Introduction

This evidence summary seeks to address the following questions relating to gender specific services for women with complex needs:

- How effective (in terms of outcomes and costs) are women specific interventions in addressing complex needs?

- What are the impact of these interventions as preventative strategies in children's services? (e.g. reducing the likelihood of recurrent child protection interventions)

About the evidence presented below

We searched academic databases (ASSIA, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts), Google Scholar and Google, as well as identifying key organisations and searching their websites (including Iriss, NICE, NSPCC and the Scottish Government). The search strategy we used included combinations of terms including adverse childhood experiences, alcohol, child protection, combat, community justice, community services, complex needs, diversion, domestic abuse/violence, drugs, gender differences/differentials, gender responsive/sensitive, health, homelessness, learning disability, mental health, offending behaviour, prevention, refugees, reoffending, social services, substance misuse, trauma informed, women specific and young mothers. We looked for evidence of impact measured and demonstrated in a wide range of ways, including individual and social impact, qualitative and quantitative findings, including social return on investment.

Although we were able to identify a high volume of relevant research, there was an overall lack of research that rigorously demonstrated the effectiveness of women specific interventions in addressing complex needs. Problems with methodology and research quality are one limiting factor of the evidence base. For example, Krahn et al. (2018) identify weaknesses in research evidence around the efficacy of interventions for women experiencing complex situations, stating that "methodological limitations, study quality, and varied outcomes made comparison across studies difficult". Loucks et al. (2006) discuss the "remarkable difficulty" associated with identifying reliable quantitative data to measure the impact of interventions. Fang et al. (2014) identify a lack of knowledge around the impact of gender roles, norms and behaviours on health outcomes from interventions and argue that "much work remains to encourage practitioners to use a gender-sensitive approach when designing interventions".

There was an overall gap in evidence relating to the direct impact of women specific services on children's outcomes. However, we have included a small amount of research and writing around the benefits of improved outcomes for mothers for their children. There is a general consensus that improved outcomes for women, such as their physical and mental health and wellbeing, is beneficial for their children because it creates the conditions for positive childhood outcomes.

The lack of specific evidence around the impact of interventions for women as preventative strategies for child protection is likely to be influenced by the limitations of research methods in this area; it is extremely difficult to determine where harm was prevented as a result of an intervention (i.e. if it would have happened without the intervention). Additionally, it is not possible to isolate the effects of the multiple complex circumstances and interventions often taking place in the lives of people supported by women specific services, therefore limiting the ability of researchers to determine a causal link between an intervention and an outcome, particularly when the outcome relates to a child who was not in direct receipt of the intervention.

It is important to acknowledge the varying needs of women experiencing similar complexities and challenges, which is reflected in the literature presented in this summary. It is also important to emphasise the importance of trans-inclusivity in women specific interventions and that the needs of trans and cisgender women may be different (Lyons et al. 2016). It was not possible to explore this topic specifically within the scope of this Outline, but this is a topic the Iriss ESSS team would be happy to include in a future evidence review.

Accessing resources

We have provided links to the materials referenced in the summary. Some of these materials are published in academic journals and are only available with a subscription through the The Knowledge Network with an NHSScotland OpenAthens username. The Knowledge Network offers accounts to everyone who helps provide health and social care in Scotland in conjunction with the NHS and Scottish Local Authorities, including many in the third and independent sectors. You can register here. Where resources are identified as 'available through document delivery', these have been provided to the original enquirer and may be requested through NHS Scotland's Fetch item service (subject to eligibility).

Where possible we identify where evidence is published open access, which means the author has chosen to publish their work in a way that makes it freely available to the public. Some are identified as author repository copies, manuscripts, or other copies, which means the author has made a version of the otherwise paywalled publication available to the public. Other referenced sources are pdfs and websites that are available publicly.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Dr Cara Jardine at the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research at the University of Strathclyde for expert guidance around relevant research and evidence.

Background

Women specific services are designed to improve outcomes for women. A secondary impact of this may be improved outcomes for children; the rationale being that if effective preventative or treatment services are provided for mothers, their outcomes will be improved, and this will have an impact on children through the benefits derived for the mother, for example preventing imprisonment, improving caring abilities, and protecting children from neglect or abuse. These outcomes relate to thinking around adverse childhood experiences (ACES); childhood adversities include physical/emotional/sexual abuse, mother treated violently, household substance abuse, household member in prison, and emotional and physical neglect.

Nicholles and Whitehead (2012) discuss the indirect benefits of women's community services for children, including around improved maternal wellbeing, reduced maternal offending and reduced maternal substance abuse.

