a literature review for Research in Practice on current systems and practice in child protection. It is part of a wider project which seeks to identify:

- The evidence base for effective systems, interventions and practice in child protection and work with vulnerable children

- How local authorities engage with and use that evidence in designing local systems, commissioning interventions and supporting social work practice

- Information about costs and benefits of specific interventions as they are implemented in practice

- An overview of demand for child protection services and the extent to which this demand is being met in local authorities across England.

In the literature review stage of this project they seek to answer the question: "where and how are local authorities doing things presented as good practice in published reports in relation to improving child protection systems and practice?"

The authors identified significant gaps in the evidence:

- Most of the reports and research identified provided information about the context in which local authorities are operating, rather than how individual local authorities are responding to that context

- There is no national overview of which approaches to practice, interventions or organisational arrangements are being in used in different places

- The evidence for activity in individual authorities is partial and fragmented, with available publications providing examples from a small sample of authorities and only on specific themes, or areas of activity. Much local authority activity is hidden from view. It is therefore impossible to provide a comprehensive and accurate overview of which local authorities are delivering activities presented as good practice in published reports

They also identified a lack of evidence around the efficacy of assessment frameworks:

In order to continuously improve assessment practice, local authorities have introduced assessment frameworks and tools. However, there are very few assessment tools that have been validated as effective for assessing needs of vulnerable children and families in the UK. Some local authorities are developing their own assessment tools based on their interpretation of research and practice wisdom.

In conducting the search for the present review, we encountered very similar challenges to identifying relevant evidence to Godar et al. (2017), who clearly outline the limitations of the current evidence base in this area:

The evidence available regarding 'how and where authorities are undertaking such activity' is essentially a series of case studies, enhanced by a few small-scale comparative studies providing some insight into how consistently each approach is being implemented. The evidence is skewed towards innovation, rather than embedded good practice, and towards government-funded projects over local initiatives – likely reflecting the challenges associated with local evaluation activity. There is little data on how local authorities are implementing various changes, the barriers to improvement or the influence of inspection or statutory guidance on attempts to innovate.

In terms of the activity that is documented, we know little about the motivations, attitudes, and knowledge that guide local authority decision-makers to select particular interventions or undergo particular reforms. We do not know what information they draw on to make these decisions, either about their local context or about what other authorities are doing. This may be a barrier in local authorities learning from each other as it is not always clear what problem the originating authority was trying to solve, or the values and vision that guided the development of that particular approach.

Nevertheless, this evidence review provides links to relevant resources for those working on the development of integrated assessments. It includes summaries and abstracts of research and practice outputs focusing on overviews of integrated assessments and evidence relating to child and family experiences of assessment. It provides examples of good practice recommendations with regard to the use of frameworks and the assessment more generally, interagency working, involving children and families, and considerations around the ethical and appropriate use of electronic information systems and attendant issues of data security and privacy.

Accessing resources

We have provided links to the materials referenced in the summary. Some materials are paywalled, which means they are published in academic journals and are only available with a subscription. Some of these are available through the The Knowledge Network with an NHS Scotland OpenAthens username. The Knowledge Network offers accounts to everyone who helps provide health and social care in Scotland in conjunction with the NHS and Scottish Local Authorities, including many in the third and independent sectors. You can register here. Where resources are identified as 'available through document delivery', these have been provided to the original enquirer and may be requested through NHS Scotland's fetch item service (subject to eligibility).

Where possible we identify where evidence is published open access, which means the author has chosen to publish their work in a way that makes it freely available to the public. Some are identified as author repository copies, manuscripts, or other copies, which means the author has made a version of the otherwise paywalled publication available to the public. Other referenced sources are pdfs and websites that are available publicly.

Background

In Scotland there is a range of local and national strategies, policies and priorities for children, young people and their families, which contribute to the Scottish Government's aim of taking a unified approach to children's services (Scottish Government 2005). Examples include:

- Single outcome agreement (SOA) priorities

- National Policies: Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC); Early Years Framework (EYF); Curriculum for Excellence

- Local authority policies: e.g. corporate parenting strategy; autism strategy

- NHS policies: annual plans and local delivery plans

- Legislation: Children and Young Persons Act (Scotland) 2014

These strategic drivers feed into Integrated Children's Services Plans, which as part of Scottish Government strategy may include integrated approaches to assessment:

We propose to develop, with agencies, a single integrated assessment, planning and recording tool for use within a framework of co-ordinated meetings, reviews and planning. These arrangements will in time replace meetings about child protection, looked after children, joint assessment, youth offending and other inter-agency arrangements…We propose that where a child's needs are complex, serious, require multi-agency input or are likely to require compulsory measures, an action plan must be agreed by all agencies involved and kept under review. The action plan will be the principal source of information for the Reporter if the child is subsequently referred. (Scottish Government 2005)

Getting It Right For Every Child (GIRFEC)

One significant strategic driver is GIRFEC - a national programme that aims to improve the wellbeing of all children and young people by improving assessment, decision-making, planning and multi-agency working. The early recognition of need, appropriate referral to, and information sharing with, partner organisations leading to streamlined assessment, decision-making, planning and joint working are core components of GIRFEC. (Clackmannanshire Council and Stirling Council 2015)