As well as benefiting women directly, the work that women's community services do can also be of benefit to their children and families. There is significant evidence to suggest that improving the well-being of mothers can produce a range of long- term benefits for children. Whilst not every woman attending a women's community service will be caring for children, the long-lasting impact of changes to young people's behaviour and well-being makes this a potentially major area of impact. Improving women's well-being can have a direct impact on outcomes for their children. But other outcomes associated with improved well-being – reduced offending and reduced drug use – can also have knock on impacts on outcomes for children.

The Network of Alcohol and Other Drugs Agencies (2016) discuss the impact of drug and alcohol use on parenting:

Significant maternal drug or alcohol use is associated with a variety of caregiving, child and family functioning problems, including a greater likelihood of neglect or abuse of children, reduced emotional involvement and attachment, increased punitive behaviour toward children, insensitive and interfering behaviour, ambivalent feelings about retaining custody, feelings of guilt and increased parenting stress.

They argue that "organisation level engagement with interventions that serve the needs of women have far-reaching benefits", including "raising awareness regarding the needs of children" in relation to the drug and alcohol treatment of their mothers (Network of Alcohol and Other Drugs Agencies 2016).

To improve outcomes for mothers and, where relevant, their children, women specific services have been developed to address disadvantage. Holly (2017a) identifies five areas of disadvantage faced by women:

- Contact with the criminal justice system

- Homelessness

- Sexual exploitation

- Mental health problems

- Drug and/or alcohol problems

This definition also extends to wider forms of violence against women, encompassing sexual violence, intimate partner violence (IPV), 'honour based' violence, trafficking and female genital mutilation (Holly 2017a). The kinds of interventions provided for women typically include:

- Assigned keyworker and individual casework

- Drug and alcohol cessation treatment

- Provision of information about and access to a range of services relating to health, social care, housing, welfare rights and immigration

- Support around parenting and social service involvement, including provision of childcare

- Individual and group counselling, including those which address trauma, substance use and mental health in an integrated way

- Group work to address issues of self-esteem, confidence and assertiveness

- Ongoing support and aftercare

- Structured activities to reduce social isolation

- Opportunities to undertake education and training, including voluntary work

Need for women's services

Research indicates that in many social contexts, women's outcomes are worse than men's. For example, Karoll and Memmot (2001) identify "clear gender differences with regard to the sequence and frequency of alcohol-related life experiences". Evidence suggests that women with substance use disorders are less likely than their male counterparts to enter treatment over their lifetime (Greenfield et al. 2007). In the context of HIV, women are more likely than men who have sex with men to be undiagnosed or diagnosed late with HIV (Positively UK 2015). WHEC (2011) report that women are more likely to:

- Live with long-term mental health problems

- Be prone to experiencing specific mental health issues

- Experience anxiety disorders

- Be disproportionately affected by post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Suffer from eating disorders

- Self-harm

- Attempt suicide

- Be more vulnerable to HIV infection

Additionally, evidence suggests women experience greater economic hardship than men following divorce (Warrener and Koivunen 2014).

People's outcomes are affected by wider contexts, including personal histories, which are themselves often influenced by previous gendered experiences. For example, women are twice as likely as men to experience interpersonal violence and abuse (Scott and McManus 2016) and to be murdered by their abusive partner. They are more likely to experience trafficking, sex working, sexual abuse and childhood sexual exploitation, and female genital mutilation (Women Centred Working 2016).

These issues can affect outcomes across the life course. In relation to offending, women are significantly more likely than cis-male offenders to have mental health and emotional challenges and experience of domestic violence and sexual abuse, as well as underlying offending often being related to abusive relationships (Nicholles and Whitehead 2012). Women are also more likely to be the main carers for children and to access acute crisis intervention (Women Centred Working 2016). Greenfield et al. (2007) discuss how gendered social inequality influences substance misuse outcomes:

There is evidence that economic disparities, lower educational attainment, and fewer social supports among women compared to men influence access to substance abuse treatment and treatment entry.

The results of their literature review of substance misuse treatment finds a number of patient characteristics that vary by gender, and which relate to treatment outcomes:

[T]reatment outcome may be affected by socioeconomic characteristics (e.g., educational attainment, employment, dependent children), co-occurring psychiatric disorders, history of victimization (e.g., sexual and physical assault in childhood and/or adulthood), type of services used and number of hours in treatment, relapse patterns, and therapist-patient gender matching. Each of these patient- or service-level characteristics varies by gender and can therefore be seen as potentially modifiable gender-specific predictors of treatment outcomes.

Williamson (2013) describes the "ongoing struggle of homeless women to survive the impact of traumatic (and often gender-related) life events". These include "childhood abuse, mental health problems, domestic or sexual violence, drug or alcohol dependencies, sex work and involvement with the criminal justice system" (Williamson 2013). Holly (2017b) describes how these experiences differ by gender:

Women's and men's experiences of multiple disadvantage are significantly different. Women facing homelessness, substance misuse and contact with the criminal justice system are more likely to have experiences of abuse, violence and trauma and particularly poor mental health.