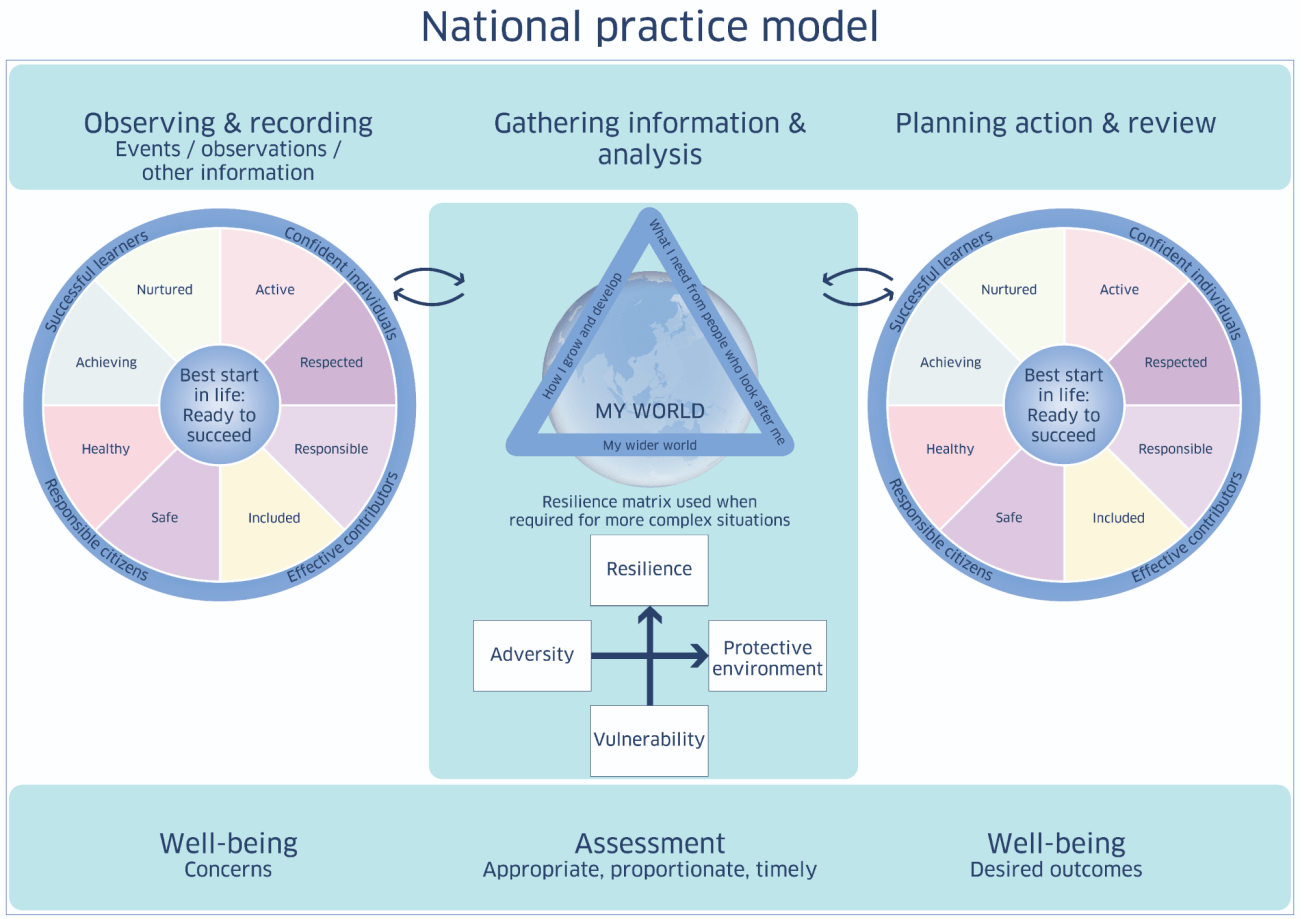

As Coles et al. (2016) summarise, GIRFEC framework consists of 2 key elements:

- The roles of Named Person and Lead Professional

- The National Practice model (comprising 3 assessment tools and a single child's plan, used by practitioners for assessment, planning, and action).

These elements are underpinned by GIRFEC's core components and supported by the legislation that puts the concept of well-being and the role of the Named Person into statute. The core components are:

- A focus on improving outcomes for children, young people, and their families, based on a shared understanding of well-being

- A common approach to gaining consent and to sharing information where appropriate

- An integral role for children, young people, and families in assessment, planning, and intervention

- A coordinated and unified approach to identifying concerns, assessing needs, and agreeing on actions and outcomes, based on the Well-being Indicators

- Streamlined planning, assessment, and decision-making processes that lead to the right help at the right time

- Consistent high standards of cooperation, joint working, and communication where more than one agency needs to be involved, locally and across Scotland

- A Named Person for every child and young person and a Lead Professional (where necessary) to coordinate and monitor multi-agency activity

- Maximizing the skilled workforce within universal services to address needs and risks as early as possible

- A confident and competent workforce across all services for children, young people, and their families

- The capacity to share demographic, assessment, and planning information electronically within and across agency boundaries

Under the GIRFEC approach, all agencies and all practitioners would be responsible for children's development and their "total well-being" (Coles et al. 2016), working in collaboration:

When assessment, planning and action are needed, practitioners can draw on the Getting it right for every child National Practice Model, which can be used in a single or multi-agency context. (Scottish Government 2016)

Assessments

The Scottish Government's National Practice Model (2016) emphasises the need for assessment to be appropriate, proportionate and timely.

Assessment in social work is defined by Milner et al. (2015, p.2) as a five stage process:

- Preparing for the task

- Collecting data, including perceptions of the service user, the family and other agencies of the problem and any attempted solutions

- Applying professional knowledge (practice wisdom as well as theory) to seek analysis, understanding or interpretation of the data

- Making judgements about the relationships, needs, risks, standards of care or safety, seriousness of the situation, and people's capacities and potential for coping or for change (is the progress good enough?)

- Deciding and/or recommending what is to be done; plus how, by whom and when, and how progress will be reviewed

The practice of integrated assessments in the UK stems from a perceived need for improvements in interagency working and information sharing:

The stronger the tradition of good working relationships both within and between agencies, the quicker progress is made in improving children's outcomes. (Gilligan and Manby 2008)

Integrated assessments have been introduced in Scotland, with the goal of improving children's' outcomes. For example, in Lanarkshire (2012), the stated purpose of the Integrated Assessment and Child's Plan is to:

- Establish a common language that is accessible to children, young people, families and all practitioners

- Support consistency in the practice of involving children, young people and families in decisions that affect their lives

- Identify and manage risk

- Help children and young people, families and agencies understand the strengths and pressures in their lives and what might help

- Establish a co-ordinated, structured, streamlined and simplified process of information gathering, analysis and decision making which increases efficiency and reduces duplication across agencies

- Ensure that all relevant information relating to a child's unique situation is considered and supports robust decision making and planning

- Establish a common framework to agree the desired outcomes and the actions necessary to achieve them

- Empower all participants to contribute fully to the process of assessment, planning and review

- Break down unnecessary professional barriers that are not in the interests of children and young people

- Facilitate the practice of sharing information where it is in the best interest of children, young people and families

- Improve the confidence of professionals to fully engage with a process with which they are familiar and use regularly

The following articles have been identified as potentially useful for contextual background to integrated assessment processes and outcomes outwith Scotland.

Lucas, S (2017) A children's space? Participation in multi-agency early intervention. Child & Family Social Work, 22(4), pp.1383-1390 (paywalled or author repository copy embargoed until 27 January 2019)

The common assessment framework provides a model of early intervention, which is familiar in local authorities throughout England, and asserts a participatory framework of child and family engagement. This article draws on data from a research project undertaken in one local authority in the Midlands of England, to explore the experiences of children, young people, and their families, who were engaged in the process of multi‐agency early intervention. The article considers the young people's involvement, including their accounts of attending common assessment framework meetings, and their engagement by practitioners.

The research found that young people's participation was limited. The findings suggest that this is, in part, a response to disciplinary discourses around schooling and attendance. In addition, the narratives of parents and young people showed that under‐resourcing of work with young people meant that the time taken to build relationships and engage them in a process of self‐assessment, planning, and decision making was constrained and rationed. The article concludes that to achieve a participatory children's space, an active and more engaged model of childhood needs to be facilitated by practitioners and parents outside the school‐dominated space found in this study.

Luckock, B et al. (2015) Developing innovative models of practice at the interface between the NHS and child and family social work where children living at home are at risk of abuse and neglect: a scoping review. Child & Family Social Work, 22(4), pp.62-69 (paywalled)

This paper reports the findings of a scoping study, designed to establish the extent to which innovative practice methodologies around integrated working have been implemented and evaluated in England to date. While the evidence to support the effectiveness of specific practice methodologies and contrasting logics of service design and implementation is shown to be very limited still, achieving reliability and legitimacy in the safeguarding relationships established at the service interface seems to depend on the integrity of the dialogue facilitated in each case.

Nethercott, K (2017) The Common Assessment Framework form 9 years on: a creative process. Child & Family Social Work, 22(2), pp.751-761 (paywalled)

Legislation within England states that local authorities should provide services for all those families in need. However, research has identified that regardless of the introduction of strategies to identify need and enhance family support, ongoing barriers to services adhere.

Taking a social constructionist approach, this study explored professionals' experiences of the use of the Common Assessment Framework form. Data were collected in four different local authorities in two phases. Forty‐one professionals from a variety of agencies took part in semi‐structured interviews. Data were analyzed thematically.

Findings demonstrate that the professionals experienced difficulties in working through the Common Assessment Framework process, for example, in completing the form and engaging families. This situation led to the more experienced and knowledgeable professionals utilising creative ways to successfully navigate the 'referral process'. Such creative working practices included the terminology used to complete the form and how the process was 'sold' to parents, so that they could be in a better position to engage parents and complete the Common Assessment Framework form. Because of this, more experienced professionals seem to be able to accelerate the referral process in order to access much needed support services for children and young people.

Stanley, T et al. (2012) A practice framework for assessments at Tower Hamlets children's social care: building on the Munro Review. Practice, 24(4), pp.239-250 (paywalled)

The Munro review of child protection explains in depth the contemporary challenges in delivering statutory child protection services. It notes that complexity, uncertainty and emotional challenges inherent in social work are contemporary issues not resolved through new national guidance or more bureaucratic procedures. Rather, practice needs reforming at the local level. This paper describes an initiative of practice reform - the new practice framework for assessments, developed and implemented in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, as part of the Munro review. The authors suggest that "the new practice framework for assessments is one where the social worker, their supervisor and families can reflexively engage in the child protection issues and work together towards solutions".

Whittaker, KA et al. (2014) A qualitative study of parents' experiences using family support services: applying the concept of surface and depth. Health & Social Care in the Community, 22(5), pp.479-487 (paywalled or author repository copy)

In this paper, a case is made for the application of the two‐part surface and depth concept for understanding how practitioners engage with families and how they might improve the chances of supporting sustainable differences for parents and families. To illustrate, qualitative data from a review of family centre support provided by a north of England local authority are presented. Data were drawn from interviews with parents (n = 18, recruited following a survey of all those registered with the service during April–May 2009) and discussions with family centre support workers (n = 4), and following thematic analysis, three dominant themes emerged – resources available, staff approach and real life – which were appraised in the light of the surface and depth concept.

Findings include that much of the work with parents effectively dealt with pressing needs. This felt gratifying for both parent and worker and supported immediate service engagement. However, each noted that the more complex issues in parents' lives went unchallenged and thus the sustainability of progress in terms of parenting practice was questionable. A strengths focused approach by staff that understood needs in the context of parents' real‐life circumstances was important to parent engagement. Thus, longer term benefits from family support require practitioners to work with parents to problem solve immediate issues while also digging deeper to acknowledge and seek to resolve the more complex challenges parents face in their real lives.

Child and family experiences of assessment

Understanding how parents experience statutory child protection intervention is important for professionals, agencies and policy makers to enable services to develop intervention practices that create the conditions for constructive engagement, meaningful participation and positive outcomes for both parents and children (Dumbrill, 2006 in Jackson et al. 2017). Evidence suggests that many practices can be distressing and traumatic for parents (Jackson et al. 2017). Understanding this issue may be the starting point in reconsidering aspects of processes that negatively influence engagement with and participation of parents (Jackson et al. 2017).

The studies below have been identified as relevant research articles exploring the experiences of children and families in assessment and involvement in child protection processes more widely.

Buckley, H et al. (2011) 'Like walking on eggshells': service user views and expectations of child protection. Child and Family Social Work, 16(1), pp.101-110 (paywalled or author copy)

This paper reports on a study of service users' views on Irish child protection services. Qualitative interviews were conducted with 67 service users, including young people between 13 and 23. The findings showed that despite refocusing and public service management reforms, service users still experience involvement with the services as intimidating and stressful and while they acknowledged opportunities to participate in the child protection process, they found the experience to be very difficult. Their definition of 'needs' was somewhat at odds with that suggested in official documentation, and they viewed the execution of a child protection plan more as a coercive requirement to comply with 'tasks' set by workers than a conjoint effort to enhance their children's welfare. As in previous studies, the data showed how the development of good relationships between workers and service users could compensate for the harsher aspects of involvement with child protection. In addition, this study demonstrated a high level of discernment on the part of service users, highlighting their expectation of quality standards in respect of courtesy, respect, accountability, transparency and practitioner expertise.

Cortis, N (2007) What do service users think of evaluation? Evidence from family support. Child & Family Social Work, 12(4), pp.399-408 (paywalled)

This paper considers how service users' perspectives can help improve the performance indicators that inform child and family service funding, management and planning. Qualitative research, conducted in family support contexts in New South Wales, Australia, identifies five user‐defined domains upon which indicators can be based. As well as showing how parents judge service quality and outcomes, the findings also show how they experience data collection, and how they prefer to participate in the routine performance measurement and monitoring that informs child and family welfare provision.

Darlington, Y et al. (2012) Parents' perceptions of their participation in mandated family group meetings. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(2), pp.331–337 (paywalled or author copy)

In many developed countries, the right of parents involved in child protection to participate in decision-making is becoming incorporated into legislation and policy. In this article, we report findings from semi-structured interviews with 10 parents (5 mothers and 5 fathers) who participated in formal child welfare decision-making forums (Family Group Meetings) in Brisbane, Australia. The interviews focused on parents' experiences of the meetings, including factors that promote or inhibit participation. The themes of feeling respected by professionals, feeling that one's opinions were heard, and being supported at the meeting were all associated positive experiences of participation, and conversely, those parents who reported overall negative experiences spoke of not feeling respected, not having their opinions heard and not being supported during the meeting. Overall, parents demonstrated a relatively sophisticated understanding of the process; these findings suggest that parents have the capacity to participate meaningfully in child welfare decision-making forums, especially when given adequate support.

Dumbrill, GC (2006) Child parental experience of child protection intervention: a qualitative study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30, pp.27-37 (paywalled or author copy)

This paper explores the ways in which parents experience and negotiate child protection intervention. A qualitative grounded theory approach was used. In-depth qualitative interviews explored the experiences of 18 parents who had received child protection services. Grounded theory methods were used to build a model representing the ways these parents perceived and reacted to intervention. The ways parents perceive workers using power was shown to be the primary influence shaping parents' views of intervention and their reactions to it. Two perceptions of power emerged: parents perceived power being used over them as a form of control or power with them as a form of support. Three ways of responding to intervention emerged: parents fought workers by openly opposing them, "played the game" by feigning co-operation, or worked with them in collaborative relationships. Parents experiencing power being used over them tended to fight or play the game while parents experiencing power being used with them tended to work with intervention. No evidence was found linking case type (non-voluntary or voluntary cases) to whether parents perceived power being used by workers over them or with them.

Hollinshead, DM et al. (2015) Influence of family, agency, and caseworker dynamics on caregivers' satisfaction with their child protective services experience. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 9(5), pp.463-486 (paywalled)

This research tests a conceptual framework developed to examine dynamics between caregiver, agency, and caseworker factors that are assumed to impact caregiver engagement. Data from a randomized control study and structural equation modeling methods were used to explore the influence of these factors on caregiver satisfaction with their CPS experience. The results indicate that receipt of alternative response, caregivers' ratings of their caseworker's interaction style, and caregivers' positive emotional response influenced satisfaction with their intervention experience, while negative emotional responses did not.