Defining complex needs

NICE (2010) define complex social factors as including domestic abuse, youth, recent migration and substance misuse. In a health context, these characteristics may, for example, be barriers to antenatal care service use because of an increased likelihood of discomfort, embarrassment, limited independence, language and communication challenges, unfamiliarity, coercive control, anxiety and confusion. Other complex social factors not identified by NICE (2010) include physical disability (Thiara 2011), learning disability/cognitive impairment, mental health problems, personality difficulties (Maltman and Turner 2017) homelessness (Cameron et al. 2016), and experience of direct combat (Beder et al. 2011).

These interwoven challenges discussed above and in the previous section can be understood as 'compound oppressions' (Nixon 2009) which create complexity in needs and interventions. In the context of domestic violence, Haeseler (2013) argues that "women of domestic violence abuse require such multifaceted complex care due to the interwoven issues familial abuse brings".

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2004) describes the interwoven nature of problems for women relating to substance misuse:

More often than men, women have been introduced to substances and continue to use substances with their spouses or partners, who may also be physically or sexually abusive. With little emotional support, or financial resources to pay for treatment, childcare or transportation, women find it difficult to enter and remain in treatment. Women also have more severe problems at treatment entry than men. Many have experienced trauma and use substances to cope with these experiences. They are more likely to have mental health problems such as anxiety or depression or post-traumatic stress disorder than men. They also have fewer resources in terms of education, employment and finances.

In relation to disability, Thiara et al. (2011) describe how disabled women who leave violence are likely to have more complex needs, for example accessible accommodation, transport, assistance with personal care, sign language interpreters, or specialised emotional support.

Women specific services

Women specific services generally have two distinct characteristics: they aim to create an appropriate physical space and have distinct ways of working (Nicholles and Whitehead 2012). Effectively designed women's services may lead to improved outcomes in comparison to generic services, with women expressing a preference for women-only spaces (Holly 2017).

It is important to acknowledge that women have different needs in different contexts and to each other. For example in reference to homeless women's services, Haahtela (2013) writes:

[T]here is no single way women experience a service constructed for them and there is no single perspective for organising a service that would suit them.

However, there is evidence to suggest that services designed to meet the specific needs of women can lead to improved outcomes.

Designing services around the needs of women can be practical in nature, for example childcare needs. Although not all women have children, they are more likely to experience childcare needs as a barrier to access than other genders (HM Inspectorate of Probation 2016).

Other aspects of service design and delivery may focus on the specific needs of different women. The Women's Health and Equality Consortium (2011) outlines how the women's health sector can be divided into the following "sub-sectors" to show the range of work undertaken:

- Women's centres that offer a range of health and wellbeing services in a 'one stop shop' approach

- Violence against women and girls (VAWG) organisations which includes those offering services to victims and survivors of domestic and sexual violence

- Organisations working with women offenders and those at risk of offending

- Organisations for Black and Minority Ethnic (BME), refugee and migrant women, many of which also run on a women's centre model, offering a range of services for the local community

- Organisations working around maternal, reproductive and sexual health

In the criminal justice context, women specific services include early intervention and diversion (Prison Reform Trust 2013), including mental health services, support for drug and alcohol misuse, debt counselling, benefits and other financial advice, family support, domestic abuse services, and education, training and employment (HM Inspectorate for Probation).

Evidence

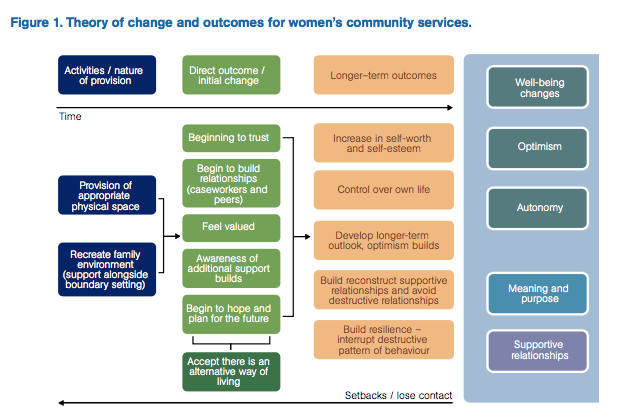

This section presents some key themes around women specific services, and evidence relating to the impact of specific interventions for women with complex needs. Nicholles and Whitehead (2012) outline these outcomes. They present a theory of change illustrating a hypothesised causal relationship:

The following sections discuss evidence of interventions that may connect to aspects presented in the above diagram, and explore evidence that uses one method for demonstrating impact (social return on investment). The final section provides an outline of three potentially useful sources of recommendations for good practice.