Holmes, L and McDermid, S (2014) The Common Assessment Framework: the impact of the lead professional on families and professionals as part of a continuum of care in England. Child & Family Social Work, 21(4), pp.530-538 (paywalled)

This paper utilizes data gathered as part of an exploratory study to assess the costs and impact of the Common Assessment Framework (CAF), to examine the impact that the lead professional role had on families and workers. The study found that both families and workers believed the lead professional to be central to the CAF process, providing a range of support, coordinating multi‐agency responses to need and acting as a single point of contact between families and workers.

The paper highlights the need for consideration to be given to inter‐agency working, data sharing, training for workers and the capacity implications for those taking on the role. The extent to which the lead professional might be more integrated into the continuum of support for vulnerable children and families is also examined. The paper highlights the need to consider the lead professional's role in not only preventing the need for more intensive services, such as those provided by statutory social work, but also maintaining outcomes achieved once a child protection plan is closed, or a child is reunified with his or her birth family after a period of being in care. The implications of the findings for policy and practice are discussed.

Ghaffar, W et al. (2012) Exploring the experiences of parents and carers whose children have been subject to child protection plans. British Journal of Social Work, 42(5), pp.887-905 (paywalled)

This study explored the experiences of forty-two families in three local authorities in Northern England in 2009. Out of the families involved, twenty-five highlighted domestic abuse and mental health issues, and twenty-one identified drug or alcohol issues as impacting negatively on their parenting. Most parents had positive experiences of help with drug/alcohol issues, and many were motivated to overcome their problems by a desire to continue (or resume) looking after their children. Parents experiencing domestic abuse or allegations of child sexual abuse were less positive. Parents had a clear understanding of the responsibilities of child protection social workers. Three-quarters of families were able to identify positive qualities in the professionals who supported them; they had a positive view of inter-agency communication. They did not expect an equal role in decision making. Parents' and professionals' views tended to converge over time. Absorbing information at the start of the process was difficult for many parents. Most found case conferences daunting and intimidating, and reports often reached them too late. Parents were critical of assessments using a deficit model; they received too little therapeutic help for themselves and their children.

Jackson, S et al. (2017) Parental participation in statutory child protection intervention in Scotland. British Journal of Social Work, 47(1), pp.1445-1463 (paywalled)

This paper presents the findings of a small-scale qualitative study which explored the experiences of twelve parents who were, at the time of the study, subject to statutory child protection intervention measures in Scotland. Parents reported intervention experiences as simultaneously negative and positive. The early stages of intervention and child protection case conferences were experienced as particularly distressing and confusing. The importance of the client–worker relationship emerged as central to meaningful participation and positive outcomes.

Lucas, S (2017) A children's space? Participation in multi‐agency early intervention. Child & Family Social Work, 22(4), pp.1383-1390 (paywalled)

The common assessment framework provides a model of early intervention, which is familiar in local authorities throughout England, and asserts a participatory framework of child and family engagement. This article draws on data from a research project undertaken in 1 local authority in the Midlands of England, to explore the experiences of children, young people, and their families, who were engaged in the process of multi‐agency early intervention. The article considers the young people's involvement, including their accounts of attending common assessment framework meetings, and their engagement by practitioners. The research found that young people's participation was limited. The findings suggest that this is, in part, a response to disciplinary discourses around schooling and attendance. In addition, the narratives of parents and young people showed that under‐resourcing of work with young people meant that the time taken to build relationships and engage them in a process of self‐assessment, planning, and decision making was constrained and rationed. The article concludes that to achieve a participatory children's space, an active and more engaged model of childhood needs to be facilitated by practitioners and parents outside the school‐dominated space found in this study.

MacQueen, S et al. (2007) Support and services for parents: a review of the literature in engaging and supporting parents. Scottish Government Social Research (pdf)

This literature review aims to draw together existing knowledge on assessing and evaluating parenting interventions. It explores approaches to engaging and supporting parents identified that parents reported feeling powerless when workers did not take on board their point of view or empathise with the difficulties they were facing. Where workers took steps that parents felt were inappropriate to their needs, parents reported feeling unable to challenge the preconceptions of the worker or the action plan formulated from their assessment.

Mellon, M (2017) Child protection: listening to and learning from parents. Iriss Insight 39 (website and pdf)

Key points

- Research points to parents' experiences of child protection investigations and associated processes as often being unpleasant and disrespectful

- Learning from parents' experiences needs to be incorporated into everyday work if practice is to be improved

- Family group conferencing, advocacy and other person-centred and strengths-based initiatives offer opportunities for less adversarial and more constructive approaches

- Engagement with new forms of parent self-organisation, including online, and the incorporation of peer advocacy in training and in improving practice, offer opportunities to encourage positive changes at all levels

O'Connor, L et al. (2014) Perspectives on children's experiences in families with parental substance misuse and child protection interventions. Children and Youth Services Review, 38, pp.66-74 (paywalled)

This paper presents data from a Welsh mixed methods study of a service for families whose children were at risk of entering out-of-home-care due to parental substance misuse (out-of-home care is referred to as Local Authority Care in the UK). Three sources of data are drawn on to focus on the experiences of children and young people: interviews with a small number of young people, interviews with parents where they discussed their children's experiences and measures of child and family functioning. The inclusion of qualitative data from two generations of families illustrates the complex interwoven nature of children's and parents' experiences. Analysis suggests that key messages for practitioners are the need to engage with substance using families in ways that avoid unhelpful binaries focusing on either the child's or the adult's needs. Children and young people may benefit from brief interventions during a period of crisis and longer term interventions which address cumulative effects and attachment complexities and promote sources of resilience.

Platt, D (2008) Care or control? The effects of investigations and initial assessments on the social worker‐parent relationship. Journal of Social Work Practice, 22(3), pp.301–315 (paywalled)

This paper presents qualitative research findings regarding the effects of more coercive and less coercive interventions on relationships between social workers and parents. Its context is the use, in England, of investigations of alleged child abuse (more coercive) versus initial assessments (less coercive, and potentially leading to family support services). Methods were based on 23 case studies involving interviews of both parent and social worker. The paper concludes that the less coercive initial assessments, combined with child welfare concerns that were perceived as less serious, provided the context for good working relationships between parent and worker. However, it is suggested that these conditions were not a prerequisite for good relationships. Worker skill was of significant importance, and good relationships were seen to be possible in a variety of procedural contexts.

Smithson, R and Gibson, M (2016) Less than human: a qualitative study into the experience of parents involved in the child protection system. Child and Family Social Work, 22(2), pp.565-574 (paywalled)

This paper reports on the findings from a qualitative study into the experiences of parents who were involved in the English child protection system in 2013. Seventeen in‐depth interviews were conducted involving 19 parents and/or partners, and a framework approach was used to analyse the data. There were positive experiences of individual social workers and some positive experiences of the child protection system. However, the overwhelming theme of the parents' experiences was that the system was uncaring, inflexible and for some harmful to both themselves and their children. Despite being included in the child protection process, parents felt they were not afforded the same rights as a participant, as a decision‐maker or as a partner in seeking to improve the situation. The threat of consequences silenced parents who felt unable to speak out or challenge the things they disagreed with or coerced others into signing agreements they did not agree to. Such experiences related to a sense that they were being treated as 'less than human'. These findings are considered within the context of recent reforms within the English child protection system.