Approaches to provision

Trauma-informed services

Trauma is broadly defined as "any event that overwhelms a person's capacity for positive coping" and the five core values of trauma-informed care are based on knowledge of common responses to physical, sexual and emotional abuse (Covington 2016). These values are:

- Safety, both physical and emotional

- Trustworthiness, such as clear expectations and appropriate boundaries

- Choice, prioritisation of women's preferences

- Collaboration, input from women considered in practices and decisions

- Empowerment, recognising strengths and building skills

These values are supported by findings from a qualitative study looking at trauma-informed residential treatment for women conducted by Tompkins and Neale (2018). They found that service delivery was affected by:

- Recruiting and retaining a stable and trained staff team

- Developing therapeutic relationships and working with clients

- Creating and maintaining a safe and stable residential treatment environment

The findings also indicate that both client needs and the demands of trauma-informed treatment are great, and that expectations of 'whole person recovery' are likely to be unrealistic after a single short episode of treatment following a long life history of trauma and abuse. Therefore, it may be better to aim for modest positive changes in clients' life circumstances, improved psychosocial functioning and increased wellbeing and stability. The authors are not stating that 'full recovery' is not possible or that it should not be an aspiration, rather that it is not the only, or necessarily the optimal, measure for evaluating trauma-informed working.

Warshaw and Sullivan (2013) conducted a systematic review of trauma-focused interventions for domestic violence survivors and found these treatments hold promise for reducing mental health symptoms over time. The interventions differed from each other in important ways, such as group versus individual settings, number of sessions offered, content and inclusion criteria, making it difficult to determine if there are specific components that are beneficial for participants. The review also found that safety issues were directly linked to mental health symptoms, and emphasised the importance of collaboration between service providers.

Gender-responsive services

Providing a gender-responsive service involves intentionally creating a safe environment for women through site selection and staff recruitment, as well as developing programmes, content and material that reflects an understanding of the lives of women and girls, and responds to their strengths and challenges (Covington 2016). Six guiding principles for developing women's services are identified by Bloom et al. (2003) as:

- Gender: acknowledge that gender makes a difference

- Environment: create an environment based on safety, respect and dignity

- Relationships: develop policies and practices that are relational promote healthy connections to children, family, significant others and the community

- Services: address substance abuse, trauma, mental health issues in a comprehensive, culturally relevant way

- Socio-economic status: provide opportunities to improve socioeconomic conditions

- Community: establish comprehensive and collaborative community services

In their review of psychosocial interventions targeted towards individuals with specific needs, Mandal and Dhawan (2018) found that women face various systemic, structural, social and individual barriers in treatment seeking and retention for substance abuse, resulting in a drive for gender-sensitive programmes. They state that gender-sensitive interventions of varying intensity have been implemented in various settings, such as outpatient and residential, and in general, the women-only treatment settings reported better treatment utilisation, and greater benefit for women with special needs. Programmes with provision of childcare also had better rates of treatment retention.

Greenfield et al. (2007) found that gender-specific treatment programming and interventions have been demonstrated to enhance treatment entry, retention, and outcomes among only certain subgroups of women with substance use disorders. A number of specific interventions focused on subgroups of women with substance use disorders have demonstrated feasibility and in some instances efficacy. However, these studies have often had small samples or have not yet benefited from a randomized controlled trial of the intervention and additional research is needed to help design effective substance abuse treatment interventions for subgroups of women.

Women specific services

Domestic abuse

Austin et al. (2017) conducted a systematic review of interventions for women parenting in the context of intimate partner violence (IPV). They found that while the effects of IPV for women's parenting is unclear, there is an increasing number of interventions that target aspects of parenting behaviours or outcomes. Common intervention approaches and themes included: providing social support for mothers; improving the mother–child relationship and mother–child interactions; enhancing parenting knowledge and skills; and developing problem-solving skills. This review found tremendous diversity in terms of intervention content and delivery, likely reflecting the complexities of the lives of families affected by IPV, and that the current research base does not yet clearly indicate what interventions or intervention components are most effective for meeting the needs of women parenting in the context of IPV.

In their review of three specific intervention programmes for female victims and survivors of domestic abuse in the UK, Williamson and Abrahams (2014) found there has been little debate about the aims and objectives of these programmes or consideration of their effectiveness. While the structure of these interventions differ considerably, varying from open, rolling courses to closed, time-limited programmes, their primary aims were consistent: to increase women's capacity to recognise the signs of abuse and increase their ability to challenge it. Despite evaluations of the programmes appearing to be successful, little information is provided on how success is being defined and by whom, and the review raises concerns that the interventions are based on an education model that identifies female victims as the problem, taking the focus away from the responsibility of the perpetrator.