Good practice

This section presents examples from research and practice knowledge around what may work to make the assessment process more accessible and pleasant for children and families.

In addition to the research articles identified below, research findings and good practice recommendations reported in previous Iriss ESSS Outlines on frameworks for child participation in social care (Allcock 2018), children experiencing interparental coercive control (Smith 2018) and child sexual abuse and good practice for social workers (Smith 2017) may be of relevance.

Assessment and frameworks

British Association of Social Workers (2014) Putting critical analysis into social work practice (website)

This seminar explored the meaning of critical analysis and how to make assessments more analytical. It may be of interest to social work students and practitioners at all levels of experience in adults, mental health and children's practices. The seminar was organised in response to the identified shortfalls in analytical skills of social workers – Munro's review of children's social work found practitioners are good at gathering information but find it difficult to interpret.

Children's Workforce Development Council (2009) The Common Assessment Framework for children and young people: a guide for practitioners (pdf)

This guidance replaces the Common Assessment Framework for children and young people: practitioners' guide originally published by the DfES in 2006 and reprinted in September 2007. It remains non-statutory guidance. The new guidance has been updated and re-titled in order to reflect policy developments and include revisions identified in consultation with practitioners and managers across the children and young people's workforce. It also seeks to link together the processes and tools mentioned above, to show how collectively they provide a package of support to help practitioners and managers implement integrated working in their practice.

It includes guidelines for good practice around areas including:

- CAF and integrated working

- How to do a common assessment

- Information sharing, consent and confidentiality

Children's Workforce Development Council (2009) The Common Assessment Framework for children and young people: a guide for managers (pdf)

This guidance replaces the Common Assessment Framework for children and young people: managers' guide originally published by the DfES in 2006 and reprinted in September 2007. It remains non-statutory guidance. The new guidance has been updated and re-titled in order to reflect policy developments and include revisions identified in consultation with practitioners and managers across the children and young people's workforce. It also seeks to link together the processes and tools mentioned above, to show how collectively they provide a package of support to help practitioners and managers implement integrated working in their practice.

It includes guidance on areas including:

- Role and responsibilities of managers

- Operating the CAF across children's services

Collins, E and Daly, E (2011) Decision making and social work in Scotland: The role of evidence and practice wisdom. Iriss (pdf)

This report presents the results of a small qualitative study undertaken between February and March 2011. It considers the role of evidence in decision making around risk in social work and what affects this process. It investigates the following issues:

- What constitutes evidence for social workers?

- How do social workers make sense of the multiple sources of evidence available to them?

- Does decision-making change in situations where the evidence available is not of ideal quality or the circumstances around the investigation are limiting?

- What, if anything, affects decision-making other than the available

- evidence?

- How aware are social workers of their own decision-making processes?

- What can the above issues tell us about practice wisdom?

Devine, L (2015) Considering social work assessment of families. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 37(1), pp.70-83 (open access)

This article considers the debates that have emerged in relation to the use of the Framework for the assessment of children in need and their families in England and concludes that insufficient consideration has been given to evaluating assessment as an appropriate measure of need and risk. The author argues that wider provision of non-assessed universal services would reduce the need for assessment.

Edinburgh, Lothian and Borders Executive Group Public Protection Partnership Office (2013) Getting it right for children and families affected by parental problem alcohol and drug use: guidelines for agencies in Edinburgh and the Lothians. Child Protection West Lothian (pdf)

Pages 48-50 of this guide include recommendations for integrated assessment processes, outcomes of integrated assessment and Child's Plans, reproduced below:

Integrated assessment

8.5.1) An integrated assessment should be undertaken on all parents/expectant parents with problem alcohol and/or drug use where additional needs or concerns have been identified about the welfare of a child/young person. Practitioners should refer to Getting it right for every child good practice guidance on 'Integrated Assessments' and should use the supplementary assessment tool 'Framework for Assessment: Children and families affected by parental problem alcohol and/or drug use' (see Appendix I) to aid the assessment process.

8.5.2) Documented consent to share information should be obtained from parents before contacting other agencies. The reasons for contacting other agencies should be clearly explained to parents and recorded.

8.5.3) If the parents object to this course of action, the Named Person will need to make a judgement as to whether a formal child protection referral is necessary in the interests of the child/young person, and take action to this end.

8.5.4) When organising an integrated assessment and multi-agency meeting, the Named Person should:

- Explain to the parents the reasons for the meeting

- Invite the parents to the meeting, and any child/ young person when deemed appropriate

- Maintain and/or increase the level of proactive support offered to, and contact with the parent and child/young person, as this is likely to be a period of anxiety for them.

8.5.5) The purpose of an integrated assessment of a child/ young person and family is to:

- Identify a child/young person's needs within his or her family and community

- Identify the needs of other family members including parents, siblings and significant others involved with the family

- Describe any concerns or risks to the child/young person's health, development and welfare

- Help the family find ways of solving problems to ensure that the child/young person's needs can be properly met

- Decide what help or services, if any, agencies should provide.

8.5.6) A number of practitioners should make a contribution to the assessment of need and take part in any meeting/discussions about the family. These might include:

- Social Work staff and Council employees

- Education/Community Education staff

- NHS employees including medical staff, allied healthcare professionals and psychologists, nursing and midwifery staff, pharmacists and dentists

- Alcohol and/or drug service practitioners

- Police - including Public Protection Unit and community police officers Housing/Leisure organisation staff Third Sector agency staff Youth services staff

8.5.7) The Named Person's agency should provide the administrative arrangements in support of the completion of the integrated assessment.

8.5.8) The integrated assessment should normally be completed within 6 weeks and for expectant parents, by 24 weeks' gestation. The Named Person should ensure that the assessment includes at least one home visit.

8.5.9) The integrated assessment should be fully recorded using Getting it right for every child documentation (according to local guidance) and retained in the adult and child's notes. Copies of the assessment and its outcome should be sent to the parents and all practitioners involved with the family

Outcomes of Integrated Assessment

The integrated assessment should result in two possible outcomes:

8.6.1) Additional needs identified – the child/young person is in need of care and attention and the family would benefit from a Child's Plan, coordinated by an identified Named Person (single agency involvement) or Lead Professional (multi-agency involvement). Refer to Getting it right for every child practice guidance and 'Roles and Responsibilities' (Section 7).

8.6.2) Risk identified – the child/young person is at risk of harm and the grounds for concern merit an Inter- agency Referral Discussion (IRD) between the key agencies (social work, paediatrician on call for child protection and police), under the Child Protection Procedures.

- The Named Person (if single agency) or Lead Professional (multiagency support) should document and communicate the outcome of the integrated assessment to the professionals and agencies from whom information had been requested.

- All actions taken, decisions and evidence to back up the conclusion of the integrated assessment should be clearly recorded in the adult and child/ young person case notes or secure electronic shared assessment record e.g. Maternity TRAK, Community TRAK, Single Shared Assessment, SWIFT.

HM Government (2013) Working together to safeguard children: a guide to interagency working (pdf)

Statutory guidance on inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children. This guidance covers the legislative requirements and expectations on individual services to safeguard and promote the welfare of children; and a clear framework for Local Safeguarding Children Boards (LSCBs) to monitor the effectiveness of local services in England.