Community justice

A national evaluation conducted by Dryden and Souness (2015) examined how 16 women's community justice services (WCJSs) were implemented and to what extent they contributed towards positive outcomes for women. Women often entered WCJS with multiple and complex needs, such has poor mental health, lack of purposeful activities, substance misuse, difficulties in solving everyday problems and unstable or unsupportive family relationships. The importance of holistic support for women was identified in this evaluation, with the co-location or links with multidisciplinary professionals in many WCJSs enabling women to access practical support for multiple issues in one place. Other features commonly identified as being important were:

- Women-only premises, based outside CJSW premises where possible

- Supportive relationships and environments that enable women to connect with workers and other women

- Practitioners with qualities valued by women, such as willingness to listen, non-judgemental, optimistic about women's potential for change, and available for emotional support

- Practical help to overcome barriers often experience by women with complex needs, such as flexible appointments and follow-up

- Sequenced support, which prioritises stability, readiness to change and immediate needs before progressing to longer term outcomes

- A relational, strengths-based approach

A similar evaluation of six third sector services for women offenders in the community in England and Wales also found the value of providing holistic services in women-only settings, particularly for those who have suffered sexual and physical violence (Radcliffe and Hunter 2013). This review found that while these services face considerable pressure to provide evidence of impact, there has been limited investment into systems of outcome measurement, and suggest the development of a single, central monitoring system specifically tailored for women's community services.

Drugs/alcohol/smoking

Grace (2017) reviewed the evidence looking at interventions for drug using women offenders and found the following treatments are currently in use: psychosocial interventions; opiate substitution therapy; therapeutic communities; drug courts; specialist approaches in probation, parole, community supervision and aftercare; self help, peer support and mentoring; and gender-responsive programmes. The findings suggest that programmes specifically designed for women are better at addressing a history of trauma and mental health issues in combination with substance misuse. This review also highlights that interventions need to be appropriate to an individual woman's needs and emphasises the importance of comprehensive aftercare in the community. However, there is also a risk that gender-responsive interventions over-emphasise individual responsibility whilst ignoring structural disadvantages and adverse circumstances.

McHugh et al. (2012) reviewed the literature examining characteristics associated with treatment outcome in adult women where substance use disorders (including alcohol but excluding nicotine) are primary (e.g. not secondary to HIV). The authors found that "once in treatment...gender is not a significant predictor of treatment retention, completion, or outcome". However, they also identified the existence of "gender-specific predictors of outcome" and argue that "individual characteristics and treatment approaches can differentially affect outcomes by gender". Specifically, although the literature indicates that women-only treatment is not necessarily more effective than mixed-gender treatment, service design that focuses on the specific needs of service users achieves better outcomes, and therefore argue that focusing on the needs of specific subgroups is important for efficacy:

[S]ome greater effectiveness has been demonstrated by treatments that address problems more common to substance-abusing women or that are designed for specific subgroups of this population. There is a need to develop and test effective treatments for specific subgroups such as older women with substance use disorders, as well as those with co-occurring substance use and psychiatric disorders such as eating disorders.

Najavits et al. (2018) conducted a randomized controlled trial of a gender-focused addiction model versus a 12-step facilitation for women veterans. They found that substance use generally decreased over time. They conclude that the gender-specific service "provides a useful addition to women's [substance use disorder] treatment options, with outcomes no different than an established evidence-based non-gender-specific model.

Torchalla et al.'s (2012) systematic review of the efficacy of gender-specific smoking cessation programmes including approaches such as such as addressing weight concerns and non-pharmacological aspects of smoking, teaching mood/stress management strategies, scheduling quit dates to be timed to the menstrual cycle, peer counseling, telephone counseling, and gendered information material. The authors found that women-specific tobacco programs help women stop smoking but have similar abstinence rates as non-sex/gender specific programs. However, the authors suggest that offering interventions for women specifically may "reduce barriers to treatment entry and better meet individual preferences of smokers".

Outcomes of women specific services

WHEC (2011) report several outcomes of women specific health services:

- Reducing the number of acute episodes of hospital care

- Reducing depression and anxiety

- Improving self-management of mental and physical health conditions (such as HIV), as well as substance misuse and eating disorders

- Reducing isolation and the deteriorating physical and mental health with which that is associated

They identify several benefits of women specific services that meet the priorities of health and social care providers:

- Responsive to the changing needs of their local populations

- Improves local mental health services

- Saves money

- Specific focus on prevention and early intervention work

- Building links between better health outcomes and employment, especially for people with long-term physical and mental health conditions

Conditions for impact

WHEC (2011) hypothesise several reasons for positive outcomes of women specific health services:

- More Than One Thing ('holistic')

- Service-user led – experts by experience

- Continuity of service provision

- Local knowledge

- Independence, trust and access

Evaluation of some women specific services suggests that the women-specific nature of the services leads to better outcomes because of the women-only nature of the service. For example:

Outcomes Star data has shown that women with complex needs are more likely to make positive change when in women only accommodation than in mixed provision. Overall in complex needs projects, 52% of women in women only projects experienced positive change, compared to 48% in mixed, in spite of the fact that more women in women only projects started at an earlier stage of recovery. The differences are particularly stark in the mental wellbeing and offending scales. (St Mungo's Broadway 2015)

The Prison Reform Trust (2013) argues that criminal justice services and interventions must be 'gender-responsive' in order to work for women. Gender-responsive practice can be divided into five parts:

- Relational - recognising that women develop self-worth through their relationships with others and are motivated by their connections with other people

- Strengths-based - using each woman's individual strengths to develop empowered decisions

- Trauma-informed - recognising the ways in which histories of trauma and abuse impact upon a woman's involvement in the criminal justice system

- Holistic - providing a comprehensive model that addresses the multiple and complex needs of women offenders

- Culturally-informed - services recognise and respond to the diverse cultural backgrounds of women offenders.

HM Inspectorate of Probation (2016) suggest in their report on their inspection of the provision and quality of services in the community for women who offend, that women's centres work best where "women have access to a range of specialist services through a 'one-stop-shop' approach". They report the efficacy of interventions "aimed at addressing the women's needs as a whole, rather than offending behaviour in isolation" and suggest that effective partnership working of relevant agencies can result in the provision of individualised plans and support for women.

Social return on investment

A number of reports refer to the cost benefits of women specific services. For example, Nicholles and Whitehead (2012) argue:

By helping women to make positive changes their lives, women's community services can help reduce demands on state services including police, courts and offender management, prisons and social services, primary and emergency healthcare, and housing.

The most common method of quantifying the economic benefit of women specific service provision we identified in the literature is social return on investment (SROI):

SROI is a method for measuring and reporting on the social, environmental and economic value created by an activity or intervention. SROI builds on and challenges traditional financial and economic tools, such as cost–benefit analysis, and seeks to measure and value the key changes, or outcomes, created by a programme or activity. It not only looks at the economic or financial value, but the social value too, therefore giving a truer reflection of the value created Women's Resource Centre (2011).

The Women's Resource Centre (2011) argues that SROI is a suitable tool for identifying the benefits of women's organisations because of the nature of the outcomes of women specific interventions. This may be because these outcomes are typically difficult to quantify, such as improved mental health and wellbeing, and some are preventative in nature, such as avoidance of children being taken into care.

SROI of women specific services

Women's Resource Centre's (2011) SROI analysis for 5 women's organisations found that:

- For every £1 of investment in services, the social value created by women's organisations ranges between £5 and £11

- The total social value created by women's organisations and specific services within organisations ranges between £1,773,429 and £5,294,226

Additionally, the organisation reports that "[g]rant-holders estimated savings of £1.62m based on a reduced demand on health services, housing and reoffending as a result of preventative intervention" and that "[e]very £1 invested in support-focused alternatives to prison generates £14 worth of social value over ten years." (Women Centred Working 2014)

Health Scotland (2014) undertook an evidence review of the impact of antenatal care services for women with complex social factors such as women who misuse substances, women under the age of 20, and women experiencing domestic abuse, including consideration of the cost effectiveness of specialist service interventions to improve access and uptake of antenatal care. They suggest that early booking, maintained contact and facilitating disclosure of abuse can improve health outcomes such as the number of preterm births, neonatal deaths and maternal mortality.

Grantees of the Women's Diversionary Fund (Nicholles and Whitehead 2012) that supports interventions around diversion, prevention and reducing reoffending for vulnerable women and women at risk of offending, estimate that across their client group they have been responsible for £1,620,000 in savings based on a reduced demand across the areas of health, reoffending and housing:

- Health: A&E admissions, NHS mental health service usage, drug and alcohol treatment (£230,000 value reduction in service usage)

- Criminal justice: arrest, court appearances, custodial sentences, breaching hearings (£630,000 value reduction in service usage)

- Housing: avoidance of eviction, number of women maintaining stable accommodation (£760,000 value reduction in service usage)

Among the five grantees, the SROI analyses found that their services returned a social value of between £3.44 and £6.65 for every £1 invested.

Women Centred Working (2014) argue that the cost of community based services for women with complex needs is low in comparison to sentencing:

National Offender Management Service figures priced a prison place at £49k per woman per year and a community order at £2,800. When compared with the estimated projected cost of holistic community based services, which averages at £1,300 per woman, this is a substantial saving.