Hood, R (2016) A conceptual review of interprofessional expertise in child safeguarding. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(4), pp.493-498 (paywalled or author preprint)

This article develops the concept of interprofessional expertise in order to explain how practitioners become more proficient at working with others to manage complex child welfare issues. Key principles are outlined with reference to relevant theoretical frameworks, including models of skill acquisition. The article concludes by discussing some potential implications for future research and contemporary developments in child safeguarding practice.

Ingram, R and Smith, M (2018) Relationship-based practice: emergent themes in social work literature. Iriss Insight 41 (pdf or website)

Key points

- There are compelling philosophical, policy and practice reasons to put relationships at the heart of social work

- The importance of relationships is increasingly recognised in 'people work' but especially in social work and social care, across all domains of practice • Effective relationships are central to successful outcomes

- Current policy directions in Scotland are rooted in the need for effective personal/ professional relationships

- Relationships are complex, requiring an awareness of 'self' and the negotiation of interpersonal boundaries

- Current practice cultures can make it difficult to practice in properly relational ways and would require a radical shift for issues of power, agency and status to be addressed

Iriss (2011) Making sense of child and family assessment - Duncan Helm (audio and slides)

Duncan Helm focuses on how practitioners carry out analysis in child care family assessments. Theories of judgement are applied to help understand the processes through which practitioners make sense of information in assessments. In particular the presentation focuses on the nature of judgements made under pressures of time and conditions of uncertainty. Frameworks for practice are considered and contemporary literature is explored to identify what helps and what hinders accurate, empathetic assessments of risk and need in child welfare and protection.

Recorded Scottish Child Care and Protection Network. Contemporary issues in child protection seminar, Perth Concert Hall.

Jackson, S et al. (2017) Parental participation in statutory child protection intervention in Scotland. British Journal of Social Work, 47(1), pp.1445-1463 (paywalled)

This paper presents the findings of a small-scale qualitative study which explored the experiences of twelve parents who were, at the time of the study, subject to statutory child protection intervention measures in Scotland.

Recommendations from this study of parents' experiences of child protection interventions include:

- More thoroughly consider practices with parents during the early stages of intervention

- Understand more thoroughly how to move parents towards a more informed and meaningful trajectory

- Reduce authoritarian practices in case conferences, for example by making changes to the courtroom style of meeting rooms and have professionals enter the conference after parents to reduce feelings of intimidation

- Enable parents to respond to the individual commentaries of different professionals to enable more effective parental contributions

Milner, J et al. (eds.) (2015) Assessment in Social Work. New York: Palgrave (4th ed.) (Book available from NHS Libraries)

This core textbook provides structured, practical guidance on how to approach assessment. The authors provide the theory behind assessment and practice examples. It includes chapters on strengths-based approaches and assessment in children's services.

Millar, M and Corby, B (2006) The framework for the assessment of children in need and their families: a basis for a 'Therapeutic' Encounter? British Journal of Social Work, 36(1), pp.887–899 (paywalled)

This paper examines the Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families, implemented by local authorities in England in 2001. Using interviews with service users and social workers, the authors found that although not perfect, some service users found aspects of their assessment to be personally beneficial. This is discussed in detail, reaching the conclusion that using the framework can be therapeutic (whilst explicitly at no stage implying that service users' needs and troubles are generally psychological in origin, rather using the term in the sense that benefits can be enhancements to personal understanding or well-being).

The authors suggest that "part of what some service users considered helpful was related to the format of the new framework, and not only to its use in the hands of skilful and experienced practitioners". One of the identified strengths of the framework was that part of the new framework's format for assessment had improved communication in ways service users welcomed. It is suggested that prescriptions for practice, as present in the framework, can be helpful to practitioners. A key point emphasised is that practices such as forms and formats, that may seem to be for the purposes of imposing bureaucratic control may in fact serve to reduce power differentials.

In terms of good practice, the authors argue that forms and formats have a contribution to make, but they should be used for specified and well-understood purposes and that sufficient time should be allocated to meet intended goals.

NSPCC (2014) NSPCC Factsheet: Assessing children and families (pdf)

This factsheet provides good practice recommendations including:

Good assessments must be purposeful and timely. Practitioners need to be clear about why they are carrying out assessments and what it is they wish to achieve. This information should be shared with families from the outset.

Assessments gather information about a child and their family which will help the practitioner to:

- Understand the child's needs and assess whether those needs are being met by the family and/or any services already provided

- Analyse the nature and level of any risks facing the child as well as identifying protective factors

- Decide how to support the family to build on strengths and address problems to assure the child's safety and improve his or her outcomes.

Pattoni, L (2012) Strengths-based approaches for working with individuals. Iriss Insight 16 (website and pdf)

This Insight provides an overview of the research evidence on effective strengths based approaches for working with individuals and presents selected illustrative examples.

Key points

- Strengths-based approaches value the capacity, skills, knowledge, connections and potential in individuals and communities

- Focusing on strengths does not mean ignoring challenges, or spinning struggles into strengths

- Practitioners working in this way have to work in collaboration - helping people to do things for themselves. In this way, people can become co-producers of support, not passive consumers of support.

- The evidence for strengths-based approaches is difficult to synthesise because of the different populations and problem areas that are examined in the literature

- The strengths approach to practice has broad applicability across a number of practice settings and a wide range of populations

- There is some evidence to suggest that strengths-based approaches can improve retention in treatment programmes for those who misuse substances

- There is also evidence that use of a strengths-based approach can improve social networks and enhance well-being

Samsonsen, V and Turney, D (2016) The role of professional judgement in social work assessment: a comparison between Norway and England. European Journal of Social Work, 20(1), pp.112-124 (paywalled or author manuscript)

This paper explores the different ways in which professional judgement is understood and addressed in the English and Norwegian systems and asks what we can learn from them in terms of best assessment practice. Acknowledging child protection as a 'wicked problem', we propose a model of Grounded Professional Judgement based on notions of epistemic responsibility and accountability to support the exercise of professional judgement in situations of uncertainty.

Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) (2015) What makes a good assessment? (website)

As part of work around the Care and Support (Assessment) Regulations 2014, SCIE asked a group of people using and receiving services, and a group of carers, to share their experiences of being assessed, and tell them what a social worker could do to make an assessment better. Although related to prevention services, the application of the strengths-based approach to the recommendations may be relevant in supporting individual's independence, resilience, ability to make choices and wellbeing in other contexts such as child protection.

The answers from participants highlighted the following areas:

Be flexible and perceptive of an individual's situation and needs around the assessment process:

- Allow for a break in the assessment if needed so that the user doesn't become overwhelmed

- Have an understanding of the person's condition

- Repeat facts to confirm they're accurate and you have noted them down correctly

Follow a holistic/whole-person approach:

- Look at the whole community and be aware of the support available from that community

- Focus on a whole-life approach not just a person's care needs.