In their evaluation of the 218 service for women offenders, Loucks et al. (2006) suggest that "engaging women with services is likely to deliver a range of economic savings" related to reduced drug use and offending behaviour, and that further benefits can be drawn from retaining individuals in treatment. They also emphasise, however, the need to consider the cost-benefits of preventative health care alongside several unquantifiable benefits of women specific offending services (such as improvements in appearance, coping ability and self-esteem).

Guidelines for good practice

The following resources may be useful for service providers seeking to implement good practice approaches. We identified them as outlining particularly clear approaches, but the resources discussed in the rest of this Outline are also likely to contain useful material in terms of methodology for design and evaluation and meeting the needs of diverse and complex user bases.

Holly, J (2017) Mapping the maze: services for women experiencing multiple disadvantage in England and Wales. Agenda and AVA (pdf)

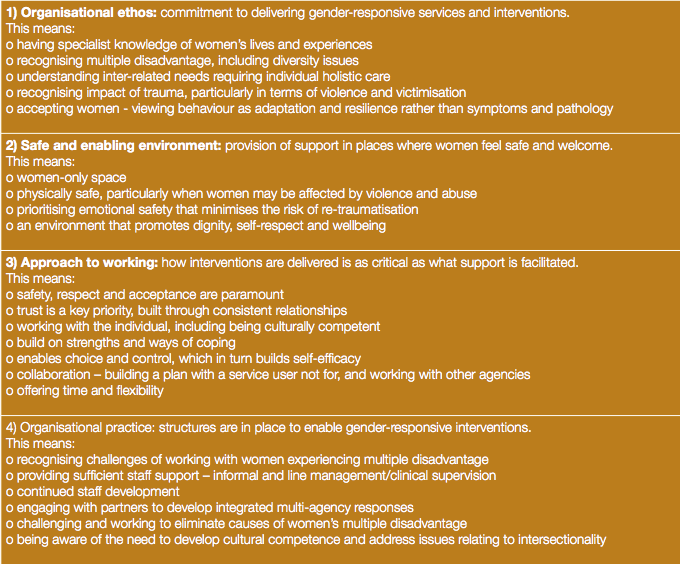

As part of the Mapping the Maze project in England and Wales, Holly developed a model of good practice for working with women affected by substance use, mental ill-health, homelessness and offending. This model was developed by conducting a literature review, consultation with previous service users and professionals, and campaigners. Recommendations for service providers include specific actions under the themes:

- Adopt the Mapping the Maze model

- Create a trauma-informed culture

- Commit to providing holistic women-only support

- Build strong partnerships

- Speak to women directly

The Mapping the Maze model integrates "the gender-responsive and trauma-informed approaches to service delivery...identified in the literature review and tested in the consultation with women with lived experience, and that of relevant professionals". The model has four broad components: organisational ethos, safe and enabling environment, approach to working and organisational practice.

National Drug & Alcohol Research Centre (2013) It's time to have the conversation: understanding the treatment needs of women who are pregnant and alcohol dependent (website)

This report presents a narrative literature review of treatments available to pregnant women who have alcohol use disorders and findings from interviews with key stakeholders regarding current treatment practices and areas requiring improvement.

Network of Alcohol and Other Drugs Agencies (2016) Working with women engaged in alcohol and other drug treatment (pdf)

The purpose of the resource is to raise the profile of women in AOD treatment. Improving service provision to women means acknowledging their unique experiences and perspectives, enhancing the best practice approaches AOD treatment services already have in place and/or adopting philosophical perspectives that give a greater voice to the needs of women. Organisation level engagement with interventions that serve the needs of women have far-reaching benefits. These include improving gender responsiveness, addressing issues related to family violence for both victims and perpetrators, raising awareness regarding the needs of children and introducing concepts around positive parenting and family inclusive practice.

This resource provides structural solutions, such as building sustainable community partnerships, professional development and worker self-care that are essential in supporting improved work practices with women. Developed from evidence-based practice and research, this resource has brought together relevant findings from the literature and practice experience as a starting point for deeper consideration and discussion into the needs of women accessing AOD treatment.

References

Austin, AE et al. (2017) A systematic review of interventions for women parenting in the context of intimate partner violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, pp.1-22 (paywalled)

Beder, J et al. (2011) Women and men who have served in Afghanistan/Iraq: coming home. Social Work in Health Care, 50(7), pp.515–526 (paywalled)

Bloom, BE (2015) Meeting the needs of women in california's county justice system: a toolkit for policymakers and practitioners, pp.1–28 (open access)

Cameron, A et al. (2016) From pillar to post: homeless women's experiences of social care. Health and Social Care in the Community, 24(3), pp.345–352 (paywalled or author manuscript)

Covington, S (2016) Becoming trauma informed toolkit for women's community service providers (pdf)

Dryden, R and Souness, C (2015) Evaluation of sixteen women's community justice services in Scotland. Scottish Government and IRISS (pdf)