- Focus on outcomes

- Consider how the individual might contribute to the local community, and hence be better integrated in the wider society around them

Be professional, honest, open and approachable:

- Make sure you listen

- Let people speak, even if their assessment is taking place with an advocate present

- Be clear that you can't fix everything in one session and that this is an ongoing process

- Build trust with people

- Be conversational without too much direct questioning – people will open up more and provide more detailed answers

- Be friendly but be aware of the difference between 'friend' and 'friendly'

- Be clear about who is making any given decision. If you need to take your findings to your manager then be clear about this from the start

- Let the individual know that they have a right to appeal against the outcome of the assessment

- Explain the possible outcomes

- Don't use jargon

- Perform your assessment as an intervention, so that the individual will benefit from the process itself no matter what the outcome is

Scottish Government (2012) A guide to Getting it right for every child (website)

This guide is in two main sections:

- The first section is about the foundations that underpin the Getting it right for every child approach

- The second describes how practitioners can use the GIRFEC approach and in particular the National Practice Model to help bring about the changes across culture, systems and practice that will help children and young people achieve their full potential

Walker, G (2018) Working together for children: a critical introduction to multi-agency working (book)

This book provides a factual and analytical introduction to the systems and processes of multi-agency work with children and families. It is for trainee practitioners in childcare, education, social work and health care, and for those going on to work, or already working, in such settings who are looking to be more effective practitioners.

Reflection on practice is a theme running throughout the book. To assist readers with this, there are two types of feature: information boxes, giving further factual details of particular areas related to multi-agency work; and reflective exercises containing case studies, vignettes or statements, followed by questions designed to stimulate reflection on issues raised in the text.

Wilson, P et al. (2018) International variation in programmes for assessment of children's neurodevelopment in the community: understanding disparate approaches to evaluation of motor, social, emotional, behavioural and cognitive function. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, pp.1-12 (paywalled or author manuscript)

This article critically examines the history, underlying philosophy, content and delivery of programmes for child development assessment in five countries with comprehensive publicly funded health services (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Scotland and Sweden). The specific focus of this article is on motor, social, emotional, behavioural and global cognitive functioning including language.

The authors find variations in developmental surveillance programmes which they argue are substantially explained by historical factors and gradual evolution, although Scotland has undergone radical changes in approach. No elements of universal developmental assessment programmes meet World Health Organization screening criteria, although some assessments are configured as screening activities. The roles of doctors and nurses vary greatly by country as do the timing, content and likely costs of programmes. Inter-professional communication presents challenges to all the studied health services. No programme has evidence for improved health outcomes or cost effectiveness.

The authors conclude that developmental surveillance programmes vary greatly and their structure appears to be driven by historical factors as much as by evidence. They argue that consensus should be reached about which surveillance activities constitute screening, and the predictive validity of these components needs to be established and judged against World Health Organization screening criteria. They also argue that costs and consequences of specific programmes should be assessed, and the issue of inter-professional communication about children at remediable developmental risk should be prioritised.

Involving children and families

The following resources present evidence about what works well and what aspects to consider in involving children and families in assessment processes and other relevant areas of children's services.

Crowther, K and Cowen, G (2011) Effective relationships with vulnerable parents to improve outcomes for children and young people: final study report. Action for Children (pdf)

The focus of this research was to develop a skills framework that would define the key aspects of effective professional relationships and the competencies required to achieve them. Aspects of the findings touch on experiences of the assessment process and recommendations for practice are made, including around:

- The importance of comprehensive assessment processes

- Using a strengths-based approach

- How being reliable and proactive helps build trust and respect

- How keeping parents informed builds trust

- How recognising positive achievements is important in maintaining a good relationship with parents

Dalrymple, J (2002) Family group conferences and youth advocacy: The participation of children and young people in family decision making. European Journal of Social Work, 5(3), pp.287–299 (paywalled)

The notion of independent advocacy does not sit easily with the principles of Family Group Conferences (FGC). The integrity of conferencing is in the competence of family members to make their own decisions. The challenge of enabling the voice and agency of children and young people within their own family networks however is formidable. The familial nexus can be as institutionally excluding as any other adult forum. This paper focuses on the work of a FGC project in Wiltshire, England, which used a small grant to provide independent advocacy for children and young people involved in conferences. Drawing on an evaluation of the project, the article argues that distinguishing children and young people's power from parental and professional power permits their empowerment through the use of advocacy.

Featherstone, B et al. (2014) Re-imagining child protection: towards humane social work with children and families. Bristol: Policy Press (book available from NHS Libraries)

Raising a number of critical questions, Brid Featherstone, Susan White and Kate Morris challenge a child protection culture that they see as becoming increasingly authoritarian. Calling for a family-minded practice of child protection, they argue that children should be understood as relational beings and that greater sensitivity should be paid to parents and the needs they have as a result of the burdens of childcare. They argue that current child protection services need to ameliorate, rather than reinforce, the many deprivations that parents engaged in their systems face. Bringing together authors who combine a wealth of experience in both scholarship and practice, this book provides a sensitive reassessment of a critical point of contact between governments and families. (Book blurb)

Gallagher, M et al. (2011) Children and families' involvement in social work decision making. Children & Society, 26(1), pp.74-85 (paywalled)

This review summarises the research literature on children's and parents' involvement in social work decision making. Different individuals or groups may have different understandings of participation and related concepts, while differences of age and disability also mediate effective user engagement. The literature highlights common themes in effective participatory practice with both children and their parents. Central to this are the establishment of relationships of trust and respect, clear communication and information and appropriate support to participate.

McGhee, J and Hunter, S (2010) Involving parents in assessment and decision-making (pdf)

This research briefing draws on research that explores the perceptions and experiences of parents involved with child welfare services to highlight some of the key messages for practice that enhance participation.

Key messages

- Quality of the relationship between the practitioner and parents is central to effective engagement and involvement of parents

- Parents value honesty, reliability, good listening skills and practitioners who demonstrate empathy and warmth

- Make explicit use of counselling skills (both generic and adapted to parents with learning difficulties) to develop empathy and increase the potential for more productive relations

- Power differentials should be recognised and taken into account especially when working with resistance

- Explicit discussion with parents of their perceptions of how workers are using their professional power as a means of control or as an element in the support

- Holistic, strengths-based assessment, including family and social networks and methods such as family group conferences can be effective especially in involving fathers and father-figures

- Drawing on the expertise of professionals with experience of working with adults with learning disabilities to maximise their involvement and participation

Platt, D (2012) Understanding parental engagement with child welfare services: an integrated model. Child & Family Social Work, 17(2), pp.138-148 (paywalled)

This paper takes an ecological approach to understanding engagement of parents with services when children may be at risk of abuse/maltreatment. Gaining parental cooperation is a fundamental factor affecting social work interventions, treatment and decision‐making. Based on a review of current literature, the paper adapts the Multifactor Offender Readiness Model to the child welfare context, using insights from other theoretical and empirical work. Parental engagement with child welfare services is portrayed as having behavioural, attitudinal and relationship components, and is determined by internal (service user) and external (policy, programme and worker) factors.

Smithson, R (2015) Engaging parents in child protection. Research in Practice (website)

Birmingham City Council's Strategic Research Team undertook a critical exploration of parents' experiences of the child protection process, with a view to identifying how processes and practice could be improved. In depth interviews were conducted with 19 parents and an e-survey and focus groups were conducted with social work practitioners and principal officers.

Key findings

Parents feel under-prepared for conference meetings, during which professionals decide whether to place their child under protection. They want their social worker's assessment report in advance of meetings and the opportunity to go through this with both the social worker and the chair.

Parents want to be involved more and heard in conferences. Parents were frustrated when they had to wait until all the professionals had given their reports before they could respond. Parents also felt daunted by conference and at times 'ganged up on'.

All parents had access to their Plan, but they wanted this document to be more user-friendly. In particular they called for fewer actions to form a more realistic agenda for change and clearer specifications in terms of timescales, responsibilities, and consequences of inaction and action.

They want to have a better understanding of the level of risk in their family, progress made towards reducing this, and what needs to change before CP conditions would be reduced and/or removed.

Often parents welcomed the support they received as a result of the CP process, but did not have a sufficient understanding of how actions, often in the form of courses, would lead to their family coming off CP.

Some parents had positive experiences of working with social workers, half said they had built an effective relationship with them; others wanted to see improvements. Parents want: hands-on support, for social workers to take time to listen and not to pre-judge families on reports given to them, for social workers to take the time to get to know the family, fewer changes in social workers and more empathy.

Many parents were subject to separation arrangements and felt staff should have a greater appreciation of the negative impact this has on both parents and children emotionally and mentally. Parents wanted more focus on when arrangements would be stepped down and clearer timescales for bringing families back together.

The research also highlighted that agencies should be playing a fuller role in CP. Parents wanted more regular and honest updates (outside of conference), particularly from schools, with regards to issues experienced by their children and addressing these collaboratively.

Platt, D and Riches, K (2016) Assessing parental capacity to change: the missing jigsaw piece in the assessment of a child's welfare? Children and Youth Services Review, 61, pp.141-148 (open access)

This paper presents a framework for assessing parental capacity to change, for use by social workers when a child is experiencing significant harm or maltreatment. It reports on part of the work of a knowledge exchange project involving the University of Bristol and three local authorities in South West England. The availability of assessment models addressing capacity to change, in both social work practice and the academic literature, was found to be limited. At the same time, the importance of such an assessment is significant, in terms of the lives of children affected. Two particular approaches were examined, the assessment of actual attempts to change parenting behaviour, and how behaviour change theory can help understand barriers or facilitators to change such as individual motivation, or habits and automatic responses. The development of an assessment approach is outlined, based on these two key features. It is argued that this type of assessment helps fill an important gap in social work theory and practice.

Other considerations

Electronic information systems

The following articles raise interesting contextual considerations around the ethical and appropriate use of electronic information systems in social work and related areas.

Devlieghere, J et al. (2017) Policy rationales for electronic information systems: an area of ambiguity. The British Journal of Social Work, 47(5), pp.1500–1516 (open access)

This research presents the findings of semi-structured interviews with policy actors (directors, policy advisers and staff members) in the field of CWP in Flanders who were asked about their rationales for installing EIS. Rationale included administrative, policy, care and economic reasons. The authors discuss the critical attitudes expressed by participants concerning the usefulness of EIS, including hopes that practitioners would move back and forth between governmental demands and day-to-day realities, to establish a more responsive social work. The authors discuss the ambiguity of this situation and the complexities surrounding it.

Gillingham, P (2018) Developments in electronic information systems in social welfare agencies: from simple to complex. The British Journal of Social Work, 41(0), pp.1-12 (open access)

In this article, drawing from ethnographic research about IS implementation and evaluation with a number of social welfare agencies, two different approaches—one simple and one complex—to designing and using IS in social welfare agencies are presented. The advantages and disadvantages of each approach, as emerged from discussions with research participants, are explored. The aim of the article is to assist both decision makers and practitioners in social welfare agencies to clarify their needs in relation to how future IS are designed and used.

Gillingham, P (2016) Electronic information systems to guide social work practice: the perspectives of practitioners as end users. Practice, 28(5), pp.357-372 (paywalled)

Evaluations of electronic information systems (IS) being used in social work agencies in England and Australia have been highly critical of their effects on frontline social work practice. Attention is now turning to how IS might be redesigned and used in the future. One particular development is the inclusion of particular practice frameworks in the design of IS, in order that, when practitioners use them, practice is shaped and guided. With the aim of improving social work practice, the IS is intended to act as an 'external expert'. In this article, the findings of a small-scale ethnographic study of an IS that incorporates the Looking after Children framework for children in out of home care are presented. The challenges of incorporating practice frameworks into IS are discussed.

Gillingham, P (2015) Electronic information systems and human service organizations: the needs of managers, human service organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 40(1), pp.51-61 (paywalled or author copy)

It has been acknowledged that electronic information systems (IS) implemented in human service organizations (HSOs) have undermined frontline practice and privileged the needs of managers over those of practitioners. Attention has turned to how they might be better designed to meet the needs of practitioners, but understanding the needs of managers in relation to IS is also crucial. Based on the findings of ethnographic research, insights are provided into the needs of managers in HSOs in relation to IS. The implications for making effective use of current designs of IS and future IS design are discussed.

Gillingham, P (2015) Electronic information systems and social work: principles of participatory design for social workers. Advances in Social Work, 16(1), pp. 31-42 (author copy)

The introduction of electronic information systems (IS) to human service organizations has been heavily critiqued, most notably for the ways that IS may undermine frontline social work practice. Socio-technical design has been proposed as one way to redesign IS, and a key element of this approach is the involvement of practitioners in the design process. Social workers, though, may be ill-prepared to engage in such processes. Reflecting on the findings of a program of research which aimed to contribute to future designs of IS that support frontline practice, this article aims to provide some guidance for social workers to help them be active and effective participants in the future development of IS.

Surveillance, data security and privacy

The articles presented below address some of the key concerns around the impact of increased use and sharing of personal data in child protection and the risks associated with (accidental or otherwise) misuse of data. It may be relevant to consider these when developing an integrated assessment plan.

NB: information sharing practices rules and recommendations from the Scottish Government are currently under review and should be read in context of the current Children and Young People (Information Sharing) (Scotland) Bill (Scottish Government 2018).

Anderson, R et al. (2006) Children's databases – safety and privacy, a report for the information commissioner. Foundation for Information Policy Research (pdf)

The Foundation for Information Policy Research (FIPR) was awarded a tender by the Information Commissioner to undertake a research project on 'identifying the growth in children's databases and assessing the data protection and privacy implications'. Its aim is to provide the Commissioner with a comprehensive view of current and proposed databases, particularly in the public sector, their extent, their role, and their potential effect on the privacy of individuals. It is also to provide an authoritative basis from which the Commissioner can develop his policy on data protection, and contribute more widely to the debate on this issue, and to public policy generally.

Parton, N (2008) The 'Change for Children' programme in England: towards the preventive-surveillance State. Journal of Law and Society, 35(1), pp.166-187 (paywalled or author copy)

This paper provides a critical analysis of the assumptions that underpin the policy and practice changes to early intervention made following the Children Act 2004. The author argues that the relationships between parents, children, professionals, and the state, and their respective responsibilities, are being reconfigured, and that the priority given to the accumulation, monitoring, and exchange of electronic information has taken on a central significance. They discuss the emergence of what they conceptualise as the 'preventive‐surveillance' state, where the role of the state is becoming broader, more interventive, and regulatory at the same time.

Stoddart, E (2015) The Named Person: surveillance and the wellbeing of children and young people in Scotland. Surveillance & Society, 13(1), pp.102-116 (open access)

This article focuses on the Named Person service, arguing that an attenuated understanding of surveillance by politicians and other stakeholders has contributed to a failure to adequately consider the surveillance dimensions of this new universal provision.