Fang, ML et al. (2014) Exploring promising gender-sensitive tobacco and alcohol use interventions: results of a scoping review. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(11), pp.1400–1416 (paywalled or author copy)

Grace, S (2017) Effective interventions for drug using women offenders: a narrative literature review. Journal of Substance Use, 22(6), pp.664–671 (paywalled or author repository copy)

Greenfield, SF et al. (2012) Substance abuse treatment: entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86(1), pp.1–21 (open access)

Haahtela, R (2014) Homeless women's interpretations of women-specific social work among the homeless people. Nordic Social Work Research. Routledge, 4(1), pp.5–21 (paywalled)

Haeseler, LA (2013) Organizational development structure: improvements for service agencies aiding women of abuse. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 10(1), pp.19–24 (paywalled)

HM Inspectorate of Probation (2016) A thematic inspection of the provision and quality of services in the community for women who offend (pdf)

Holly, J (2017a) The core components of a gender sensitive service for women experiencing multiple disadvantage: a review of the literature. AVA and Agenda (pdf)

Holly, J (2017b) Mapping the maze: services for women experiencing multiple disadvantage in England and Wales. Agenda and AVA (pdf)

Karoll, BR and Memmott, J (2001) The order of alcohol-related life experiences. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 1(2), pp.45–60 (paywalled)

Krahn, J et al. (2018) Housing interventions for homeless, pregnant/parenting women with addictions: a systematic review. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 27(1), pp.75–88 (paywalled)

Loucks, N et al. (2006) Evaluation of the 218 Centre. Scottish Government (website)

Lyons, T et al. (2016) Experiences of trans women and two-spirit persons accessing women-specific health and housing services in a downtown neighborhood of Vancouver, Canada. LGBT Health, 3(5), pp.373–378 (paywalled or author copy)

Maltman, LJ and Turner, EL (2017) Women at the centre – using formulation to enhance partnership-working: a case study. The Journal of Forensic Practice, 19(4), pp.278–287 (paywalled)

Mandal, P and Dhawan, A (2018) Interventions in individuals with specific needs. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 60(4), pp.S553–S558 (open access)

McHugh, RK et al. (2012) Substance abuse treatment entry, retention and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86(1), pp.1–21 (open access)

Najavits, LM et al. (2018) A randomized controlled trial of a gender-focused addiction model versus 12-step facilitation for women veterans. American Journal on Addictions, 27(3), pp.210–216 (paywalled)

National Drug & Alcohol Research Centre (2013) It's time to have the conversation: understanding the treatment needs of women who are pregnant and alcohol dependent (website)

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2010) Pregnancy and complex pregnancy and complex social factors: a model for service provision for pregnant women with complex social factors (website)

Network of Alcohol and Other Drugs Agencies (2016) Working with women engaged in alcohol and other drug treatment (pdf)

Nicholles, N and Whitehead, S (2012) Women's community services: a wise commission (pdf)

Nixon, J (2009) Domestic violence and women with disabilities: locating the issue on the periphery of social movements. Disability & Society, 24(1), pp.77–89 (paywalled)

Positively UK (2015) Women know best: what are the best practices in effective, high quality HIV support for women in the UK? (pdf)

Prison Reform Trust (2013) International good practice: alternatives to imprisonment for women offenders (pdf)

Radcliffe, P et al. (2013) The development and impact of community services for women offenders: an evaluation (pdf)

Scott, S and McManus, S (2016) Hidden hurt: violence, abuse and disadvantage in the lives of women. DMSS Research for AGENDA (pdf)

St. Mungo's Broadway (2015) Rebuilding shattered lives: the final report (pdf)

Thiara, RK et al. (2011) Losing out on both counts: disabled women and domestic violence. Disability & Society, 26(6), pp.757–771 (paywalled)

Tompkins, CNE and Neale, J (2018) Delivering trauma-informed treatment in a women-only residential rehabilitation service: qualitative study, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 25(1), pp.47–55 (paywalled)

Torchalla, I et al. (2012) Smoking cessation programs targeted to women: a systematic review. Women & Health, 52(1), pp.32-54 (paywalled)

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2004) Substance abuse treatment and care for women: case studies and lessons learned (pdf)

Warshaw, C et al. (2013) A systematic review of trauma-focused interventions for domestic violence survivors. National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health (pdf)

Williamson, E et al. (2013) The TARA project: a longitudinal study of the service needs of homeless women. NIHR School for Social Care Research (pdf)

Women Centred Working (2014) Showcasing women centred solutions (pdf)

Women Centred Working (2016) Taking forward women centred solutions (pdf)

Women's Health and Equality Consortium (2011) Value of the women's voluntary and community sector delivering health services (pdf)

Women's Resource Centre (no date) Women only services (website)